Every man sees in his relatives, and especially in his cousins, a series of grotesque caricatures of himself.

—H.L. Mencken, 1919A Harmony in Living

Happy families are indeed all alike in calling forth the best of their members’ humanity.

By Garret Keizer

Everhard Jabach and His Family, by Charles Le Brun, c. 1660. The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Mrs. Charles Wrightsman Gift, 2014.

Two-edged sword

Even without a biography to go on, we would know that Leo Tolstoy had a troubled household and a blinding ego by the ridiculous line with which he begins Anna Karenina: “Happy families are all alike; every unhappy family is unhappy in its own way.” In fact, as anyone can tell you whose experience of the world goes beyond the reading of nineteenth-century Russian novels, the truth is quite the reverse. Take the safer course of confining Tolstoy’s generalizations to marriage, and observation still stands them on their heads. Unhappy marriages are all alike, with their interchangeable spats and infidelities, their tritely plotted scenarios of aggression and neglect. It is the happy ones that vary, some couples inseparable except with deep distress, others madly in love across months and miles of absence; some virtually and contentedly celibate, others laughing uproariously between orgasmic shrieks at pornography’s pitiable innocence; some matches made between couples whose chromosome pairs differ, others of more recent vintage with chromosomes exactly matched, while eclectic, nonmonogamous arrangements show up throughout history and around the world.

What is true of marriages and families is true of most things really: the more viable they are, the more diverse. The moribund tends to the monochrome. Thomas Aquinas said that the angels are so differentiated as to be each one a distinct species, and you don’t have to be a Thomist or believe in angels to grasp what he was getting at. Swap a couple of mustaches and there’s little to distinguish a Hitler or a Stalin from Attila the Hun.

But we must give the count his due on at least two points. Happy families are indeed all alike in calling forth the best of their members’ humanity, in teaching them the arts of peace and kindness. If Waterloo was won on the playing fields of Eton, as the Duke of Wellington is supposed to have said, the peace was signed on the tablecloths of the players’ happiest homes. Blessed are the peacemakers, for someone has cared enough to make them lunch. Blessed am I, for it is only by virtue of being a fortunate son, brother, husband, and father that I have managed to be a little better than a pig.

Only a little better, though, because of the second likeness on Tolstoy’s side of the argument: the tendency of happy families to hold their members’ humanity in check. My family comes first, you see. Those seeking a more generous embrace have often forborne to start families (Florence Nightingale), or forsaken their families (Buddha), or drawn others away from their families (Jesus), or been inadequate providers for their families (Karl Marx), or made a miserable mess of their families (Tolstoy). “Sex kills,” Joni Mitchell tells us, pointing to its less hallowed aspects, but the hallowed ones can kill us too. Don’t forget the Sopranos and the Corleones before them. Don’t forget Charlie Manson, who knew exactly what he was doing and what he was about to do when he dubbed his outfit “The Family.”

Destroyer of cities

One of the scariest print ads I ever saw—scarier than Helter Skelter but subtly in the same vein—showed a chemical engineer (male in some versions, female in others) posing with his or her young child. I forget the exact wording of the text and the name of the sponsor (this was years ago), but I remember the message well. In so many words it said, “I too have a child, so you needn’t worry about me knowingly polluting our environment and compromising the future of life on earth.” I still get chills when I think of it.

I get chills because I know of nothing more likely to cause an otherwise ethical engineer to turn a blind eye to preventable pollution than a child who is the apple of his eye and who needs braces, college tuition, and a dad who can hold down a job. Whatever you say, boss. If parsimony and racism helped to turn Katrina into a disaster, love also must have lent a hand, the love of a parent more willing to sign off on a shabby levee than celebrate a lean Christmas. Of course this is nothing new.

The Gilder Family, by Augustus Saint-Gaudens, c. 1883–84. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of David and Joshua Gilder.

