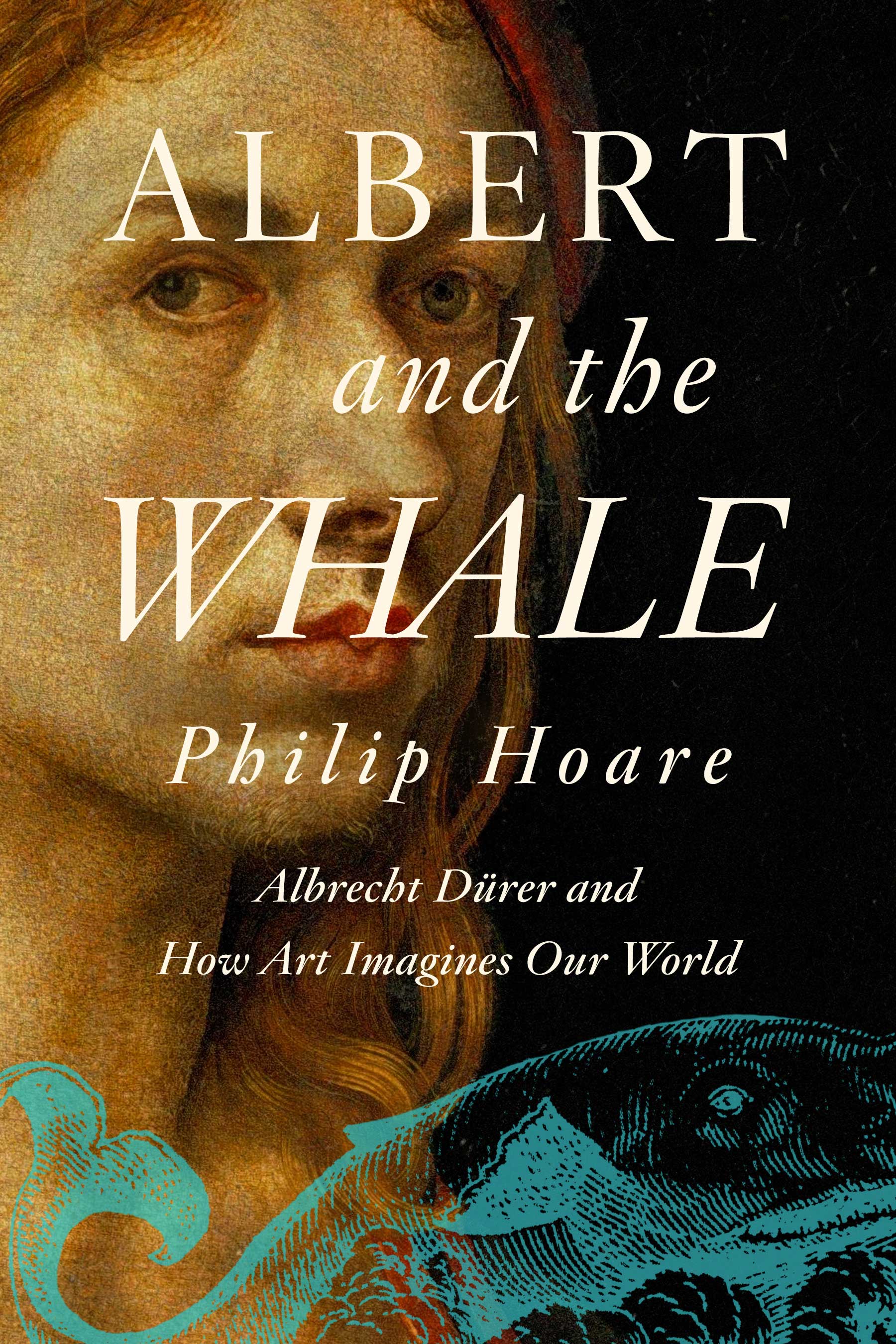

Back of Saint Jerome, by Albrecht Dürer, c. 1496. National Gallery, London.

“Hidden round the back of Albrecht Dürer’s St. Jerome of 1494, one of his first paintings…is this enormous star,” Philip Hoare writes in Albert and the Whale: Albrecht Dürer and How Art Imagines Our World. “You would have seen it only if you knew its secret: the galactic event going on, on the other side. Radiating orange-red rays, careering through the perpetual night. A thing of darkness created in light.” Why did Dürer paint it? “On the night of November 7, 1492, a large meteorite fell to earth outside the village of Ensisheim, accompanied by crashing thunder and lightning as it hurtled through the clouds. It was visible and audible 150 kilometers away. Only one witness, a young boy, saw it actually plunge into the field; but Dürer, abed nearby in Basel that night, could certainly have heard it…I don’t know if Dürer visited it, but his emperor Maximilian did; he declared it a wonder of God and chipped off a piece for himself. The meteorite might have been the rock with which Jerome beat himself, or an emblem of the New World. But more than anything, it was a sign of Dürer’s genius, as if that little panel he had painted was an announcement of his explosive talent.”

In this episode of The World in Time, Lewis H. Lapham and Philip Hoare discuss Dürer’s brilliance, what his art meant to people throughout history, and the centuries-long ubiquity of his woodcut of a rhinoceros—an animal the artist had never seen.

Lewis H. Lapham speaks with Philip Hoare, author of Albert and the Whale: Albrecht Dürer and How Art Imagines Our World.

Thanks to our generous donors. Lead support for this podcast has been provided by Elizabeth “Lisette” Prince. Additional support was provided by James J. “Jimmy” Coleman Jr.