One religion is as true as another.

—Robert Burton, 1621

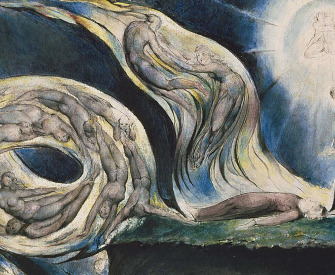

Christ in the Wilderness, by Moretto da Brescia, c. 1515–20. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund, 1911.

What preoccupies us, then, is not God as a fact of nature, but as a fabrication useful for a God-fearing society. God himself becomes not a power but an image.

—Daniel J. Boorstin

This issue of Lapham’s Quarterly doesn’t trade in divine revelation, engage in theological dispute, or doubt the existence of God. What is of interest are the ways in which religious belief gives birth to historical event, makes law and prayer and politics, accounts for the death of an army or the life of a saint. Questions about the nature or substance of deity, whether it divides into three parts or seven, speaks Latin to the Romans, in tongues when traveling in Kentucky, I’ve learned over the last sixty-odd years to leave to sources more reliably informed. My grasp of metaphysics is as imperfect as my knowledge of Aramaic. I came to my early acquaintance with the Bible in company with my first readings of Grimm’s Fairy Tales and Bulfinch’s Mythology, but as an unbaptized child raised in a family unaffiliated with the teachings of a church, I missed the explanation as to why the stories about Moses and Jesus were to be taken as true while those about Apollo and Rumpelstiltskin were not.

Satan devouring the damned, from Last Judgment (detail), by Fra Angelico, c. 1432–35. Museo di San Marco, Florence, Italy.

Four years at Yale College in the 1950s rendered the question moot. It wasn’t that I’d missed the explanation; there was no explanation to miss, at least not one accessible by means other than the proverbial leap of faith. Then as now, the college was heavily invested in the proceeds of the Protestant Reformation, the testimony of God’s will being done present in the stonework of Harkness Tower and the cautionary ringing of its bells, as well as in the readings from scripture in Battell Chapel and the petitionings of Providence prior to the Harvard game. The college had been established in 1701 to bring a great light unto the gentiles in the Connecticut wilderness, the mission still extant 250 years later in the assigned study of

Jonathan Edwards’ sermons and John Donne’s verse. Nowhere in the texts did I see anything other than words on paper—very beautiful words but not the living presence to which they alluded in rhyme royal and iambic pentameter. I attributed the failure to the weakness of my imagination and my poor performance at both the pole vault and the long jump.

I brought the same qualities into the apostate lecture halls where it was announced that God was dead. The time and cause of death were variously given in sophomore and senior surveys of western civilization—disemboweled by Machiavelli in sixteenth-century Florence, assassinated in eighteenth-century Paris by agents of the French Enlightenment, lost at sea in 1835 while on a voyage with Charles Darwin to the Galapagos Islands, garroted by Friedrich Nietzsche on a Swiss Alp in the autumn of 1882, disappeared into the nuclear cloud ascending from Hiroshima on August 6, 1945. The assisting coroners attached to one or another of the history faculties submitted densely footnoted autopsy reports, but none of the lab work brought forth a thumbprint of the deceased.

The fact of God’s life apparently as unverifiable as the proof of his death, I reached the conclusion suggested by the French philosopher Michel Onfray that “God is neither dead nor dying because he is not mortal”—the story about the blessed Virgin in the manger with the three Magi therefore made of the same cloud-capped stuff as the story about Goldilocks in the forest with the three bears. Onfray observes that “a fiction does not die, an illusion never passes away,” situating Yahweh, together with Ulysses, Allah, Lancelot of the Lake, and Gitche Manitou, among the immortals sustained on the life-support systems of poetry and the high approval ratings awarded to magicians pulling rabbits out of hats. Similarly the British essayist William Hazlitt, who likens the fabrication of divinity to a little girl’s dressing up her favorite doll, a harmless enough occupation until the dolls, turning “deformed and preposterous,” prompt their votaries to drench “the earth with tears and blood.”

The conclave of historians in New Haven placed a strong emphasis on the tears and blood, posting on a blackboard or a map the long list of religious wars, inquisitions, crusades, massacres, and persecutions visited upon the unfaithful by, among others, Richard the Lionheart, Savonarola, Arnaud Amalric, Philip II, Suleiman the Magnificent, Oliver Cromwell, and Vlad the Impaler. Fortunately, so it was said on the lawn of the Elizabethan Club, the revels now were ended, the dungeons and the burnings at the stake shipped off in disgrace to the land of once upon a time. The authors of the American Constitution had seen fit to separate the ambition of the church from the avarice of the state, with the happy result that God’s awful and majestic wrath had been securely housed within the walls of the Yale Art Gallery, restricted to the Christmas performance of Handel’s Messiah in Woolsey Hall.

