Have you ever, looking up, seen a cloud like to a centaur, a leopard, a wolf, or a bull?

—Aristophanes, 423 BC

The Sorceress, by Bartolomeo Guidobono, c. 1690. Iris & B. Gerald Cantor Center for Visual Arts at Stanford University.

In September 1863, a local paper in Somerset, England, ran an article about a man and a woman from Taunton whose child had been stricken with scarlet fever. Depressingly common, a child suffering from the illness itself was not noteworthy—what made the news were the remedies proposed. Distraught, the parents had turned to a group of women for advice, and this “jury of matrons,” in the paper’s words, all agreed that there was no hope of survival. Instead, they suggested ways to prevent the child from “dying hard”: open all the doors, drawers, cupboards, and boxes in the house, untie any knots—perhaps in a shoelace, a curtain pull, or an apron sash—and remove all keys from their locks.

In 1707, Taunton had been the site of one of the last witch trials in England, and while the paper didn’t call these matrons witches outright, reactions among any urban readers who would have come across the story would likely have ranged from bemusement to dismay that ancient superstitions still persisted in England’s smaller towns. The household rituals suggested by these women contained a belief that stretches back thousands of years, a belief in “sympathetic magic,” a phrase coined in 1890 by anthropologist James G. Frazer in The Golden Bough—a mammoth study of magic, science, and religion. The sympathies involved were commonplace: everyday objects could affect human behavior and physical actions. By throwing open the doors and untying the knots, the Somerset jury of matrons were offering their best advice so that a “sure, certain, and easy passage into eternity could be secured.”

Ishtar, goddess of the heavens, love, and war, with crescent-moon crown and necklace, and lions and owls, Mesopotamia, c. 1775 BC. British Museum, London.

Miraculously, the child did not die. A few years later, a surgeon familiar with the case suggested that the women’s advice had inadvertently ventilated the home, and he celebrated this bit of “magical” intervention. (“Oh, that there were in scarlet-fever cases a good many such old women’s—such a ‘jury of matrons’—remedies!”) In his book, Frazer had a good deal more scorn for the matrons and their advice: “Strange to say, the child declined to avail itself of the facilities for dying so obligingly placed at its disposal by the sagacity and experience of the British matrons of Taunton; it preferred to live rather than give up the ghost.”

It’s a shame that we owe so much of our understanding of sympathetic magic to someone whose attitude toward magic was so, in a word, unsympathetic. In the time since its publication, The Golden Bough has influenced and inspired everyone from T.S. Eliot to H.P. Lovecraft, W.B. Yeats to Joseph Campbell. No one before Frazer had so exhaustively documented the wide variety of shamanistic, magical, and religious practices throughout the world, nor had anyone sought to so thoroughly synthesize them into a work regarding the basic structures of human belief. Yet for all its rigor, Frazer repeated a vicious refrain throughout: magic is a “spurious system of natural law as well as a fallacious guide of conduct,” “a false science,” as well as an “abortive” and “bastard” art.

Drawing from questionnaires sent to anthropologists, field workers, missionaries, and colonial administrators, Frazer analyzed a broad spectrum of magical rites and rituals—the preservation of hair and nail clippings, the destruction of images and effigies, the healing power of color—ultimately grouping them into two broad categories: the Law of Similarity, whereby “like produces like,” (a mutilated wax figure, for example, standing in for a hated person) and the Law of Contagion, in which “things which have once been in contact with each other continue to act on each other at a distance after the physical contact has been severed” (in which hair, nail clippings, or clothing once belonging to that person just might do the trick).

Sympathetic magic taps into a symbolic ordering of the world, where disparate objects and ideas can have unexpected correspondences and new potentials. This kind of magic reflects the order of our lives even as it seeks to gain mastery over that order. Its genius is its simplicity, which articulates a basic but all-encompassing explanation for human and natural events. With the proper gesture or carved totem, all of heaven and earth is in the hands of the magician. Sympathetic magic is easy to understand, requires no real training, and is catholic in its application; anyone who can tie knots or who can fashion a wax doll can employ it, from kings to their illiterate peasant subjects.

Perhaps this is why Frazer disdained sympathetic magic: by its very simplicity, scholars saw in it something juvenile and unsophisticated. Frazer describes the rainmaking ceremonies of an unspecified tribe of American Indians as involving a “sort of childish make-believe,” whereby one seeks to establish a sympathy with rain by making oneself wet, and fertility rites are “relics of an age of childish ignorance,” practiced by those who don’t understand modern obstetrics.

