How absurd men are! They never use the liberties they have, they demand those they do not have. They have freedom of thought, they demand freedom of speech.

—Søren Kierkegaard, 1843Borrowing a Simile

Walt Whitman marvels at the ceaseless evolution of slang in America.

Viewed freely, the English language is the accretion and growth of every dialect, race, and range of time, and is both the free and compacted composition of all. From this point of view, it stands for language in the largest sense, and is really the greatest of studies. It involves so much, is indeed a sort of universal absorber, combiner, and conqueror. The scope of its etymologies is the scope not only of man and civilization, but the history of nature in all departments and of the organic universe, brought up to date; for all are comprehended in words, and their backgrounds. This is when words become vitalized and stand for things, as they unerringly and soon come to do, in the mind that enters on their study with fitting spirit, grasp, and appreciation.

Slang, profoundly considered, is the lawless germinal element, below all words and sentences, and behind all poetry, and proves a certain perennial rankness and protestantism in speech. As the United States inherit by far their most precious possession—the language they talk and write—from the Old World, under and out of its feudal institutes, I will allow myself to borrow a simile even of those forms furthest removed from American democracy. Considering language then as some mighty potentate, into the majestic audience hall of the monarch ever enters a personage like one of Shakespeare’s clowns, and takes position there, and plays a part even in the stateliest ceremonies. Such is slang, or indirection, an attempt of common humanity to escape from bald literalism and express itself illimitably, which in highest walks produces poets and poems, and doubtless in prehistoric times gave the start to, and perfected, the whole immense tangle of the old mythologies. For, curious as it may appear, it is strictly the same impulse source, the same thing. Slang, too, is the wholesome fermentation or eructation of those processes eternally active in language, by which froth and specks are thrown up—mostly to pass away, though occasionally to settle and permanently crystallize.

To make it plainer, it is certain that many of the oldest and solidest words we use were originally generated from the daring and license of slang. In the processes of word formation, myriads die, but here and there the attempt attracts superior meanings, becomes valuable and indispensable, and lives forever. Thus the term “right” means literally only straight. “Wrong” primarily meant twisted, distorted. “Integrity” meant oneness. “Spirit” meant breath, or flame. A “supercilious” person was one who raised his eyebrows. To “insult” was to leap against. If you “influenced” a man, you but flowed into him. The Hebrew word which is translated “prophesy” meant to bubble up and pour forth as a fountain. The enthusiast bubbles up with the spirit of God within him, and it pours forth from him like a fountain. The word prophecy is misunderstood. Many suppose that it is limited to mere prediction; that is but the lesser portion of prophecy. The greater work is to reveal God. Every true religious enthusiast is a prophet.

Language, be it remembered, is not an abstract construction of the learned or of dictionary makers but is something arising out of the work, needs, ties, joys, affections, tastes, of long generations of humanity, and has its bases broad and low, close to the ground. Its final decisions are made by the masses, people nearest the concrete, having most to do with actual land and sea. It impermeates all, the past as well as the present, and is the grandest triumph of the human intellect. “Those mighty works of art,” says John Addington Symonds, “which we call languages, in the construction of which whole peoples unconsciously cooperated, the forms of which were determined not by individual genius, but by the instincts of successive generations, acting to one end, inherent in the nature of the race—those poems of pure thought and fancy, cadenced not in words, but in living imagery, fountainheads of inspiration, mirrors of the mind of nascent nations, which we call mythologies—these surely are more marvelous in their infantine spontaneity than any more mature production of the races which evolved them. Yet we are utterly ignorant of their embryology; the true science of origins is yet in its cradle.”

Daring as it is to say so, in the growth of language it is certain that the retrospect of slang from the start would be the recalling from their nebulous conditions of all that is poetical in the stores of human utterance. Moreover, the honest delving, as of late years, by the German and British workers in comparative philology, has pierced and dispersed many of the falsest bubbles of centuries and will disperse many more. It was long recorded that in Scandinavian mythology the heroes in the Norse paradise drank out of the skulls of their slain enemies. Later investigation proves the word taken for skulls to mean “horns” of beasts slain in the hunt. And what reader had not been exercised over the traces of that feudal custom, by which seigneurs warmed their feet in the bowels of serfs, the abdomen being opened for the purpose? It now is made to appear that the serf was only required to submit his unharmed abdomen as a foot cushion while his lord supped and was required to chafe the legs of the seigneur with his hands.

