The sea hath fish for every man.

—William Camden, 1605A Watery Funeral

Jules Verne bids farewell to a friend.

Captain Nemo conducted me to the poop of the Nautilus, and escorted me into a cabin situated near the sailors’ quarters.

There, on a bed, lay a man about forty years of age, with a resolute expression of countenance, a true type of Anglo-Saxon.

I leaned over him. He was not only ill, he was wounded. His head, swathed in bandages covered with blood, lay on a pillow. I undid the bandages, and the wounded man looked at me with his large eyes and gave no sign of pain as I did it. The skull, shattered by some deadly weapon, left the brain exposed, which was much injured. Clots of blood had formed in the bruised and broken mass, in color like the dregs of wine.

“What caused this wound?” I asked.

“What does it signify?” he replied evasively. “A shock has broken one of the levers of the engine, which struck him. But your opinion as to his state?”

I hesitated before giving it.

“You may speak,” said the captain. “This man does not understand French.”

I gave a last look at the wounded man.

“He will be dead in two hours.”

“Can nothing save him?”

“Nothing.”

Captain Nemo’s hand contracted; tears glistened in his eyes, which I thought incapable of shedding any.

For some moments I still watched the dying man, whose life ebbed slowly. His pallor increased under the electric light that was shed over his deathbed. I looked at his intelligent forehead, furrowed with premature wrinkles, produced probably by misfortune and sorrow. I tried to learn the secret of his life from the last words that escaped his lips.

Slavers Throwing Overboard the Dead and Dying, Typhoon Coming On, by J. M. W. Turner, 1840. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Henry Lillie Pierce Fund.

“You can go now, M. Aronnax,” the captain told me.

The next morning I went onto the bridge. Captain Nemo was there before me. As soon as he perceived me, he came to me.

“Professor, will it be convenient to you to make a submarine excursion today?”

“With my companions?” I asked.

“If they like.”

“We obey your orders, captain.”

I rejoined Ned Land, the prince of harpooners, and my assistant Conseil, and told them of Captain Nemo’s proposition. Conseil hastened to accept it, and Land seemed quite willing to follow our example.

It was eight o’clock in the morning. At half past eight we were equipped with diving suits for this new excursion and provided with two contrivances for light and breathing. The double door was open, and, accompanied by Captain Nemo, who was followed by a dozen of the crew, we set foot, at a depth of about thirty feet, on the solid bottom on which the Nautilus rested.

A slight declivity ended in an uneven bottom, at fifteen fathoms depth. This bottom differed entirely from the one I had visited on my first excursion under the waters of the Pacific Ocean. Here, there was no fine sand, no submarine prairies, no sea forest. But I immediately recognized that marvelous region, the coral kingdom.

The light produced a thousand charming varieties, playing in the midst of the branches that were so vividly colored. I seemed to see the membranous and cylindrical tubes tremble beneath the undulation of the waters. I was tempted to gather their fresh petals, ornamented with delicate tentacles, some just blown, the others budding, while small fish, swimming swiftly, touched them slightly like flights of birds. But if my hand approached these living flowers, these animated sensitive plants, the whole colony took alarm. The white petals reentered their red cases, the flowers faded as I looked, and the bush changed into a block of stony knobs.

Chance had thrown me just by the most precious specimens of this zoophyte. This coral was more valuable than that found in the Mediterranean, on the coasts of France, Italy, and Barbary. Its tints justified the poetical names of “Flower of Blood” and “Froth of Blood” that trade has given to its most beautiful productions. Coral is sold for twenty pounds per ounce, and in this place the watery beds would make the fortunes of a company of coral divers. This precious matter, often confounded with other polyps, formed then the inextricable plots called “macciota,” and on which I noticed several beautiful specimens of pink coral.

