Revolutions are not about trifles, but they are produced by trifles.

—Aristotle, 350 BCLanguage Police

Trotsky takes on swearing.

I read lately in one of our papers that at a general meeting of the workmen at the “Paris Commune” boot factory, a resolution was carried to abstain from swearing, to impose fines for bad language, etc.

This is a small incident in the turmoil of the present day—but a very telling small incident. Its importance, however, depends on the response the initiative of the boot factory is going to meet with in the working class.

Abusive language and swearing are a legacy of slavery, humiliation, and disrespect for human dignity—one’s own and that of other people. This is particularly the case with swearing in Russia. I should like to hear from our philologists, our linguists, and experts in folklore whether they know of such loose, sticky, and low terms of abuse in any other language but Russian. As far as I know, there is nothing, or nearly nothing, of the kind outside Russia. Russian swearing in “the lower depths” was the result of despair, embitterment, and, above all, of slavery—without hope, without escape. The swearing of the upper classes, on the other hand, the swearing that came out of the throats of the gentry, the authorities, was the outcome of class rule, slave owner’s pride, unshakable power. Proverbs are supposed to contain the wisdom of the masses—Russian proverbs show besides the ignorant and the superstitious mind of the masses and their slavishness. “Abuse does not stick to the collar,” says an old Russian proverb, not only accepting slavery as a fact, but submitting to the humiliation of it. Two streams of Russian abuse—that of the masters, the officials, the police, replete and fatty, and the other, the hungry, desperate, tormented swearing of the masses—have colored the whole of Russian life with despicable patterns of abusive terms. Such was the legacy the Revolution received among others from the past.

But the Revolution is, in the first place, an awakening of human personality in the masses—who were supposed to possess no personality. In spite of occasional cruelty and the sanguinary relentlessness of its methods, the Revolution is before and above all the awakening of humanity, its onward march, and is marked with a growing respect for the personal dignity of every individual, with an ever-increasing concern for those who are weak. A revolution does not deserve its name if, with all its might and all the means at its disposal, it does not help the woman—twofold and threefold enslaved as she has been in the past—to get out on the road of individual and social progress. A revolution does not deserve its name, if it does not take the greatest care possible of the children—the future race for whose benefit the revolution has been made. And how could one create day by day, if only by little bits, a new life based on mutual consideration, on self-respect, on the real equality of women, looked upon as fellow workers, on the efficient care of the children—in an atmosphere poisoned with the roaring, rolling, ringing, and resounding swearing of masters and slaves, that swearing that spares no one and stops at nothing? The struggle against “bad language” is a condition of intellectual culture, just as the fight against filth and vermin is a condition of physical culture.

To do away radically with abusive speech is not an easy thing, considering that unrestrained speech has psychological roots and is an outcome of uncultured surroundings. We certainly welcome the initiative of the boot factory, and above all we wish the promoters of the new movements much perseverance. Psychological habits that come down from generation to generation and saturate the whole atmosphere of life are very tenacious, and on the other hand, it often happens with us in Russia that we just make a violent rush forward, strain our forces, and then let things drift in the old way.

Let us hope that the working women—those of the communist ranks in the first place—will support the initiative of the “Paris Commune” factory. As a rule—which has exceptions, of course—men who use bad language scorn women, and have no regard for children. This does not apply only to the uncultured masses, but also to the advanced and even the so-called responsible elements of the present social order. There is no denying that the old prerevolutionary forms of bad language are still in use at the present time, six years after October, and are quite the fashion at the “top.” When away from town, particularly from Moscow, our dignitaries consider it in a way their duty to use strong language. They evidently think it a means of getting into closer contact with the peasantry.

PS. The fight against bad language is also a part of a struggle for the purity, clearness, and beauty of Russian speech.

Reactionary blockheads maintain that the Revolution, without having altogether ruined it, is in the way of spoiling the Russian language. There is actually an enormous quantity of words in use now that have originated by chance, many of them perfectly needless, provincial expressions, some contrary to the spirit of our language. And yet the reactionary blockheads are quite mistaken about the future of the Russian language—as about all the rest. Out of the revolutionary turmoil our language will come strengthened, rejuvenated, with an increased flexibility and delicacy. Our prerevolutionary, obviously ossified bureaucratic and liberal press language is already considerably enriched by new descriptive forms, by new, much more precise and dynamic expressions. But during all these stormy years our language has certainly become greatly obstructed, and part of our progress in culture will, among other things, show in our casting out of our speech all useless words and expressions, and those that are not in keeping with the spirit of the language, while preserving the unquestionable and invaluable linguistic acquisitions of the revolutionary epoch.

Vercingetorix Before Caesar, by Henri-Paul Motte, 1886. Vercingetorix led the last uprising of the Gallic peoples against Julius Caesar in 52 bc before the complete subjugation of Gaul. Musée Crozatier, Le Puy-en-Velay, France. Giraudon, The Bridgeman Art Library.

Language is the instrument of thought. Precision and correctness of speech is an indispensable condition of correct and precise thinking. The political power has passed now, for the first time in our history, into the hands of labor. The working class possesses a rich store of work and life experience, and a language based on that experience. But our proletariat has not had sufficient schooling in elementary reading and writing, not to speak of literary education. And this is the reason why the now governing working class, which is in itself and by its social nature a powerful safeguard of the integrity and greatness of the Russian language in the future, does not, nevertheless, stand up now with the necessary energy against the intrusion of needless, corrupt, and sometimes hideous new words and expressions. To preserve the greatness of the language, all faulty words and expressions must be weeded out of daily speech. Speech is also in need of hygiene. And the working class needs a healthy language not less but rather more than the other classes; for the first time in history it begins to think independently, about nature, about life and its foundations—and to do the thinking it needs the instrument of a clear incisive language

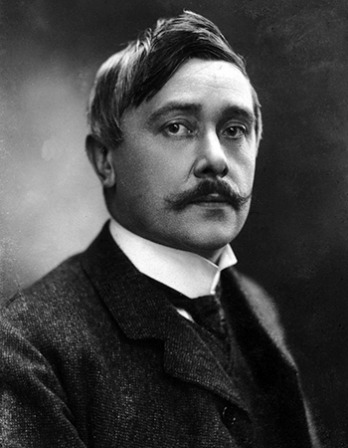

Leon Trotsky

From “The Struggle for Cultured Speech.” As the commissar of war and one of the five members of the Politburo, Trotsky published this article in Pravda. After Vladimir Lenin died in 1924, Joseph Stalin consolidated his power within the Central Committee and organized denunciations of Trotsky as a reactionary and betrayer of Leninism. Trotsky was banished from the Soviet Union in 1929 and murdered in Mexico in 1940.