Consider The Odyssey, for example. I am enough of a Sopranos-style daddy not to be too bothered that Odysseus kills the suitors who have camped out in his house. In his shoes, I might have done the same thing, lack of prowess preventing me more than scruple. What bothers even me, however, is that his homeward-bound adventures begin with a raid on a coastal town during which he and his men seize livestock and women. In comparison, the suitors of Ithaca are gentlemen callers, boors and bullies to be sure, but none of them presumes to carry off Penelope folded and kicking over his shoulder. I want to believe that Homer has bookended his story purposefully in this way, so that like Jacob in the Bible, who dupes his father and brother only to be duped by his father-in-law Laban in turn, Odysseus will come to self-awareness once the shoe of rapine is on the other foot. Dream on. Noting the flocks he’s lost to the freeloading suitors after his servants have scraped their lifeblood off the floor, Odysseus counsels Penelope not to worry: “They’ll be replenished: scores I’ll get on raids.” He has learned nothing, and his wife does not say, “Give it a rest!” I imagine she’s already thinking up little projects for any two-legged chattels included in the booty, beginning with that ugly weed patch behind the hall. She and her husband are far too clever not to recognize that a slave is deprived of the very pleasures he toils to create, but they are too much people of their age, or should I say too much spouses and parents of any age, not to chalk up the injustice as one of the cruel but inescapable facts of life. We fly the family to Disney World and perhaps reflect for a moment that the man pushing his broom through the streets of the Magic Kingdom is not likely to enjoy a comparable privilege. We admonish our littlest not to throw her candy wrapper on the ground, but we do not go much further.

Choosers and losers

Still, we hope to go further, to take the benefits of family life and enlarge them to include persons beyond our households. “The whole human family,” we say, and hope the phrase catches on. But will it signify much if it does? Are we possibly clinging to a dead metaphor?

If anything distinguishes the family of our time and culture from families elsewhere and in times past, it is the element of choice. Unlike our predecessors and cousins in warmer climes, we choose our spouses; we choose whether we will have children, and how many, and when they will be born. Few of us would want it otherwise. If we wish, we can even choose the sex of our children and within a generation may be trying to choose their SAT scores and the shape of their chins. We ascribe this range of choice to the scientific advances and liberalization of modern societies, a fair enough assessment, though it might as easily be ascribed to the totalitarian grip of consumer capitalism. When Smokey Robinson’s mamma told her bachelor son, “You better shop around,” she could hardly have predicted how far shopping was going to go.

The first stop was predictable enough. Logically, the right to be choosy about family matters includes the right to dissolve one’s existing family and reconstitute it on one’s own terms, or on mutually agreed upon terms: you’ll live with your dad and your sister will come with me. The ancient, tragic condition of being “stuck” with people you never liked or have come by stages not to like has been made less sticky. “I think the biological family is especially compelling to us because it is, in fact, very arbitrary in its composition,” writes a marvelously cheeky Marilynne Robinson, flouting our disdain for the “arbitrary” and further noting that “the charm and the genius of the institution…implies that help and kindness and loyalty are owed where they are perhaps by no means merited.” The key word here is “implies”; the key question: what happens when our conception of the biological family implies no such thing?

What happens, in other words, when we decide to be as choosy about the human race as we have become about the biological family? Of course we have always been choosy in practice, else there would be no such thing as a whites-only country club, but it takes no great imagination to foresee a time when we might subscribe to the same discrimination as a matter of progressive principle, when there will be different planets for different categories of people just as we now have different bars and television channels for distinct marketing groups. Even when we undertake to “celebrate diversity,” one detects a whiff of preciousness, the sprawling harvest of humanity reduced to an upscale farmer’s market. I’ll take a couple of black West Indians, with the dreadlocks still on if you have that, and a few Hispanics would be nice, fresh and in season—though we certainly wouldn’t want our salad overwhelmed by a whole bunch of them, especially the sort who pick the greens.

No one studies history for long or at any depth without developing a sense of irony, and this may be one of the most significant ironies of our time: that having at long last come to the inescapable conclusion that we are all members of the “Human Family,” the idea of family should have become too weak to carry us home.

The Botto family picnic

Be that as it may, I must be a confirmed “family man,” for within the constellation of my personal heroes I find heroic families. Admittedly some of them are merely the kin clusters of admired individuals, but some are heroic in their own right. Our adult daughter was fond of the Laura Ingalls Wilder books as a child; her mother and I came to love them along with her, and Pa and Ma Ingalls still weigh in on family discussions around the table, Pa ready to embrace the future with his new iPhone, Ma and Mary dubious, and tweeting little Laura reminded yet again why she’s a daddy’s girl. I also like the Adams, John and especially Abigail, as well as the Addams, Gomez and Morticia, the latter pair from a TV show popular in my childhood and based on an equally popular series of New Yorker cartoons. (I grew up when even low culture was relatively high.) “They’re creepy and they’re kooky, mysterious and spooky,” the show’s theme song declared, and lest we be slow to see ourselves in the description, nudged us closer by throwing in “altogether ooky” for good measure. In a less conventional vein, I love the inchoate family that begins to coalesce in Kent Haruf’s novel Plainsong and the motley crew of dependents in Dr. Johnson’s house. More on Johnson later.