It’s no accident that the study of magic and ritual flourished during the wane of the British empire; the beliefs of native cultures were collected and studied so they could be corrected. The study of magic was important, the ethnologist E.E. Evans-Pritchard would later explain, “not only for the anthropologist but also for the colonial administrator and missionary, if they wish to show to the peoples whom they govern and teach that they understand their notions about right and wrong.” For some, the main reason for studying sympathetic magic was to eradicate it.

For all its erudition and analysis, The Golden Bough has for more than a century helped cement the idea that magic is inappropriate, wrongheaded thought. Yet what separates magic from religion or science is not its methodology—Frazer himself notes that it “is therefore a truism, almost a tautology, to say that all magic is necessarily false and barren; for were it ever to become true and fruitful, it would no longer be magic but science”—it’s that ordinary people can do it, transforming their lives with the ambitious power of everyday thought.

Disdain for sympathetic magic, particularly for its simplicity and its universal application, can be traced back two millennia before Frazer and his peers. In the Laws, Plato’s Athenian Stranger complains of the gullibility of the citizenry, lamenting that “it would be a labor lost to bring conviction to minds beset with such suspicions of each other, to tell them, if they should perchance see a manikin of wax set up in a doorway, or at the crossroads, or at the grave of a parent, to think nothing of such things, as nothing is known of them for certain.” Even aware of the fallaciousness of such belief, Plato seemed hesitant to ignore it altogether, and the Laws goes on to advise that while white magic is perfectly acceptable, any professional diviner or prophet suspected of “doing mischief by the practice of spells, charms, incantations, or other such sorceries” be put to death, while an amateur practitioner should pay a fine.

Far more caustic was Horace in his Satires, who wrote of a block of wood carved into a statue of Priapus, who then has to suffer the rituals of two witches, Candidia and Sagana:

They held two dolls, one made of wool, the other

Of wax. The first was big and seemed to threaten

The one who had its waxen arms upraised

In supplication like a slave afraid

Of death.

The poem continues in this vein, speaking ominously of black magic and terrifying rites, though all of this is suddenly undercut when the statue’s “figwood ass” looses a fart:

The hags ran off in panic, back

To town. You should have seen Candidia.

Her teeth fell out. Sagana’s wig flew off

Her head. The magic herbs and voodoo charms

They’d dropped lay scattered all across the ground.

It was enough to make you roar with laughter.

If Plato and Horace offered a bemused, if tolerant, attitude toward wax figures and other forms of sympathetic magic, the Christian revolution would bring a much harsher response. By the fourth century, Christian emperors like Constantius II and Theodosius began passing increasingly strict laws regarding the practice of pagan magic—first sacrifice was banned, then the old temples were closed, and finally death was prescribed for anyone who persisted carrying out the old rites.

Why then, despite logical reasoning, despite ridicule, despite threats of violence and execution, have so many persistently clung to sympathetic magic? Pliny the Elder, who himself noted one could barely “preserve one’s seriousness” in describing folk remedies based on sympathetic magic, nonetheless offered a succinct theory on why magic continues to fascinate. He wrote that magic masquerades “under the plausible guise of promoting health”; further, it has “added all the resources of religion”; and finally, “it has incorporated with itself the astrological art, there being no man who is not desirous to know his future destiny, or who is not ready to believe that this knowledge may with the greatest certainty be obtained, by observing the face of the heavens.” Sympathetic magic promises to transform the things that matter most, and which people have the least control over—the weather and crops, disease and fertility, and the ever-present specter of unexpected death. Those who felt themselves most acutely at the mercy of these forces were those who gravitated toward it.

A good Christian had no need to fear death or calamity, and no need to ward them off with magical charms. A popular text, first published in the mid-fifteenth century, was Ars Moriendi, “The Art of Dying Well,” which taught that death was a thing to prepare for and look forward to. Increasingly, sympathetic magic—particularly the rituals practiced by the poor, the elderly, and the female—became synonymous with black magic and witchcraft. In fourteenth-century France, Anne-Marie de Georgel was accused of frequenting “the gallows trees by night stealing shreds of clothing from the hanged, or taking the rope by which they were hanging, or laying hold of their hair, their nails or flesh.” Another woman convicted in the same trial, Catherine Delort, who confessed under prolonged torture to making wax figures in the likeness of her aunts and burning them over a fire, “so that their unfortunate lives wasted away as the waxen figures melted in the brazier.”

