Journalists belong in the gutter, because that is where the ruling classes throw their guilty secrets.

—Gerald Priestland, 1988For Better or Worse

Anthony Trollope speaks now instead of holding his peace.

That morning, Caldigate rode into the town, and as he put his horse up at the inn, he felt that the very ostler had heard the story.

As he walked along the street, it seemed to him that everyone he met knew all about it. His wife’s half brother, the lawyer Robert Bolton, would, of course, have heard it; but nevertheless he walked boldly into the attorney’s office. His fault at the time was in being too bold in manner, in carrying himself somewhat too erect, in assuming too much confidence in his eye and mouth. To act a part perfectly requires a consummate actor; and there are phases in life in which acting is absolutely demanded. A man cannot always be at his ease, but he should never seem to be discomfited. For petty troubles, the amount of acting necessary is so common that habit has made it almost natural. But when great sorrows come, it is hard not to show them—and harder still not to seem to hide them.

When he entered the private room, he found that his father-in-law, the old banker Nicholas Bolton, was there with his son. He shook hands, of course, with both of them, and then he stood a moment silent to hear how they would address him. But as they also were silent, he was compelled to speak. “I hope you got home all right, sir, yesterday; and Mrs. Bolton.”

The old man did not answer, but he turned his face around to his son.

“I hear that you had that man Crinkett out at Folking yesterday,” said Robert.

“He was there, certainly, to my sorrow,” said Caldigate.

“And another with him?”

“Yes, and another with him, whom I had also known at Nobble.”

“And they were brought in to breakfast?”

“Yes.”

“And they afterward declared that you had married a wife out there in the colony?”

“That also is true.”

“They have been with my father this morning.”

“I am very, very sorry, sir,” said Caldigate, turning to the old man, “that you should have been troubled in so disagreeable a business.”

“Now, Caldigate, I will tell you what we propose.” It was still the attorney who was speaking, for the old man had not as yet opened his mouth since his son-in-law had entered the room. “There can, I think, be no doubt that this woman intends to bring an accusation of bigamy against you.”

“She is threatening to do it. I think it very improbable that she will be fool enough to make the attempt.”

“From what I have heard, I feel sure that the attempt will be made. Depositions, in fact, will be made before the magistrates some day this week. Crinkett and the woman have been with the mayor this morning, and have been told the way in which they should proceed.” Caldigate, when he heard this, felt that he was trembling, but he looked into the speaker’s face without allowing his eyes to turn to the right or left. “I am not going to say anything now about the case itself. Indeed, as I know nothing, I can say nothing. You must provide yourself with a lawyer.”

“You will not act for me?”

“Certainly not. I must act for my sister. Now what I propose, and what her father proposes, is this—that Hester shall return to her home at Puritan Grange while this question is being decided.”

“Certainly not,” said Caldigate.