For now let us praise not-so-famous men, and women too, in the persons of Maria and Pietro Botto. In 1908, after fifteen years of toil in the Paterson textile mills, the Bottos moved from West Hoboken, New Jersey, purchased land in Haledon, then a rural suburb on the trolley line, and built a concrete block-and-clapboard tenement house, occupying the ground floor and renting rooms at the top. They planted a grape arbor and, I assume, made wine. They had four daughters, all of whom married and set up housekeeping in separate apartments of the house. One of these daughters would apply for a job using an alias, fearful that the name Botto might nix her chances of employment. Her fears were not unfounded.

In 1913 the Paterson textile workers went on strike, demanding an eight-hour day and safer working conditions. With a promise of protection from Haledon’s socialist mayor William Brueckmann, Maria and Pietro offered their house and its surrounding property as the site for a rally of more than twenty thousand striking workers, consisting of nine tightly knit ethnic groups, who assembled in their Sunday clothes to hear such IWW (Industrial Workers of the World) luminaries as Carlo Tresca, “Big” Bill Haywood, and Elizabeth Gurley Flynn address them from the upper story of the Bottos’ front porch.

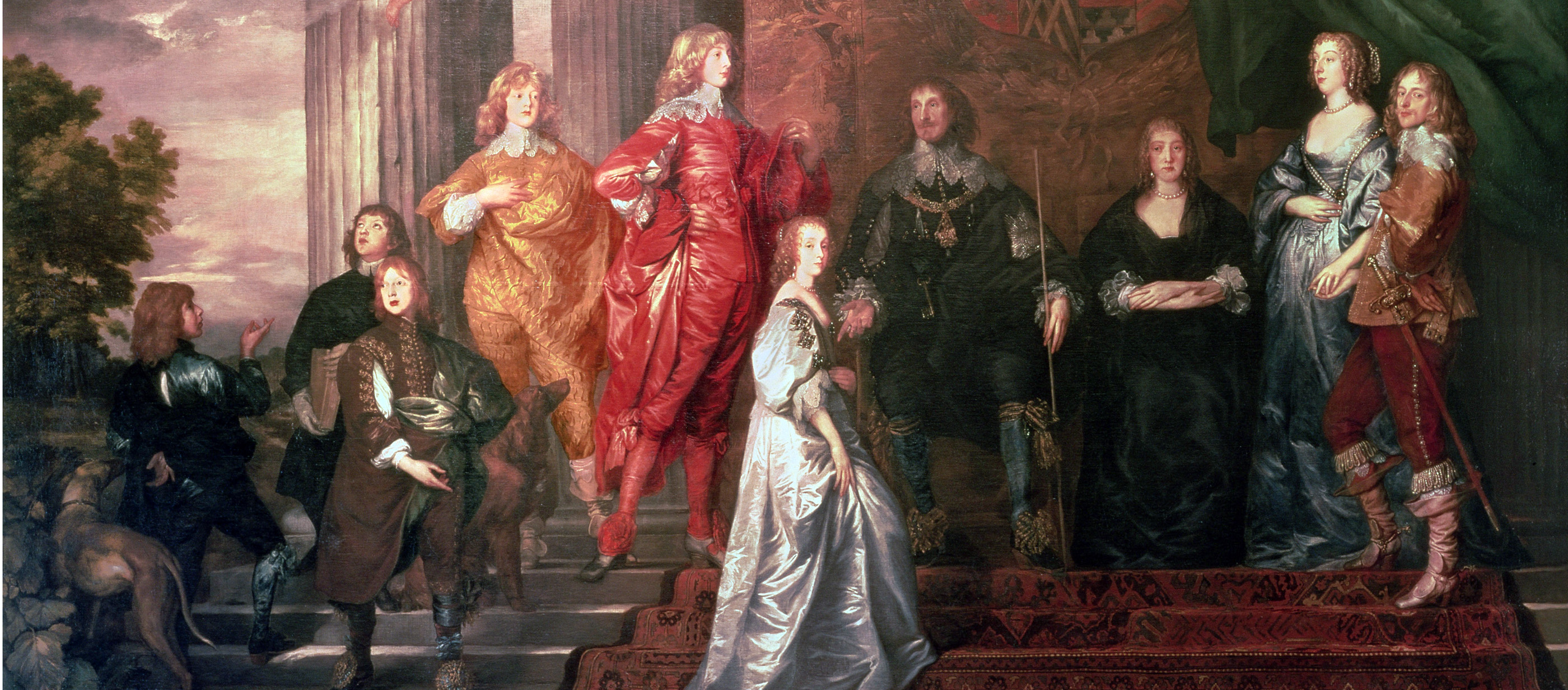

Philip Herbert, Fourth Earl of Pembroke, and His Family, by Sir Anthony van Dyck, c. 1635. The Earl of Pembroke’s Collection.