The Sacred Grove, by Arnold Böcklin, 1882. Kunsthalle Hamburg, Germany.

The good news brought with it what Warren Breckman names as “a master narrative” of mid-twentieth-century American social science, the one that reduces God from a power to an image and makes secularization “virtually synonymous with modernization.” It wasn’t that the twentieth century had lost either the talent or the taste for the projects of mass murder—the autos-da-fé staged by Joseph Stalin, Mao Zedong, and Adolf Hitler on a scale undreamed of in the theology of Pope Innocent IV—but the miraculous births of Fat Man and Little Boy in the cradle at Los Alamos had placed the fire of heaven under the control of the secular authorities, into the hands of wise scientists and caring statesmen. What had been divine had become human, the hydrogen bomb revealed as both symbol and freight-forwarding agent for the Day of Judgment.

Religion hadn’t lost its capacity to bestow, again according to Breckman, “the consoling message of cosmic meaning and personal redemption,” to comfort countless numbers of its adherents afraid of death and acquainted with grief, to illuminate the masterpieces of Chartres Cathedral and the Mass in B Minor, to introduce Gerard Manley Hopkins to the power and glory of “chestnut-falls and finches’ wings,” to restore in Leo Tolstoy “the joy of being,” but it had been relieved of its character as a public menace. Henceforth religion was to be understood as a private good, available in cloaks of many colors; it no longer had anything to do with the day-to-day operations of a world subject to the laws of physics and the rule of reason.

drop_cap]Thus reassured, the students of my generation and disposition were free to set foot in Sodom without fear of divine vengeance. The license to dance to the music of the 1960s sexual revolution, to know ourselves “self-begot, self-raised” in the manner of John Milton’s Satan, didn’t negate the 1952 Supreme Court majority opinion that the Americans “are a religious people whose institutions presuppose a Supreme Being.” Nor did it cancel my membership in the God-fearing society established on the Biblical foundations of John Winthrop’s seventeenth-century city upon a hill. In the way that Montaigne knew himself to be a Christian “by the same title that we are Perigordians or Germans,” I was Christian, maybe unbaptized and without the documents required to clear customs in Paradise, but Christian nonetheless. It didn’t matter whether I believed that on the third day Christ had risen from the dead, or that both God and Cecil B. DeMille had parted the Red Sea to accommodate Moses on the flight from Egypt. The history of that belief had been indelibly sequenced into the strands of my metaphysical DNA, dictating my turns of mind and choices of word, superintending my sense of right and wrong, accounting for my fears of women and the stock market.

The whole fabric of the American creation is woven with threads of Christian thought. The language and sanction of the Bible informs the texts of both the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence. The law of the land rests on the premise that crimes are sins, acts of a disobedient free will unbeholden to the early toilet training of the Ten Commandments. The inscription on the Liberty Bell borrows from Leviticus 25 the instruction given by God to Moses on Mount Sinai: “Proclaim liberty throughout all the land unto all the inhabitants thereof”—all the inhabitants understood to be limited (in Philadelphia in 1776 as in Sinai in the thirteenth century BC) to those whom God had chosen as his own—no Negroes or Moabites among them. The country’s codes of moral and social conduct presuppose no known connection between the birdsong of the spirit and the dungheap of the flesh. Any citizen who stands for public office is first expected to pledge allegiance to the Lord of hosts in whom the country trusts to back its currency. Cures for the soul prescribe salutary doses of suffering and guilt. The dominant trait in the national character is the longing for transcendence and the belief in what isn’t there—the promise of the sweet hereafter that sells subprime mortgages in Florida and corporate skyboxes in heaven.

I believe in an America where the separation of church and state is absolute, where no Catholic prelate would tell the president (should he be a Catholic) how to act and no Protestant minister would tell his parishioners for whom to vote.

—John F. Kennedy, 1960Not that I encountered, at least not in New York or Washington or Los Angeles, large numbers of people leading lives in accordance with the Sermon on the Mount. Poolside in Beverly Hills the name of the Lord seldom came up in conversation unless it was being taken in vain. “The hunger and thirst for righteousness” was notably absent from both the character and policy of the Nixon administration. Neither the poor nor the meek were inheriting estates in Westchester County. None of the Las Vegas hotels listed prompt medical attention as one of the finer amenities available to guests disposing of their right hands and plucking out their right eyes.

