Where the telescope ends, the microscope begins. Which of these two has the grander view?

—Victor Hugo, 1862Destroying the Competition

Charlotte Brontë with a message from the Luddites.

Mr. Moore was but half a Briton, and scarcely that. He came of a foreign ancestry by the mother’s side and was himself born and partly reared on a foreign soil. A hybrid in nature, it is probable he had a hybrid’s feeling on many points—patriotism for one.

It is likely that he was unapt to attach himself to parties, to sects, even to climes and customs. It is not impossible that he had a tendency to isolate his individual person from any community amid which his lot might temporarily happen to be thrown, and that he felt it to be his best wisdom to push the interests of Robert Gérard Moore, to the exclusion of philanthropic consideration for general interests, with which he regarded the said Gérard Moore as in a great measure disconnected. Trade was Mr. Moore’s hereditary calling—the Gérards of Antwerp had been merchants for two centuries back. Once they had been wealthy merchants, but the uncertainties, the involvements of business had come upon them. Disastrous speculations had loosened by degrees the foundations of their credit. The house had stood on a tottering base for a dozen years, and at last, in the shock of the French Revolution, it had rushed down a total ruin. In its fall was involved the English and Yorkshire firm of Moore, closely connected with the Antwerp house, and of which one of the partners, resident in Antwerp, Robert Moore, had married Hortense Gérard, with the prospect of his bride inheriting her father Constantine Gérard’s share in the business. She inherited but his share in the liabilities of the firm, and these liabilities, though duly set aside by a composition with creditors, some said her son Robert accepted, in his turn, as a legacy, and that he aspired one day to discharge them and to rebuild the fallen house of Gérard and Moore on a scale at least equal to its former greatness. It was even supposed that he took bypast circumstances much to heart, and if a childhood passed at the side of a saturnine mother, under foreboding of coming evil, and a manhood drenched and blighted by the pitiless descent of the storm could painfully impress the mind, his probably was impressed in no golden characters.

If, however, he had a great end of restoration in view, it was not in his power to employ great means for its attainment; he was obliged to be content with the day of small things. When he came to Yorkshire, he—whose ancestors had owned warehouses in this seaport and factories in that inland town, had possessed their town house and their countryseat—saw no way open to him but to rent a cloth mill in an out-of-the-way nook of an out-of-the-way district, to take a cottage adjoining it for his residence, and to add to his possessions, as pasture for his horse and space for his cloth tenters, a few acres of the steep, rugged land that lined the hollow through which his millstream brawled. All this he held at a somewhat high rent (for these war times were hard, and everything was dear) of the trustees of the Fieldhead estate, then the property of a minor.

At the time this history commences, Robert Moore had lived but two years in the district, during which period he had at least proved himself possessed of the quality of activity. The dingy cottage was converted into a neat, tasteful residence. Of part of the rough land he had made garden ground, which he cultivated with singular, even with Flemish, exactness and care. As to the mill, which was an old structure and fitted up with old machinery now become inefficient and out-of-date, he had from the first evinced the strongest contempt for all its arrangements and appointments. His aim had been to effect a radical reform, which he had executed as fast as his very limited capital would allow, and the narrowness of that capital, and consequent check on his progress, was a restraint which galled his spirit sorely. Moore ever wanted to push on: “Forward” was the device stamped upon his soul, but poverty curbed him. Sometimes (figuratively) he foamed at the mouth when the reins were drawn very tight.

In this state of feeling, it is not to be expected that he would deliberate much as to whether his advance was or was not prejudicial to others. Not being a native, nor for any length of time a resident of the neighborhood, he did not sufficiently care when the new inventions threw the old workpeople out of employ. He never asked himself where those to whom he no longer paid weekly wages found daily bread, and in this negligence, he only resembled thousands besides, on whom the starving poor of Yorkshire seemed to have a closer claim.

