The almost insoluble task is to let neither the power of others, nor our own powerlessness, stupefy us.

—Theodor Adorno, 1951Istanbul Panorama

Turkey’s largest city has a long history of cosmopolitanism, but how does its cosmopolitan past differ from its cosmopolitan present?

By Bernd Brunner

Le Bosphore by James Robertson and Felice Beato, 1857. Albumen print, one of a five-part panorama of Constantinople, taken from the Beyzait Tower. Ömer M. Koç Collection.

In 1850, when Gustave Flaubert visited Istanbul, or Constantinople, as it was still called, he wrote of discovering a fantastic “human anthill,” which he expected to become “the capital of the world”: “You know that feeling of being crushed and overwhelmed that one has on a first visit to Paris: here you are penetrated by that feeling, elbowing so many unknown men, from Persian and Indian, to the American and Englishman, so many separate individualities which, in their frightening total, humble your own.” Herman Melville, who spent six days in Constantinople in December 1856, found the city labyrinthine and often got lost. “Came home through the vast suburbs of Galata,” he noted in his journal. “Great crowds of all nations…coins of all nations circulate—Placards in four or five languages (Turkish, French, Greek, Armenian)…You feel you are among the nations…Great curse that of Babel; not being able to talk to a fellow being.”

Mark Twain came to Constantinople a decade later to see what he characterized as “an eternal circus”: “People were thicker than bees in those narrow streets, and the men were dressed in all the outrageous, outlandish, idolatrous, extravagant, thunder-and-lightning costumes that ever a tailor with the delirium tremens and seven devils could conceive of.” Constantinople, at the intersection of Europe, Asia, and the Middle East, with its unusual human mosaic, was a place that welcomed nearly everyone.

Prominent visitors like Twain and Melville were far from the first moderns to describe the variousness of the city and the exceeding hospitality of its residents—which is said to derive from the Turks who traveled from the Central Asian steppe and depended on the help of foreigners along the way. Genoese and Venetian merchants came to the city in the eleventh century and marveled at the city’s hospitality. While the Jews’ presence in Anatolia reaches far back in time, Constantinople also became a refuge for Sephardic Jews fleeing the Spanish Inquisition in the late fifteenth century; Sultan Bayezid II formally invited them to settle in the empire, and they enjoyed relative tolerance, with no restrictions on the professions they could practice and hardly any major friction with the Turks.

Iran, Untitled, by Gohar Dashti, 2013. Archival inkjet print. © Gohar Dashti, courtesy the artist and Robert Klein Gallery, Boston.

Lady Mary Montagu, wife of a British ambassador, who visited the city more than one hundred years before Twain, surprised her readers by applauding the Turks in their humanity even toward slaves, whose treatment she found “no worse than servitude all over the world.” In 1800, an American frigate, the George Washington, reached the city from Algiers, one of the first American ships to arrive in an Ottoman port. Captain William Bainbridge ordered the American flag to be raised and, in response, the government sent a messenger to ask “whether America was not otherwise called the New World and, being answered in the affirmative, assured the captain that he was welcome and would be treated with the utmost cordiality and respect,” as one eyewitness wrote. In short order, trade flourished between American and Ottoman merchants, with cotton, oil, and rum being in particular demand. It was an ironic business: the Americans who were promoting temperance at home exported millions of gallons of alcohol to a Muslim country. (The rum was shipped on to Georgia, Armenia, and Persia.)

Constantinople also attracted European and American tourists looking to range beyond the Grand Tour, which included Italy and Greece but typically stopped short of Anatolia and the Golden Horn. These adventurers often combined their visit with a trip to the Holy Land. On the Bosphorus they found a deep tradition of cosmopolitan culture that combined Muslim, Jewish, and Christian influences. In the 1830s, the presence of American missionaries (who proselytized to Greek and Armenian Christians, believing their faith to be corrupted by false doctrines) added a final touch to this curious mix of diplomatic, commercial, and religious intermingling.