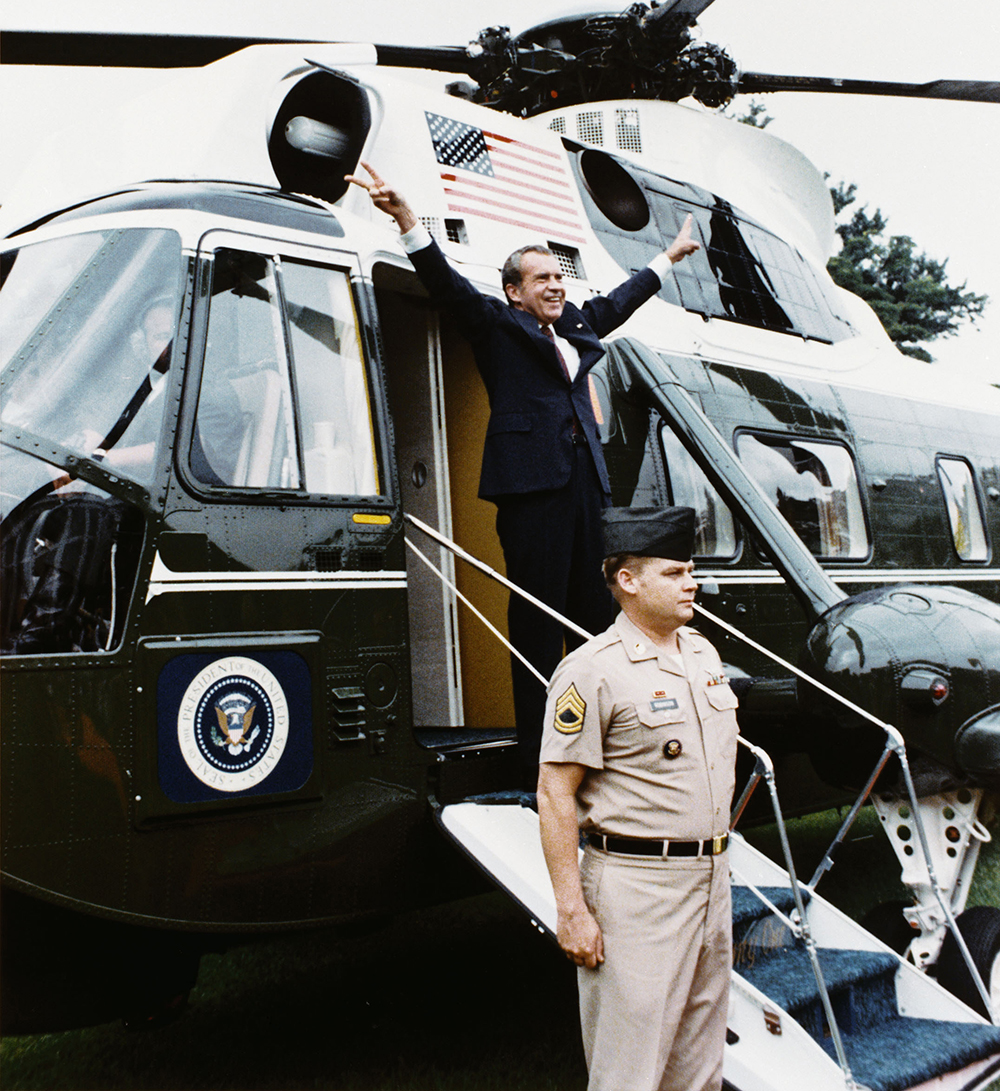

Richard Nixon departing the White House after resigning from the U.S. presidency, 1974. © The Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum.

“She must,” said the old man, speaking for the first time.

“We shall compel it,” said the attorney.

“Compel! How will you compel it? She is my wife.”

“That has to be proved. Public opinion will compel it, if nothing else. You cannot make a prisoner of her.”

“Oh, she shall go if she wishes it. You shall have free access to her. Bring her mother. Bring your carriage. She shall dispose of herself as she pleases. God forbid that I should keep her, though she be my wife, against her will.”

“I am sure she will do as her friends shall advise her when she hears the story,” said the attorney.

“She has heard the story. She knows it all. And I am sure that she will not stir a foot,” said the husband. “You know nothing about her.” This he said turning to his wife’s half brother; and then again he turned to the old man. “You, sir, no doubt, are well aware that she can be firm to her purpose. Nothing but death could take her away from me. If you were to carry her by force to Chesterton, she would return to Folking on foot before the day was over. She knows what it is to be a wife. I am not a bit afraid of her leaving me.” This he was able to say with a high spirit and an assured voice.

“It is quite out of the question that she should stay with you while this is going on.”

“Of course she must come away,” said the banker, not looking at the man whom he now hated as thoroughly as did his wife.

“Consult your own friends, and let her consult hers. They will all tell you so. Ask Mrs. Babington. Ask your own father.”

“I shall ask no one—but her.”

“Think what her position will be! All the world will at least doubt whether she be your wife or not.”

“There is one person who will not doubt—and that is herself.”

“Very good. If it be so, that will be a comfort to you, no doubt. But for her sake, while other people doubt, will it not be better that she should be with her father and mother? Look at it all around.”

“I think it would be better that she should be with me,” replied Caldigate.

“Even though your former marriage with that other woman were proved?”

“I will not presume that to be possible. Though a jury should so decide, their decision would be wrong. Such an error could not affect us. I will not think of such a thing.”

“And you do not perceive that her troubles will be lighter in her father’s house than in yours?”

“Certainly not. To be away from her own house would be such a trouble to her that she would not endure it unless restrained by force.”

“If you press her, she would go. Cannot you see that it would be better for her name?”

“Her name is my name,” he said, clenching his fist in his violence, “and my name is hers. She can have no good name distinct from me—no name at all. She is part and parcel of my very self, and under no circumstances will I consent that she shall be torn away from me. No word from any human being shall persuade me to it—unless it should come from herself.”

“We can make her,” said the old man.

“No doubt we could get an order from the court,” said the attorney, thinking that anything might be fairly said in such an emergency as this; “but it will be better that she should come of her own accord, or by his direction. Are you aware how probable it is that you may be in prison within a day or two?”

To this Caldigate made no answer, but turned around to leave the room. He paused a moment at the doorway to think whether another word or two might not be said in behalf of his wife. It seemed hard to him, or hard rather upon her, that all the wide-stretching solid support of her family should be taken away from her at such a crisis as the present. He knew their enmity to himself. He could understand both the old enmity and that which had now been newly engendered. Both the one and the other were natural. He had succeeded in getting the girl away from her parents in opposition to both father and mother. And now, almost within the first year of his marriage, she had been brought to this terrible misery by means of disreputable people with whom he had been closely connected! Was it not natural that Robert Bolton should turn against him? If Hester had been his sister, and there had come such an interloper, what would he have felt? Was it not his duty to be gentle and to give way, if by any giving way he could lessen the evil which he had occasioned. “I am sorry to have to leave your presence like this,” he said, turning back to Mr. Bolton.

“Why did you ever come into my presence?”

“What has been done is done. Even if I would give her back, I cannot. For better or for worse, she is mine. We cannot make it otherwise now. But understand this, when you ask that she shall come back to you, I do not refuse it on my own account. Though I should be miserable indeed were she to leave me, I will not even ask her to stay. But I know she will stay. Though I should try to drive her out, she would not go. Goodbye, sir.” The old man only shook his head. “Goodbye, Robert.”

Anthony Trollope

From John Caldigate. Born in London, Trollope moved to Ireland at the age of twenty-six in 1841 after volunteering to serve there as a postal inspector. This novel, one of forty-seven he wrote, was serialized in Blackwood’s Edinburgh Magazine in 1878–79. The eponymous hero is ultimately cleared of bigamy charges after postmarks on a letter are proved to have been forged. “It is the only one of Trollope’s books,” wrote the British publisher and literary historian Michael Sadleir, “in which for the purpose of his plot he uses his knowledge and experience of the post office.”