Imagination continually outruns the creature it inhabits.

—Katherine Anne Porter, 1949The Person in the Ape

A history of humans trying and failing to understand the minds of apes.

By Ferris Jabr

Rôle de Joko, by Charles Mazurier, c. 1826. The New York Public Library, Jerome Robbins Dance Division.

Audio brought to you by Curio, a Lapham’s Quarterly partner

Around 500 bc, the Carthaginian explorer Hanno the Navigator guided a fleet of sixty oared ships through the Strait of Gibraltar and along the northwest lobe of the great elephant ear that is the African continent. Toward the end of his journey, on an island in a lagoon, he encountered a “rude description of people”—rough-skinned, hairy, violent. The local interpreters called them Gorillae. Hanno and his crew attempted to capture some of them, but many climbed up steep elevations and hurled stones in defense. Eventually, the Carthaginians caught three female Gorillae, flayed them, and brought their skins back home, where they hung in the Temple of Tanit for several centuries.

Though scholars dispute whether the Gorillae were gorillas, chimpanzees, or an indigenous tribe of humans, many regard Hanno’s account as the oldest surviving record of humans encountering another species of great ape. The ambiguity of Hanno’s early descriptions—are the Gorillae human or beast, people or apes?—is not just an artifact of translational difficulties; it is exemplary of a profound misunderstanding in historical attitudes about our closest animal cousins, a confusion that is still being resolved today.

On a windy spring morning two years ago, at an ape sanctuary and research facility in the heart of North America, I had an encounter of my own. Spread over six acres of forest, fields, and lakes in Des Moines, Iowa, the Ape Cognition and Conservation Initiative is home to a clan of five bonobos, including the renowned Kanzi, perhaps the most linguistically talented ape ever studied. When Kanzi was an infant, researchers tried to teach his adoptive mother to communicate using an array of lexigrams on a keyboard. She never made much progress, but Kanzi, like a human child exposed to language, began to use the symbols on his own. Today, he knows the meanings of hundreds of lexigrams and understands many phrases of spoken English as well.

Inside the research facility, I approached a glass panel separating an experiment chamber from a hallway. Kanzi rushed forth, slapping and pounding the glass—a typical greeting for a stranger. Initially, he was more interested in playing—lolling around in blankets, drizzling himself with cool water—than demonstrating his vocabulary. But one of the researchers eventually coaxed him onto a platform in front of a large touch screen. With the perfunctory tone of a teacher giving a spelling test, a computerized voice spoke one word at a time: bug, fish, tickle. The screen simultaneously presented a selection of colorful symbols, which looked like hobo signs contrived by Matisse. Kanzi’s goal was to press the symbol that corresponded to the spoken word. He got the first few wrong. “Kanzi, you got to listen, bud!” said Jared Taglialatela, one of the research directors. “Sometimes we can tell when he’s not really paying attention.”

“Balloon!” the computer said. Kanzi pressed a red symbol that looked like an umbrella missing its handle. Two triumphant tones followed. “Gorilla!” Kanzi pressed on a yellow circle with a long, curling tail. Correct. “Cereal.” Right again.

It was not until the late twentieth century that we began to recognize just how clever, empathic, and self-aware apes really are. Pioneering primatologists Jane Goodall, Dian Fossey, and Biruté Galdikas conducted long-term field studies of wild chimpanzees, gorillas, and orangutans respectively, documenting their previously unknown talent for toolmaking, their individual personalities, and the intricacy of their relationships. David Attenborough astounded and delighted the world by canoodling on camera with a family of gentle mountain gorillas. Francine Patterson taught sign language to Koko the gorilla. In decades of intensive, sometimes misguided studies, researchers schooled and quizzed captive apes, diapered and civilized them, and made them live alongside humans in human households. Controlled experiments tested to what extent great apes could match our own intellectual abilities: whether they could solve complex problems, cooperate to achieve a common goal, and intentionally deceive others.

Diana and Endymion, etching by Frank Short after George Frederic Watts, 1891. © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, The Elisha Whittelsey Collection, the Elisha Whittelsey Fund, 1959.

