Modesty is a virtue not often found among poets, for almost every one of them thinks himself the greatest in the world.

—Miguel de Cervantes, 1615Discouraging an Author

Anton Chekhov escapes an intolerable situation.

“Pavel Vasilich, a certain lady is asking for you,” reported Luke, his butler. “She has been waiting for nearly an hour.”

Pavel Vasilich had just finished his breakfast. When he heard about the lady, he wrinkled his nose as he said, “Tell her to go to hell. Tell her that I am busy right now.”

“Pavel Vasilich, this is the fifth time she has come to see you already. She says that it is very important for her to see you. She is on the verge of bursting into tears.”

“Fine. Invite her into my office.”

Pavel Vasilich put on his jacket, slowly took a pen in one hand and a book in the other hand, and, pretending to be very busy, entered his office.

His visitor was already there, waiting for him. She was a big, chubby lady with a fleshy face, wearing glasses, dressed more than decency required. She had a sophisticated hat, the top of which was a gray bird with a design of four ribbons around it. As soon as she saw the master of the house, she clasped her hands together as if in prayer and lifted her eyes to the ceiling.

“Certainly, you do not remember me,” she started in a deep, male-sounding tenor voice, obviously showing her excitement. “I had the pleasure of meeting you at the Krutsky party. My name is Mrs. Grasshopper.”

“Oh, I remember. Well, please take a seat. What can I do for you?”

“You see … um … I … well,” the lady muttered as she tried to continue. “I am Mrs. Grasshopper. I am a great admirer of your talent, and I always read your articles with great pleasure. Do not think that I am flattering. God forbid! I am just saying what you deserve. I always read your work, always. I too am an author. Actually, I do not dare call myself a female writer, but I have a little drop of honey in the general beehive of literature, so to speak. I have published, at different times, three stories for children. I have also done a lot of translating, and my brother worked at the Business Review Newspaper.”

