The drunken man is a living corpse.

—St. John Chrysostom, 390Exploring an Alternate Universe

Albert Hofmann discovers the effects of LSD.

A peculiar presentiment—the feeling that LSD-25 could possess properties other than those established in my first investigations—induced me, five years after the first synthesis, to produce it once again so that a sample could be given to the pharmacological department for further tests.

This was quite unusual; experimental substances as a rule were definitely stricken from the research program if once found to be lacking in pharmacological interest. Nevertheless, in the spring of 1943, I repeated the synthesis of LSD-25. As in the first synthesis, this involved the production of only a few centigrams of the compound.

In the final step of the synthesis, during the purification and crystallization of lysergic acid diethylamide in the form of a tartrate (tartaric acid salt), I was interrupted in my work by unusual sensations. The following description of this incident comes from the report that I sent at the time to Professor Stoll:

Last Friday, April 16, 1943, I was forced to interrupt my work in the laboratory in the middle of the afternoon and proceed home, being affected by a remarkable restlessness, combined with a slight dizziness. At home I lay down and sank into a not unpleasant intoxicated-like condition, characterized by an extremely stimulated imagination. In a dreamlike state, with eyes closed (I found the daylight to be unpleasantly glaring), I perceived an uninterrupted stream of fantastic pictures, extraordinary shapes with intense, kaleidoscopic play of colors. After some two hours, this condition faded away.

This was, altogether, a remarkable experience, both in its sudden onset and its extraordinary course. It seemed to have resulted from some external toxic influence; I surmised a connection with the substance I had been working with at the time, lysergic acid diethylamide tartrate. But this led to another question: how had I managed to absorb this material?

Because of the known toxicity of ergot substances, I always maintained meticulously neat work habits. Possibly a bit of the LSD solution had contacted my fingertips during crystallization, and a trace of the substance was absorbed through the skin. If LSD-25 had indeed been the cause of this bizarre experience, then it must be a substance of extraordinary potency. There seemed to be only one way of getting to the bottom of this. I decided on a self-experiment.

Smoking Haschisch, by Émile Bernard, 1900. Musée d'Orsay, Paris.

Exercising extreme caution, I began the planned series of experiments with the smallest quantity that could be expected to produce some effect, considering the activity of the ergot alkaloids known at the time: namely, 0.25 mg (one thousandth of a gram) of lysergic acid diethylamide tartrate. Quoted below is the entry for this experiment in my laboratory journal of April 19, 1943:

Self-Experiments

4/19/43 4:20: 0.5 cc of one-half promil aqueous solution of diethylamide tartrate orally = 0.25 mg tartrate. Taken diluted with about 10 cc water. Tasteless. 5:00: Beginning dizziness, feeling of anxiety, visual distortions, symptoms of paralysis, desire to laugh. Supplement of 4/21: Home by bicycle. From 6:00 to about 8:00 most severe crisis. (See special report.)

Here the notes in my laboratory journal cease. I was able to write the last words only with great effort. By now it was already clear to me that LSD had been the cause of the remarkable experience of the previous Friday, for the altered perceptions were of the same type as before, only much more intense. I had to struggle to speak intelligibly. I asked my laboratory assistant, who was informed of the self-experiment, to escort me home. We went by bicycle, no automobile being available because of wartime restrictions on their use. On the way home, my condition began to assume threatening forms. Everything in my field of vision wavered and was distorted as if seen in a curved mirror. I also had the sensation of being unable to move from the spot. Nevertheless, my assistant later told me that we had traveled very rapidly. Finally, we arrived at home safe and sound, and I was just barely capable of asking my companion to summon our family doctor and request milk from the neighbors.

