Usually speaking, the worst-bred person in company is a young traveler just returned from abroad.

—Jonathan Swift, 1730

Coast of Jamaica, by Martin Johnson Heade, 1874. Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, gift of Mrs. Katharine H. Putnam and the John Pickering Lyman Collection, by exchange, in memory of Maxim Karolik.

In the passport photo, the nineteen-year-old Jamaican girl stares straight ahead at the camera. Hers is a poker face. She has never blinked, and will not, especially now, ahead of her departure for a new life in New York. Her face does not betray her excitement. An aunt in Harlem has promised to sponsor her. But something goes wrong; the trip is canceled in the fallout from a vengeful family feud. The girl in the photo, Ethlyn, is my mother. She will give birth to me fifteen years later in Luton, an industrial town in the UK.

Ethlyn rarely spoke about the missed opportunity of becoming an American. The venture to the UK a decade later was something of a consolation prize. And yet there’s a look of resignation in her young eyes—as if she foresaw in 1952 that Luton rather than Harlem would be her eventual destination. That year was a turning point in family lore. A July 2, 1952, article in the Gleaner, Jamaica’s national newspaper, reported a new quota system restricting any future attempt at joining relatives in Harlem: “About 25,000 Jamaicans on the waiting list of the American Consulate General for immigration visas to enter the United States now face very dim prospects as a result of the McCarran Bill.”

The bill favored migrants of northern European descent, rewarding those from regions that had longer traditions of unforced migration to the United States. Immigration quotas were imposed on the British colonies in the Caribbean but not Western European countries. New York congressman Adam Clayton Powell Jr. was among the critics who believed the bill was expressly intended to limit the migration of black people into the United States. “This bill makes this no longer a land of the free,” he said, “but a place only for Anglo-Saxons.” Those of our family members who made it to the U.S. before the gates closed supposedly thrived, at least financially, while those who missed the boat to the U.S. (as it were) and wound up in the UK were pitied as the poor relations.

My family tree has only a few recorded branches. Before Ethlyn, who was born in Jamaica in 1932, there was her mother, Pauline Fredrickson, a dancer, billed “Late of New York” when she returned to Jamaica in the 1920s to perform with the Butterfly Troupe. Pauline’s mother, Theresa, was a violinist who, according to family legend, once played at Carnegie Hall and gave birth as a teenager to Pauline. Then there was Great Granny Reid, who’d run a bar in Panama City for workers building the Panama Canal. Even more glamorous was Aunt Anita, who had held up a bank in the U.S., fled across the border to Canada, was tracked down by a mounted policeman, flirted with him, avoided arrest, and eventually married him. And before Aunt Anita, there was Gong, my great-great-great-great-great-grandmother, who was abducted from Africa and enslaved in Jamaica. And that’s it—in our family we can go back no further. The rest is darkness. (My father never spoke about his family—not one word.) Outside of Gong, what marks all the branches and generations is a kind of restlessness, manifested in migration.

Migrating blue wildebeest. Photograph by Neveu P. © Horizonfeatures / Bridgeman Images.

Today almost as many Caribbeans reside overseas than live at home. Outward and inward migration from and to the region provides an illuminating case study into the pattern and history of migration. Immigrant has become a dirty word, a term of abuse. But Caribbean pioneers have been, and continue to be, a great expeditionary force that keeps the world turning.

People have always been on the move, all the more when travel became easier. On one level, the world can be divided into those who leave their birthplace and those who remain. “To be born on a small island, a colonial backwater,” wrote Derek Walcott, “meant a precocious resignation to fate.” The only protest was to get away. When Ethlyn and my father, Bageye, left in 1959, they did so in the midst of what was coined “England fever.” If you had youth, energy, chutzpah, and a bit of money, you took a chance and boarded a ship or plane. So many were leaving that a joke soon circulated the islands: “Will the last one out please turn off all the lights?”

In Britain and elsewhere, the great story of West Indian migration has focused on the so-called Windrush generation, associated with the arrival of close to a thousand people on board the HMT Empire Windrush in 1948. Though cast as a foundational story, primarily because it was captured on film and reported widely in newspapers, the ship’s arrival was just one of many in the late 1940s. In 1947, for instance, the Ormonde and the Almanzora preceded the Windrush, bringing more than five hundred migrants without any fanfare. As citizens of the British Empire, colonial subjects were entitled to work and settle in Britain. Encouraged to come and help rebuild the country after the ravages of World War II, West Indians did so in the hundreds of thousands—at least until Parliament passed the Commonwealth Immigrants Act in 1962, restricting entry to those with work permits.

