Most new discoveries are suddenly-seen things that were always there.

—Susanne K. Langer, 1942Happy Accidents

Solving a problem like climbing a mountain.

I have been in a position to solve several mathematical physical problems, and some, indeed, on which the great mathematicians since the time of Euler had in vain occupied themselves; for example, questions as to vortex motion and the discontinuity of motion in liquids, the question as to the motion of sound at the open ends of organ pipes, etc.

But the pride that I might have felt about the final result in these cases was considerably lowered by my consciousness that I had only succeeded in solving such problems after many devious ways, by the gradually increasing generalization of favorable examples, and by a series of fortunate guesses. I had to compare myself with an Alpine climber who, not knowing the way, ascends slowly and with toil and is often compelled to retrace his steps because his progress is stopped; sometimes by reasoning, and sometimes by accident, he hits upon traces of a fresh path, which again leads him a little further; and finally, when he has reached the goal, he finds to his annoyance a royal road on which he might have ridden up if he had been clever enough to find the right starting point at the outset.

There are many people of narrow views who greatly admire themselves if once in a way they have had a happy idea, or believe they have had one. An investigator, or an artist, who is continually having a great number of happy ideas, is undoubtedly a privileged being and is recognized as a benefactor of humanity. But who can count or measure such mental flashes? Who can follow the hidden tracts by which conceptions are connected?

I must say that those regions in which we have not to rely on lucky accidents and ideas have always been most agreeable to me as fields of work. But as I have often been in the unpleasant position of having to wait for lucky ideas, I have had some experience as to when and where they came to me, which will perhaps be useful to others. They often steal into the line of thought without their importance being at first understood; then afterward some accidental circumstance shows how and under what conditions they have originated; they are present, otherwise, without our knowing whence they came. In other cases, they occur suddenly, without exertion, like an inspiration. As far as my experience goes, they never came at the desk or to a tired brain. I have always so turned my problem about in all directions that I could see in my mind its turns and complications, and run through them freely without writing them down. But to reach that stage was not usually possible without long preliminary work. Then, after the fatigue from this had passed away, an hour of perfect bodily repose and quiet comfort was necessary before the good ideas came. They often came actually in the morning on waking, as Gauss also has remarked: “The law of induction discovered Jan. 23, 1835, at seven AM, before rising.” But they were usually apt to come when comfortably ascending woody hills in sunny weather. The smallest quantity of alcoholic drink seemed to frighten them away.

Such moments of fruitful thought were indeed very delightful, but not so the reverse, when the redeeming ideas did not come. For weeks or months, I was gnawing at such a question. It was often a sharp attack of headache that released me from this strain and set me free for other interests.

Objet Trouvé #1, by Kiluanji Kia Henda, 2016. © Kiluanji Kia Henda, courtesy the artist and Galeria Filomena Soares, Lisbon.

My successes have had primarily this value for my own estimate of myself, that they furnished a standard of what I might further attempt; but they have not, I hope, led me to self-admiration. I have often enough seen how injurious an exaggerated sense of self-importance may be for a scholar, and hence I have always taken great care not to fall prey to this enemy. I well knew that a rigid self-criticism of my own work and my own capabilities was the protection and palladium against this fate. But it is only needful to keep the eyes open for what others can do, and what one cannot do oneself, to find there is no great danger; and as regards my own work, I do not think I have ever corrected the last proof of a memoir without finding in the course of twenty-four hours a few points that I could have done better or more carefully.

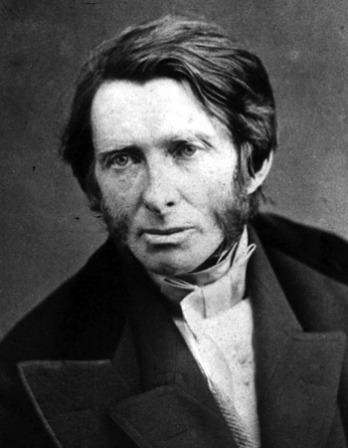

Hermann von Helmholtz

From “An Autobiographical Sketch.” From the 1850s to the 1890s, the Potsdam-born scientist presented epoch-making discoveries in thermodynamics, physiology, metabolism, optics, and electrodynamics. He delivered more than two dozen popular lectures in Germany, including this address, given on the occasion of his jubilee in 1891. “Whoever in the pursuit of science seeks after immediate practical utility,” he wrote in 1862, “may generally rest assured that he will seek in vain.” He died in 1894 in Berlin.