The story of people and apes is a story of intimacy, estrangement, betrayal, and attempted reconciliation. It stretches from long before Hanno’s explorations to the inception of modern primatology to the present day. In that time, we have made much progress in understanding our ape cousins—in seeing them, and ourselves, more clearly. We now know that all the great apes—chimpanzees, bonobos, gorillas, orangutans, and ourselves—are extremely similar in both body and mind; that we share a great deal of genetics, evolutionary history, and cognition; that we all have thoughts, emotions, dreams, and a conscious experience of the world. We know that apes remember past events in detail and plan for the future; they are masters of mimicry, learning to use human tools simply by observing; they can understand spoken language and communicate with gestures and abstract symbols; they methodically cooperate to hunt and defend their territory; they maintain unique cultures, passing down particular toolmaking techniques, dialects, and habitat-specific survival skills from one generation to the next; they form lifelong kinships, mourn their dead, and are just as dependent on social intimacy as we are; they can recognize their reflections and have a sense of self. They are, in sum, highly intelligent, self-aware, autonomous individuals.

But the more we accept the deep similarities between humans and other apes, the more pressing it becomes to address the unresolved tension in the sinews of our relationship: whether we need to change our definition of a human—or, more profoundly, what it means to be a person.

Thirty million years ago, humans and the other great apes did not exist. Instead, numerous tree-vaulting primates lived in Africa and Asia. Over time our primate predecessors continued to speciate, adapting to distinct habitats and ecological roles. Some shrank and embraced life in the treetops; others became increasingly large, favoring the ground, or swinging fluidly between forest floor and canopy. Between six million and eight million years ago, humans split from their last common ancestor with chimpanzees. Even after they were established as distinct species, early humans and other great apes undoubtedly crossed paths—by accident and in conflict—for hundreds of thousands, if not millions of years. In Vietnam paleontologists have uncovered mingled human and orangutan bones dated to half a million years ago.

Whereas the other great apes remained in relatively restricted habitats, humans colonized the globe. We migrated out of the jungle and savannah, building farms and cities, surrounding ourselves with domesticated grasses and lumbering cattle. Firsthand knowledge of other apes was largely forgotten. From the time of Hanno until the eighteenth century, the majority of the world regarded the existence of apes as more myth and rumor than fact. The West heard tales of hirsute humanoids—satyrs or pygmies, they were often called—roaming the forests of Africa and Asia. They were sometimes depicted as savages, bloodthirsty and lustful, sometimes more like elusive wood nymphs. Some people thought they were the unnatural offspring of clandestine trysts between human women and monkeys.

The sleep of reason produces monsters.

—Francisco Goya, 1799In 1591, Italian explorer Filippo Pigafetta published a somewhat credible account of apes in the wild. A Report of the Kingdom of Congo, based on the tales of Portuguese sailor Eduardo Lopez, describes “multitudes of apes” on the banks of the Congo River that “afford great delight to the nobles by imitating human gestures.” At the time, ape referred to any number of primates, including baboons, macaques, and other monkeys, but the book contains an engraving of two tailless creatures that look very much like chimpanzees. In the 1600s, English clergyman Samuel Purchas related the memories of English soldier Andrew Battel, who was captured by the Portuguese in the 1590s and held captive in equatorial Africa for two decades. He gives a vivid description of wordless, hollow-eyed, dun-haired creatures called Pongos, proportioned like humans but much larger, who were known to gather around fading campfires and to cover their dead with branches—an early reference to gorillas.

It was not until the mid-seventeenth century, when explorers started to bring apes back to Europe—stuffed into cages on ships or preserved in barrels of liquor—that naturalists began to acknowledge chimpanzees, gorillas, and orangutans as flesh-and-blood organisms. Nicolaes Tulp, a Dutch physician and professor of anatomy, repeatedly visited the menagerie of Frederick Henry, Prince of Orange, to study what he variously called an Indian satyr and an ourang outang, an Indonesian phrase meaning “person of the forest.” In his 1641 book Observationes Medicae, Tulp described the startling finesse with which the young ape drank water from a jug and covered herself with a blanket when going to sleep. The creature Tulp observed was most likely a chimpanzee, but the phrase ourang outang stuck and became a popular moniker for apes of all kinds.

