I think we are inexterminable, like flies and bedbugs.

—Robert Frost, 1959

Lonesome George, the last surviving Pinta giant tortoise, c. 2007.

In September 2014 I gathered at the American Museum of Natural History with scientists, journalists, and museum staff for the unveiling of the taxidermied body of Lonesome George, the last of the Pinta Island giant tortoises. I met George when he was an octogenarian and I was a twenty-year-old volunteer at the Charles Darwin Research Station in the Galápagos. I sometimes fed him leaves in his pen. Now, just a little more than a decade later, as the curators pulled away the cloth covering the display case, I felt queasy and sad. Most people clapped, probably because they didn’t know what else to do. George was standing up, legs and head outstretched, looking uncharacteristically energetic. The conversation quickly turned to the taxidermy job. One magazine reporter said her readers wanted “all the gory details.”

Lonesome George’s death in 2012 marked the end of a long struggle for existence by giant tortoises against humans who had hunted and eaten them, and who had introduced goats to their island, which destroyed their habitat. I searched the room and saw one person crying. It was biologist James Gibbs, who had been the one to courier George’s carcass to the museum. We spoke about the Galápagos and the event we had just witnessed. Gibbs said he wished the museum staff had told everyone about the time island fishermen took the tortoise hostage in a successful ploy to increase fishing quotas. I wished the museum staff had said something about how difficult it is to be a member of the species that bears the responsibility for the Pinta tortoise’s demise.

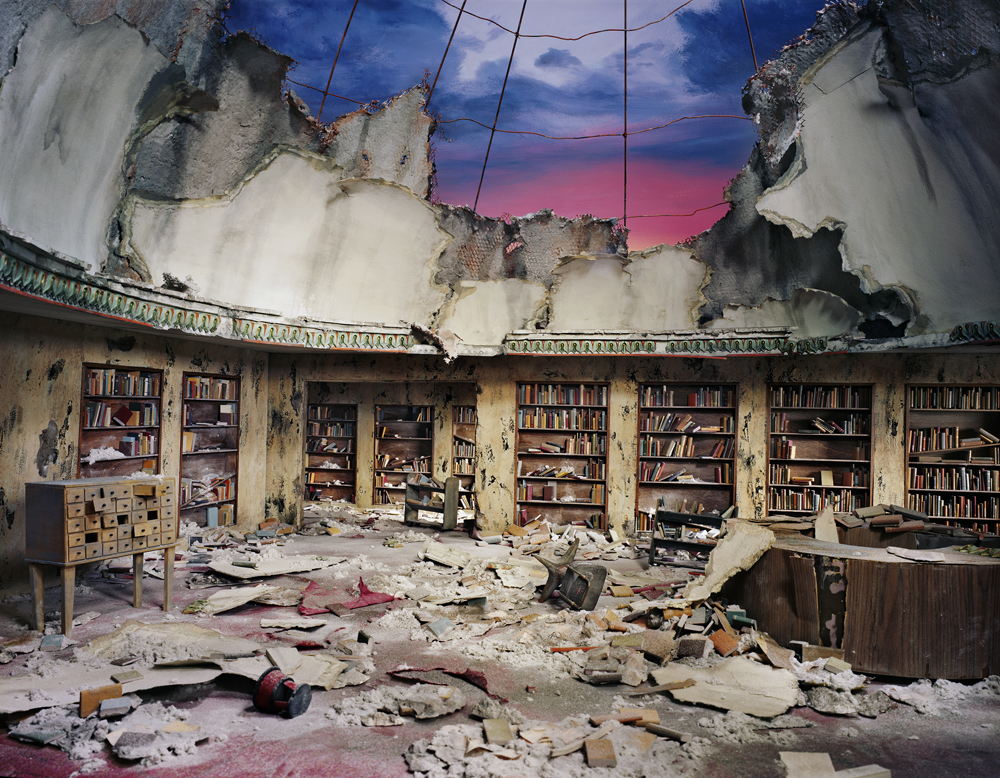

Circulation Desk, by Lori Nix, 2012. Archival pigment print, 30 x 40 inches. Courtesy the artist and Clamp Art Gallery, NYC.

When he was alive, Lonesome George was a captive reminder of biodiversity loss. One 2006 book called him “the only one of his kind left on earth—a symbol of the devastation man has wrought to the natural world in the Galápagos and beyond.” After his death, Washington Tapia, a researcher with the Ecuador National Park Service, told the New York Times it was like losing his grandparents. But even for people less intimate with him did his life and demise serve as a reminder of the mass extinction of species currently underway—the sixth in earth’s history but the only one caused by humans.