As was common in witch trials, both Georgel and Delort were accused of using magic for material gain. (Delort, it was claimed, was trying to gain an inheritance from her family.) Magic was ungodly because it was impatient, a shortcut to health and wealth. The Malleus Maleficarum, an infamous 1486 handbook for prosecuting the heresy of witchcraft, complained in particular of “weak” women who “find an easy and secret manner of vindicating themselves by witchcraft.” God’s plan was all-encompassing, but often inscrutable, and the prevailing belief was that those who couldn’t put their faith in it instead turned to the quick fix of magical rites. In 1580, Jean Bodin defined a sorcerer as “one who by commerce with the Devil has a full intention of attaining his own ends.” In 1926, perhaps the last great true believer in witches, vampires, and werewolves, the theologian Montague Summers, likewise claimed that witches were above all “avowed enemies of law and order, red-hot anarchists who would stop at nothing to gain their ends.” Magic seemed to offer what the Church, with its emphasis on enduring suffering and povery could not—wealth and power—but this was only a small part of the picture.

The Magic Carpet, by Viktor Vasnetsov, 1880. Nizhny Novgorod state Art Museum, Russia.

Take, for example, the tragic series of events in North Berwick, Scotland, in 1590. There, a deputy bailiff named David Seaton became suspicious of his maid, Geillis Duncan, and later determined that she was sneaking out at night, whereupon she “took in hand to help all such as were troubled or grieved with any kind of sickness or infirmity, and in short space did perform many matters most miraculous.” At no point was Duncan accused of seeking material gain or of pursuing her own selfish intentions, but all the same, Seaton accused her of witchcraft, and had her tortured for some time before she finally admitted to it. In her confession, Duncan named a dozen or so other co-conspirators, among them a midwife named Agnes Sampson, known as the “eldest witch of them all,” who was likewise tried and tortured.

Sampson’s case became noteworthy because it attracted the attention of James VI, then king of Scotland and later, as James I, of Great Britain, who took a personal interest in the proceedings, even examining Sampson in person. James had recently come from Copenhagen, where he had married his queen, Anne of Denmark. The Danish capital was abuzz with whispers of witchcraft, and when James and Anne’s ship ran into unexpected storms on the voyage back to Scotland, he became convinced that it was due to witchcraft. Under enough torture, Sampson confessed that she had obtained a piece of linen worn by the king, and that she had coated it with the venom of a black toad, because the Devil hated the king, “by reason the king is the greatest enemy he hath in the world.” James, satisfied he’d caught the culprit and stopped the conspiracy, had her hanged and then burned.

James went on to write his own book on witchcraft in 1597, in which he further cemented the idea that witches can “raise storms and tempests in the air, either upon sea or land”—a book which may in turn have inspired Shakespeare’s treatment of witches in Macbeth a few years later; seeking revenge on a sailor’s wife, the first weird sister is given winds by her colleagues, boasting “I’ the shipman’s card./I’ll drain him dry as hay.”

The conviction that witches were behind dangerous storms and other unexpected perils highlights a curious reversal that had taken place with regard to sympathetic magic. If it had once been used as a ward against uncertainties, against the caprices of nature and sudden death, now many saw it primarily as a cause of these dangers. (The Malleus Maleficarum warns that witches “can also, before the eyes of their parents, and when no one is in sight, throw into the water children walking by the waterside; they make horses go mad under their riders.”) These primal anxieties, of course, hadn’t gone away, and James, afraid of drowning at sea, certainly hadn’t yet learned the Christian art of dying well.

Such subtleties were no doubt lost as the crush and waste of humanity that was the European witch panic took on a logic and inertia of its own. After all, it was good business. Agnes Sampson’s torture and execution, like most witch trials, wasn’t cheap, employing judges, scribes, bailiffs, jailers, and executioners—each of whom had a financial stake in further trials. The trial record of Suzanne Gaudry, executed in 1652 in Ronchain, France, notes that each member of the court was to be paid 4 livres, 16 sous, while the soldier who accompanied her to Roux for the trial was to be paid 30 livres. Around 1593 in Trier, the scholar Cornelius Loos quipped that witch persecutions were a new kind of alchemy, whereby “gold and silver [were] coined from human blood”—before all his books were burned and he was forced to publicly recant ever having said such a thing.

As the world was becoming more ordered and codified via patriarchal religion and a burgeoning system of capitalism, magic was seen as a threat because it circumvented these structures: it offered a life outside the authority of the Church and the hierarchies it had carefully cultivated. Little had changed; people still felt powerless in the face of nature, but now instead of turning to magicians, they blamed them. The Church, after all, rarely attacked sympathetic magic on the grounds that it was empirically fallacious or ineffective—rather, it was a rival source of power. Among the many scandalous aspects of witches’ sabbaths as they were popularly depicted was the commingling of social classes: women—and increasingly men—of all walks of life, from peasants to the aristocracy, all were equal at the Midnight Mass. This vision of a dark Utopia was as threatening—if not more so—than any of the black rites practiced therein.