Once upon a time there were a daddy and a mommy named Pietro and Maria. They came from Italy, where Pietro used to paint the insides of churches. In America they built a house and planted a grapevine and had four brave and lovely daughters. One day they decided to have a picnic. “Let’s invite twenty thousand of our friends!” said Maria. “Hooray!” said Pietro and clapped his hands. Then they sang a song they loved called “The Internationale.”

Larger than life they were, “like lesser gods,” to use the title of Mari Tomasi’s all-but-forgotten novel about their granite-working Italian comrades farther to the north. I am looking at a photograph of daughter Eva Botto, proud, solid, and swarthy; she stands behind the seated figures of sister-in-arms Mary Gallo and the Wobbly agitator Elizabeth Gurley Flynn (not to be confused with Helen Gurley Brown), who fathoms the camera with her dark sober eyes. Each presents us with the image of a strong woman, not in our revisionist sense of the term, which if Ambrose Bierce were still alive he might define as a lap dancer who insists on ordering her own drink whenever a man insists on buying her one. These women have their own wine to drink, thank you, and the grapes of wrath are ripening behind them.

That arbor is gone now. The Bottos’ house has been preserved as the American Labor Museum, a registered National Landmark. I also like to think of it as the American Family Museum, though the associations of museum trouble me in both cases. This last Father’s Day, my wife and daughter ordered me a box of notecards from the museum shop and an illustrated history of Haledon, which happens to be my wife’s hometown, with pictures of the Bottos and the Paterson strike. Occasionally I will call the place myself, always relieved when someone is there to answer the phone.

The house that Dr. Johnson built

If the Bottos serve as an example of a conventional family willing to stretch out its arms in a larger embrace, Samuel Johnson’s human “menagerie,” as one contemporary called it, presents us with a case of altruism stretching toward family. A widower in the years when this menagerie flourished, Johnson had famously remarked that while marriage has many pains, celibacy offers no pleasures. In his fabled house in London’s Gough Square, Johnson must sometimes have felt that he had opted for the worst of both worlds, celibacy plus all of the pains of cohabitation, including a few from hell.

At one time his amalgamated household included a blind woman poet (who waited up for him to come home from his late-night rambles and take a cup of tea, and whose verses he managed to have published), a widowed companion of his late wife (who prevailed upon him to take in her thirty-year-old daughter as well), an irascible and dubiously reformed female prostitute, a freed African slave (who would eventually acquire an English wife and children, who also lived in the house for a time), and a down-at-the-heels doctor to the poor, who shared Johnson’s habit of sleeping late and would join his patron for a noon breakfast in similar dishabille. The late breakfasts with Dr. Levit and the late-night teas with Anna Williams were brief respites from continual squabbling; nearly every one of Johnson’s lodgers resented at least one of the others. Frank Barber, the emancipated slave and no favorite of Miss Williams, eventually left home and enlisted on a ship, little knowing what awaited him there and gaining his release only after Johnson’s tireless intercessions. This episode was the occasion for Johnson’s remark that being on a ship was like being in a jail with the risk of being drowned thrown in, and that one’s company in jail was frequently of a better quality than the sort to be found on a ship. His household can appear to us as a typical ship’s company appeared to him, though like a ship his household helped him stay emotionally afloat.

He had often wanted for affection in his life, even in the bosom of more traditional family arrangements. His father was given to melancholy and his mother no match for her intellectually precocious son. (When she scolded him as “a puppy” once, he replied by asking if she knew what a puppy’s mother was called.) His own marriage to a woman almost twenty years his elder, though not without love on both sides, seems to have been unhappy, marked by long periods of absence on his part and marred in its last years by his wife’s addictions. They had no children.

My father! The sun is my father, and the earth is my mother, and on her bosom I will recline.

—Tecumseh, 1810Later on, while still maintaining his household of dependents, he took refuge with a well-to-do younger couple by the name of Thrale. Hester Thrale became Johnson’s confidant, his first biographer, and perhaps (as suggested by some letters) his closet dominatrix. Even if the last of these was not literally so, it was true enough figuratively in that Johnson seems to have exchanged the patron’s role he played with Barber and Williams for that of Hester’s needy dependent. The Johnson we love best, if we love him, is in his house drinking tea with Williams and Levit; the Johnson we love least is begging a widowed Hester Thrale not to throw her life away by marrying her daughter’s Italian singing teacher—which is to say, forbidding her to have the tender regard that her philandering first husband had denied her and that Johnson himself had longed for all his life.