In 1699 the Royal Society of London released a landmark publication in the history of primatology, British physician Edward Tyson’s thorough treatise on chimpanzee anatomy. He noted in particular that the chimp’s larynx and brain were extremely similar to those of a human, but he was firm in his conviction that the specimen was simply another animal, not a kind of human or a mythological creature. It was a “brute animal sui generis,” he wrote, “a particular species of ape.” Although it was capable of speech, given the structure of its voice box, he believed it remained mute because it lacked “those nobler faculties in the mind of man.”

Despite these early attempts at scientific portraits of the so-called pygmy and satyr, the eighteenth century was a time of bewilderment and contradiction regarding the nature of apes, whose physical existence could no longer be denied. In contrast to Tyson, many people thought humans and apes could not be so neatly separated or catalogued. The ape became a kind of fun-house mirror of humanity, reflecting by turns childlike innocence and terrifying beastliness. In the early 1700s, a traveler named Jan Velten visited a menagerie attached to an inn in Amsterdam and sketched the animals there, including an ape. He depicts her as an ugly, upright, hairy anthropoid with a lion’s mane, Klingon’s nose, and long, witchlike fingers. As late as 1790, a list of attractions in London styled various apes on display as Wood Monster, Satyr of the Woods, Man-Tyger, Arabian Savage, and Little Black Man.

Approaching Thunder Storm (detail), by Martin Johnson Heade, 1859. © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Erving Wolf Foundation and Mr. and Mrs. Erving Wolf, in memory of Diane R. Wolf, 1975.

The lingering concept of the ape as a brute or monstrous chimera contrasted sharply with an emerging picture of apes as sentient, intelligent, even sensitive beings. In A Voyage to and from the Island of Borneo, published in 1718, Daniel Beeckman describes a young orangutan with a toddler’s temperament and a penchant for alcohol:

If our backs were turned, he would be at the punch bowl, and very often would open the brandy case, take out a bottle, drink plentifully, and put it very carefully into its place again…If at any time I was angry with him, he would sigh, sob, and cry till he found that I was reconciled to him.

In 1776, after many letters to his contacts in the Dutch East Indies, naturalist Arnout Vosmaer finally acquired a live female orangutan for William V, Prince of Orange. At first Vosmaer kept the orangutan in his house, but when the number of curious visitors became overwhelming, he transferred her to the prince’s menagerie, shackling her to an enclosure with a leather collar and iron chain. She loved bread, carrots, peas, strawberries, parsley, and sweet Malaga wine. She wielded forks and spoons with surprising grace, used toothpicks, and wiped her lips with a napkin. She hated to be left alone and often clung to people, especially a servant tasked with her care. Each night she made her bed, spreading flat some linens and tucking herself in. She once tried to open the door of her enclosure with a piece of wood, having seen someone use a key. Prince William wrote that she showed “a more than animal intelligence.”

Around the same time, Scottish judge James Burnett, Lord Monboddo, published an astonishing document in which he argued the ape was

an animal of the human form, inside as well as outside…That he has the sentiments and affections common to our species…and likewise an attachment of love and friendship…That they live in society and have some arts of life; for they built huts and use an artificial weapon for attack and defense, viz., a stick; which no animal merely brute is known to do…They appear likewise to have some civility among them, and to practice certain rites, such as that of burying the dead.

Similarly, in his 1755 Discourse on the Origin of Inequality, Jean-Jacques Rousseau wrote that “we find in the descriptions of these supposed monsters striking similarities to the human species and fewer differences from men than these one could find between one man and another.” Apes were different from monkeys, Rousseau argued, because, like humans, they could learn and adapt.

Your mind’s got to eat, too.

—Dambudzo Marechera, 1978When Carl Linnaeus published the first edition of Systema Naturae, in 1735, he classified humans and apes in different genera—the former in Homo and the latter in Simia—though he put both within the class Anthropomorpha. By the tenth edition, in 1758, he included both Homo sapiens and Homo sylvestris orang-outang under the Homo genus. For a time, apes were officially classified as a kind of human. In 1809, French naturalist Jean-Baptiste Lamarck went so far as to suggest that, through a process of “transmutation,” knuckle-walking apes had turned into humans—that the great apes were the direct ancestors of people.