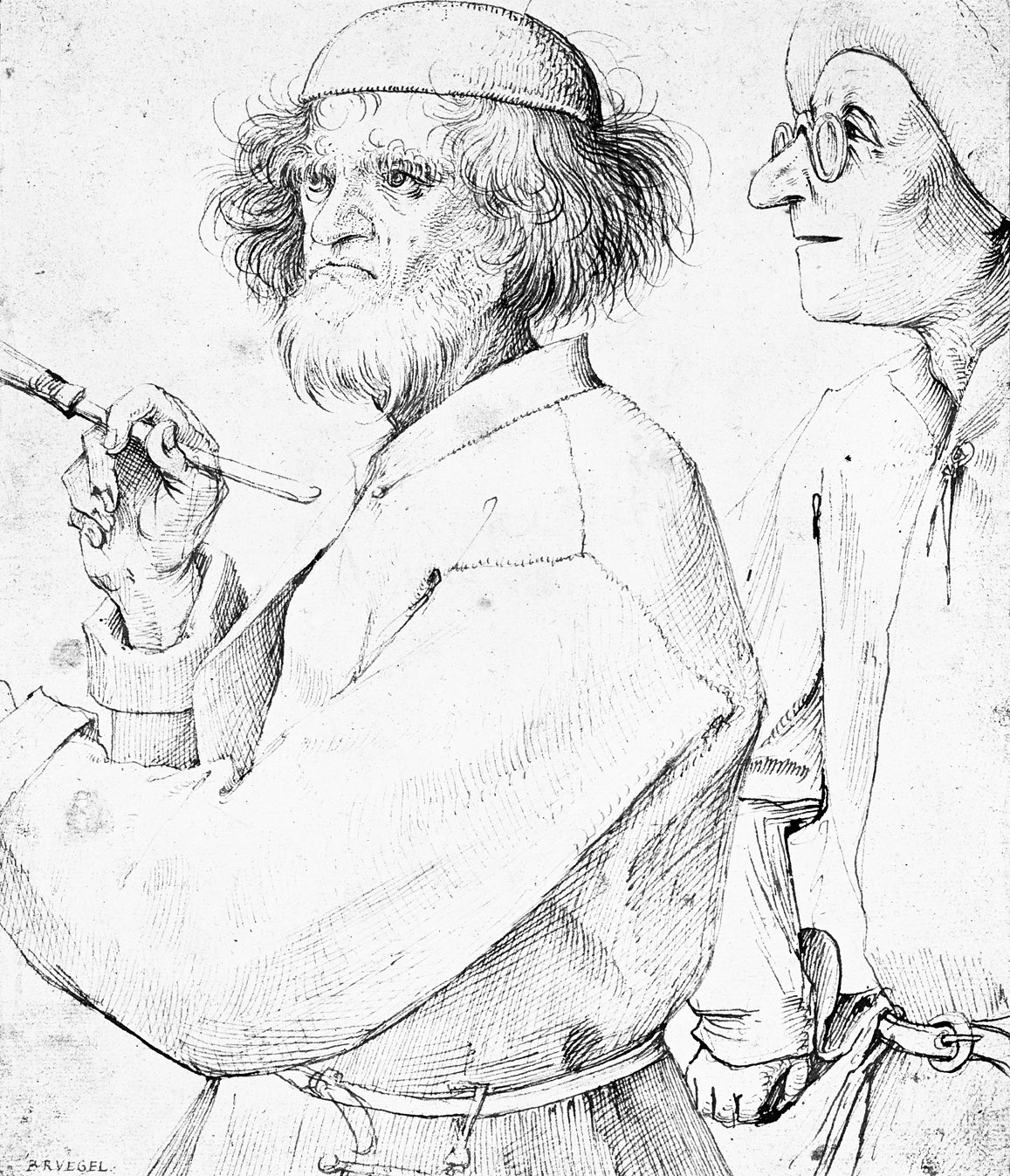

Painter and his Patron, by Pieter Brueghel the Elder, c. 1565. The Albertina, Vienna, Austria.

“So what is it exactly that I can do for you today?”

“You see,” Mrs. Grasshopper lowered her glance and blushed as she began, “I know your talent, and I know your views, but I would like your opinion, or, to be exact, your advice. As you know, pardon my French, I have an outline in the form of a theatrical drama, and before submitting it officially, I would like your opinion.”

Mrs. Grasshopper, with an expression of a bird caught in a net, rummaged nervously in the folds of her dress and pulled out a thick notebook.

Now, Pavel Vasilich loved only his own writing. Pieces written by others, which he had to listen to often, reminded him of a cannon being aimed at his head. On seeing the notebook, he became fearful and hastily said, “Please leave it here. I will read it later.”

“Pavel Vasilich,” Mrs. Grasshopper said dramatically, standing up and again folding her hands, as if in prayer, “I know you are busy. I know that every minute counts for you, and I know that you, in the depths of your soul, are sending me to hell, but please be so kind and let me read my drama to you now. Please,” she implored.

“It was a pleasure to meet you.” Pavel Vasilich now felt bewildered. “But my dear lady, I am very busy at the moment. I have somewhere to go.”

“Pavel Vasilich.” The lady groaned as her eyes filled with tears. “I must insist. I know I am an impudent, saucy, impertinent, cheeky creature, but please, please help me! Tomorrow I am going to the remote town of Kazan, and before I go I would like to know your opinion. Just give me half an hour of your time, just one half hour, I implore you!”

Pavel Vasilich was a weak person, and he could not refuse her request. When he saw the lady begin to cry and to kneel in front of him, he became even more confused and murmured, seemingly at a loss, “Well, then … All right, all right, please read it, I will listen. Keep in mind, though, that I only have half an hour for you.”

Mrs. Grasshopper gave a shriek of joy, took off her hat, sat down, and started reading. First she read about a butler and a cleaning lady tidying up a luxurious parlor, discussing a landlady, Anna Sergeievna, who built a school and a hospital in their little town out of charity. After the butler left, the maid gave a lengthy monologue that education is good and ignorance is bad for you.

Then Mrs. Grasshopper brought the butler back to the parlor and gave him a lengthy monologue that the landlord, who was a general, did not tolerate the liberal views of his daughter and wanted her to marry a rich officer of the Guard, and who said that common people could be saved by keeping them in ignorance.

After the servants left, the landlady appeared by herself and announced to the spectators that she had not slept the whole night and had been thinking about Valentine Ivanovich, the poor son of a village teacher who was supporting his sick father. Valentine studied at the university, but he did not believe in love, and he had no purpose in life. He was expecting his death, and the landlady was going to save him.

Pavel Vasilich half listened to the reading of the drama, and thought of his bed with great longing. He looked angrily at Mrs. Grasshopper and could not follow a single word she was reading. He thought the following: “You were brought here by the devil himself. Why should I listen to your nonsense? Why should I suffer sitting through your drama? Oh my God, her notebook is so thick! This is torture of the highest degree!”