During the years Flaubert, Melville, and Twain wrote about Constantinople’s rich diversity, the city was actually in the process of transforming itself into an even more cosmopolitan city, a kind of “London of the East,” a place that not only tolerated outsiders but actively recruited and welcomed foreigners from all over the world. The Ottoman sultans during this period were trying to emulate the cultural, economic, and military strides Europe had made. Their ultimate goal was to enter the post-Napoleonic club of European states.

Earlier efforts in this direction had been limited to the military. In the late eighteenth century, under Sultan Selim III, the armed forces had adopted Western armaments and training methods, and the janissaries—the elite Ottoman corps made up for the most part of Christian converts—were abolished. By 1838, the Ottoman administration had established ministries of the interior, of foreign affairs, and of justice. But the new era officially began with the Noble Edict of the Rose Chamber in 1839. Its aims included equality for members of all religions as well as secularized laws and state institutions—an admission, perhaps, that a crumbling empire, which had been shedding territories, needed new ideas to match Europe’s rapid economic rise. The resulting political movement, the Tanzimat, a reordering of the Ottoman Empire, lasted for close to four decades.

During this period, many Turks traveled to cities like Paris to study or gain work experience. Among them was the statesman Mustafa Reshid Pasha, who served as his country’s foreign minister and as the Ottoman ambassador in Paris. The “father of the Tanzimat,” Reshid Pasha was responsible for introducing French-inspired laws and the abolition of slavery. The prohibition against the conscription of Christians was lifted and a new army created. Even the sultans adapted to the new foreign style. They gave up their traditional garb of a kavuk (a high cap with a turban wrapped around it), caftan, and salvar (wide Turkish trousers), appearing instead in straight striped slacks, a red fez, and a jacket with padded shoulders. There were further reforms in the fields of commerce, law, and education, and foreign merchants were allowed to trade freely within the empire.

While the Tanzimat period lasted only until 1876 and could not prevent the empire’s inevitable financial collapse, it nevertheless paved the way for future modernization efforts. Mustafa Kemal, founder of the Turkish nation (who later received the surname Atatürk, “the father of the Turks”), didn’t rise out of nowhere; he was a direct product of this era. Born in Salonika (Thessaloniki) in 1881, he had come into early contact with innovations such as rail travel, electricity, and telephones, and he attended a military preparatory school where he enjoyed a mix of classical Ottoman and modern French education.

The Ottomans didn’t simply imitate Western skills: they invited outsiders to teach them. As such, the Tanzimat saw another great flourishing of foreigners in Constantinople. The Italian Donizetti Pasha was recruited for the task of transforming the military orchestra into a modern ensemble. John Belton Davis came from South Carolina to create a cotton plantation west of the city in San Stefano (now Yeşilköy). He even brought his slaves—but made sure to take them back again before seven years had passed, so they would not gain their freedom under Ottoman law. Henry Eckford, of New York, was commissioned to superintend the construction of the navy. The American chemist John L. Smith was hired to search for mineral deposits, and he found coal and ore. The French engineer Eugène Henri Gavand had the job of designing a 0.345-mile-long subterranean funicular; when it was finally launched in 1875, Constantinople’s residents could easily ascend the steep Galata Hill—sometimes known as “the hill of the infidels” for its proximity to the European district. The missionary Cyrus Hamlin founded Robert College, which later morphed into Bosphorus University, one of Turkey’s most prestigious state universities. Looking back on thirty-five years spent in the country, Hamlin wrote in 1896 that the Ottoman Empire “was an exceptionally safe and inviting field of labor. More than four hundred missionaries, men and women, have given their lives to that work…and many are buried in Turkish soil.”

One of the more interesting of the Tanzimat imports was an Englishman named James Robertson, who was recruited to modernize the Ottoman mint in 1840. That Robertson accepted the posting was itself unusual: many of his most talented technical colleagues were assuming prestigious posts throughout the British Empire. But Robertson sensed an epochal opportunity in Constantinople.

