So! Here I am. I have been dining at the worthy Bagnol’s, where I found Madame de Coulanges in this charming apartment, embellished with the golden rays of the sun, where I have often seen you, almost as beautiful and as brilliant as he. The poor convalescent gave me a hearty welcome, and is now going to write two lines to you; it is, for all I know, something from the other world, which I am sure you will be very glad to hear.

She has been giving me an account of a new dress called “transparencies.” Pray, have you heard of it? It is an entire suit of the finest gold and azure brocade that can be seen, over which is a black robe, either of beautiful English lace, or velvet chenille like the winter laces you have seen; this occasions the name of transparency, which is, you see, a black suit, and a suit of gold and azure, or any other color, according to the fancy of the wearer, as is all the fashion at present. This was the dress worn at the ball on St. Hubert’s Day, which lasted a whole half hour, for nobody would dance. The king pushed Madame de Heudicourt into the middle of the room by main force; she obeyed, but at length the combat ended for want of combatants. The fine embroidered bodices destined for Villers-Cotterêts serve to walk out on an evening, and were worn on St. Hubert’s Day. The prince informed the ladies at Chantilly that their transparencies would be a thousand times more beautiful if they would wear them next to their skin, which I very much doubt. The Granceis and Monacos did not share in the amusements, because the mother of the latter is ill, and the mother of the angels has been at death’s door. It is said, the Marchioness de La Ferté has been in labor there, ever since Sunday, and that Bouchet is at his wit’s end.

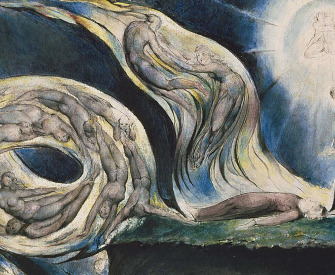

Battista Sforza and Federico da Montefeltro, by Piero della Francesca, c. 1472. © Nicolo Orsi Battaglini / Art Resource, NY.

Monsieur de Langlée, a tailor at court, has made Madame de Montespan a present of a robe of gold cloth, on a gold ground, with a double gold border embroidered and worked with gold, so that it makes the finest gold stuff ever imagined by the wit of man. It was contrived by fairies in secret, for no living being could have conceived anything so beautiful. The manner of presenting it was equally mysterious. Madame de Montespan’s mantua maker carried home the suit she had bespoke, having made it to fit ill on purpose; you need not be told what exclamations and scoldings there were upon the occasion. “Madam,” said the mantua maker, trembling with fear, “as there is so little time to alter it in, will you have the goodness to try whether this other dress may not fit you better?” It was produced. “Ah!” cried the lady, “how beautiful! What an elegant stuff is this! Pray, where did you get? It must have fallen from the clouds, for a mortal could never have executed anything like it.” The dress was tried on; it fitted to a hair. In came the king. “It was made for you, madam,” said the mantua-maker. Immediately it was concluded that it must be a present from someone; but from whom? was the question. “It is Langlée,” said the king. “It must be Langlée,” said Madame de Montespan; “nobody but Langlée could have thought of so magnificent a present—it is Langlée, it is Langlée!” Everybody exclaims, “It is Langlée, it is Langlée!” The echoes repeat the sound. And I, my child, to be in the fashion, say, “It is Langlée.”

From a letter. Marie de Rabutin-Chantal, marquise de Sévigné, was married for seven years before losing her husband in a duel he fought over his mistress in 1651. As a widow with two children, she spent most of her time at court and the Hôtel de Rambouillet in Paris. The marquise wrote more than 1,700 letters to her daughter. “In truth,” wrote Sévigné, “between friends one ought to let the pens trot as they like.” Monsieur Langlée, according to the Duc de Saint-Simon, was “a master of fashions and of fêtes” at Versailles.

Back to Issue