Nothing is more despicable than respect based on fear.

—Albert Camus, 1940Torment Unforeseen

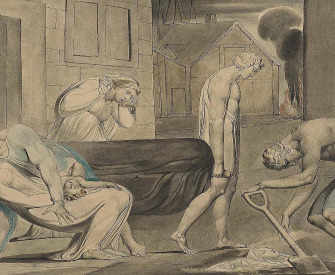

The wages of guilt.

Raskolnikov lay a very long while. Now and then he seemed to wake up, and at such moments he noticed that it was far into the night, but it did not occur to him to get up.

At last he noticed that it was beginning to get light. He was lying on his back, still dazed from his recent oblivion. Fearful, despairing cries rose shrilly from the street, sounds that he heard every night, indeed, under his window after two o’clock. They woke him up now.

He sat down on the sofa—and instantly recollected everything! All at once, in one flash, he recollected everything.

For the first moment, he thought he was going mad. A dreadful chill came over him; but the chill was from the fever that had begun long before in his sleep. Now he was suddenly taken with violent shivering, so that his teeth chattered and all his limbs were shaking. He opened the door and began listening, everything in the house was asleep. With amazement, he gazed at himself and everything in the room around him, wondering how he could have come in the night before without fastening the door, and have flung himself on the sofa without undressing, without even taking his hat off. It had fallen off and was lying on the floor near his pillow.

“If anyone had come in, what would he have thought? That I’m drunk but…”

He rushed to the window. There was light enough, and he began hurriedly looking himself all over from head to foot, all his clothes; were there no traces? But there was no doing it like that; shivering with cold, he began taking off everything and looking over again. He turned everything over to the last threads and rags, and mistrusting himself, went through his search three times.

But there seemed to be nothing, no trace, except in one place, where some thick drops of congealed blood were clinging to the frayed edge of his trousers. He picked up a big clasp knife and cut off the frayed threads.

Suddenly he remembered that the purse and the things he had taken out of the old woman’s box were still in his pockets. He had not thought till then of taking them out and hiding them! He had not even thought of them while he was examining his clothes! What next? Instantly he rushed to take them out and fling them on the table. When he had pulled out everything, and turned the pocket inside out to be sure there was nothing left, he carried the whole heap to the corner. The paper had come off the bottom of the wall and hung there in tatters. He began stuffing all the things into the hole under the paper. “They’re in! All out of sight, and the purse, too!” he thought gleefully, getting up and gazing blankly at the hole that bulged out more than ever. Suddenly he shuddered all over with horror. “My God!” he whispered in despair, “what’s the matter with me? Is that hidden? Is that the way to hide things?”

He had not reckoned on having trinkets to hide. He had only thought of money, and so had not prepared a hiding place.

“But now, now, what am I glad of?’’ he thought. “Is that hiding things? My reason’s deserting me—simply!”

He sat down on the sofa in exhaustion and was at once shaken by another unbearable fit of shivering. Mechanically, he drew from a chair beside him his old student’s winter coat, which was still warm though almost in rags, covered himself up with it, and once more sank into drowsiness and delirium. He lost consciousness.

Not more than five minutes had passed when he jumped up a second time and at once pounced in a frenzy on his clothes again.

“How could I go to sleep again with nothing done? Yes, yes. I have not taken the loop off the armhole! I forgot it, forgot a thing like that! Such a piece of evidence!”

The conviction that all his faculties, even memory, and the simplest power of reflection were failing him began to be an insufferable torture.

“Surely it isn’t beginning already! Surely it isn’t my punishment coming upon me? It is!”

For a long while, for some hours, he was haunted by the impulse to “go off somewhere at once, this moment, and fling it all away, so that it may be out of sight and done with, at once, at once!” Several times he tried to rise from the sofa but could not.

He was thoroughly woken up at last by a violent knocking at his door.

“Open, do, are you dead or alive? He keeps sleeping here!” shouted Nastasya, banging with her fist on the door. “For whole days together he’s snoring here like a dog! A dog he is, too. Open, I tell you. It’s past ten.”

He jumped up and sat on the sofa. The beating of his heart was a positive pain.

“Then who can have latched the door?” retorted Nastasya. “He’s taken to bolting himself in! As if he were worth stealing! Open, you stupid, wake up!”

He half rose, stooped forward, and unlatched the door.