It was said more than once at the museum as well as in media coverage of his death that the tortoise had failed to reproduce. Placing blame on animals is part of the balm we apply to our uneasy consciences about extinction. In 1887 zoologist Leonhard Stejneger noted in an article on the Steller’s sea cow that “there is nothing surprising in the speedy extermination of this clumsy animal, which could not dive, and which had actually no means of defense or escape.” A 2014 Audubon article about Martha, the last passenger pigeon, which had died in the Cincinnati Zoo one hundred years earlier, noted, “Not once in her life had she laid a fertile egg.”

The question of infertility, however, is only a distraction from the sorrow of extinction. In 1947, when the Wisconsin Society for Ornithology erected a monument to the passenger pigeon, ecologist Aldo Leopold read a eulogy for the animal. “There will always be pigeons in books and in museums, but these are effigies and images, dead to all hardships and to all delights,” he said. “Book-pigeons cannot dive out of a cloud to make the deer run for cover, or clap their wings in thunderous applause of mast-laden woods. Book-pigeons cannot breakfast on new-mown wheat in Minnesota, and dine on blueberries in Canada. They know no urge of seasons; they feel no kiss of sun, no lash of wind and weather; they live forever by not living at all.”

Leopold also noted the existential crisis posed by extinction: the guilt extinction elicits is both contemporary and ours alone bear. “The Cro-Magnon who slew the last mammoth thought only of steaks,” he said. “The sailor who clubbed the last auk thought of nothing at all. But we, who have lost our pigeons, mourn the loss. Had the funeral been ours, the pigeons would hardly have mourned us.”

Leopold’s oration joined a litany of uneasiness about humanity’s impact on nature. In 1847 conservationist George Marsh noted in an address that climate was being “gradually changed and ameliorated or deteriorated by human action.” By 1864 Marsh had come to the conclusion that “of all organic beings, man alone is to be regarded as essentially a destructive power.” The idea that we were living in an era marked by humankind’s actions was common in the nineteenth century and continued into the twentieth. It picked up steam with a term first used in 1922 by Russian geologist Aleksei Pavlov and later in 2000 by atmospheric chemist Paul Crutzen: the Anthropocene.

There is no real doubt we are living in the human age. The unprecedented increases in the human population and earth-altering substances such as greenhouse-gas emissions, nitrogen runoff, and plastics are not the result of climatic shifts (like those that set the Holocene in motion roughly twelve thousand years ago) or because an asteroid hit the Yucatán (as it did 66 million years ago, putting an end to the Cretaceous Period and non-avian dinosaurs). The current major shocks to the planetary system are caused by human beings.

The more delusional among us see these changes as merely the latest in an ever-changing world, just a bigger cataclysm among earth’s many cataclysms. But that’s acceding to a temptation similar to that of the radar operator aboard the B-29 that delivered destruction to Hiroshima; he called the atomic bomb “just a bigger bomb.” Such incrementalism, pervasive and no doubt of some comfort, denies that the present moment requires a new conception of human responsibility. But humanity (or some faction of it) has become a uniquely powerful force on the planet. As a 2011 editorial in the journal Nature suggested, “The first step is to recognize, as the term Anthropocene invites us to do, that we are in the driver’s seat.”

The current array of species disappearances is comparable in rate and size to the five other mass extinctions in earth’s 4.5-billion-year history. But only since the second half of the twentieth century—with the creation of international scientific bodies, and databases that tally likely extinct species (to date, nine pages of very small font)—have we come to understand the magnitude. This havoc we have wreaked on earth’s biological system feels fundamentally different than that which we have wreaked on its physical system. We feel bad for warming glaciers and making the oceans more acidic, but we feel particularly bad about annihilating wild animals that managed to struggle for their survival alongside us year after year. They struggled against all odds but one.

Dealing with the disaster we have created means finding a way to reckon with our guilt for causing it. “Why stick around to see the last beautiful wild places getting ruined, and to hate my own species, and to feel that I, too, in my small way, was one of the guilty ruiners?” asked Jonathan Franzen in 2006. “The guilt of knowing what human beings have done” is how conservation biologist George Schaller described the feeling he gets when he looks at the Serengeti. In 2008 Schaller made one of the most definitive statements of Anthropocene-inspired self-reproach. “Obviously,” he said, “humans are evolution’s greatest mistake.” And in 2015 Pope Francis joined the chorus of mourners. “Because of us,” he wrote in his encyclical Laudato Si’, “thousands of species will no longer give glory to God by their very existence, nor convey their message to us. We have no such right.”