Robertson was trained in London as an engraver, where he accumulated years of experience and made four medals at the Royal Academy between 1833 and 1840. When he was twenty-eight years old, Robertson was invited to Constantinople and offered control of the mint and a generous salary of forty English pounds. He accepted. The first gold coins minted under his direction were issued on January 17, 1843. Abdülmecid I, crowned the empire’s thirty-first sultan four years earlier, had wanted to bring the mint up to date, but he eventually went well beyond this goal and actually built a replica of the London mint on the grounds of his palace, the Topkapi Sarayi.

The coinage Abdülmecid I turned out was the most sophisticated ever produced in the Ottoman Empire, and his calligraphic monogram—known as a tuğhra, a symbol of the sultan’s sovereignty—became known all over the world. Robertson was more modest—only one medal bore his signature: a coin commemorating the restoration of the Hagia Sophia, a project also carried out by a foreigner: Gaspard Fossati, a Swiss architect.

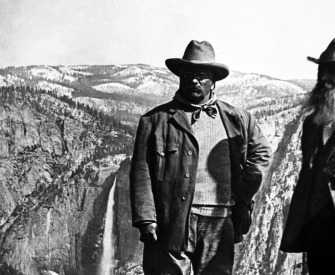

But Robertson’s work in Constantinople didn’t end with his work at the mint. In May 1854, he climbed the Bayezid Tower, a 279-foot structure belonging to the Ottoman Ministry of War. The tower itself, built thirty years previously by the Armenian master builder Senekerim Amira Balyan, was made of stone and contained a wooden spiral staircase with 180 steps. Robertson made a brief circuit of the top before setting to work. From the windows of the uppermost floor he took twelve photographs, which he later combined to create a panorama.

Panorama—a word coined from the Greek roots pan (all) and horama (view)—had long been an acknowledged technique of landscape painting, developed by several different painters in parallel, to produce a 360-degree view of a place. Perhaps Robertson’s photographic experiment was prompted by an urge to see and record the city’s modern expanse spread out around him, or perhaps he was hired to create the image. Either way, it was the first photographic panorama of Constantinople.

Reception of a Venetian Delegation in Damascus in 1511 (detail). Venetian school, c. 1525. Louvre, Paris, France.

Robertson’s images made waves abroad, and directed much attention to the city. In August, the Illustrated London News announced that it had received the photo series and praised the photographer. The panorama was exhibited at the Paris Exposition the following year and in a show by the Photographic Society of Scotland the year after that. In light of the pioneering effort the panorama represented, critics generously forgave small errors in its execution. Robertson more successfully mastered these challenges on a second try in 1857. Though Robertson’s photographic work constitutes only a small piece of the Tanzimat puzzle, his widely distributed photos, combined with a wave of travel reports and articles (and the possibility of rapid travel by steamship) in turn attracted more visitors to the city.

By the time Robertson created his panorama, he had already spent more than fifteen years in Constantinople. He lived on Asmalı Mescit Street, up on the hill in Pera, where life for European expatriates was concentrated. Churches were plentiful there, and hardly anyone wore a fez or a turban. Like their counterparts in Western capitals, women donned corsets, carried parasols, and did up their hair. French author Gérard de Nerval, who spent three months in Constantinople in 1843, wrote that during his stay he felt as though he were in a “European city where the Turk himself has become a foreigner.” He certainly based this assessment primarily on his own neighborhood of Pera, which he dubbed a “veritable Parisian district.” The neighborhood featured many of the comforts of Western capitals, including hotels and coffeehouses where people ate with forks and knives. There were Armenians, Greeks, French, Germans, English, and Americans. And not only did Pera’s residents speak many languages, they could visit shops with foreign books and buy many newspapers printed in Europe.

