Past the break in the reef, wide banks of coral shelve off, creating the bar where the waves muster for the onset, thundering in water bolts that shake the whole reef till its very spray trembles. And then is it that the swimmers of Ohonoo most delight to gambol in the surf.

For this sport a surfboard is indispensable, some five feet in length, the width of a man’s body, convex on both sides, highly polished, and rounded at the ends. It is held in high estimation, invariably oiled after use, and hung up conspicuously in the dwelling of the owner.

Ranged on the beach, the bathers by hundreds dash in and, diving under the swells, make straight for the outer sea, pausing not till the comparatively smooth expanse beyond has been gained. Here, throwing themselves upon their boards, tranquilly they wait for a billow that suits. Snatching them up, it hurries them landward, volume and speed both increasing till it races along a watery wall like the smooth, awful verge of Niagara. Hanging over this scroll, looking down from it as from a precipice, the bathers halloo, every limb in motion to preserve their place on the very crest of the wave. Should they fall behind, the squadrons that follow would whelm them; dismounted and thrown forward, as certainly would they be run over the steed they ride. ’Tis like charging at the head of cavalry; you must on.

An expert swimmer shifts his position on his plank, now half striding it and anon, like a rider in the ring, poising himself upright in the scud, coming on like a man in the air.

At last all is lost in scud and vapor, as the overgrown billow bursts like a bomb. Adroitly emerging, the swimmers thread their way out and, like seals at the Orkneys, stand dripping upon the shore.

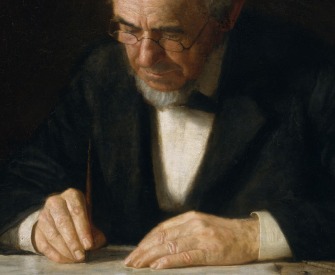

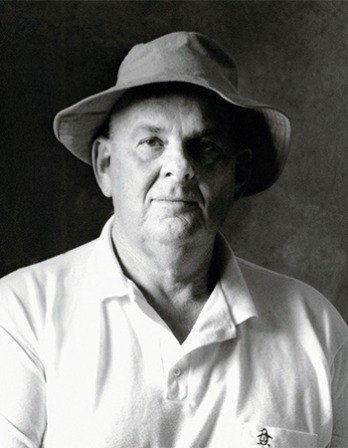

From Mardi. Melville followed his first two successful adventure novels, Typee and Omoo, with this allegorical and fantastical work about a man on a quest to find “all beauty and innocence.” The critics found it incomprehensible, and the author turned to reading works by Shakespeare with “eyes which are as tender as young sparrows.” Two years later in 1851, he published Moby-Dick.

Back to Issue