The world began without man, and it will end without him.

—Claude Lévi-Strauss, 1955Remembering the Future

Philip K. Dick’s precogs see the future, but they can’t change it.

Still in gay pinstripe clown-style pajamas, Joe Chip hazily seated himself at his kitchen table, lit a cigarette and, after inserting a dime, twiddled the dial of his recently rented ’pape machine. Having a hangover, he dialed off interplan news, hovered momentarily at domestic news, and then selected gossip.

“Yes sir,” the ’pape machine said heartily. “Gossip. Guess what Stanton Mick, the reclusive, interplanetarily known speculator and financier, is up to at this very moment.” Its works whizzed, and a scroll of printed matter crept from its slot; the ejected roll, a document in four colors, niftily incised with bold type, rolled across the surface of the neoteakwood table and bounced to the floor. His head aching, Chip retrieved it, spread it out flat before him.

Mick Hits World Bank for Two Tril (AP) London. What could Stanton Mick, the reclusive, interplanetarily known speculator and financier be up to? the business community asked itself as rumor leaked out of Whitehall that the dashing but peculiar industrial magnate, who once offered to build free of charge a fleet by which Israel could colonize and make fertile otherwise desert areas of Mars, had asked for and may possibly receive a staggering and unprecedented loan of

“This isn’t gossip,” Joe Chip said to the ’pape machine. “This is speculation about fiscal transactions. Today I want to read about which TV star is sleeping with whose drug-addicted wife.” He had as usual not slept well, at least in terms of REM—rapid eye movement—sleep. And he had resisted taking a soporific because, very unfortunately, his week’s supply of stimulants, provided him by the autonomic pharmacy of his conapt building, had run out—due, admittedly, to his own oral greed, but nonetheless gone. By law he could not approach the pharmacy for more until next Tuesday. Two days away, two long days.

The ’pape machine said, “Set the dial for low gossip.”

He did so and a second scroll, excreted by the ’pape machine without delay, emerged; he zommed in on an excellent caricature drawing of Lola Herzburg-Wright, licked his lips with satisfaction at the naughty exposure of her entire right ear, then feasted on the text.

Accosted by a cutpurse in a fancy NY after-hours mowl the other night, Lola Herzburg-Wright bounced a swift right jab off the chops of the do-badder which sent him reeling onto the table where King Egon Groat of Sweden and an unidentified miss with astonishingly large

The ring-construct of his conapt door jangled; startled, Joe Chip glanced up, found his cigarette attempting to burn the Formica surface of his neoteakwood table, coped with that, then shuffled blearily to the speaktube mounted handily by the release bolt of the door. “Who is it?” he grumbled; checking with his wrist watch, he saw that eight o’clock had not arrived. Probably the rent robot, he decided. Or a creditor. He did not trigger off the release bolt of the door.

An enthusiastic male voice from the door’s speaker exclaimed, “I know it’s early, Joe, but I just hit town. G. G. Ashwood here; I’ve got a firm prospect that I snared in Topeka—I read this one as magnificent, and I want your confirmation.”

Chip said, “I don’t have my test equipment in the apt.”

“I’ll shoot over to the shop and pick it up for you.”

“It’s not at the shop.” Reluctantly, he admitted, “It’s in my car. I didn’t get around to unloading it last night.” In actuality, he had been too pizzled on papapot to get the trunk of his hovercar open. “Can’t it wait until after nine?” he asked irritably. G. G. Ashwood’s unstable manic energy annoyed him even at noon…This, at seven forty, struck him as downright impossible: worse even than a creditor.