Many other naturalists vehemently disagreed, in particular Georges-Louis Leclerc de Buffon, who maintained that God had created a hierarchy of discrete species with humans at the summit. He stressed that apes could not speak and that they almost never walked upright. Even if their anatomy was similar to humans, they were not capable of using it in the same way because they were not “animated by a superior principle.” Apes were mere matter; humans had souls.

It would be more than a century before an English naturalist challenged the very word of God and the Western scientific community began to change its mind.

On a chilly, cloudy day in March 1838, Charles Darwin, back home from his five-year journey on the Beagle, visited the London Zoological Gardens, where he spent some time observing an orangutan named Jenny. When a keeper denied Jenny an apple, he later wrote, she threw herself on her back and began to bawl. The keeper promised to give her the apple if she behaved herself. Seeming to understand his meaning perfectly, she composed herself with great effort and accepted her reward.

Darwin returned several times that year to study apes acquired by the zoo. They were nervous around dogs but congenial with cats; they loved to play with sticks and hay; and they used handkerchiefs like shawls. They were especially curious about mirrors, making faces at their reflections, puckering their lips, and inspecting the glass from every angle. “Let man visit ourang-outang in domestication,” Darwin wrote,

hear [its] expressive whine, see its intelligence when spoken [to], as if it understood every word said—see its affection to those it knows—see its passion and rage, sulkiness and very extreme of despair; let him look at the savage, roasting his parent, naked, artless, not improving, yet improvable, and then let him dare to boast of his proud preeminence.

The publication of Darwin’s On the Origin of Species in 1859 and The Descent of Man in 1871, along with works by his contemporaries Alfred Russel Wallace, Charles Lyell, and Thomas Huxley, ignited a new era of scientific debate. The idea that the world’s extant creatures had not always existed—that the history of life on Earth was a succession of extinctions and rejuvenations, that organisms gradually changed form and split into distinct species—had been germinating for a while. But it was now more clearly, boldly, and fully articulated than ever before. An 1871 essay in the Edinburgh Review captures the spirit of the time:

Since the publication of the Origin of Species in 1859, no book of science has excited a keener interest than Mr. Darwin’s new work on the Descent of Man. In the drawing room it is competing with the last new novel, and in the study it is troubling alike the man of science, the moralist, and the theologian. On every side it is raising a storm of mingled wrath, wonder, and admiration.

Of all the startling implications, the most difficult for many people to accept was the notion that apes and humans were not just superficially similar but intimately related—that they shared an evolutionary history. The ape itself became a central symbol of the controversy. Numerous cartoons lampooned Darwin as a decrepit or clownish primate. Although some scholars conceded that Darwin was surely right about the similarities of human and ape anatomy, few believed humans had inherited their intellectual talents from primates or any other animals. The protests of Buffon continued to echo. Surely the human mind was too unique, too refined, to have descended from beasts.

In the following decades, witnessing a slew of fossil discoveries and newly published natural histories, most scientists in Europe and America accepted the core tenets of Darwin’s evolutionary theory, though the primary mechanisms of evolution were still hotly contested. Humans were officially recognized as one of the great apes, and, eventually, all great ape species were nestled on a cluster of branches in the great tree of life.

my mind is

a big hunk of irrevocable nothing

It was the first major reconciliation between people and apes, though a relatively superficial one. And by officially linking humans and apes in a shared lineage, Darwin simultaneously created a new gulf between the two. In the past the apparent psychological similarity of people and “ourang-outangs,” combined with the mystery of their origins, had fomented the idea that apes were a kind of human. Now that apes were known to be distinct species from humans—now that science had overwritten the long-standing mythology of apes and resolved their humanoid ambiguity—there was a new burden of proof on those who claimed the inner lives of people and apes were similar or equal. It was difficult to deny the skeletons and anatomical diagrams, but consciousness was far more intangible. Even if humans and apes were biologically related, even if they had inherited homologous forms, did they really have the same kind of mind?