The Windrush drama is matched by earlier, even more seminal stories of West Indian migration to Central America. Migrants undertake risks for the promise of a good outcome. The West Indians who made up two-thirds of the workforce that built the Panama Canal, sacrificing lives, limbs, and mental health, were dying to better themselves. The tales of those who perished, choked in mudslides or blown apart in explosions, were often eclipsed by the transformation of impoverished workers into “Colón men” returning home with a swagger, a gold watch on a chain in their waistcoat, a fedora atop their heads, and entertaining tales. And then it stopped. At two pm on October 10, 1913, President Woodrow Wilson pushed a button in Washington, DC, transmitting a telegraphic message that signaled a massive explosion almost two thousand miles away, cutting into the earth and sending up a huge surge of water. It marked the final stage of the construction of the canal, which would open the following year. It was time for tens of thousands of itinerant workers and migrants to move on. They included my great-great-uncle Herbert Reid, who, aged twenty, sailed from Cristobal, Panama, to New York City in 1916.

“Wheel and come again” is how Ethlyn once described this circular migration, back and forth from the island, from somewhere to elsewhere, to turn around and start all over again. From emancipation onward, the West Indies was a region you left, if not permanently, then at least seasonally—for work in the States, ideally.

Jamaica is just over five hundred miles from the North American coast. Often when told that someone you hoped to meet or phone in Jamaica is not around, you’ll hear that they are “off the island.” Generally, this means they’ve gone for the weekend to Miami to buy something, a fridge or television, or to visit family and friends. There are so many Jamaicans in Miami, islanders occasionally joke that it’s really Kingston 21, a local district. In the 1970s, when middle-class merchants complained loudly about the direction that the socialist prime minister Michael Manley was taking the country, he curtly reminded them, “Jamaica has no room for millionaires. For anyone who wants to be a millionaire, we have five flights a day to Miami.”

Manley’s chastisement echoed anxious notions of belonging and unbelonging, about where, if anywhere, Jamaicans call home. As the Rastas say, “Jamaica is an island but not I land.” Black Jamaicans are Africans in exile, they argue. This temporary, liminal state is an odd place to inhabit. It seems to have been one that accompanied my parents on their journey to Britain. As a child I recall how they routinely counseled us that we were “not to get too comfortable,” because we were “only passing through.”

But where to? Presumably back to Jamaica, but that never happened. It was as fanciful and unlikely as Marcus Garvey’s back-to-Africa scheme. Until you could replicate the comforts and potential of Harlem (in the case of Garvey’s followers) in Monrovia or the steady opportunities for advancement offered by Luton (in the case of our family and thousands of West Indians like us in the UK) in Kingston, then such romantic notions of return were never going to be realized.

Several of my maternal uncles went to sea as merchant seamen. The second eldest, Victor, liked to take credit for saving the others from penury. Back in the 1940s and 1950s, jobs were not easy to come by on the islands. “You’d see the boys on a Monday morning wandering downtown with their briefcases full of diplomas,” recalls Ethlyn, “but there was no work.” Victor, who after a decade at sea with the shipping company the Royal Mail Steam Packet Company had been promoted to chief steward, put in a good word with his superiors, recommending his brothers for jobs, first as galley boys and later as stewards. “I wasn’t going to leave them behind, leave dem mash up,” he says. It was a good life and preparation for the eventual dream of leaving the island.

As a boy in Luton, I found their stories of life at sea too far removed from my reality to be conceivable. Added to the glamour was a complication. Alongside these joyful stories were pitiful accounts of family friends, young boys not much older than I was, who had gone to sea with less scrupulous employers than the RMSPC on unseaworthy vessels and, soon after signing on, had drowned. I conflated their watery graves with those ancestors who had gone before on the Middle Passage. A childhood book, whose title I no longer remember, conjured a disturbing image: so many Africans had died (either thrown overboard or by suicide) that their accumulated bones formed an undersea pathway from Africa to the Americas.