In 1855, Robertson married Leonilda Beato. She belonged to a Levantine family with roots in Venice. Robertson later taught the craft of photography to his wife’s brother, Felice Beato. He also freed himself from responsibilities at the mint to work as a photographer during the Crimean War, in which England, France, and Sardinia allied themselves with the Ottoman Empire to fight against Russia. The scenes that Robertson shot with Felice Beato are among the earliest examples of war photography. An 1855 salt print tinted with watercolors shows Robertson with his brother-in-law. He wears Turkish garb: a yellow shirt with a red-and-white-striped sash, a red cap, wide white trousers, and red sandals.

It was no accident that the empire’s first photographers were foreigners. Islam does not actually condemn photographs, but it does forbid venerating or worshiping them. The first Muslim-operated photo studio in Istanbul would not open until 1910.

In 1867, Robertson and Beato gave up their photography business. They offered their equipment, negatives, and stereoscopic prints up for sale in the Levant Herald, along with a two-horse coach they had brought from Transylvania. Felice Beato then left for the Far East.

Today, Istanbul—with a population of more than fourteen million—is on its way to becoming a cosmopolitan city again, though not akin to London or Paris. In most neighborhoods, you will rarely if ever run into people recognizable as foreigners. Turkey is now an overwhelmingly Muslim country—more than 99 percent, by a recent estimate.

There are, however, plenty of newly arrived foreigners, though they may be difficult to spot. Many come from other Middle Eastern countries or the former Soviet Union (and then often speak a mother tongue related to Turkish). And among the city’s Muslim population there is in fact much diversity, with significant populations of Sunnis, Kurds (who are mostly Sunnis), and Alevis (who can also be Kurdish).

The number of Christians and Jews permanently residing in the city is now very small, much smaller than it was 150 years ago. The twentieth century transformed the city, eradicating much of its historic diversity. The aftermath of the Istanbul pogrom of 1955 drove most of the Greeks away, and most of the city’s Jewish population emigrated to Israel. Yet you can still hear both church bells and the azan, the call to prayer, in Istanbul. There are few cities in the Muslim world where this is the case, but both continue to sound out today in my neighborhood—the same one where James Robertson once lived. Until well into November, when you finally have to close the windows, you can hear the voice of the muezzin rising from the nearby mosque as the sunset nears. Others soon join in. These voices—some louder, some softer—seem to swell from the belly of the city, coming from different directions and singing past one another.

France has neither winter, summer, nor morals—apart from these drawbacks it is a fine country.

—Mark Twain, 1879The Bayezid Tower, where Robertson shot his panoramic photos, still stands just seven tram stops away from my home. It is tucked away in a park that is only accessible from the Sülemaniye Mosque, a few minutes’ walk from the turbulent Grand Bazaar. After passing a security checkpoint, I find myself before a stone tower built in the Ottoman style. It was damaged in the earthquake of 1889, but later restored. The white structure soars into the air, but I am not allowed to enter. Back on the other side of the city, I go looking for the building that housed James Robertson’s photo studio: 293 Grande Rue de Péra, at the corner of Rue de la Poste. Despite all the changes during the last 150 years, the layout of the streets in what was once Pera has not changed, though today the streets are called İstiklâl Caddesi and Postacılar Sokağı. A well-heeled art foundation occupies the spot where the photo studio once stood. Outside, a seemingly endless stream of pedestrians flows past. A group of four or five men call out, “Ruski?” a few yards behind me. At first I don’t realize that they are talking to me, but I eventually turn around and shake my head.

Istanbul’s reemergent cosmopolitanism has been hastened by people fleeing war and chaos, immigrants who hope to find safe haven in the city or by traveling through it. Refugees now stream into Istanbul from Iraq and Syria: more than one million Syrians have poured into Turkey in the three years since the beginning of the Syrian civil war—one of the great tragedies of our new century. These new immigrants test the Turks, who remain famed for their warmth and generosity. Many residents feel the Syrians don’t belong, their language and lifestyle being too different, and fear that they are competing with them for jobs.