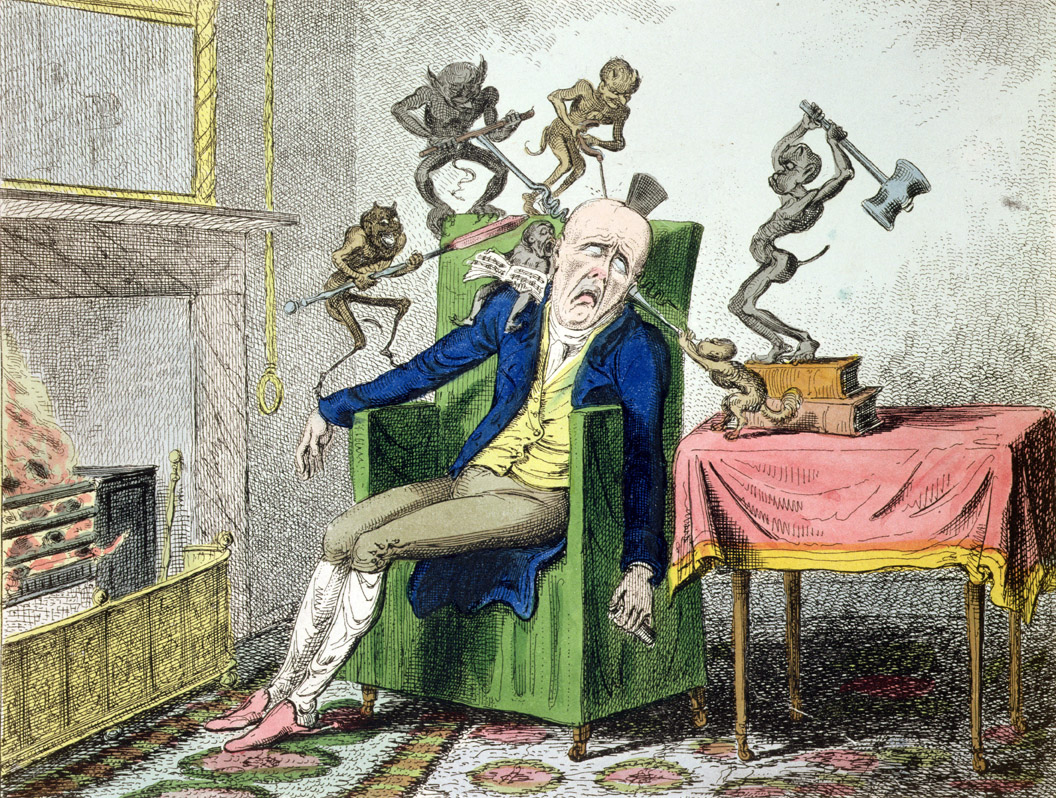

In spite of my delirious, bewildered condition, I had brief periods of clear and effective thinking—and chose milk as a nonspecific antidote for poisoning. The dizziness and sensation of fainting became so strong at times that I could no longer hold myself erect, and had to lie down on a sofa. My surroundings had now transformed themselves in more terrifying ways. Everything in the room spun around, and the familiar objects and pieces of furniture assumed grotesque, threatening forms. They were in continuous motion, animated, as if driven by an inner restlessness. The lady next door, whom I scarcely recognized, brought me milk—in the course of the evening I drank more than two liters. She was no longer Mrs. R, but rather a malevolent, insidious witch with a colored mask.

Even worse than these demonic transformations of the outer world were the alterations that I perceived in myself, in my inner being. Every exertion of my will, every attempt to put an end to the disintegration of the outer world and the dissolution of my ego, seemed to be wasted effort. A demon had invaded me, had taken possession of my body, mind, and soul. I jumped up and screamed, trying to free myself from him, but then sank down again and lay helpless on the sofa. The substance, with which I had wanted to experiment, had vanquished me. It was the demon that scornfully triumphed over my will. I was seized by the dreadful fear of going insane. I was taken to another world, another place, another time. My body seemed to be without sensation, lifeless, strange. Was I dying? Was this the transition? At times I believed myself to be outside my body, and then perceived clearly, as an outside observer, the complete tragedy of my situation. I had not even taken leave of my family (my wife, with our three children, had traveled that day to visit her parents in Lucerne). Would they ever understand that I had not experimented thoughtlessly, irresponsibly, but rather with the utmost caution, and that such a result was in no way foreseeable? My fear and despair intensified, not only because a young family should lose its father, but also because I dreaded leaving my chemical-research work, which meant so much to me, unfinished in the midst of fruitful, promising development. Another reflection took shape, an idea full of bitter irony: if I was now forced to leave this world prematurely, it was because of this lysergic acid diethylamide that I myself had brought forth into the world.