We are still asking ourselves iterations of that same question. Before the 1800s apes drifted through a conceptual purgatory, sidling along the borders of myth, beast, and human. In the nineteenth century, by the authority of science, they assumed a new identity as biological animals. Now, with the magnitude of their sentience and intelligence fully established, they are poised to transition again—from animal to person.

Under modern U.S. law, a person is not necessarily the same thing as a human being. All members of Homo sapiens—whether they are infants, comatose, or highly competent adults—are “natural persons” who merit a suite of rights protecting their well-being and freedom simply by virtue of being human. In contrast, a “legal person” is entitled to a narrower set of rights but need not be human. Throughout history all kinds of nonhuman entities have been defined as legal persons: corporations, books, rivers, ships, and states. Yet in the United States and the majority of countries around the world, this term has never been extended to any nonhuman animal. Members of all species apart from our own are typically regarded as property—as things.

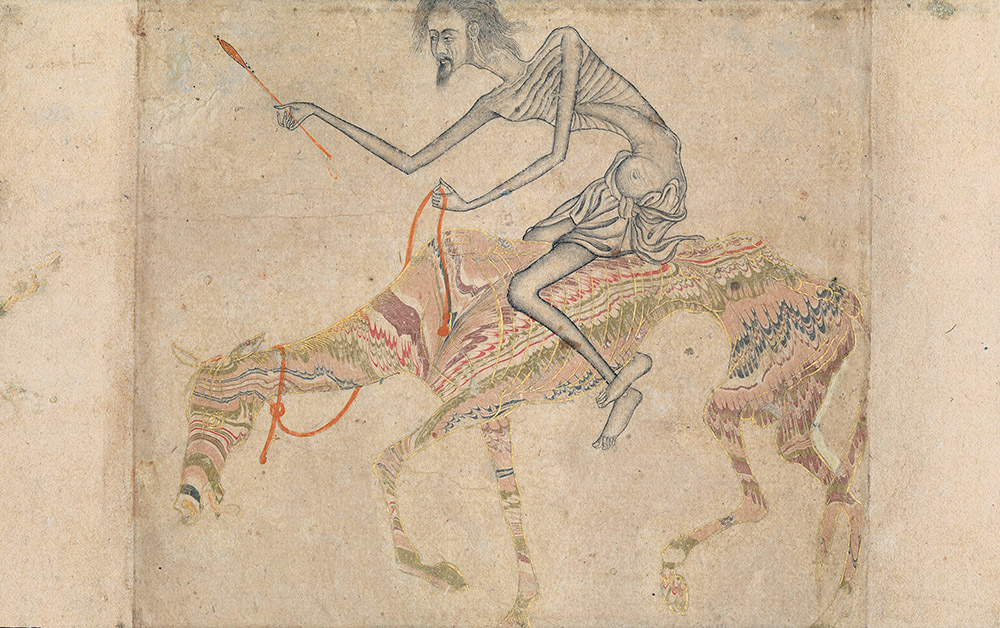

Emaciated Horse and Rider, India, c. 1625. © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund, 1944. Symbols of bodily desire in Sufi imagery, horses are often shown starved and beaten.

A subset of lawyers, philosophers, and scientists think this position is indefensible. If an inanimate object can be a legal person, surely some of the planet’s most intelligent animals can, too. Legal personhood would protect certain animals from abuse, imprisonment, and murder. As early as 1993, in a book called The Great Ape Project, collectively authored by more than thirty scholars, scientists, and philosophers, legal scholar Gary Francione argued that “any classification of person that excludes some great apes entirely from the sphere of personhood is, based on the clear and indisputable mental and emotional similarity among all great apes, thoroughly irrational.” Today the leader of the ape-personhood movement is an American lawyer named Steven Wise, founder and president of the Nonhuman Rights Project, which advocates legal personhood for great apes, dolphins, elephants, and whales.

“It should now be obvious that the ancient Great Wall that has for so long divided humans from every other animal is biased, irrational, unfair, and unjust,” Wise wrote in his 2000 book Rattling the Cage.

It is time to knock it down. The decision to extend common-law personhood…will arise from a great common-law case. Great common-law cases are produced when great common-law judges radically restructure existing precedent in ways that reaffirm bedrock principles and policies. All the tools for deciding such a case exist. They await a great common-law judge…to take them up and set to work.

