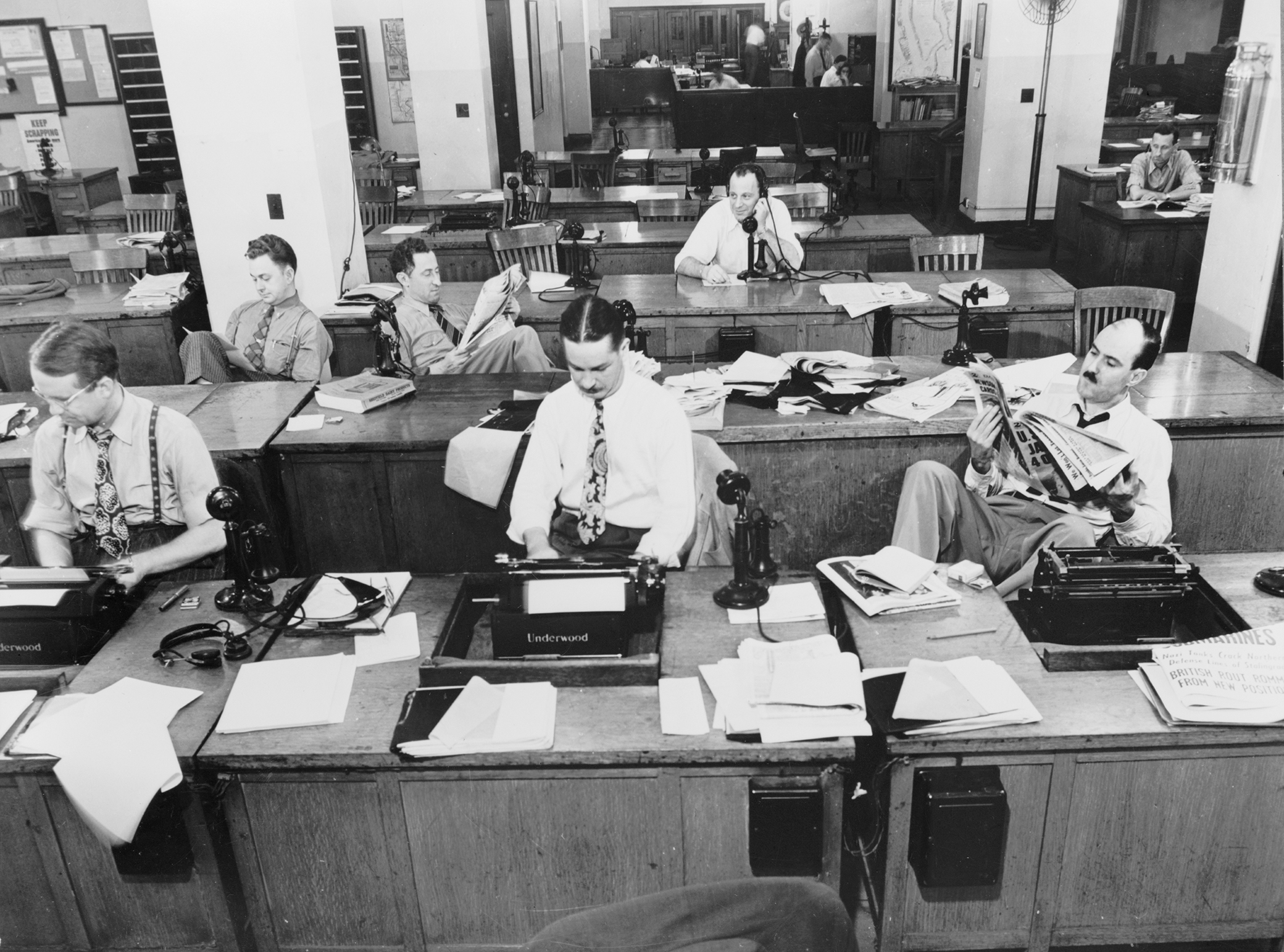

The New York Times newsroom, 1942. Photograph by Marjory Collins. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

In 1943 University of Chicago president Robert Maynard Hutchins formed the Commission on Freedom of the Press, which sought to study and diagnose the current state and possible futures of American journalism, with funding from Henry R. Luce of Time Inc. The members (all white males) of the group included theologian Reinhold Niebuhr, poet and playwright Archibald MacLeish, philosopher William Ernest Hocking, Hunter College president George N. Shuster, political scientists Charles E. Merriam and Harold D. Lasswell, and law professors Zechariah Chafee Jr. and John Dickinson. Conducting a thirteen-man inquiry into freedom of the press proved more difficult than Hutchins had anticipated.