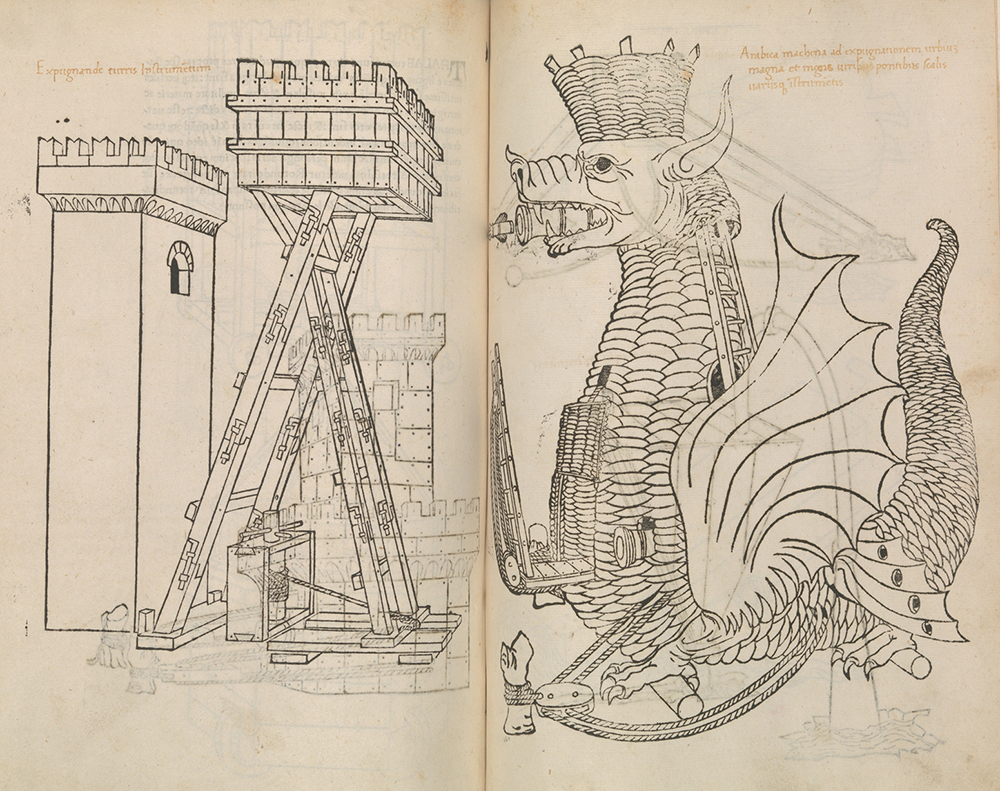

Illustrations from Roberto Valturio’s On the Military Arts, by Matteo de’ Pasti, 1472. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Harris Brisbane Dick Fund, 1926.

The period of which I write was an overshadowed one in British history, and especially in the history of the northern provinces. War was then at its height. Europe was all involved therein. England, if not weary, was worn with long resistance—yes, and half her people were weary, too, and cried out for peace on any terms. National honor was become a mere empty name, of no value in the eyes of many, because their sight was dim with famine, and for a morsel of meat, they would have sold their birthright.

The Orders in Council, provoked by Napoleon’s Milan and Berlin decrees and forbidding neutral powers to trade with France, had, by offending America, cut off the principal market of the Yorkshire woolen trade and brought it consequently to the verge of ruin. Minor foreign markets were glutted and would receive no more. The Brazils, Portugal, Sicily, were all overstocked by nearly two years’ consumption. At this crisis certain inventions in machinery were introduced into the staple manufactures of the North which, greatly reducing the number of hands necessary to be employed, threw thousands out of work and left them without legitimate means of sustaining life. A bad harvest supervened. Distress reached its climax. Endurance, overgoaded, stretched the hand of fraternity to sedition. The throes of a sort of moral earthquake were felt heaving under the hills of the northern counties. But as is usual in such cases, nobody took much notice. When a food riot broke out in a manufacturing town, when a gig mill was burned to the ground or a manufacturer’s house was attacked, the furniture thrown into the streets and the family forced to flee for their lives, some local measures were or were not taken by the local magistracy: a ringleader was detected or, more frequently, suffered to elude detection; newspaper paragraphs were written on the subject, and there the thing stopped. As to the sufferers, whose sole inheritance was labor, and who had lost that inheritance—who could not get work, and consequently could not get wages, and consequently could not get bread—they were left to suffer on, perhaps inevitably left: it would not do to stop the progress of invention, to damage science by discouraging its improvements. The war could not be terminated, efficient relief could not be raised—there was no help then—so the unemployed underwent their destiny: ate the bread and drank the waters of affliction.