The Caribbean was the locale of a great catastrophe, a sprawling holding pen of five million Africans abducted during the Atlantic slave trade from the sixteenth century onward. It also gave birth to the modern world and its global economy and was among the world’s first multicultural societies. The archipelago was the site of destruction of indigenous populations, bringing together a crucible of Europeans (adventurers and shackled Cromwellian convicts alike), enslaved laborers abducted from Africa, and a dwindling number of Amerindians. Plantations were forced-labor camps, a brutal capitalist experiment that was further complicated after emancipation by the courtship and arrival of indentured workers from India, China, and elsewhere. The West Indies was the axis on which modernity turned, both fueling Europe’s industrial revolutions and providing a winner-takes-all blueprint for how small numbers of European outliers might live cheek by jowl with a majority-terrorized population. Rather than “Caribbean,” the new locals, made up of stolen Africans and voluntary and involuntary European migrants, might be described more accurately as “African Europeans,” writes the British Guiana–born educator Joyce Estelle Trotman.

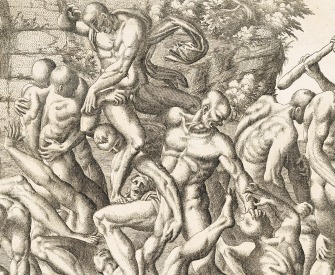

Israelites Crossing the Red Sea, by Cornelis Cornelisz Van Haarlem, 1594. Princeton University Art Museum, museum purchase, gift of George L. Craig Jr. and Mrs. Craig.

On a geopolitical level, voluntary migration is the result of one group of people, no matter their color, who move from an area where they have little cultural or economic capital to another where they hope their fortunes will improve. The Windrush generation, often cast as heralding mass immigration to the UK, did seek a better future in the country. What is not so readily told is that their arrival was also the result of mass outward migration. In 1947 Winston Churchill had implored the more than half a million “lively and active citizens in the prime of life” who had applied to immigrate to the Commonwealth countries perceived in the British public imagination as white—Australia, New Zealand, South Africa, Canada—not to desert Britain. “We cannot spare you!” he warned. But such pleas fell on deaf ears. In a sense, the 300,000 West Indians who arrived in the UK from the late 1940s to 1962 replaced more than a million white Britons who left during that same period. But when the Sri Lankan–born writer and intellectual Ambalavaner Sivanandan said, in answer to the vocal anti-immigrant sentiment at large in postcolonial Britain, “We are here because you were there,” he was referring to an earlier iteration of white British migration to the colonies.

In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, large numbers of British people, suffering hardships they seemed to have no choice but to endure, were cleared off what had been common land. England’s enclosures and the Highland clearances in Scotland were an existential threat to landless people, who had to leave in order to seek alternatives. The consequences should not have been unexpected: British migrants traveled to new territories, where they in turn forcibly plundered and drained the land of its wealth, replicating a system they had left behind.

Some of them became settlers, drivers, overseers, and managers on slave plantations in the West Indies. Newspapers described them as “sojourners” during Scotland’s “golden age of sugar,” a time, after the American War of Independence, when Scottish investors turned away from tobacco production and made fortunes from West Indian slave plantations growing sugarcane. Even the great poet of democracy Robert Burns contemplated a Faustian pact with slavery. In 1786, struggling to make a living as a farmer in Ayrshire, the bard accepted an offer of employment as a “Negro driver” on a sugar plantation in Jamaica. Burns booked his passage and was saved from emigration only by a sudden upturn in his success as a writer.

Migration can be seen as a great shuffling and reshuffling of people, places, and fortunes. Its end result is unresolved, and its bitter legacy lies just beneath the surface in places such as the Caribbean. The end of slavery in the British Empire was propelled by a £20 million compensation scheme (the equivalent of £2.4 billion today) that the government offered not to the enslaved but to the slaveholders in 1834. When I asked Louise Smith, an octogenarian Jamaican who has been living in the UK since the 1950s, why she had migrated, she reminded me that the social and racial strata of Jamaica in her youth was rooted in slavery, a pigmentocracy that favored white people: “They is on the level part; they capture it, they have the better part in Jamaica. We is up in the hills where goat run; they, the white man, on the level.”

To many visitors the former colonies of the British West Indies appear an enigma. Put the white British colonizers to one side. How to explain the Sephardic Jewish synagogues, the Chinese dragon dancers, the Ramlila performance of the Hindu epic the Ramayana, the German settlement in Jamaica, the Lebanese seamstresses? Again, the transatlantic slave trade holds the clues to these migrations.