In 1950, three years after the commission’s report, A Free and Responsible Press, was published, researcher Llewellyn White typed up a sour reflection on his experience. The commission had crafted its understanding of journalism from “shadows, legends, and professors’ books,” he told Max Ascoli, his boss at the Reporter magazine. A better approach would have been to convene small groups of conscientious journalists and, he said, have “them tell us what ails them,” thus developing “a sympathetic bill of particulars virtually drafted by the best elements in the press themselves.” He closed on a note of futility: “Looking back on it, though, I doubt if any such result would have been possible, given the personalities involved…Perhaps our one useful legacy was a demonstration of how not to conduct a citizen inquiry into the press.”

Whether led by Robert Hutchins or someone else, commission conversations often meandered. “Our discussion on this subject, like most of our discussions, is a trifle circular,” Hutchins said in one meeting. To a friend, he wrote, “The only conclusion the Commission has reached to date is that it cannot figure out what to do about the freedom of the press.”

At times commission members couldn’t even agree on their overarching mission. After eight meetings and more than a year, George Shuster said, “our purpose has never been defined with adequate care.” Archibald MacLeish thought they should emphasize First Amendment law. Charles Merriam said their analysis ought to be “cultural-philosophical-ethical-cooperative-democratic.” Harold Lasswell and William Ernest Hocking wanted to concentrate on policy. Hutchins at the outset said they were working to solve policy problems; at the end, he said their task was philosophical. Henry Luce provided no help. At various times, he said he expected an abstract analysis of philosophy and morality, practical guidance for editors, “a disquisition on worldwide freedom of the press,” a statement that would inspire the public to support press freedom, and an investigation of the media’s cultural impact.

Beyond the scope of the study, some of the views of commission members were incompatible. The point is not that members disagreed, though they did, but that some of their consensus positions could not be reconciled with other consensus positions. “We are against absentee ownership, we are for the expression of conviction,” Hutchins said. “Yet I suppose we feel that the worst newspaper situations in this country are those where the owners are most active and most deeply convinced.” He cited William Randolph Hearst, Robert R. McCormick, and Joseph Medill Patterson. “It would be fine if either they would not express their convictions, or if they were absentees.”

Many other inconsistencies arose. They wanted the press to publish only truthful material while offering an open forum for diverse voices, but some of the diverse voices might propagate falsehoods. They wanted the press to reduce social divisions by providing balanced representations of minorities, but they also wanted editors to resist the demands of self-interested groups trying to influence coverage, including, in Merriam’s words, “extremely touchy minorities.” They wanted fact separated from opinion, but they also wanted “the truth about the fact,” which, Niebuhr maintained, is a matter of opinion. They lamented the ineffectiveness of journalistic ethics codes, but they also lamented the effectiveness of the Hays Code over movies. They wanted owners to keep their hands off newspaper content, but when told that an owner had instructed a columnist to attack Eleanor Roosevelt no more than three times a week, Dickinson called it “a modest request.” They applauded editors who stood their ground in the face of a boycott by Father Charles Coughlin’s followers, but they also supported editors who, when Jewish advertisers threatened a boycott, agreed to devote more coverage to Nazi atrocities. Broadly, they wanted the press to be both “free from the menace of external compulsions from whatever source” and “accountable to society”—“two different perspectives,” said Niebuhr, “which have never really been worked out.”

The commission staff had its own problems. Eric Hodgins of Time Inc. called Robert Leigh, who directed the Commission on Freedom of the Press staff, “an estimable gentleman on whose imagination and humor I would hate to rely if I were the only other inhabitant of a desert island.” Elsewhere he said of Leigh, “no Aristotle, he.” Like Hutchins, Leigh had lost interest in his job in higher-education administration, as founding president of Bennington College. Faculty and staff complained about his inattention, and at the request of the chair of the board of trustees, he resigned in 1941. The following year, he became director of the Foreign Broadcast Intelligence Service at the Federal Communications Commission. He left the FCC in 1944, when Hutchins hired him.

Although Leigh’s specialty in political science was administrative organization, at the commission he proved unable to handle a three-person staff. “I hope and pray we are going to get through this job without undiplomatic developments,” MacLeish told Hutchins in early 1946, after spending time in the commission offices. The researchers “disagree among themselves on some of the basic facts,” he said, and “my attempts to get them to reconcile their differences have turned up an underlying unhappiness.”

Llewellyn White was the most disruptive figure. A longtime journalist, he joined the commission as a researcher in December 1944 and rose to assistant director in October 1945. Though prolific, he antagonized colleagues, lashed out in response to criticism, and at times adopted a tone that Merriam characterized as “supercilious” and “execrable.” White later told the FBI that another commission researcher, Milton Stewart, was immature, unstable, neurotic, egotistical, a self-described former Trotskyite, and a security risk. The third researcher, Ruth Inglis, considered White “a louse.”

Development of the final report brought all the commission’s troubles to the fore.

At the end of 1944, Archibald MacLeish resigned from the group. The Franklin D. Roosevelt administration had nominated him to be assistant secretary of state for public and cultural relations, and he thought that the new position “simply won’t mix with the commission’s work.” At the State Department, MacLeish worked to build public support for the United Nations. He resigned after eight months, following the death of FDR, and returned to the commission.

