I am a living symbol of the white man’s fear.

—Winnie Mandela, 1985Unwritten Law

Ida B. Wells on lynching.

Our country’s national crime is lynching. It is not the creature of an hour, the sudden outburst of uncontrolled fury, or the unspeakable brutality of an insane mob. It represents the cool, calculating deliberation of intelligent people who openly avow that there is an “unwritten law” that justifies them in putting human beings to death without complaint under oath, without trial by jury, without opportunity to make defense, and without right of appeal.

The “unwritten law” first found excuse with the rough, rugged, and determined man who left the civilized centers of eastern states to seek for quick returns in the gold fields of the far West. Following in uncertain pursuit of continually eluding fortune, they dared the savagery of the Indians, the hardships of mountain travel, and the constant terror of border-state outlaws. Naturally, they felt slight toleration for traitors in their own ranks. It was enough to fight the enemies from without; woe to the foe within! Far removed from and entirely without protection of the courts of civilized life, these fortune seekers made laws to meet their varying emergencies. The thief who stole a horse, the bully who “jumped” a claim, was a common enemy. If caught he was promptly tried, and if found guilty was hanged to the tree under which the court convened.

Those were busy days of busy men. They had no time to give the prisoner a bill of exception or stay of execution. The only way a man had to secure a stay of execution was to behave himself. Judge Lynch was original in methods but exceedingly effective in procedure. He made the charge, impaneled the jurors, and directed the execution. When the court adjourned, the prisoner was dead. Thus lynch law held sway in the far West until civilization spread into the territories and the orderly processes of law took its place. The emergency no longer existing, lynching gradually disappeared from the West.

But the spirit of mob procedure seemed to have fastened itself upon the lawless classes, and the grim process that at first was invoked to declare justice was made the excuse to wreak vengeance and cover crime. It next appeared in the South, where centuries of Anglo-Saxon civilization had made effective all the safeguards of court procedure. No emergency called for lynch law. It asserted its sway in defiance of law and in favor of anarchy. Here it has flourished ever since, marking the thirty years of its existence with the inhuman butchery of more than ten thousand men, women, and children by shooting, drowning, hanging, and burning them alive. Not only this, but so potent is the force of example that the lynching mania has spread throughout the North and Middle West. It is now no uncommon thing to read of lynchings north of Mason and Dixon’s line, and those most responsible for this fashion gleefully point to these instances and assert that the North is no better than the South.

The Vision of Saint John, by El Greco, c. 1609–14. © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund, 1956.

This is the work of the “unwritten law” about which so much is said, and in whose behest butchery is made a pastime and national savagery condoned. The first statute of this “unwritten law” was written in the blood of thousands of brave men who thought that a government that was good enough to create a citizenship was strong enough to protect it. Under the authority of a national law that gave every citizen the right to vote, the newly made citizens chose to exercise their suffrage. But the reign of the national law was short-lived and illusionary. Hardly had the sentences dried upon the statute books before one southern state after another raised the cry against “Negro domination” and proclaimed there was an “unwritten law” that justified any means to resist it.

The method then inaugurated was the outrages by the Red Shirt bands of Louisiana, South Carolina, and other southern states, which were succeeded by the Ku Klux Klan. These advocates of the “unwritten law” boldly avowed their purpose to intimidate, suppress, and nullify the Negro’s right to vote. In support of its plans, the Ku Klux Klan, the Red Shirts, and similar organizations proceeded to beat, exile, and kill Negroes until the purpose of their organization was accomplished and the supremacy of the “unwritten law” was effected. Thus lynchings began in the South, rapidly spreading into the various states until the national law was nullified and the reign of the “unwritten law” was supreme. Men were taken from their homes by Red Shirt bands and stripped, beaten, and exiled; others were assassinated when their political prominence made them obnoxious to their political opponents; while the Ku Klux barbarism of election days, reveling in the butchery of thousands of colored voters, furnished records in congressional investigations that are a disgrace to civilization.

The alleged menace of universal suffrage having been avoided by the absolute suppression of the Negro vote, the spirit of mob murder should have been satisfied and the butchery of Negroes should have ceased. But men, women, and children were the victims of murder by individuals and murder by mobs, just as they had been when killed at the demands of the “unwritten law” to prevent “Negro domination.” Negroes were killed for disputing over terms of contracts with their employers. If a few barns were burned, some colored man was killed to stop it. If a colored man resented the imposition of a white man and the two came to blows, the colored man had to die, either at the hands of the white man then and there or later at the hands of a mob that speedily gathered. If he showed a spirit of courageous manhood, he was hanged for his pains, and the killing was justified by the declaration that he was a “saucy nigger.” Colored women have been murdered because they refused to tell the mobs where relatives could be found for “lynching bees.” Boys of fourteen years have been lynched by white representatives of American civilization. In fact, for all kinds of offenses—and for no offenses—from murders to misdemeanors, men and women are put to death without judge or jury; so that, although the political excuse was no longer necessary, the wholesale murder of human beings went on just the same. A new name was given to the killings, and a new excuse was invented for so doing.