In 1961 psychoanalyst William Niederland coined the term survivor syndrome after conducting a study of those who survived Nazi concentration camps as well as survivors of natural disasters and car accidents. Niederland noted that among their symptoms were chronic depression and anxiety. Many camp survivors whom the SS had “selected” to live found it difficult to relate to ordinary people and have ordinary feelings. Sigmund Freud had intimated the idea in an 1896 letter in which he discussed his father’s death, describing a “tendency toward self-reproach which death invariably leaves.” Niederland’s findings gave a name to a condition that also afflicted some survivors of the Titanic: of the 705 people who survived the ship’s sinking, during which more than 1,500 passengers and crew died, at least ten went on to commit suicide. That’s a rate more than a hundred times higher than the current U.S. suicide rate. Frederick Fleet, the Titanic lookout who first spotted the iceberg that sank the ship, was the last. He hanged himself only a few years after Niederland published his study.

Once you hear the details of a victory it is hard to distinguish it from a defeat.

—Jean-Paul Sartre, 1951The psychiatrist Arnold Modell expanded the concept of survivor guilt to include less traumatic events, including the guilt some feel when they believe they are better off than others in their family. He pointed to “an unconscious bookkeeping system” operating in mental life. When “other members of the family do not survive,” he wrote in 1983, “those who achieve upward mobility may do so at the expense of the guilt of leaving other family members behind.” Modell suggested that survivor guilt was not an affliction reserved for trauma victims who happened to have survived. People who could be considered agents of destruction also experience it.

One such agent was Claude Eatherly, among the forty-two U.S. Army men directly involved in dropping the atomic bombs on Japan. He had flown over Hiroshima and given the signal. Alone among the forty-two, Eatherly rejected a hero’s treatment after his return and instead expressed profound guilt for what he had done. His guilt was off-message, however, and for this and other reasons his reputation was called into question. In 1959 he offered his interpretation. “The truth,” he wrote, “is that society simply cannot accept the fact of my guilt without at the same time recognizing its own far deeper guilt.”

Eatherly’s view anticipated an even broader expansion of guilt by some psychologists, one in which survivor and collective guilt bleed together. This collective form of survivor guilt could be felt throughout a group as the result of perpetrating harm, even if no individual in the group directly contributed to the harm. Examples of this may be construed in the less typical but persistent guilt some feel today about slavery, war, genocide, or white privilege.

Survivor guilt may also exist at the species level. That humans have helped bring on other species’ end times is not an easy feeling to deal with. Survivor guilt in the Anthropocene may describe how we respond to harm done by humankind’s ever-increasing dominance. Given that we bear responsibility for balancing the interests of human and nonhuman life, it’s no surprise that some among us feel we are not doing a satisfactory job.

Guilt, of course, can be debilitating and self-destructive. But philosophers and psychologists have argued it can also motivate people to make reparations for their transgressions—as seemingly was the case with Claude Eatherly, who sought in his own way to prevent the dropping of future atomic bombs. In a 2013 study German university students read an article about how Germany was responsible for harming the climate. Respondents who reported feeling more intense guilt also expressed greater intention to repair the damage.

A complication of survivor guilt in the Anthropocene is that the disaster continues; our guilt is concurrent with it. It’s also anticipatory: the burden of guilt applies not only to what we have done but what is yet to come—and what it will mean for our own species’ survival. Scientific models can predict how warm the planet will get, what percentage of corals will die, how acidic the oceans will become, how many more species will vanish in the near future. As a result, we are able to question what our future holds. We are now making a decision “on the unconsulted behalf of perhaps 100 trillion of our descendants,” wrote British environmentalist Norman Myers, “asserting that future generations”—at least 200,000 of them, lasting twenty times longer than humans have so far been around—“can certainly manage with far less than a full planetary stock of species.”

Research into collective guilt has focused mostly on harms committed in the past, but some researchers are now concentrating on the future. For a study published in 2012, nonaboriginal Canadian college students read fictional newspaper articles about a dam project. In one, the project had flooded thousands of acres of aboriginal lands a month prior. In the other, the project would flood thousands of acres a month in the future. Compared to harm in the past, harm in the future induced significantly more guilt.

What sort of amends could we expect survivor guilt at the species level to produce? Some people are now trying to protect land and sea from human impact. Others eliminate invasive species that humans ruinously introduced into native habitats, like the goats on Lonesome George’s island of Pinta. There are breeding programs for endangered species in captivity; such a plan resurrected the population of black-footed ferrets in the western Great Plains. Armed bodyguards protect the world’s last male northern white rhino in Kenya. And some are relocating species whose habitats we have encroached on in one way or another, a process known as “assisted colonization.”