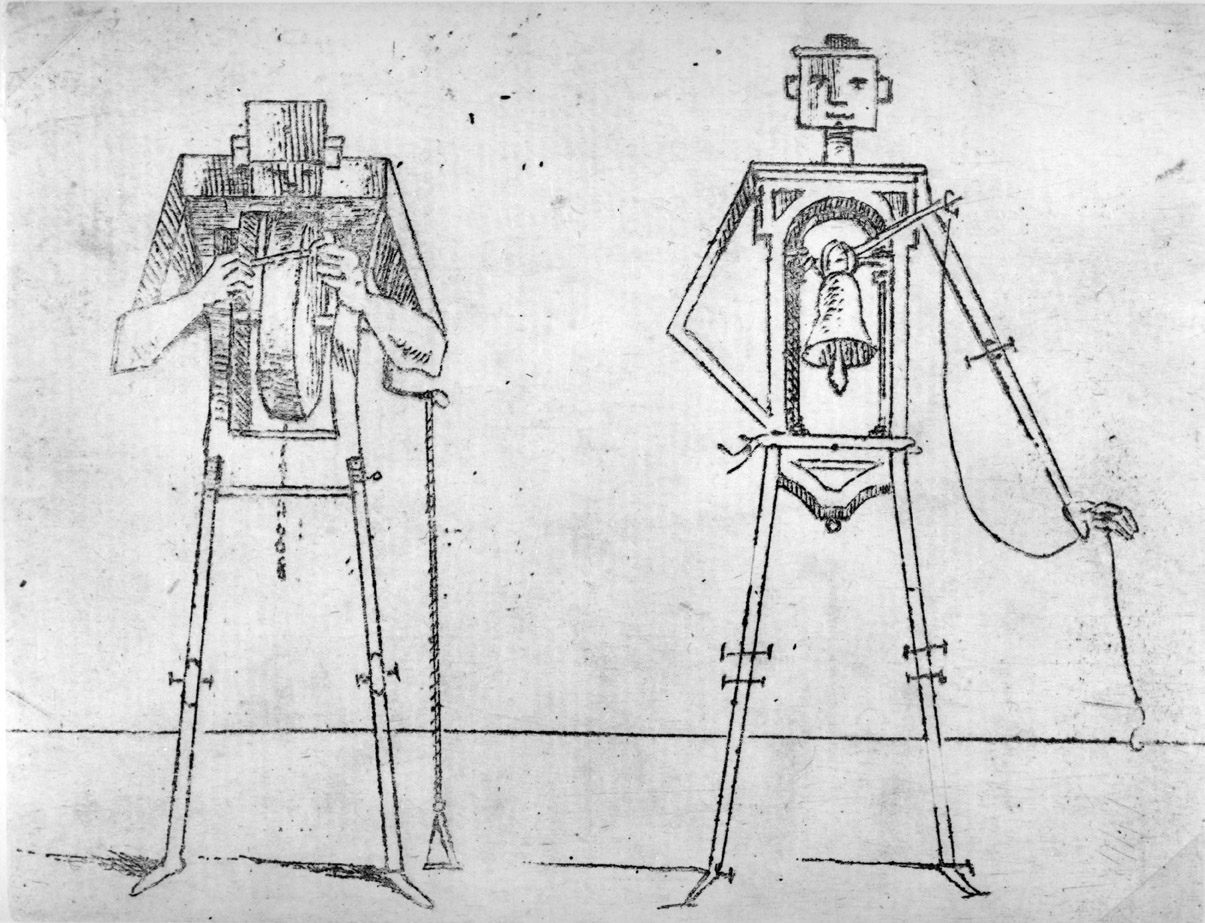

Bizarre Figures, by Giovanni Battista Bracelli, 1624.

“Chip, dearie, this is a sweet number, a walking symposium of miracles that’ll curl the needles of your gauges and, in addition, give new life to the firm, which it badly needs. And furthermore—”

“It’s an anti what?” Joe Chip asked. “Telepath?”

“I’ll lay it on you right out in front,” G. G. Ashwood declared. “I don’t know. Listen, Chip.” Ashwood lowered his voice. “This is confidential, this particular one. I can’t stand down here at the gate gum-flapping away out loud; somebody might overhear. In fact I’m already picking up the thoughts of some gloonk in a ground-level apt; he—”

“Okay,” Joe Chip said, resigned. Once started, G. G. Ashwood’s relentless monologues couldn’t be aborted anyhow. He might as well listen to it. “Give me five minutes to get dressed and find out if I’ve got any coffee left in the apt anywhere.”

“You’ll like her,” G. G. Ashwood stated energetically. “Although, as often happens, she’s the daughter of a—”

“Her?” In alarm Joe Chip said, “My apt’s unfit to be seen; I’m behind in my payments to the building clean-up robots—they haven’t been inside here for two weeks.”

“I read her mind and she doesn’t care.”

“How old is she?” Maybe, he thought, she’s only a child. Quite a few new and potential inertials were children, having developed their ability in order to protect themselves against their psionic parents.

“How old are you, dear?” G. G. Ashwood asked faintly, turning his head away to speak to the person with him. “Nineteen,” he reported to Joe Chip.