Misery generates hate. These sufferers hated the machines which they believed took their bread from them. They hated the buildings which contained those machines. They hated the manufacturers who owned those buildings. In the parish of Briarfield, with which we have at present to do, Hollow’s Mill was the place held most abominable, Gérard Moore, in his double character of semiforeigner and thoroughgoing progressist, the man most abominated. And it perhaps rather agreed with Moore’s temperament than otherwise to be generally hated, especially when he believed the thing for which he was hated a right and an expedient thing, and it was with a sense of warlike excitement he, on this night, sat in his countinghouse waiting the arrival of his frame-laden wagons.

The night was still, dark, and stagnant. The water yet rushed on full and fast. Its flow almost seemed a flood in the utter silence. Moore’s ear, however, caught another sound—very distant but yet dissimilar—broken and rugged—in short, a sound of heavy wheels crunching a stony road. He returned to the countinghouse and lit a lantern, with which he walked down the mill yard and proceeded to open the gates. The big wagons were coming on. The dray horses’ huge hooves were heard splashing in the mud and water. Moore hailed them: “Hey, Joe Scott! Is all right?”

Probably Joe Scott was yet at too great a distance to hear the inquiry; he did not answer it.

“Is all right? I say,” again asked Moore, when the elephant-like leader’s nose almost touched his.

Someone jumped out from the foremost wagon into the road. A voice cried aloud: “Ay, ay, divil, all’s raight. We’ve smashed ’em.”

And there was a run. The wagons stood still; they were now deserted.

“Joe Scott!” No Joe Scott answered. “Murgatroyd! Pighills! Sykes!” No reply. Mr. Moore lifted his lantern and looked into the vehicles. There was neither man nor machinery; they were empty and abandoned.

Now, Mr. Moore loved his machinery. He had risked the last of his capital on the purchase of these frames and shears which tonight had been expected. Speculations most important to his interests depended on the results to be wrought by them. Where were they?

The words We’ve smashed ’em! rang in his ears. How did the catastrophe affect him? By the light of the lantern he held, his features were visible, relaxing to a singular smile—the smile the man of determined spirit wears when he reaches a juncture in his life where this determined spirit is to feel a demand on its strength, when the strain is to be made and the faculty must bear or break. Yet he remained silent, and even motionless, for at the instant he neither knew what to say nor do. He placed the lantern on the ground and stood with his arms folded, gazing down and reflecting.

New Invented Elastic Breeches, by Thomas Rowlandson, c. 1812. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Elisha Whittelsey Collection, Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 1959.

An impatient trampling of one of the horses made him presently look up. His eye in the moment caught the gleam of something white attached to a part of the harness. Examined by the light of the lantern, this proved to be a folded paper—a billet. It bore no address without; within was the superscription: “To the Divil of Hollow’s Miln.”

We will not copy the rest of the orthography, which was very peculiar, but translate it into legible English. It ran thus: “Your hellish machinery is shivered to smash on Stilbro’ Moor, and your men are lying bound hand and foot in a ditch by the roadside. Take this as a warning from men that are starving and have starving wives and children to go home to when they have done this deed. If you get new machines, or if you otherwise go on as you have done, you shall hear from us again. Beware!”

Charlotte Brontë

From Shirley. Soon after Brontë began work on this novel, set during the Luddite uprisings of 1812, she laid it aside when her brother and two remaining sisters died within months of one another. “Had a prophet warned me how I should stand in June 1849,” she later wrote, “I should have thought—this can never be endured.” In May 1851 she traveled to London, where she attended a lecture by William Makepeace Thackeray and visited the Great Exhibition’s Crystal Palace. “It was very fine, gorgeous, animated, bewildering,” she wrote in a letter to a friend, “but I liked Thackeray’s lecture better.”