Again the aid of the “unwritten law” is invoked, and again it comes to the rescue. During the last ten years, a new statute has been added to the “unwritten law.” This statute proclaims that for certain crimes or alleged crimes, no Negro shall be allowed a trial; that no white woman shall be compelled to charge an assault under oath or to submit any such charge to the investigation of a court of law. The result is that many men have been put to death whose innocence was afterward established; and today, under this reign of the “unwritten law,” no colored man, no matter what his reputation, is safe from lynching if a white woman, no matter what her standing or motive, cares to charge him with insult or assault.

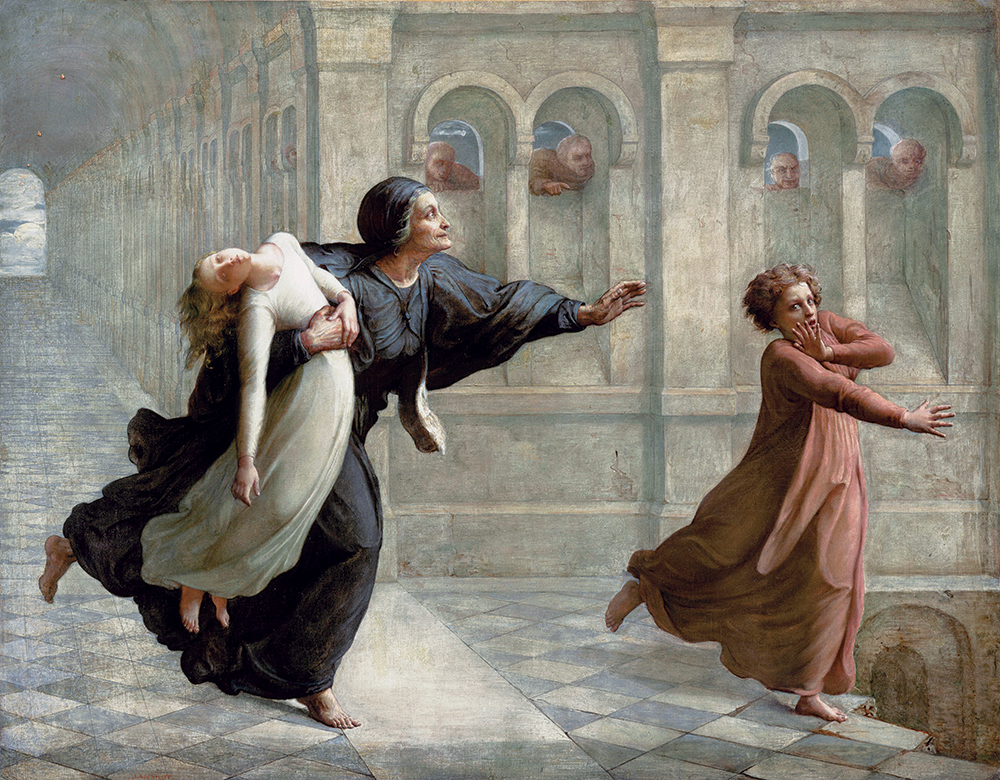

Nightmare, from the painting cycle The Poem of the Soul, by Louis Janmot, 1854. © RMN-Grand Palais / Art Resource, NY.

It is considered a sufficient excuse and reasonable justification to put a prisoner to death under this “unwritten law” for the frequently repeated charge that these lynching horrors are necessary to prevent crimes against women. The sentiment of the country has been appealed to in describing the isolated condition of white families in thickly populated Negro districts; and the charge is made that these homes are in as great danger as if they were surrounded by wild beasts. And the world has accepted this theory without let or hindrance. In many cases there has been open expression that the fate meted out to the victim was only what he deserved. In many other instances, there has been a silence that says more forcibly than words can proclaim it that it is right and proper that a human being should be seized by a mob and burned to death upon the unsworn and the uncorroborated charge of his accuser. No matter that our laws presume every man innocent until he is proved guilty; no matter that it leaves a certain class of individuals completely at the mercy of another class; no matter that it encourages those criminally disposed to blacken their faces and commit any crime in the calendar so long as they can throw suspicion on some Negro, as is frequently done, and then lead a mob to take his life; no matter that mobs make a farce of the law and a mockery of justice; no matter that hundreds of boys are being hardened in crime and schooled in vice by the repetition of such scenes before their eyes—if a white woman declares herself insulted or assaulted, some life must pay the penalty, with all the horrors of the Spanish Inquisition and all the barbarism of the Middle Ages. The world looks on and says it is well.

Ida B. Wells-Barnett

From “Lynch Law in America.” Born a slave in Mississippi in 1862 a few months before the Emancipation Proclamation, Wells began writing for Memphis newspapers in her twenties. In 1892 three black businessmen—among thirty black men arrested in the wake of altercations in a mixed-race neighborhood—were dragged from a Memphis jail and shot. Spurred by the event, Wells began a lifelong antilynching campaign, causing her to receive many death threats and driving her to move from Memphis to Chicago in 1893.