Well, that shot that. But now he had become curious. G. G. Ashwood’s razzle-dazzle wound-up tightness usually manifested itself in conjunction with attractive women; maybe this girl fell into that category. “Give me fifteen minutes,” he told G. G. If he worked fast, and skulked about in a clean-up campaign, and if he missed both coffee and breakfast, he could probably effect a tidy apt by then. At least it seemed worth trying.

He rang off, then searched in the cupboards of the kitchen for a broom (manual or self-powered) or vacuum cleaner (helium battery or wall-socket). Neither could be found. Evidently he had never been issued any sort of cleaning equipment by the building’s supply agency. Hell of a time, he thought, to find that out. And he had lived here four years.

Picking up the vidphone, he dialed 214, the extension for the maintenance circuit of the building. “Listen,” he said, when the homeostatic entity answered, “I’m now in a position to divert some of my funds in the direction of settling my bill vis-à-vis your clean-up robots. I’d like them up here right now to go over my apt. I’ll pay the full and entire bill when they’re finished.”

“Sir, you’ll pay your full and entire bill before they start.”

“I’ll charge my overdue bill against my Triangular Magic Key,” he informed his nebulous antagonist. “That will transfer the obligation out of your jurisdiction; on your books it’ll show as total restitution.”

“Plus fines, plus penalties.”

“I’ll charge those against my Heart-Shaped—”

“Mr. Chip, the Ferris & Brockman Retail Credit Auditing and Analysis Agency has published a special flier on you. Our recept-slot received it yesterday and it remains fresh in our minds. Since July you’ve dropped from a triple-G status creditwise to quadruple-G. Our department—in fact this entire conapt building—is now programmed against an extension of services and/or credit to such pathetic anomalies as yourself, sir. Regarding you, everything must hereafter be handled on a basic-cash subfloor. In fact, you’ll probably be on a basic-cash subfloor for the rest of your life. In fact—”

He hung up. And abandoned the hope of enticing and/or threatening the clean-up robots into entering his muddled apt. Instead, he padded into the bedroom to dress; he could do that without assistance.

Back in the kitchen he fished in his various pockets for a dime, and with it started up the coffeepot. Sniffing the—to him—very unusual smell, he again consulted his watch, saw that fifteen minutes had passed; he therefore vigorously strode to the apt door, turned the knob and pulled on the release bolt.The door refused to open. It said, “Five cents, please.”

He searched his pockets. No more coins; nothing. “I’ll pay you tomorrow,” he told the door. Again he tried the knob. Again it remained locked tight. “What I pay you,” he informed it, “is in the nature of a gratuity; I don’t have to pay you.”

“I think otherwise,” the door said. “Look in the purchase contract you signed when you bought this conapt.”

In his desk drawer he found the contract; since signing it he had found it necessary to refer to the document many times. Sure enough; payment to his door for opening and shutting constituted a mandatory fee. Not a tip.

“You discover I’m right,” the door said. It sounded smug.

From the drawer beside the sink Joe Chip got a stainless-steel knife; with it he began systematically to unscrew the bolt assembly of his apt’s money-gulping door.

“I’ll sue you,” the door said as the first screw fell out.

Joe Chip said, “I’ve never been sued by a door. But I guess I can live through it.”

A knock sounded on the door. “Hey, Joe, baby, it’s me, G. G. Ashwood. And I’ve got her right here with me. Open up.”

“Put a nickel in the slot for me,” Joe said. “The mechanism seems to be jammed on my side.”

A coin rattled down into the works of the door; it swung open and there stood G. G. Ashwood with a brilliant look on his face. It pulsed with sly intensity, an erratic, gleaming triumph as he propelled the girl forward and into the apt.

“This is Pat,” G. G. Ashwood said, his arm, with ostentatious familiarity, around the girl’s waist. “Never mind her last name.” Square and puffy, like an overweight brick, wearing his usual mohair poncho, apricot-colored felt hat, argyle ski socks, and carpet slippers, he advanced toward Joe Chip, self-satisfaction smirking from every molecule in his body: he had found something of value here, and he meant to make the most of it. “Pat, this is the company’s highly skilled, first-line electrical-type tester. Where’s your test equipment, Joe? We’re wasting time.”

Joe said to Pat, “What is your anti-talent?”

“It’s hard to explain.”

“Like I say,” G. G. Ashwood said, “it’s unique; I’ve never heard of it before.”

“Which psi talent does it counteract?” Joe asked the girl.

