I never even saw the use of the sea. Many a sad heart has it caused, and many a sick stomach has it occasioned! The boldest sailor climbs on board with a heavy soul and leaps on land with a light spirit.

—Benjamin Disraeli, 1827On Vacation

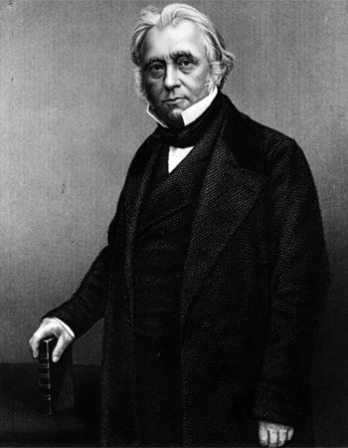

Charles Dickens hits the beach.

In the autumn, when the great metropolis is so much hotter, so much noisier, so much more dusty or so much more water-carted, so much more crowded, so much more disturbing and distracting in all respects than it usually is, a quiet sea beach becomes indeed a blessed spot. Half-awake and half-asleep, this idle morning in our sunny window on the edge of a chalk cliff in the old-fashioned watering place to which we are a faithful resorter, we feel a lazy inclination to sketch its picture.

The place seems to respond. Sky, sea, beach, and village lie as still before us as if they were sitting for the picture. It is dead low-water. A ripple plays among the ripening corn upon the cliff as if it were faintly trying from recollection to imitate the sea, and the world of butterflies hovering over the crop of radish seed are as restless in their little way as the gulls are in their larger manner when the wind blows. But the ocean lies winking in the sunlight like a drowsy lion—its glassy waters scarcely curve upon the shore—the fishing boats in the tiny harbor are all stranded in the mud—our two colliers (our watering place has a maritime trade employing that amount of shipping) have not an inch of water within a quarter of a mile of them, and they turn, exhausted, on their sides, like faint fish of an antediluvian species. Rusty cables and chains, ropes and rings, undermost parts of posts and piles and confused timber defenses against the waves lie strewn about in a brown litter of tangled seaweed and fallen cliff which looks as if a family of giants had been making tea here for ages and had observed an untidy custom of throwing their tea leaves on the shore.

You would hardly guess which is the main street of our watering place, but you may know it by its being always stopped up with donkey chaises. Whenever you come here and see harnessed donkeys eating clover out of barrows drawn completely across a narrow thoroughfare, you may be quite sure you are in our High Street. Our police you may know by his uniform, likewise by his never on any account interfering with anybody—especially the tramps and vagabonds. In our fancy shops we have a capital collection of damaged goods, among which the flies of countless summers “have been roaming.” We are great in obsolete seals and in faded pincushions, and in rickety camp stools and in exploded cutlery, and in miniature vessels and in stunted little telescopes, and in objects made of shells that pretend not to be shells. Diminutive spades, barrows, and baskets are our principal articles of commerce, but even they don’t look quite new somehow. They always seem to have been offered and refused somewhere else before they came down to our watering place.

Ulysses and the Sirens, by Herbert James Draper, 1909. Ferens Art Gallery, Hull, England.

Yet, it must not be supposed that our watering place is empty, deserted by all visitors except a few staunch persons of approved fidelity. On the contrary, the chances are that if you came down here in August or September, you wouldn’t find a house to lay your head in. As to finding either house or lodging of which you could reduce the terms, you could scarcely engage in a more hopeless pursuit. For all this, you are to observe that every season is the worst season ever known and that the house-holding population of our watering place are ruined regularly every autumn. They are like the farmers, in regard that it is surprising how much ruin they will bear. We have an excellent hotel—capital baths, warm, cold, and shower—first-rate bathing machines—and as good butchers, bakers, and grocers as a heart could desire. They all do business, it is to be presumed, from motives of philanthropy—but it is quite certain that they are all being ruined. Their interest in strangers and their politeness under ruin bespeak their amiable natures. You would say so if you only saw the baker helping a newcomer to find suitable apartments.