At the end of slavery, the formerly enslaved refused to work on plantations, and the planters panicked, fearing ruin now that the emancipated black man was allegedly content to sit in the shade under a tree spitting out seeds from a watermelon while the sugarcane rotted. They looked abroad for laborers. Chinese people and Indians in particular were considered prime candidates, and recruiting depots were established in Hong Kong. In the following decades, tens of thousands of Indians were brought to Jamaica, British Guiana, Trinidad, and elsewhere in the Caribbean, usually men on five-year indentureships. On arrival they were given agricultural tools, cooking utensils, and a suit of clothing and were quickly dispatched to plantations on mule carts or freight trains. Their terms of work were not favorable. In Jamaica, only once their indentureships came to an end could these so-called time-expired Indians obtain freedom passes, enabling them access to any part of the island. They still had to remain in the country for two more years before they could apply for repatriation. By the 1870s, though, the authorities were offering inducements for them to remain. The most attractive reward was a grant scheme providing up to twelve acres of Crown land, but often it was worthless, located in infertile mountainous regions.

Some Chinese migrants found themselves in the West Indies following tragic circumstances. The Panama connection to the West Indies predated the canal, with the construction of the Panama Railroad from 1850 through 1855. According to a 1963 children’s history of the Panama Canal by Paul Rink, the “cheerful and humble” West Indians were deemed best suited to the conditions, as they were “slow-moving, accustomed to heat, resistant to the fevers.” The annual average workforce numbered six thousand, but the railroad company did not keep reliable statistics of deaths. The writer Robert Tomes visited the area and reported that the death toll was one in forty West Indians. By 1854 the West Indians were working alongside a thousand-strong Chinese workforce whose even higher death toll—Tomes was informed that their mortality rate was one in ten, though other estimates suggest up to two-thirds of them died from the dangerous work, disease, or suicide—spawned the legend of “a Chinaman buried underneath every cross tie.” Survivors, packed onto a return ship to Hong Kong, were so unwell that their journey was cut short, and they had to stop and disembark in Jamaica. There they joined another group of Chinese workers who had arrived in August of the previous year on board The Epsom, after more than a hundred days at sea; they had been contracted as indentured laborers for sugar, coffee, and pimento estates. Within two generations Chinese Jamaicans became embedded in Jamaican society, having transformed themselves into businessmen running a raft of establishments from grocery stores, bakeries, and haberdasheries to betting shops and later, with the rise of reggae, record shops and record companies. Yet every few decades, a virulent anti-Chinese strain seemed to break out among the black population.

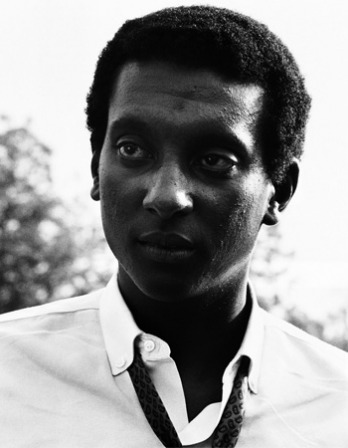

Let us leave this Europe which never stops talking of Man yet massacres him at every one of its street corners, at every corner of the world.

—Frantz Fanon, 1961Scapegoating of the latest migrants to arrive, no matter their origin, seems to have occurred throughout the region. In 1962 V.S. Naipaul recounted the antipathy toward Grenadian immigrants when he returned to Trinidad: “The attitudes to immigrants are the same the world over—the stories about West Indians in England (‘twenty-four to a room’) are exactly matched by the stories about Grenadians and others in Trinidad.”

The difference between the newcomers and the natives had nothing to do with race and everything to do with migration, ambition, and a responsibility to those who had invested in them. Travel was often expensive, and those fortunate enough to leave home often did by borrowing money from relatives, who needed to be repaid. The same entrepreneurial spirit evident in the Chinese in Jamaica was also found among West Indian migrants to the U.S. at the turn of the twentieth century. It led West Indians to open tailor shops, restaurants, real estate companies, and more in black American communities. Later, in the 1930s, Federal Writers Project researchers recorded the received opinion that “if a West Indian has ten cents above a beggar, he opens a business.” Sometimes these immigrants were resented for their overt displays of an imagined superiority and for their continued allegiance to Britain, not America. The Jamaican author Claude McKay recalled that they were “incredibly addicted to the waving of the Union Jack in the face of their American cousins.”

