On December 2, 1964, during a sit-in on the UC Berkeley campus—an event that led to the arrest of nearly eight hundred demonstrators and a student strike that shut down the university—Mario Savio, the most visible speaker of the Free Speech Movement, gave a talk he called “An End to History.” “The university,” he said, “is the place where people begin seriously to question the conditions of their existence and raise the issue of whether they can be committed to the society they have been born into. After a long period of apathy during the fifties, students have begun not only to question but, having arrived at answers, to act on those answers. This is part of a growing understanding among many people in America that history has not ended, that a better society is possible, and that it is worth dying for.”

Alice Waters, then a twenty-year-old sophomore from New Jersey recently transferred to Berkeley, took Savio at his word. Seven years later, on August 28, 1971, she opened the restaurant Chez Panisse in the first-floor front room of an old, two-story, semi-Victorian house on Shattuck Avenue between Cedar and Vine. Named for Honoré Panisse, one of the riot of characters in and about the Marseilles waterfront in Marcel Pagnol’s 1930s Fanny trilogy, it was invested in the notion that history is improvisation, that a sense of the good life and how to make it rises from food on a plate.

My wife and I were there on opening night; we were booked for the second seating, arrived about nine, and sat down at a big table already occupied by a host of friends. Out of the swinging kitchen doors came two pâtés, and then, with perfect timing, plates of duck. “This is something!” we said. “To have it down like clockwork, and on the first night!” Then we noticed that no one else at the table looked as pleased as we did. “You just got here,” one person said, almost accusingly. “We’ve been waiting here since six. This,” she said, pointing at the duck before her, as if it were as cold as her appetite, “is the first we’ve seen of this.”

Within the time it took to take a bite and then realize one had to have another, the mood changed and then became noticeable elsewhere in the room as people at other tables were overtaken by the same feeling of surprise at how good something could taste. The way a peach or even a green salad could taste so fully of itself, as if it were both a thing and the idea of it, was suggesting that other parts of life, outside the restaurant, could achieve the same rightness.

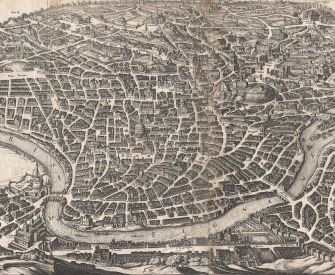

The Land of Cockaigne, by Pieter Bruegel the Elder, 1567. Alte Pinakothek, Munich.

I was teaching at Berkeley at the time; students had come there because that, they thought, was where was history was being made. I remember them looking around the dulled campus, and I almost wish I didn’t remember the looks on their faces when they asked me why it was that they had arrived too late—or, worse, if they had somehow been born too late. But here at Alice’s restaurant was a place where the spark of Mario Savio’s speech could still be found. Over the next weeks and months, it became the gathering place to which people kept coming back, as if to a well. It happened in fits and starts. “It wasn’t until the next week that the food really took hold,” says a woman who had shopped with Alice for dishware the week before the restaurant opened. At the very start, cooks and partners—Leslie Lande, Paul Aratow—came and went quickly, but the chefs, Victoria Kroyer, Barbara Rosenblum, and Lindsey Shere, the pastry chef, were finding their footing and also finding their way into the restaurant as Alice imagined it: that every dish was to be made to bring out the essence of what it was, that each serving of fish or chicken or asparagus or nectarines be made to orchestrate, to dramatize what it was, to give up its secret, that secret flavor, smell, texture, and even aura that, to the best knowledge and recollection of the people sitting down at Chez Panisse’s tables, had been hidden in plain sight or buried in the ground.

That is what people meant when they told their friends, There’s this place on Shattuck between Cedar and Vine—or, as the word spread, In Berkeley—or, as it spread farther, Near San Francisco, across the Bay—and whatever they put on the plate, it’s like you never tasted it before. Starting with what appeared on a plate—a stew of wild mushrooms, a few lettuces with yellow and orange flowers, a baked garlic, an almond tart—the idea that things could be better than one had expected—that your life, your town, your state, or your country could be better than you had believed it could be—began to seem not merely obvious, but necessary.

In the little country Chez Panisse was making, it was a time of continual experiment, ferment, and surprise. Every night the restaurant assembled a different menu, with four or five courses: you came for what Alice and the kitchen decided to do. You don’t show up at someone’s house expecting to choose between chicken or fish, beets or tomatoes; you expect the cook to do his or her best to dazzle you, to outdo her- or himself, and that was the idea at Chez Panisse, too. People learned quickly that the way to join the community of the place was not to go for what you thought you’d like but for what you thought you wouldn’t. With the burden of choice lifted, people were paradoxically more free to enjoy what was placed before them—and the atmosphere was such, with cooks and waiters communicating a sense of risk, play, and anticipation, that if something didn’t work it didn’t turn into a must to avoid. It was an invitation to make sure you didn’t miss it the next time it appeared, when it would be right.

The freshness of the ingredients, the sparkle of flavors in the mouth, the way a plate could be so visually balanced and yet seem uncomposed—each of these elements was, night by night, a surprise in and of itself, so that neither the customers in the dining room nor the cooks behind the kitchen doors took anything for granted.

It was often said in 1964, as the Free Speech Movement unfolded, that those who took part in a revolt against their own institutions would someday be running them; it hadn’t worked out that way. Instead, some people were trying to run their own small, local, self-sustaining institutions. It could be a school. It could be a farm. It could be a magazine, a record label, a design shop, a computer factory in a garage, a film festival. It could be a restaurant.

© 2011 by Greil Marcus. Used with permission of the author.

From “Chez Panisse.” After graduating from UC Berkeley in 1967, Waters worked as a waiter at a restaurant called The Quest and as a teacher at a Montessori school. In 1971 she received ten thousand dollars from her parents to open Chez Panisse, a restaurant that kept long hours and bought local food. A music journalist and cultural critic, Marcus published When That Rough God Goes Riding in 2010.

Back to Issue