The idea that has garnered the most attention recently is the revival of species, or de-extinction. This is how James Gibbs, courier of Lonesome George’s body, appears to be coping with the tortoise’s death. He is working to breed tortoises that contain hybrid DNA from Pinta tortoises. If successful, this will eventually produce an animal genetically similar to the original. “You can become paralyzed by extinction,” Gibbs has said about the project, “or you can get to work.”

The website of Revive & Restore, one of the leading groups advocating for de-extinction, calls the task “the greatest undertaking conservation science has ever attempted” while also claiming it is “simple in principle.” Some de-extinction attempts, however, reveal the vast complexity of the enterprise. In early 2015 geneticist George Church and his colleagues inserted fourteen woolly mammoth genes into lab-grown elephant cells, an early step toward reviving the extinct creature. But among the factors that scientists have noted put terrestrial vertebrates at risk of disappearing in the Anthropocene are: a small geographic range (the mammoth’s habitat continually shrinks as the tundra warms), low reproductive rates (the mammoth is not a fast breeder), and large body size (repeat: mammoth). Revive & Restore’s list of criteria for deciding the best candidates for “genetic rescue” includes that the original causes of extinction have been resolved and that new threats can be managed. Regarding the woolly mammoth, the organization can answer only with maybes.

I would love to know woolly mammoths were lumbering across Siberia again. But some proponents of de-extinction act as if existence is the only problem these species face. De-extinction alone does not address the causes of extinction, the condition of habitats, or the quality of species’ lives. We cannot refreeze the Arctic tundra, former home of the woolly mammoth, nor can we postpone the arrival of spring, which climate change impels to come earlier every year. We cannot resurrect the cold snap that once prevented the mountain pine beetle from destroying northern forests. There is no satisfactory way to wipe the record clean.

Built as it is from the Greek anthropos, the term Anthropocene implicates all of humanity. This could be a dangerous way of seeing ourselves. Studies of the placebo effect have long shown that if we believe an inert pill to be real, some will experience suggested benefits. But there is also the so-called nocebo effect, in which some will experience suggested negative side effects of a placebo. Naming the Anthropocene might work the same way, bringing to bear an alarming fait accompli: human destruction could be exacerbated if we believe that destruction is what we do—that environmental destruction is a byproduct of human nature. Call it the anthropocebo effect.

The Destruction of the House of Job and the Theft of His Herd by the Sabians, by Bartolo di Fredi, 1536. © Collegiata, San Gimignano / Bridgeman Images.

Belief in determinism can be a powerful force in guiding behavior. In one study, students who read a text that explained how free will is an illusion because genetics and environment determine behavior cheated to a significantly greater degree in a follow-up experiment than students who read a text that stated a contrary view. Similarly, framing the Anthropocene in a deterministic way may lead us to accept humans as an inevitably destructive geologic force. A sense of inescapable complicity could lead us to forget that humans are capable of acting differently.

History further complicates the term. Many argue that casting the whole species together in such a way is imprecise because only some humans—specific societies coupled with certain economic systems and technologies—are to blame. In this context, the Anthropocene’s start date may be taken as an indicator of who is responsible—and therefore who might be obligated to act. Proposed dates have included the beginning of farming eleven thousand years ago or its rise eight thousand years ago; the year 1500 (based on an opaque calculation involving human population, affluence, and available technologies); the year 1610 (when an exchange of species between the Old and New World caused a drop in human population and farming, leading to a regeneration of forests and a concurrent decline in atmospheric carbon dioxide); the Industrial Revolution of the late eighteenth century; a period after World War II known as the Great Acceleration; and various years related to the detonation of nuclear weapons, including 1945, 1952, and 1964.

Of this list, nuclear-weapons testing stands out. While radioactive fallout did not fundamentally change the functioning of the earth’s biological system, it did leave a well-defined signature in the geologic record. The date is also compelling for social reasons: nuclear technology left a ready marker in the stratification of our collective psyche—it was the moment we realized we were a hazard to ourselves.

The Anthropocene may also help us acknowledge our sense of what we’ve done and what we still might do. The term’s official adoption into the geological timescale could take place this fall when it comes to vote at the International Geographical Congress. But the vote itself is largely academic: our geological moment is here. As with nuclear weapons, its most interesting questions relate not to what to build or resurrect but to what we can undo and prevent. Survivor guilt in the Anthropocene could be put to good use if we view our social identity as malleable rather than fixed and can recognize that humans are in the driver’s seat before the coming planetary wreck. It might be our chance to believe we can steer away from ultimate disaster—that we have not simply been a great evolutionary mistake.