“Do you believe that this monologue is a little bit too long?” Mrs. Grasshopper asked, lifting her eyes from her reading.

Pavel Vasilich had not been listening to the monologue. He got confused and said in such a guilty tone, as if it were not the lady but he who had written this monologue, “Not at all! It is very nice!”

Mrs. Grasshopper beamed with happiness and continued with her reading.

In the middle of scene sixteen, Pavel Vasilich yawned and then snapped his teeth, a noise much like the sound made by dogs when they catch flies or insects. He instantly feared that this noise had been heard by her and quickly put an expression of friendly attention on his face.

“Scene seventeen,” she read out loud.

“Where is the end of all this?” he thought. “Oh, my God! If this torture continues for ten more minutes, I will scream for help!”

Reading faster and louder, the lady raised her voice, “The end of act one. The curtain falls.”

Pavel Vasilich made a small movement and sighed with relief. He made to stand up from his chair, but Mrs. Grasshopper quickly flipped the page and started reading very fast, “The scene in the country. There is a school to the right, and the hospital to the left. You can see the local people sitting on the steps of the hospital, talking to each other quietly.”

“Excuse me,” Pavel Vasilich interrupted her. “How many acts do you have altogether?”

“Five acts. The play consists of five acts,” Mrs. Grasshopper repeated, and then continued quickly, as if afraid that her listener would leave. “Valentine is looking out of the school window. You can see in the background the local farmers bringing their belongings into the pub to pawn them and spend the money on drink.”

With the feeling of being slowly executed, or no possibility of parole, Pavel Vasilich hopelessly waited for the end of her reading. He could hardly keep his eyes open and keep up the expression of attention on his face. Sometime in the future, the lady would stop reading and leave. That time seemed so remote that he dared not even think about it.

“Tru-du-du,” Mrs. Grasshopper’s voice rang suddenly in his ears. “Buzz-buzz. Tru-tu-tu. Buzz.”

“I forgot to take some soda and medication for my stomach,” he thought to himself.

“What was I thinking about? Oh yes, baking soda. I must have some irritation in my stomach. Isn’t it strange that Mr. Smirnovsky drinks vodka all day long and has no irritation. Look, a little bird on the windowsill outside. A sparrow.”

Pavel Vasilich made an effort to open his heavy eyelids, yawned without opening his mouth, and looked at Mrs. Grasshopper. She began to sway and rock in his eyes, then she became three-headed, and one of her heads started growing and pushed against the ceiling.

Valentine: No. Let me go!

Anna: [scared] Why?

Valentine: She is so pale. [addressing her] Do not try to find out why. I would better die. You will never learn my reasons for leaving.

Anna: [after a pause] You cannot leave like this.

Mrs. Grasshopper started to swell and to grow, and turned into a huge monster. Then she blended with the gray air of the office. He could only see her talking mouth. And then she became very small, as small as a perfume bottle. After that she swayed from side to side and together with the desk moved into a remote corner of the room.

Valentine: [holding Anna in his embrace] You brought me back to life; you showed me the purpose of life! You revived me as a spring rain revives the wakening earth. But it is too late, too late! I am sick with terminal tuberculosis.

Pavel Vasilich trembled and looked through cloudy eyes at Mrs. Grasshopper. For a minute, he looked at her, motionless, without understanding anything.

“Act two. The same actors together with the baron, the police officer, and the witnesses.”

Valentine: Take me! I am yours.

Anna: Take me too! I am his. Finally! And you can take me. I am yours. I love him more than life!

Baron: Anna, you forgot that you are killing your father with this news, this kind of behavior.

Mrs. Grasshopper again began to swell.

Looking around him with the desperation of a wild animal, Pavel Vasilich stood up from his chair, cried out in an unnatural voice, grabbed a very heavy file from his desk and, without understanding what he was doing, hit Mrs. Grasshopper on her head.

“You can take me to the police station. I killed her!” he said a minute later to the people who ran into his office.

The jury found him not guilty, under the circumstances.

Translated by Peter Sekirin. © 2008 by Pegasus Books. Used with permission of Pegasus Books.

Anton Chekhov

From “Drama.” The author of Uncle Vanya and The Seagull published his first story at the age of twenty in 1880 and his first book in 1884, the same year he graduated with a medical degree from Moscow University and contracted tuberculosis. Of his two vocations he said, “I regard medicine as my lawful wife and literature as my mistress, who is dearer to me than a wife.”