Aside from that longing, what I find most interesting about Johnson’s surrogate families is the way in which their unconventional arrangements lead him willy-nilly to the familiar themes of family drama, even television family drama. The prodigal son, the jealous sibling, the futile attempt to launch a poor relation on the right foot, and the equally futile bid to be pleasured on demand (Hester seems to have pulled the plug on the bondage stuff)—none of this is new. Johnson was a conservative, not in the free-market sense we think of now (he distrusted the mercantile “Whig dogs”), but in the older sense of someone who believes that humanity does not evolve so much as it endures, that while monarchy has many pains, republicanism might prove to have no pleasures. I suspect that some of this conservatism came from his experience of family, from the intractability of its givens no matter how experimental its forms. And if his conservatism goes soft on certain issues (he hated slavery and upheld the right of the people to cut off a tyrant’s head), that may have come from the same experience. Tradition be damned—we must get poor Frank off of that miserable ship.

Till we have built Jerusalem

Not least of all because I have a daughter who must live in it for a while after I’m gone, I worry about the world. Because of her, I worry more than I otherwise might; on the other hand, because of her I also worry less. The old parental paradox: I see so many forces arrayed against her, but I also see her as a potent force for good.

I feel the same way about the family, in all of its diverse manifestations, though I worry about it much less. It too has forces arrayed against it, not the least of them economic, but none of those forces seem as formidable and firmly grounded as the family itself. That I believe families can be a force for good, I have already said. But even when they stand in the way of “the good,” retarding progress and diluting idealism, forever threatening to put a paunch on Che Guevara and a breast pump on Elizabeth Gurley Flynn, I find them virtuous. Visionaries who coax us to the “larger embrace” can sometimes squeeze us to death, and even if they don’t, you can bet their followers will. It is then that the family, with its shortsighted loyalties and pedestrian needs, acts as a brake on ideology’s merciless wheels. Before the Law and the Prophets, there were Adam and Eve.

The Family, by Egon Schiele, 1918. Österreichische Galerie Belvedere, Vienna, Austria.

Speaking of marriage in words that also apply to family, Supreme Court Justice William O. Douglas wrote that it “is an association that promotes a way of life, not causes; a harmony in living, not political faiths; a bilateral loyalty, not commercial or social projects”—including, one would like to add, the social project of a constitutional amendment defining marriage as “the union of a man and a woman.” Douglas was writing for the majority in Griswold v. Connecticut (1965), a landmark decision for reproductive freedom and privacy rights, but he was also speaking for the Botto family’s prerogative to tell their twenty thousand comrades when it was time to go home. It is almost as if Douglas sees the family as a kind of judiciary in human affairs, a tribunal that sits for life and from time to time declares itself constitutionally unable to abide this or that attempt to legislate happiness. The image of a nuclear family boisterously self-absorbed on an extremely cramped and crumby picnic blanket may not be anybody’s picture of a flying-carpet ride to paradise, but it is just about everybody’s best insurance against being dragged into utopia by the hair.

St. Paul makes his halfhearted case for the celibate life by remarking that husbands and wives are hampered in their religious devotion by caring more about pleasing each other than pleasing God, and I hope I am not being too perverse to wonder if it pleases God to have it that way—in the mass, or at least in the balance, so that even the most righteous projects will have their quotidian checks, so that one dogged gentile mother will not lack the wherewithal to bring the most famous of Jewish mothers’ sons almost to his knees with her incessant nagging, because she has a sick kid and she’s not going away without a cure, and don’t even bother to tell her about the other children with a prior claim, because this is the only child she cares about right now, the only one who breaks her heart. Isn’t that also a gospel?

Anyway, you can preach whatever gospel you like, write manifestos galore, teach queer theory in a cultural-studies course or found a neo-Shaker settlement in Maine, wax rhapsodic in defense of the patriarchal family or spit upon it with feminist contempt, there will still be that boy and girl sneaking away from the fold and returning nine months later with a bundle they can’t possibly manage on their own. It will take a whole village to raise that single child, though pity the child who has no more than a whole village to raise him, for whom there are no villagers willing to shoulder his upbringing as their particular job. Perhaps the job will fall to the fecund boy and girl; perhaps it will fall to their long-suffering parents, or to two women stealing away arm in arm on a road less traveled. Don’t be surprised if they too return “in a family way.” This is the second coming that is always coming, the ever holy and always peculiar family perpetually approaching on its ass. You can say you’re way past that sort of thing if you like, tell them there’s no room at the inn, but in the end—and if only by dying—you are going to make room.