His room was so small that he could undo the latch without leaving the bed. The porter and Nastasya were standing here.

Nastasya stared at him in a strange way. He glanced with a defiant and desperate air at the porter, who without a word held out a gray folded paper sealed with bottle wax.

“A notice from the office,” he announced, as he gave him the paper.

“From what office?”

“A summons to the police office, of course. You know which office.”

“To the police?…What for?…”

“How can I tell? You’re sent for, so you go.”

Raskolnikov made no response and held the paper in his hands, without opening it.

“Don’t you get up then,” Nastasya went on compassionately, seeing that he was letting his feet down from the sofa. “You’re ill, so don’t go. There’s no such hurry. What have you got there?”

He looked; in his right hand he held the shreds he had cut from his trousers, the sock, and the rags of the pocket. So he had been asleep with them in his hand. Afterward, reflecting on it, he remembered that, half waking up in his fever, he had grasped all this tightly in his hand and so fallen asleep again.

Lair of the Sea Serpent, by Elihu Vedder, c. 1899. © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Mrs. Harold G. Henderson, 1976.

Instantly he thrust them all under his greatcoat and fixed his eyes intently on her. Far as he was from being capable of rational reflection at that moment, he felt that no one would behave like that with a person who was going to be arrested. “But…the police?”

“You’d better have some tea! Yes? I’ll bring it, there’s some left.”

“No…I’m going. I’ll go at once,” he muttered, getting on his feet.

“As you please.”

She followed the porter out.

At once he rushed to the light to examine the sock and the rags.

“There are stains, but not very noticeable. All covered with dirt, and rubbed and already discolored. No one who had no suspicion could distinguish anything. Nastasya from a distance could not have noticed, thank God!” Then with a tremor, he broke the seal of the notice and began reading; he was a long while reading, before he understood. It was an ordinary summons from the district police station to appear that day at half past nine at the office of the district superintendent.

“But when has such a thing happened? I never have anything to do with the police! And why just today?” he thought in agonizing bewilderment. “Good God, only get it over soon!”

He was flinging himself on his knees to pray, but broke into laughter—not at the idea of prayer but at himself.

He began, hurriedly dressing. “If I’m lost, I am lost, I don’t care! Shall I put the sock on?” he suddenly wondered. “It will get dustier still and the traces will be gone.”

But no sooner had he put it on than he pulled it off again in loathing and horror. He pulled it off, but reflecting that he had no other socks, he picked it up and put it on again—and again he laughed.

“That’s all conventional, that’s all relative, merely a way of looking at it,” he thought in a flash, but only on the top surface of his mind, while he was shuddering all over. “There, I’ve got it on! I have finished by getting it on!”

But his laughter was quickly followed by despair.

Dread attends the unknown.

—Nadine Gordimer, 1998“No, it’s too much for me…” he thought. His legs shook. “From fear,” he muttered. His head swam and ached with fever. “It’s a trick! They want to decoy me there and confound me over everything,” he mused, as he went out onto the stairs—“the worst of it is, I’m almost light-headed…I may blurt out something stupid.”

On the stairs he remembered he was leaving all the things just as they were in the hole in the wall, “and very likely, it’s on purpose to search when I’m out,” he thought and stopped short. But he was possessed by such despair, such cynicism of misery, if one may so call it, that with a wave of his hand he went on. “Only to get it over!”

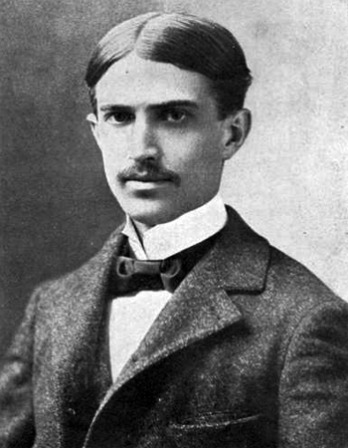

Fyodor Dostoevsky

From Crime and Punishment. Raskolnikov, the impoverished intellectual at the center of Dostoevsky’s novel, has awoken after murdering an elderly pawnbroker. “Questions that he cannot resolve well up in the murderer,” Dostoevsky wrote to his editor. “Feelings he had not foreseen or suspected torment his heart.” Written under great financial pressure, Crime and Punishment was the author’s second novel after returning from exile in Siberia and initially ran serially, as twelve segments in The Russian Messenger.