Looming beneath the legalities is a more profound philosophical question with urgent moral implications: What does it really mean to be a person? Bolstered by the evidence of modern evolutionary science, of twenty-first century anthropology, genetics, and neuroscience, we can confidently declare that apes and humans are discrete but related species, that they share common ancestors, that they, quite literally, come from the same place. We can rattle off precise Linnaean terminology and even recite long stretches of DNA identical in all species. But none of that addresses what we mean by the word person. In some ways we are less enlightened, less clear-eyed now than we were four centuries ago. Our increasing scientific precision has so neatly partitioned ape from human that, in many people’s minds, human and person have all but fused.

Though this be madness, yet there is method in’t.

—William Shakespeare, 1603Once, in New York City, I attended a kind of salon with other writers and scientists, where I discussed animal sentience and growing support for ape personhood. “But it’s just a legal loophole,” someone protested. “Apes aren’t humans.” No, they’re not, I responded. But they are people. There’s a difference. “I don’t think there is,” said the protester. I held my tongue then, but what I should have said was that there absolutely is a difference—not just legally but ontologically. That’s the cognitive leap the evidence begs us to make. Person and human are not synonyms. Humans are a type of person, just one of many types of people on the planet—likely far more than we realize. Ultimately, personhood is not defined by taxonomy or anatomy or genetics. When we strip everything else away, when we ask ourselves what the essence of personhood is, what it means to be an individual, we arrive at one thing: consciousness, a subjective experience of the world, a mind at work. How, then, can we deny that apes are people, too?

Twenty years ago a chimpanzee named Cecilia was born in Argentina’s Mendoza Zoological Park, the same zoo that eventually became infamous for its deplorable conditions and the plight of Arturo, known as the “world’s saddest polar bear,” who died in July 2016. Like many animals at the zoo, Cecilia spent her days in a desolate pen, a twenty-square-meter cage of concrete and metal fencing with little natural light. One photo shows Cecilia curled in a semifetal position on a concrete ledge that appears to be spray-painted with the weak semblance of jungle vines. For a while at least, Cecilia was not alone, but her companions, Charly and Xuxa, both died unexpectedly in 2014 six months apart. Then in 2015 the Association of Lawyers and Professionals for Animal Rights petitioned Argentina’s courts to grant Cecilia a writ of habeas corpus (a formal investigation into the validity of an individual’s imprisonment), declare her a legal person, and order her transfer to a sanctuary.

Hypnotist and his patients, c. 1845. Photograph by John Adams Whipple. © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gilman Collection, Gift of The Howard Gilman Foundation, 2005.

In November 2016, Argentine judge María Alejandra Mauricio passed down a ruling. She decreed that Cecilia was a “nonhuman legal person” with “inherent rights”—the first legal decision of its kind in history. “This is not about granting them the same rights humans have,” she wrote,

it is about accepting and understanding once and for all that they are living, sentient beings with legal personhood and…the fundamental right to be born, to live, grow, and die in the proper environment for their species…I consider that the habeas corpus action is the applicable procedure, adjusting the interpretation and decision to the specific situation of an animal deprived of [her] essential rights.

On April 5, 2017, Cecilia arrived at her new home, a large sanctuary in Sorocaba, Brazil, which houses about fifty other apes. It was the first time she had ever set foot on grass. Initially, she was fearful. “She’s still very distrustful,” the sanctuary’s owner told local media that month. “She’s still really afraid of returning to the hell where she was living. When she hears an engine or some truck, she hides because she thinks they’re going to take her back.”

Gradually, she became more confident. In late August the sanctuary introduced Cecilia to a young male chimpanzee, Marcelino, whom she had been eyeing through a window in her enclosure. At their first meeting, he rampaged through Cecilia’s home. She fled, shrieking. After an hour’s separation, the two reconciled. Cecilia groomed Marcelino intensely. They embraced and kissed. They have rarely been apart since. Though they have plenty of open space to roam, they often choose to stay in catwalks and tunnels, away from the eyes of humans who have so thoroughly misunderstood them, ignored or diminished the evidence of their sentience, and denied their personhood—whose best attempt at emancipation has been to provide a larger prison.