These West Indians were not in Luton but in Harlem, Brooklyn, and Miami for a reason. The United States was geographically closer, and although many black people were still living under Jim Crow restrictions, West Indians still found North America easier to navigate culturally and economically, with greater potential for social mobilization, than the UK. It was also perceived to be richer and far more glamorous. “When I was growing up in Jamaica in the 1950s,” says the writer Viv Adams, “English cars were seen as kind of dinky toys, lacking in glamour. When a man made it, he would drive an American car.”

The contrast between potentialities can be seen in the ascent of Colin Powell, the late four-star general and former U.S. secretary of state. In 1995 the Times asked its readers to carry out a mental exercise: strip Colin Powell from his immaculate military uniform and dress him instead in a London bus driver’s gray drab and put him on board a red double decker, shouting, “Fares please.” It sounded fanciful, but the description matched his cousin Mervin, whose side of the family had migrated to Britain.

Migration may be good for material wealth, but can the same be said for mental health? Psychiatrists have long concluded that the dislocation and dissonance of migration, whether internal (within a country) or external (from one country to another), has a negative effect on immigrants that can even extend to their children. The prevalence of schizophrenia among young black boys born in the UK to West Indian parents has consistently been shown to be significantly higher than among the general population. Growing up in Luton in the 1970s, hearing accounts of black British children being sent back to the Caribbean by their parents, I asked my mother what was going on. “England mad them,” she said drily.

That trauma was also evident among the plight of the so-called barrel children, who had been left behind by parents migrating to either North America or the UK and put in the care of grandparents or members of their extended families. Their parents could not afford to bring them and planned to send for them later, after settling in. Sometimes that took up to ten years. In the meantime, parents in Toronto, Harlem, and London would send barrels of clothes and toys to their children back home twice a year. When the time came for the children to leave and join their parents, the caring grandparents and relatives faced great trauma in parting with children, who then often had difficulty bonding with their own parents. “My mother didn’t accept me,” recalls Everine Shand, who left Jamaica in 1960 to be reunited with her mother in UK after several years apart. “She had no maternal instincts. I don’t even remember her hugging me when she saw me at the airport.”

West Indian migrants made the clearheaded calculation of sacrificing emotional health for financial gain. There may have been regrets along the way, but largely they pulled up the collars on their coats and walked on. Always, though, there was the longing in the heart that could not be conquered: the dream of return. When a dyspeptic V.S. Naipaul returned to Trinidad and found people who looked just like him, he saw “a peasant-minded, money-minded community, spiritually static [and] cut off from its roots.” He failed to see the irony of bemoaning the Trinidad “Indians who went to India [and] returned disgusted by the poverty and convinced of their own superiority.” Naipaul’s depiction of spiritually depleted Trinidadian Indians contrasts with a tale from the 1970s told to me by Shirley Williams, a Guyanese-born former nurse, about the elderly Indo-Guyanese who eagerly lined up to board a ship that the government had arranged to ferry them back to India (complete with a pharmacist, Shirley’s father) so that they might return home in time to die.

That same sentiment was echoed by the West Indians I grew up with in Luton. At funerals you’d hear them complain, “Bwoi, dis country too cold for bury.” Perhaps it was the same notion that finally convinced Ethlyn to go back to Jamaica for a recon before a permanent return, after an absence of more than thirty years.

I accompanied my mother, and it was painful and joyous to see what had been lost by her departure all those years ago. The transformation, evident as soon as we touched down at Kingston airport, was remarkable. My mother was very excited, yet more relaxed in her body than I’d ever seen her. She joked continually with local people. She sang merrily all the time, in contrast to the plaintive hymns I heard from her in our 1960s Luton home; she even recalled and sang a childhood song about the general penitentiary when we passed it. I was awed.

Growing up in Luton, I’d always felt my mother was constrained by Britain’s gray, forbidding culture. She had the migrant’s nervousness of not wishing to draw attention to her otherness. There it was as if she were an artist drawing on only a few dull colors; here in Jamaica, she had a whole rainbow palette. And I thought: What if, what if she had stayed? Would that nineteen-year-old girl from the passport photo have been just as vibrant throughout the intervening years as she was now, closer to retirement age? We spent long periods looking over the island as Ethlyn refamiliarized herself with her birthplace. By the time we returned to the airport two weeks later, my mother had made up her mind. “I’ll occasionally come back and reside in the UK,” she said. “But as for living? I’ll live, really live, in Jamaica. I’m coming home.”