“Now I have some hope for our commission,” Hutchins said. He had a job for MacLeish. The legacy of the inquiry would rest on their final report. Because the recommendations were unexceptional, the report’s renown would depend on its “tone, style, and literary quality.” So he asked the Pulitzer-winning poet to draft it. MacLeish agreed.

Leigh had been working on the report since joining the staff a year earlier. In fact he started even before the group had formulated research questions. “This may seem like putting the cart before the horse,” he said, “but it avoids having the mountain bring forth a mouse.” His prose tended toward the leaden: “If in all the five media, there could be such a provision of highly qualitative units available to all, it would be a most promising means of raising standards by increasing diversity with the means of developing audience discrimination, training junior professionals, and altering the sense of prestige and success in the mass media generally so as to include recognition of high quality as well as profitable quantity.” Some of his points were trifling, too. In one draft, he called on the media to reject ads for palm readers. He included a chart showing that children liked the comic strip Dick Tracy, whereas the elderly preferred Bringing Up Father.

MacLeish began writing the report in October 1945, at a salary of $900 a month, and completed a draft in January 1946. He opened with a slam at his former Fortune boss, Henry Luce: in sponsoring the study, Time Inc. cared only about “freedom of the press from interference by government,” but the press was already freer in this regard than ever before. MacLeish went on to vilify conservative publishers and praise the Roosevelt administration. He also contrasted the American press and the Soviet press. American journalists construe freedom of the press as a duty to be irresponsible, he wrote, whereas Soviet journalists view it as a duty to be “responsible to the people—or at least to a government which claims to be the people.”

“I am delighted with the style and dash of the draft report,” Hutchins told MacLeish. “If I have a general criticism, it is that the draft is too dashing and gives a partisan impression.”

When the commission assembled at the end of January at the Carlyle Hotel in New York, others took issue with MacLeish’s draft. They deemed it too negative, too quick to impute bad motives, too incendiary, and as Hutchins had said, too partisan. Niebuhr suggested a shift in register from “moral indignation to moral imperative.” Some of the men thought MacLeish was setting too high a standard for the press. They shouldn’t “demand the impossible,” Hutchins said. “The problem is awfully complex,” said Dickinson.

MacLeish replied that they mustn’t get lost in complexity. “Unless your analysis is simple enough to make a recommendation,” he said, “we are going to be one of the funniest groups of people who have met for three years. We have to come out with some answer.”

Niebuhr wasn’t sure. “Maybe this is wrong,” he said, “but I think that actually we have an insoluble problem. If you have an insoluble problem for which you can only find proximate solutions, you are not going to give very tremendous solutions which will shock the whole world. But if you have an insoluble problem of great complexities, and you illumine the complexities, you may be able to make quite a great contribution.”

“Are we willing to come out with a statement that this is an insoluble problem?” MacLeish asked. “Because if we are, this report is going to be helped a great deal.”

“All great problems are insoluble,” Niebuhr replied.

“The word insoluble is a little strong,” said Hutchins.

MacLeish called for a vote on whether the problem was insoluble.

Hutchins tried to placate everyone. He said he would be happy with “a thorough, penetrating, vigorous analysis of an extremely difficult problem” that “pointed the way to future possible solutions,” even if it didn’t have all the answers.

On February 15 MacLeish sent Hutchins his second draft. Zechariah Chafee said he was willing to sign the revision. The report’s recommendations against government action largely reflected his views, and he seemed willing to compromise on all else. But others continued to find fault. Leigh, perhaps miffed that authorship had been taken from him, was especially caustic. He said the draft oversimplified the problems, overstated the role of the citizen, distorted the meaning of the First Amendment, and omitted important issues. He considered it worse than MacLeish’s original. The mild-mannered Leigh’s response surprised MacLeish, who told Hutchins, “The miracle of the loaves into the fishes was nothing at all compared to the miracle of milk toast into red meat which a typewriter works in Leigh’s spirit.”

MacLeish had to miss the next meeting, from March 31 to April 2 at the Shoreland Hotel in Chicago. In his absence, the commission decided to junk his draft and work from a series of lectures that Leigh had given in Seattle, which included toned-down passages from MacLeish. Hutchins wired MacLeish that the commission planned “to retain large sections” of his draft alongside additional material by Leigh.

In the 1930s, when MacLeish was Fortune’s star writer, an editor said that “Arch is very easy to handle editorially provided you don’t change as much as a comma in his copy without consulting him.” When MacLeish saw Leigh’s rewrite, he was irate.

Adapted from An Aristocracy of Critics: Luce, Hutchins, Niebuhr, and the Committee That Redefined Freedom of the Press. Copyright © 2020 by Stephen Bates. Used with permission of the publisher, Yale University Press. All rights reserved.