The wanderings away from the road to Damascus I took to be confirmations of the secular narrative bound up in the diploma from Yale, further proofs during the decade of the 1970s that although the Christian pieties remained securely in place on the pediment of the Supreme Court, on the table with the coffee at White House prayer breakfasts, acknowledged in absentia at Hollywood weddings, the spiritual infrastructure was beginning to show signs of disrepair—if not at the Iowa State Fair, certainly at the cineplex in downtown Des Moines. My travels seldom took me anywhere except to California or Europe, but if sometimes in an airport bar I ran across a third-generation Baptist, I avoided the embarrassment of a conversation about the Second Coming in much the same way that I’d learned to withhold comment when asked by an author for an opinion of his unintelligibly avant-garde off-Broadway play.

By the mid 1980s I understood that I had been making a serious mistake. Jesus had risen from the tomb in Tennessee into which he had been carried by Clarence Darrow in 1925. He was now appearing at political rallies with Jerry Falwell’s Moral Majority, on campus at Bob Jones University to second the motions against abortion, made an honorary member of the National Association of Evangelicals (thirty million exalted souls) that embodied one seventh of the nation’s eligible voters. The resurrected sensibility abroad in the land during the sunshine years of the Reagan administration led to the publication of the Left Behind series of Christian thrillers (sixteen volumes, sixty-five million copies sold), foretelling the marvelous and soon forthcoming day when the saved shall be lifted to heaven and the damned shall writhe in pain. Drawing on the precedents in the Pentateuch, the coauthors of the books, Tim LaHaye and Jerry B. Jenkins, express their love of God by delighting in their hatred of man. They imagine the battle of Armageddon as the wholesale slaughter of apostates in Boston and homosexuals in Brooklyn, “their innards and entrails gushed to the desert floor…their blood pooling and rising in the unforgiving brightness of the glory of Christ.”

The Vision Legend of the Fourteenth Century, by Luc Olivier Merson, c. 1872. Palais des Beaux-Arts de Lille, France.

Increasingly frequent sightings of the great beast of the Book of Revelation in Oklahoma recruited large numbers of congregants similarly ill disposed toward the secularization of America’s elementary schools. Their collective suspicion of all things urban or modern congealed during the 1990s into a political constituency that in 2000 sent to the White House the twice-born George W. Bush. The bringing down of the World Trade Center towers on September 11, 2001, caused him to behold a geopolitical vision (“the monumental struggle of good versus evil”) not unlike the one vouchsafed to Ezekiel in the desert of Judaea. During the rest of his term in office—as bound as had been the prophets of the Old Testament to render justice, mete out punishment, cleanse the world of its impurities—Bush construed the American purpose as surrogate for the will of the Lord. “The liberty we prize is not America’s gift to the world, it is God’s gift to man.” “Events aren’t moved by blind change and chance…but by the hand of a just and faithful God.”

The American president wasn’t alone in his launching of faith-based initiatives. Together with the rising of militant religious fervor in the United States during the last thirty years, devout and literal-minded readings of the Qur’an have brought forth war in Iraq and Afghanistan, massacre in Africa and the Balkans, suicide bombing in Israel, Pakistan, India, and Palestine, heavy security encircling the presence of President Barack Obama, elected to the White House in his persona as a Messiah come not to govern the country but to redeem it.

The flow of tears and blood on the ground has been accompanied by a torrent of theological and quasi-theological polemic slouching toward the postulate of an apocalypse. Treatises tracking The Evolution of God or declaring The End of Faith; tracts forecasting The Clash of Civilizations or arguing that Everything You Know about God Is Wrong; magazine articles, op-ed essays, special broadcasts from CNN and Fox worried, not unreasonably, that the rabbis in Jerusalem might seek a thermonuclear settlement of their doctrinal differences with the mullahs in Tehran.

More than one essay in this issue of Lapham’s Quarterly regards the secularization of the old religious festivals as a fait accompli. The toxic levels of fear and superstition lowering the air quality in the news and entertainment media—in the nominally nondenominational sectors of cyberspace as well as those under ecclesiastical obligation—suggest otherwise. If large provinces of meaning have been lost to the mandate of the three wrathful monotheisms, so also the master narrative of mid-twentieth-century American social science has depleted its resources of relevance and romance.