But soon the bushes contracted, and the arborizations increased. Real petrified thickets, long joists of fantastic architecture, were disclosed before us. Captain Nemo placed himself under a dark gallery, where by a slight declivity we reached a depth of one hundred yards. The light from our lamps produced sometimes magical effects, following the rough outlines of the natural arches, and pendants disposed like lusters, that were tipped with points of fire. Between the coralline shrubs I noticed other polyps not less curious—melites and irises with articulated ramifications; also some tufts of coral, some green, others red, like seaweed encrusted in their calcareous salts that naturalists, after long discussion, have definitely classed in the vegetable kingdom. But following the remark of a thinking man, “There is perhaps the real point where life rises obscurely from the sleep of a stone, without detaching itself from the rough point of departure.”

At last, after walking two hours, we had attained a depth of about three hundred yards, that is to say, the extreme limit on which coral begins to form. But there was no isolated bush, nor modest brushwood, at the bottom of lofty trees. It was an immense forest of large mineral vegetations, enormous petrified trees, united by garlands of elegant plumerias, and sea bindweed, all adorned with clouds and reflections. We passed freely under their high branches, lost in the shade of the waves, while at our feet, tubipores, meandrines, stars, fungi, and caryophyllidae formed a carpet of flowers sown with dazzling gems. What an indescribable spectacle!

Captain Nemo had stopped. My companions and I halted, and turning, I saw his men were forming a semicircle around their chief. Watching attentively, I observed that four of them carried on their shoulders an object of an oblong shape.

We occupied in this place the center of a vast glade surrounded by the lofty foliage of the submarine forest. Our lamps threw over the place a sort of clear twilight that singularly elongated the shadows on the ground. At the end of the glade the darkness increased, and was only relieved by the little sparks reflected by the points of coral.

Ned and Conseil were near me. We watched and I thought I was going to witness a strange scene. On observing the ground, I saw that it was raised in places by slight excrescences incrusted with limy deposits, and disposed with a regularity that betrayed the hand of man.

On the Beach, Boulogne-sur-Mer, by Édouard Manet, c. 1869. Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, Richmond, Collection of Mr. and Mrs. Paul Mellon.

In the midst of the glade, on a pedestal of rocks roughly piled up, stood a cross of coral that extended its long arms that one might have imagined were made of petrified blood.

Upon a sign from Captain Nemo, one of the men advanced, and at some feet from the cross, he began to dig a hole with a pickaxe that he took from his belt. I understood all! This glade was a cemetery, this hole a tomb, this oblong object the body of the man who had died in the night. The captain and his men had come to bury their companion in this general resting place, at the bottom of this inaccessible ocean!

The grave was being dug slowly; the fish fled on all sides while the retreat was being thus disturbed; I heard the strokes of the pickaxe, which sparkled when it hit upon some flint lost at the bottom of the waters. The hole was soon large and deep enough to receive the body. Then the bearers approached; the body, enveloped in a tissue of white byssus, was lowered into the damp grave. Captain Nemo, with his arms crossed on his breast, and all the friends of him who had loved them, knelt in prayer.

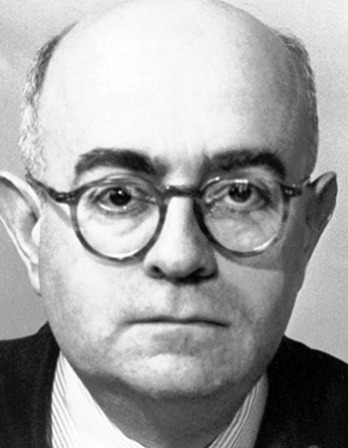

Jules Verne

From Twenty Thousand Leagues Under the Sea. Verne as a boy in the 1830s liked to study the harbor in his hometown of Nantes and the machines at a factory near his country house in Chantenay. “I have still as much pleasure in watching a steam engine or a fine locomotive at work,” he reflected later in life, “as I have in contemplating a picture by Raphael or Correggio.” As part of his Extraordinary Voyages series, he wrote, among other works, Journey to the Center of the Earth and Around the World in Eighty Days.