By the time the doctor arrived, the climax of my despondent condition had already passed. My laboratory assistant informed him about my self-experiment, as I myself was not yet able to formulate a coherent sentence. He shook his head in perplexity, after my attempts to describe the mortal danger that threatened my body. He could detect no abnormal symptoms other than extremely dilated pupils. Pulse, blood pressure, breathing were all normal. He saw no reason to prescribe any medication. Instead he conveyed me to my bed and stood watch over me. Slowly I came back from a weird, unfamiliar world to reassuring everyday reality. The horror softened and gave way to a feeling of good fortune and gratitude, the more normal perceptions and thoughts returned, and I became more confident that the danger of insanity was conclusively past.

Now, little by little, I could begin to enjoy the unprecedented colors and plays of shapes that persisted behind my closed eyes. Kaleidoscopic, fantastic images surged in on me, alternating, variegated, opening and then closing themselves in circles and spirals, exploding in colored fountains, rearranging and hybridizing themselves in constant flux. It was particularly remarkable how every acoustic perception, such as the sound of a door handle or a passing automobile, became transformed into optical perceptions. Every sound generated a vividly changing image, with its own consistent form and color.

Late in the evening my wife returned from Lucerne. Someone had informed her by telephone that I was suffering a mysterious breakdown. She had returned home at once, leaving the children behind with her parents. By now, I had recovered myself sufficiently to tell her what had happened.

Exhausted, I then slept, to awake next morning refreshed, with a clear head, though still somewhat tired physically. A sensation of well-being and renewed life flowed through me. Breakfast tasted delicious and gave me extraordinary pleasure. When I later walked into the garden, in which the sun shone now after a spring rain, everything glistened and sparkled in a fresh light. The world was as if newly created. All my senses vibrated in a condition of highest sensitivity, which persisted for the entire day.

This self-experiment showed that LSD-25 behaved as a psychoactive substance with extraordinary properties and potency. There was to my knowledge no other known substance that evoked such profound psychic effects in such extremely low doses, that caused such dramatic changes in human consciousness and our experience of the inner and outer world.

The Headache, by George Cruikshank, c. 1830.

What seemed even more significant was that I could remember the experience of LSD inebriation in every detail. This could only mean that the conscious recording function was not interrupted, even in the climax of the LSD experience, despite the profound breakdown of the normal worldview. For the entire duration of the experiment, I had even been aware of participating in an experiment, but despite this recognition of my condition, I could not, with every exertion of my will, shake off the LSD world. Everything was experienced as completely real, as alarming reality—alarming, because the picture of the other, familiar everyday reality was still fully preserved in the memory for comparison.

Another surprising aspect of LSD was its ability to produce such a far-reaching, powerful state of inebriation without leaving a hangover. Quite the contrary, on the day after the LSD experiment I felt myself to be, as already described, in excellent physical and mental condition.

I was aware that LSD, a new active compound with such properties, would have to be of use in pharmacology, in neurology, and especially in psychiatry, and that it would attract the interest of concerned specialists. But at that time I had no inkling that the new substance would also come to be used beyond medical science.

© 2009, Albert Hofmann. Used with permission of the Multidisciplinary Association for Psychedelic Studies (MAPS).

Albert Hofmann

From LSD: My Problem Child. Having received his PhD in chemistry at the age of twenty-three in 1929, Hofmann began work at Sandoz Pharmaceutical Laboratories, first synthesizing LSD-25 in 1938 while researching the stimulant effects of ergot fungus. Of his first contact with the substance, he said it was like “the same experience I had had as a child.”