But while European countries debate how many refugees they can accept and how best to manage the process, it is now virtually impossible for migrants from the Middle East to reach Europe safely and legally, especially since Greece has fortified its border. The fate of Kurds in Iraq, Syria, and Turkey—and the possibility of an independent Kurdish state—is said to be a great concern in Turkey. But it is rarely mentioned that the city with the largest Kurdish population isn’t deep within traditional Kurdish territory, like Diyarbakir in Turkey’s east, or Arbil in Iraq. In fact, more Kurds—three million of them—live in Istanbul than in any other city in the world. Most of them still speak Kurdish, a language unrelated to Turkish but, like Farsi—and English for that matter—one of the Indo-European tongues. Istanbul’s Kurds and those of the other large cities in western Turkey are very often assimilated into Turkish society. They want respect, but they are far from united on the question of an independent state.

Other foreigners come to the city under more privileged circumstances. They stay in luxury hotels and try to be someone else for a few days. Or they somehow get stranded here by choice, as I did. There’s a pattern to the way the city drew me in that I am only beginning to recognize. It felt like climbing without knowing where I was going or when I would get there. Each time I came here I stayed a little longer, drawn by the energy and intensity of the place, attracted by different sounds, smells, and tastes, the prospect of a different, less predictable life. At a certain point, I realized that Istanbul had become my home.

Born and raised in isolated West Berlin, I became tired of my country’s obsession with its reunification and the perfection of the material aspects of life. I had achieved a life of relative security in the city, but I had also long had the feeling that I should leave: a “new Berlin” was emerging, and I wasn’t sure I had a place in it. I didn’t understand a word of Turkish when I first arrived, but, perhaps because I had always had Turkish classmates in Berlin, I immediately felt a little at home in this huge city by the sea. I have never regretted my decision.

Yabancı mısınız? “Are you a foreigner?” It’s a question I sometimes get. But the term used in Turkey for “foreigner” can also simply mean someone who’s not from Istanbul; in other words, a stranger to the city. In the Turkish tradition, special protection is still extended to strangers. It’s a nice thought, and indeed I never feel threatened here. In fact, I feel safer than I did in Berlin; attacks or murders of foreigners do happen, as anywhere, but they are absolute exceptions.

The people in my neighborhood do not expect that a foreigner would take the trouble to learn their language. They cannot speak more slowly or clearly, even when I ask them to. But how could I hold that against them? My knowledge of other foreigners in Istanbul comes to some degree from my lessons at a language school. Most of the students are Syrian or Russian, but Japanese, Germans, Italians, Americans, and Iranians are represented as well. The Arabs don’t have an edge when it comes to learning the language, as Arabic doesn’t bear any grammatical relation to Turkish (although you can find many Turkish words with an Arabic or Persian root). The Japanese students are somewhat more difficult to understand, but it’s obvious that they intuitively understand the structure of Turkish. Mika, a fellow student who is in Istanbul for an unspecified time to work for an international business consultancy, explains that Japanese, like Turkish, is agglutinative: it functions by attaching elements of meaning to words.

At the language school, I also meet Marcelo, an older Franciscan priest from Argentina. Curious, I ask to see the monastery where he lives, which belongs to the Church of St. Anthony of Padua. The neo-Gothic basilica was once one of three Levantine parish churches in the area. Marcelo showed me and a Turkish friend around. Everything was meticulously clean and smelled slightly stuffy; the atmosphere reminded me of an old elementary school. Marcelo let us peek into the chapel and the library, where books in other languages were piled up to the ceiling, a sight that conjured a forgotten time.

Glass Ceilings (For Ghazal Shakeri), from the series Listen, by Newsha Tavakolian, 2010. The series features Iranian female singers prohibited by the state from performing solo or producing their own albums. © Newsha Tavakolian, courtesy the artist and Robert Klein Gallery, Boston.

During my first year in the city, I lived in a poor and slowly gentrifying area called Tarlabaşı (Turkish for “top of the field”), formerly populated mostly by Greeks and Armenians. Today, it’s the home of Kurds and some Gypsies. Some Africans also have their homes there. Apart from a glance and the occasional greeting, I didn’t have much contact with my neighbors. Our lives just didn’t have enough in common to form the basis for a continual exchange.