“Precog,” Pat said. “I guess.” She indicated G. G. Ashwood, whose smirk of enthusiasm had not dimmed. “Your scout Mr. Ashwood explained it to me. I knew I did something funny; I’ve always had these strange periods in my life, starting in my sixth year. I never told my parents, because I sensed that it would displease them.”

“Are they precogs?” Joe asked.

“Yes.”

“You’re right. It would have displeased them. But if you used it around them—even once—they would have known. Didn’t they suspect? Didn’t you interfere with their ability?”

Pat said, “I—” She gestured. “I think I did interfere, but they didn’t know it.” Her face showed bewilderment.

Medieval missionary discovering the point where heaven and earth meet, twentieth-century coloration of black-and-white engraving from The Atmosphere, by Camille Flammarion, 1888.

“Let me explain,” Joe said, “how the anti-precog generally functions. Functions, in fact, in every case we know of. The precog sees a variety of futures, laid out side by side like cells in a beehive. For him one has greater luminosity, and this he picks. Once he has picked it the anti-precog can do nothing; the anti-precog has to be present when the precog is in the process of deciding, not after. The anti-precog makes all futures seem equally real to the precog; he aborts his talent to choose at all. A precog is instantly aware when an anti-precog is nearby because his entire relation to the future is altered. In the case of telepaths a similar impairment—”

“She goes back in time,” G. G. said.

Joe stared at him.

“Back in time,” G. G. repeated, savoring this; his eyes shot shafts of significance to every part of Joe Chip’s kitchen. “The precog affected by her still sees one predominant future; like you said, the one luminous possibility. And he chooses it, and he’s right. But why is it right? Why is it luminous? Because this girl—” He shrugged in her direction. “Pat controls the future; that one luminous possibility is luminous because she’s gone into the past and changed it. By changing it, she changes the present, which includes the precog; he’s affected without knowing it and his talent seems to work, whereas it really doesn’t. So that’s one advantage of her antitalent over other anti-precog talents. The other—and greater—is that she can cancel out the precog’s decision after he’s made it. She can enter the situation later on, and this problem has always hung us up, as you know; if we didn’t get in there from the start we couldn’t do anything. In a way, we never could truly abort the precog ability as we’ve done with the others, right? Hasn’t that been a weak link in our services?” He eyed Joe Chip expectantly.

“Interesting,” Joe said presently.

Pat said, “I can change the past, but I don’t go into the past; I don’t time-travel, as you want your tester to think.”

“How do you change the past?” Joe asked.

“I think about it. One specific aspect of it, such as one incident, or something somebody said. Or a little thing that happened that I wish hadn’t happened. The first time I did this, as a child—”

“When she was six years old,” G. G. broke in, “living in Detroit, with her parents of course, she broke a ceramic antique statue that her father treasured.”

“Didn’t your father foresee it?” Joe asked her. “With his precog ability?”

“He foresaw it,” Pat answered, “and he punished me the week before I broke the statue. But he said it was inevitable; you know the precog talent: they can foresee but they can’t change anything. Then after the statue did break—after I broke it, I should say—I brooded about it, and I thought about that week before it broke when I didn’t get any dessert at dinner and had to go to bed at five p.m. I thought Christ—or whatever a kid says—isn’t there some way these unfortunate events can be averted? My father’s precog ability didn’t seem very spectacular to me, since he couldn’t alter events; I still feel that way, a sort of contempt. I spent a month trying to will the damn statue back into one piece; in my mind I kept going back to before it broke, imagining what it had looked like…which was awful. And then one morning when I got up—I even dreamed about it at night—there it stood. As it used to be.” Tensely, she leaned toward Joe Chip; she spoke in a sharp, determined voice. “But neither of my parents noticed anything. It seemed perfectly normal to them that the statue was in one piece; they thought it had always been in one piece. I was the only one who remembered.” She smiled, leaned back, took one of his cigarettes and lit up.

“I’ll go get my test equipment from the car,” Joe said, starting toward the door.

“Five cents, please,” the door said as he seized its knob.

“Pay the door,” Joe said to G. G. Ashwood.

© 1969 by Philip K. Dick. Used with permission of The Wylie Agency LLC.

Philip K. Dick

From Ubik. His father having served in World War I, Dick later recalled, “What scared me the most was when my father would put on the gas mask. His face would disappear. This was not a human being at all.” Among the most influential American science-fiction writers, he published The Man in the High Castle in 1962 and Ubik in 1969. Many films have been adapted from his work, among them Blade Runner, Total Recall, and Minority Report.