We have a pier—a queer old wooden pier, fortunately, without the slightest pretensions to architecture, and very picturesque in consequence. Boats are hauled upon it, ropes are coiled all over it; lobster pots, nets, masts, oars, spars, sails, ballast, and rickety capstans make a perfect labyrinth of it. Forever hovering about this pier with their hands in their pockets, or leaning over the rough bulwark it opposes to the sea, gazing through telescopes which they carry about in the same profound receptacles, are the boatmen of our watering place. Looking at them you would say that surely these must be the laziest boatmen in the world. They lounge about in obstinate and inflexible pantaloons—that are apparently made of wood—the whole season through. Whether talking together about the shipping in the channel or gruffly unbending over mugs of beer at the public house, you would consider them the slowest of men. The chances are a thousand to one that you might stay here for ten seasons and never see a boatman in a hurry. A certain expression about his loose hands, when they are not in his pockets, as if he were carrying a considerable lump of iron in each without any inconvenience, suggests strength, but he never seems to use it. He has the appearance of perpetually strolling—running is too inappropriate a word to be thought of—to seed. The only subject on which he seems to feel any approach to enthusiasm is pitch. He pitches everything he can lay hold of—the pier, the palings, his boat, his house—when there is nothing else left, he turns to and even pitches his hat, or his rough-weather clothing. Do not judge him by deceitful appearances. These are among the bravest and most skillful mariners that exist. Let a gale arise and swell into a storm, let a sea run that might appall the stoutest heart that ever beat, let the light boat on these dangerous sands throw up a rocket in the night, or let them hear through the angry roar the signal guns of a ship in distress, and these men spring up into activity so dauntless, valiant, and heroic that the world cannot surpass it. Cavilers may object that they chiefly live upon the salvage of valuable cargos. So they do, and God knows it is no great living that they get out of the deadly risks they run. But put that hope of gain aside. Let these rough fellows be asked, in any storm, who volunteers for the lifeboat to save some perishing souls as poor and empty-handed as themselves, whose lives the perfection of human reason does not rate at the value of a farthing each: that boat will be manned as surely and as cheerfully as if a thousand pounds were told down on the weather-beaten pier. For this, and for the recollection of their comrades whom we have known, whom the raging sea has engulfed before their children’s eyes in such brave efforts, whom the secret sand has buried, we hold the boatmen of our watering place in our love and honor, and are tender of the fame they well deserve.

So many children are brought down to our watering place, that when they are not out of doors, as they usually are in fine weather, it is wonderful where they are put: the whole village seeming much too small to hold them under cover. In the afternoons you see no end of salt and sandy little boots drying on upper windowsills. At bathing time in the morning, the little bay echoes with every shrill variety of shriek and splash—after which, if the weather be at all fresh, the sands teem with small blue-mottled legs. The sands are the children’s great resort. They cluster there like ants, so busy burying their particular friends and making castles with infinite labor which the next tide overthrows, that it is curious to consider how their play, to the music of the sea, foreshadows the realities of their afterlives.

It is curious, too, to observe a natural ease of approach that there seems to be between the children and the boatmen. They mutually make acquaintance, and take individual likings, without any help. You will come upon one of those slow heavy fellows sitting down patiently mending a little ship for a mite of a boy, whom he could crush to death by throwing his lightest pair of trousers on him. You will be sensible of the oddest contrast between the smooth little creature and the rough man who seems to be carved out of hard-grained wood—between the delicate hand expectantly held out and the immense thumb and finger that can hardly feel the rigging of thread they mend—between the small voice and the gruff growl—and yet there is a natural propriety in the companionship: always to be noted in confidence between a child and a person who has any merit of reality and genuineness, which is admirably pleasant.

There are a few old used-up boatmen who creep about in the sunlight with the help of sticks, and there is a poor imbecile shoemaker who wanders his lonely life away among the rocks as if he were looking for his reason—which he will never find. Sojourners in neighboring watering places come occasionally in flies to stare at us and drive away again as if they thought us very dull; Italian boys come, Punch comes, the Fantoccini come, the tumblers come, the Ethiopians come; glee singers come at night and hum and vibrate (not always melodiously) under our windows. But they all go soon and leave us to ourselves again. We once had a traveling circus and Wombwell’s menagerie at the same time. They both know better than ever to try it again, and the menagerie had nearly razed us from the face of the earth in getting the elephant away—his caravan was so large and the watering place so small. We have a fine sea, wholesome for all people—profitable for the body, profitable for the mind.

Charles Dickens

From “Our English Watering Place.” When this essay appeared, Dickens had in the previous few years published Dombey and Son and David Copperfield; later in the decade he published Hard Times and A Tale of Two Cities. In a companion essay entitled “Our French Watering Place,” he judged that “the very neckcloths and hats of your elderly compatriots cry to you from the stones of the streets, ‘We are bores—avoid us!’” and “They believe everything that is impossible and nothing that is true.” He died at the age of fifty-eight in 1870.