When I went to the central police station to get my residence permit, I realized that Europeans and Americans constitute a rather small share of the foreigners now applying for legal status. The station was a huge structure, filled with people and in dire need of effective ventilation. As I waited in line, I heard the applicants being called by their first names and their countries of origin. Most of the people around me came from places to the east or south of Turkey: Syria, Turkmenistan, Iran, Kazakhstan, Afghanistan. There were just a handful of Europeans—students on the Erasmus student exchange program.

Pera, now part of the more comprehensive Beyoğlu, is still not representative of Turkey, or even Istanbul. It functions as the gateway to the city. The center of a vibrant art scene, most of the foreign cultural institutes and consulates are here, as well as many boutique hotels. Property values are shooting up, and there is a fight for the preservation of historic structures. It’s also a destination for people who want to listen to music and party in one of the many glitzy or run-down nightclubs and a place for people who want to drink and dabble in drugs. Three million people are said to flock to Beyoğlu every weekend. The nights can overwhelm the senses. I’ve made a few attempts to enter one of the clubs before, but always backed out at the last minute.

One night I decide I should venture into this world. At the entrance to a club, located just a few steps from Taksim Square, Arab tourists stroll past, the women veiled in black except for an opening around their eyes. They seem completely unaware of the parallel universe inside. The dance floor opens just beyond the entrance. A metallic beat competes with the sound of cars rolling past the open door only a few feet away. Just after I enter, a young man with bleached-blond hair pulls up his brightly colored T-shirt to expose his stomach. A cloud of eau de toilette wafts over me, with an intense, one-dimensional fragrance. Further back, androgynous guests compete for the attention of other visitors who are clearly men. A few dance and admire themselves in a large mirror. They tousle their hair, pucker their lips, and pose as if the entire world were watching. Laughter and banter surround me. I meet a woman named Sare. She greets me with an enthusiastic “Welcome to Turkey!” She is a male-to-female transsexual who has fled Iran. In this new version of Istanbul, it’s possible for Sare to live as she chooses, even if society has hardly any respect for her.

I try to see the city of today through the eyes of James Robertson. If he were to photograph Istanbul today, what spot would he choose as his vantage point? The rooftop terrace of 360, a fashionable Beyoğlu restaurant? Or one of the many high-rise buildings? Would he seek out a location in Levent, the financial district, or ascend the twin tower of Ataşehir on the Asian side? The number of places offering a bird’s-eye view has multiplied dramatically in just the last ten years—during which seventy such buildings have been erected—and there’s no end in sight. Fifteen new high-rise buildings will be completed in 2015 alone.

Istanbul has changed in a myriad of ways over the last one-and-a-half centuries, but it still encapsulates the same paradox: being Western and not being so, to different extents, depending on where you find yourself. The Bosphorus, dividing Europe and Asia, also separates the city from itself. The city is like a broad, boundless ocean, deep and many-layered, quickly devouring the remaining open space and dense forests around it. From the hills of Çamlıca, the highest point on the Asian side, I still can’t see the whole city, but I can dimly make out where its edges must be. Compared to the sight before me, Robertson’s panorama captures a small town. In his time, Constantinople had not even reached one million inhabitants. Today, the city grows year by year with an influx of new people, and I wonder what the new flood of foreigners will bring upon this welcoming place.

The last coin designed by Robertson was minted in 1876. He had served four different sultans over the course of four decades when he officially retired on October 29, 1881—with more of his lifetime spent in Constantinople than in London. Ten days later, Robertson set off for Japan with his wife and three daughters. They reached Yokohama after a voyage of three months, joining Felice Beato, who had established himself there as a photographer. Robertson died on April 18, 1888, at the age of seventy-five. It took two months to the day for the news of his death to appear in the Levant Herald. He ended his life as a foreigner in a new land. He seems to have never seriously considered returning to England.

Translated from the German by Lori Lantz.