It is curiously in embryos and childhood, and among the illiterate, we always find the groundwork and start, of this great science, and its noblest products. What a relief most people have in speaking of a man not by his true and formal name, with a “Mister” to it, but by some odd or homely appellative. The propensity to approach a meaning not directly and squarely but by circuitous styles of expression seems indeed a born quality of the common people everywhere, evidenced by nicknames, and the inveterate determination of the masses to bestow subtitles, sometimes ridiculous, sometimes very apt.

I find the same rule in the people’s conversations everywhere. I heard this among the men of the city horse-cars, where the conductor is often called a “snatcher” (i.e., because his characteristic duty is to constantly pull or snatch the bellstrap, to stop or go on.) Two young fellows are having a friendly talk, amid which, says first conductor, “What did you do before you was a snatcher?” Answer of second conductor: “Nailed.” (Translation of answer: “I worked as carpenter.”) “What is a ‘boom’”? says one editor to another. “Esteemed contemporary,” says the other, “a boom is a bulge.” “Barefoot whiskey” is the Tennessee name for the undiluted stimulant. In the slang of the New York common restaurant waiters, a plate of ham and beans is known as “stars and stripes,” codfish balls as “sleeve buttons,” and hash as “mystery.”

The Western states of the Union are, however, as may be supposed, the special areas of slang, not only in conversation, but in names of localities, towns, rivers, etc. A Nevada paper chronicles the departure of a mining party from Reno: “The toughest set of roosters that ever shook the dust off any town left Reno yesterday for the new mining district of Cornucopia. They came here from Virginia. Among the crowd were four New York cockfighters, two Chicago murderers, three Baltimore bruisers, one Philadelphia prizefighter, four San Francisco hoodlums, three Virginia beats, two Union Pacific roughs, and two check guerrillas.” Among the far-West newspapers, have been, or are, The Fairplay (Colorado) Flume, The Solid Muldoon, of Ouray, The Tombstone Epitaph, of Nevada, The Jimplecute, of Texas, and The Bazoo, of Missouri. Shirttail Bend, Whiskey Flat, Puppytown, Wild Yankee Ranch, Squaw Flat, Rawhide Ranch, Loafer’s Ravine, Squitch Gulch, Toenail Lake, are a few of the names of places in Butte County, California.