In 1608, witch hunter William Perkins included among his condemned not only witches who “kill and torment,” but those who “do not hurt but good,” who “do not spoil and destroy, but save and deliver,” concluding that “it were a thousand times better for the land if all witches, but specially the blessing witches, might suffer death.” Healing magic, the kind that might be performed by believing midwives, was seen as bad, if not worse, than the dark arts. The Malleus Maleficarum notes “that in all these matters, witch midwives cause yet greater injuries, as penitent witches have often told to us and others, saying: no one does more harm to the Catholic faith than midwives.” Men were terrified of female healers, especially midwives, since childbirth was of such massive consequence and so completely out of the control of men. The work of midwives was at the center of a mysterious realm of women, and its secrets bred longstanding professional jealousy.

This changed slowly, starting in the late eighteenth century, as most countries began a gradual transition from midwife-assisted home birth to hospital birth attended by doctors. But if we now see this as something like progress, at the time it was met with utter terror—after all, even as scientific inquiry and empiricism broke free of centuries of received doctrine and faith, there was still much that science couldn’t explain.

To ensure the adoration of a theorem for any length of time, faith is not enough; a police force is needed as well.

—Albert Camus, 1951No one in Vienna in 1840 could explain, for example, why, of the general hospital’s two free maternity clinics, the patients at the first had a mortality rate from puerperal fever of 10 percent, while at the second, seemingly identical clinic, the mortality rate was rarely above 2 percent. This would have been particularly confusing to medieval witch-hunters, since the second clinic was staffed by midwives, whereas the first was operated by male doctors. Nevertheless, women were so terrified of being admitted to the first clinic that some gave birth in the street rather than be admitted there.

Among those desperate to make sense of this fatal discrepancy was the young Ignaz Semmelweis, appointed assistant at the Vienna obstetric clinic in 1846. Appalled by the senseless waste of life and the seeming disinterest of the medical professionals around him, Semmelweis ultimately realized that the women in the maternity ward were being infected by what he called “cadaverous particles,” still clinging to the hands of the doctors fresh from dissection (the midwives at the second clinic did not do dissections, and did not come into regular contact with cadavers). Instituting a regime of hand washing with chlorinated water, Semmelweis lowered the mortality rate at the first clinic to levels equal to the second clinic almost overnight.

Nevertheless, he was roundly criticized for his methods, which critics claimed were grounded in assumption, never rigorously tested, nor based on any explanatory theory. Semmelweis, in short, was accused by those around him of performing something close to ritual magic: “cadaver particles” were just another name for Frazer’s Laws of Contagion, the ability of a nefarious object to affect innocent victims from great distances. Semmelweis lost his position a few years later, and in disgrace moved to Budapest; in 1865 he was institutionalized against his will in a barbaric asylum, where he died two weeks later.

Despite his tragic end, Semmelweis’ critics were right in many ways. Semmelweis didn’t know why what he was doing worked, he only knew that it worked. He never wavered from his convictions, because the alternative—to wait for Louis Pasteur and Robert Koch to articulate the germ theory of disease—might have meant the deaths of hundreds more of his patients. “My doctrines,” he proclaimed, “exist to rid maternity hospitals of their horror, to preserve the wife for her husband and the mother for her child.” Semmelweis has consistently bedeviled historians of science because he was doing magic, and he was right. His story may prove Frazer’s claim that all effective magic is just science in disguise, but that doesn’t make it any less valid. While we wait for science to catch up, we sometimes still cling to magic because it’s the only way we can tell ourselves that the world makes sense.