In both the public and private sectors of the American mind at the turn of the third millennium, the delusional was no longer marginal. Myriad varieties of free-form transcendence were being backed with the assumption that the emotional intensity with which one held to one’s belief, whether in the existence of witches or the extinction of capitalism, validated its credentials—passion perceived as truth in place of truth pursued with passion, no superstition more deserving or more preposterous than any other as long as it was sincere. The methodologies of magical thinking that informed the debates in Congress (about Saddam Hussein’s weapons of mass destruction and the export of democracy to Baghdad and Kabul) were made manifest in the nationwide challenges to the teaching of evolution as well as in the quality of the credit-default swaps sold on Wall Street. Most wonderfully of all, they were revealed in President Bush’s apparent assumption that America could rule a world about which it chooses to know as little as possible.

Expulsion of Albigensian heretics from Carcassonne in 1209 during the Albigensian Crusade, from Les Grandes chroniques de France, c. 1350. British Library, London.

The desperate and always popular demand for news from nowhere bears out Michel Onfray’s supposition that “the last god will expire with the last man,” accords with

Alexis de Tocqueville’s observation that “unbelief is an accident,” faith “the only permanent state of mankind.” Tocqueville relies on his premise that “religion is simply another form of hope…no less natural to the human heart than hope itself,” that as long as it is sustained upon the desire for immortality, “it can only be destroyed by another religion.”

I see no reason to doubt him, and I take it as a task of the twenty-first century to come forward with the fabrication of an image of the divine more closely allied with the strands in the double helix and the structure of the cell, an image that reburies in the desert sand the murderous fiats of Moses and Muhammad and are therefore more useful to societies destined to remain God-fearing. Accept religion as a work of the human imagination (the God made in man’s image one and the same with the man made in God’s image) and the means of creation is not a brooding upon the waters or an engineering of the firmament, but the telling of a story. Both the Old and the New Testaments find their metaphors in the facts on the ground, God likened to a mountain or a lion, his kingdom to a fisherman’s net, a mustard seed, the yeast “hid in three measures of meal.”

Surely we can do likewise; God is the greatest of man’s inventions, and we are an inventive people, shaping the tools that in turn shape us, and we have at hand the technology to tell a new story congruent with the picture of the earth as seen from space instead of the one drawn on the maps available to the prophets wandering the roads of the early Roman Empire. In the field of American literature no growth is more fruitful than the contemplations of nature clothed in the raiment of transcendence. The words have been with us since the beginning, in the writings of J. Hector St. John de Crèvecoeur and President Thomas Jefferson, as well as in those of Ralph Waldo Emerson and President Theodore Roosevelt, who, during the first decade of the twentieth century, placed 230 million acres of the American wilderness into a Federal Witness Protection Program, meaning to preserve “all useful and beautiful wild things” for the generations yet unborn in order that they might come to know that the “sunshine in the upper air” is more beautiful and useful than the light filtered through stained-glass windows, that the sight of birds in the sky at noon is like “a gallery of the masterpieces of the artists of all time.”

God is really only another artist. He invented the giraffe, the elephant, and the cat. He has no real style. He just goes on trying other things.

—Pablo Picasso, 1964Gathered in the mulch of print over the last three hundred years, the American delvings into nature (those of Audubon, Thoreau, Leopold, Muir, Eiseley, Carson, Berry, Dillard, Lopez, Abbey, Hitt, Matthiessen, Erdrich, et al.) can be likened to the compost heap engendering the science and logos of the polytheism (premodern and post-Christian) that discovers every organism in the cosmos to be made from the wreckage of spent stars. The ancient Greeks assigned trace elements of the divine to trees and winds and stones (a river god sulked and the child drowned; the fertility goddess smiled and the corn ripened); the modern American assigns trace elements of the divine to arctic glaciers and tropical rain forests (the ice melts and cities drown; parrots multiply and the flowers bloom.)

A religion still hidden, like the yeast in the three measures of meal, in the secular disguise of environmentalism. The foundational metaphysics already have been incorporated into rituals of devout observance. The worshipful recyclings of eggshells and orange rinds celebrate the resurrection of the disembodied spirit; the eating of free-range chickens and organic heirloom tomatoes signifies the partaking in a feast of communion. Like the Councils of Nicaea and Trent, international conferences addressed to the problem of climate change seek to certify the existence of the Holy Ghost. The miracle is the rabbit, not the pulling of the rabbit out of a hat.