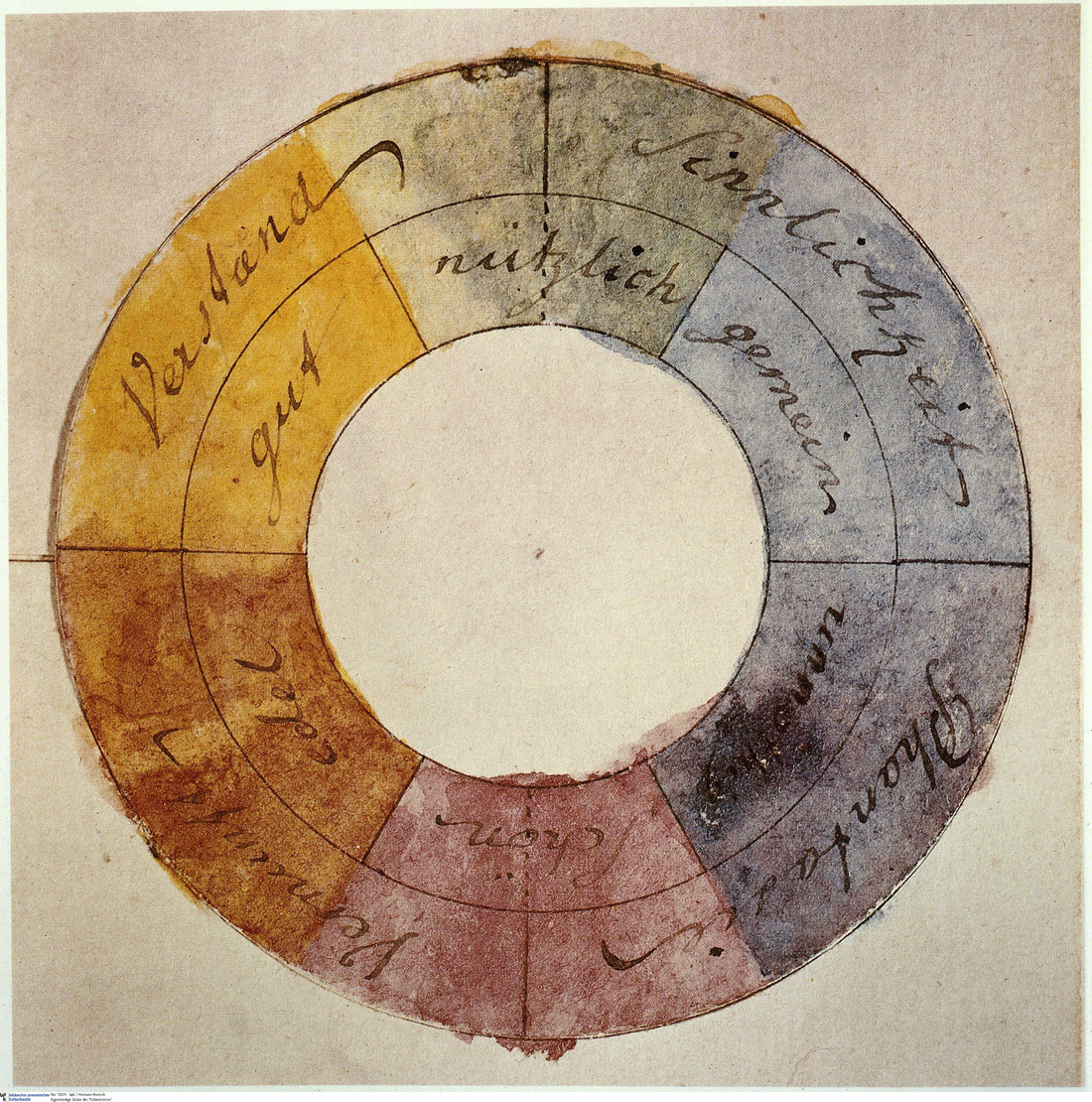

Color circle, by Johann Wolfgang von Goethe, 1809. Goethe House, Frankfurt, Germany.

Perhaps indeed no place or term gives more luxuriant illustrations of the fermentation processes I have mentioned, and their froth and specks, than those Mississippi and Pacific Coast regions, at the present day. Hasty and grotesque as are some of the names, others are of an appropriateness and originality unsurpassable. This applies to the Indian words, which are often perfect. Oklahoma is proposed in Congress for the name of one of our new Territories. Hog-eye, Lick-skillet, Rake-pocket, and Steal-easy are the names of some Texan towns.

Certainly philologists have not given enough attention to this element and its results, which, I repeat, can probably be found working everywhere today, with as much life and activity as in far-back Greece or India, under prehistoric ones. Then the wit—the rich flashes of humor and genius and poetry—darting out often from a gang of laborers, railroad men, miners, drivers or boatmen! How often have I hovered at the edge of a crowd of them to hear their repartees and impromptus! You get more real fun from half an hour with them than from the books of all “the American humorists.”

The science of language has large and close analogies in geological science, with its ceaseless evolution, its fossils, and its numberless submerged layers and hidden strata, the infinite go-before of the present. Or perhaps language is more like some vast living body, or perennial body of bodies. And slang not only brings the first feeders of it but is afterward the start of fancy, imagination, and humor, breathing into its nostrils the breath of life.

Walt Whitman

From “Slang in America.” Whitman became the editor of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle in 1846 but was fired two years later for his support of the antislavery Free Soil Party. Unable to find a publisher for the first edition of Leaves of Grass in 1855, he sold a house to pay for its printing; the book appeared without his name and fell on mostly stony ground. Ralph Waldo Emerson, however, pronounced it “the most extraordinary piece of wit and wisdom” that America had yet produced.