Perhaps this explains why a belief in sympathetic magic—irrational, superstitious, glorious—continues unabated in our hyper-rationalist age. If anything, the ascendancy of science has clarified these beliefs, and the degree to which we’re willing to cling to them despite a cognitive awareness of the fallacious nature of magic. In the past few decades, celebrity and sports memorabilia have become big business; at auction sites like gottahaverockandroll.com, one can bid on all manner of ordinary items that have been imbued with the proximity of the famous: the site boasts of having auctioned John Lennon’s talisman necklace, worn on the cover of his and Yoko’s Two Virgins album, for a record $528,000, and recently auctioned a small amount of hair collected from Michael Jackson’s stay at the Carlyle Hotel, bought by a gambling website with an eye toward turning it into a roulette ball. “Together,” onlinegamblingpal.com proclaims, “we can ensure Michael Jackson continues to rock and ‘roll’ forever,” while meanwhile, the Hard Rock Cafe continues to build on its successful business model of serving mediocre food magically enhanced by its close proximity to the guitars of the famous suspended above diners’ heads. Sympathetic magic was once employed to protect us from chaos, to offer a measure of control over the caprices of nature. Now it offers a chance of escape, however fleeting, from a world of hierarchy and order. In a world where each of us is assigned a place, to hold Elvis Presley’s shirt is, for a moment, to capture some of the magic of Presley’s life, to inhabit a life other than one’s own. It’s a way of making it through life.

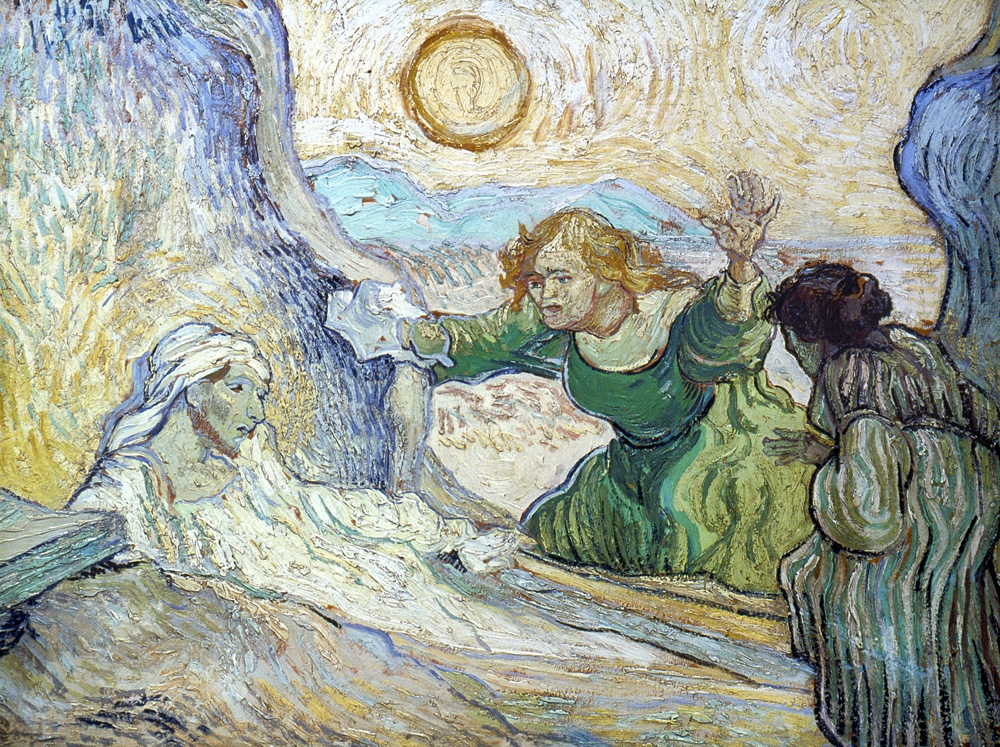

The Raising of Lazarus (After Rembrandt), by Vincent van Gogh, 1890. Van Gogh Museum, Amsterdam.

Or a way of facing death. In the wake of her husband’s death, Joan Didion repeatedly caught herself trying to employ magic as a means of coping with the loss. She describes being unable to give away certain of his possessions, as though their contagious power might yet bring him back. “I was thinking as small children think,” she writes, “as if my thoughts or wishes had the power to reverse the narrative, change the outcome. In my case this disordered thinking had been covert, noticed I think by no one else, hidden even from me, but it had also been, in retrospect, both urgent and constant.”

Didion fought the impulses of this backward thinking by research, by science, by clear-headed rational thinking: “In time of trouble, I had been trained since childhood, read, learn, work it up, go to the literature.” For Didion, mourning lay precisely in this struggle, rational versus the magical, the working through of grief versus the hope against hope that death can be overcome. Our attitudes toward sympathetic magic haven’t really changed, though this battle—the age-old conflict between logical authority and childish magic—has for many of us, like Didion, become internalized, the two halves of our brain working at odds with each other. There’s nothing particularly disordered or childish in any of this. We turn to magic because sometimes it’s all we have; in the face of things beyond our control, magical thinking remains that last bit of hope that we’ll always have at our disposal.