It was down on the shore, tramping along the pebbled terraces of the beach, clambering over the great blocks of fallen conglomerate which broke the white curve with rufous promontories that jutted into the sea, or, finally, bending over those shallow tidal pools in the limestone rocks which were our proper hunting ground—it was in such circumstances as these that my father became most easy, most happy, most human.

That hard look across his brows, which it wearied me to see, the look that came from sleepless anxiety of conscience, faded away and left the dark countenance still always stern indeed, but serene and unupbraiding. Those pools were our mirrors in which, reflected in the dark hyaline and framed by the sleek and shining fronds of oarweed, there used to appear the shapes of a middle-aged man and a funny little boy, equally eager and, I almost find the presumption to say, equally well prepared for business.

If anyone goes down to those shores now, if man or boy seeks to follow in our traces, let him realize at once, before he takes the trouble to roll up his sleeves, that his zeal will end in labor lost. There is nothing now, where in our days there was so much. Then, the rocks between tide and tide were submarine gardens of a beauty that seemed often to be fabulous, and was positively delusive, since, if we delicately lifted the weed curtains of a windless pool, though we might for a moment see its sides and floor paved with living blossoms, ivory-white, rosy-red, orange, and amethyst, yet all that panoply would melt away, furled into the hollow rock, if we so much as dropped a pebble in to disturb the magic dream.

Half a century ago, in many parts of the coast of Devonshire and Cornwall, where the limestone at the water’s edge is wrought into crevices and hollows, the tideline was, like John Keats’ Grecian vase, “a still unravished bride of quietness.” These cups and basins were always full whether the tide was high or low, and the only way in which they were affected was that twice in twenty-four hours they were replenished by cold streams from the great sea, and then twice were left brimming to be vivified by the temperate movement of the upper air. They were living flower beds, so exquisite in their perfection that my father used not seldom to pause before he began to rifle them, ejaculating that it was indeed a pity to disturb such congregated beauty. The antiquity of these rock pools and the infinite succession of the soft and radiant forms—sea anemones, seaweeds, shells, fish—which had inhabited them undisturbed since the creation of the world used to occupy my father’s fancy. We burst in, he used to say, where no one had ever thought of intruding before, and if the Garden of Eden had been situated in Devonshire, Adam and Eve, stepping lightly down to bathe in the rainbow-colored spray, would have seen the identical sights that we now saw—the great prawns gliding like transparent launches, anthea waving in the twilight its thick white waxen tentacles, and the fronds of the dulse faintly streaming on the water like huge red banners in some reverted atmosphere.

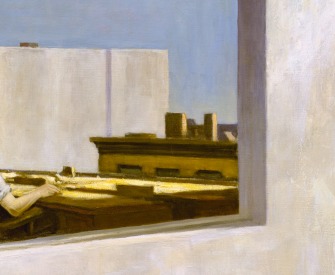

Sightseeing, by Maria Passarotti. 2007. C-print from negative. © Maria Passarotti, courtesy the artist.

All this is long over. The ring of living beauty drawn about our shores was a very thin and fragile one. It had existed all those centuries solely in consequence of the indifference, the blissful ignorance of man. These rock basins, fringed by corallines, filled with still water almost as pellucid as the upper air itself, thronged with beautiful sensitive forms of life—they exist no longer, they are all profaned and emptied and vulgarized. An army of “collectors” has passed over them, and ravaged every corner of them. The fairy paradise has been violated, the exquisite product of centuries of natural selection has been crushed under the rough paw of well-meaning, idle-minded curiosity. That my father, himself so reverent, so conservative, had by the popularity of his books acquired the direct responsibility for a calamity that he had never anticipated, became clear enough to himself before many years had passed, and cost him great chagrin. No one will see again on the shore of England what I saw in my early childhood, the submarine vision of dark rocks, speckled and starred with an infinite variety of color, and streamed over by silken flags of royal crimson and purple.

From Father and Son. The author’s father, Philip Henry Gosse, published A Naturalist’s Sojourn in Jamaica in 1851 and two years later helped establish at Regent’s Park the first public aquarium. While working in the library of the British Museum in 1870, Edmund published his poems in the book Madrigals, Songs, and Sonnets; only twelve of the 140 printed copies sold, but the ones he gave out impressed Dante Gabriel Rossetti and Algernon Charles Swinburne. Gosse published a biography of the latter in 1917.

Back to Issue