A tree’s a tree. How many more do you need to look at?

—Ronald Reagan, 1965Messages in a Bottle

Nature is the only artist, the wonder of her collected works formed by their reflections in the mirrors of the human imagination.

By Lewis H. Lapham

Birds and Flowers of Spring and Summer, by Kano Eino, late seventeenth century. Suntory Museum of Art, Tokyo, Japan.

To me the converging objects of the universe perpetually flow,

All are written to me, and I must get what the writing means.

—Walt Whitman

To read the newspapers these days is to know whereof the poet spoke. Whitman had in mind the writing in the book of nature—whether encoded in a cloud, engraved on a leaf, or printed on the page—the messages in a bottle washed ashore from the shipwreck of what was once a distant star. The tone of urgency in the poet’s voice is well met with the ever more frequent reports of anomaly in the biosphere, of prodigies and portents on the horizons of scientific study—the Arctic Ocean warming more rapidly than the Mediterranean, a lamb born in New Zealand with seven legs, haystacks in Australia subject to high rates of spontaneous combustion, the Nile perch waging total war against the native species in Lake Victoria, a robot that recognizes itself in a mirror, Formosan termites dismantling the French Quarter in New Orleans, a dolphin schooled to sing the theme song from Batman.

The media upgrade the bulletins to terror alerts analogous to the statue spouting blood in the second act of Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar, the evil omens and the “strange impatience of the heavens” that pointed to a climate change in Rome induced by the presence of an unnatural tyrant. In place of great Caesar bestriding the narrow world like a colossus, maybe we have as surrogate the global industrial economy devouring the earth and all its progeny; but I’m less frightened by the prospect of boiling seas and disappearing forests than by the view into the abyss of my own ignorance, which is a spectacle equivalent in scale to one of Albert Bierstadt’s paintings of the nineteenth-century California wilderness. I open the book of nature on a page written in the alphabet of the double helix or come across the photograph of a 646-pound catfish hauled out of the Mekong River, and I know that I’m confronted with what Edmund Spenser likened to the “wide womb of the world” where lies in hateful darkness “An huge eternal Chaos.” If I could get what the writing means, learn with Wang Yucheng to read the “devious and fathomless” designs hidden in seemingly carefree clouds, or with Richard Feynman come to see in nature “simplicity and therefore a great beauty,” maybe then I’d know where, on the human genome map or in the Great Chain of Being, to place the singing dolphin and the self-regarding robot.

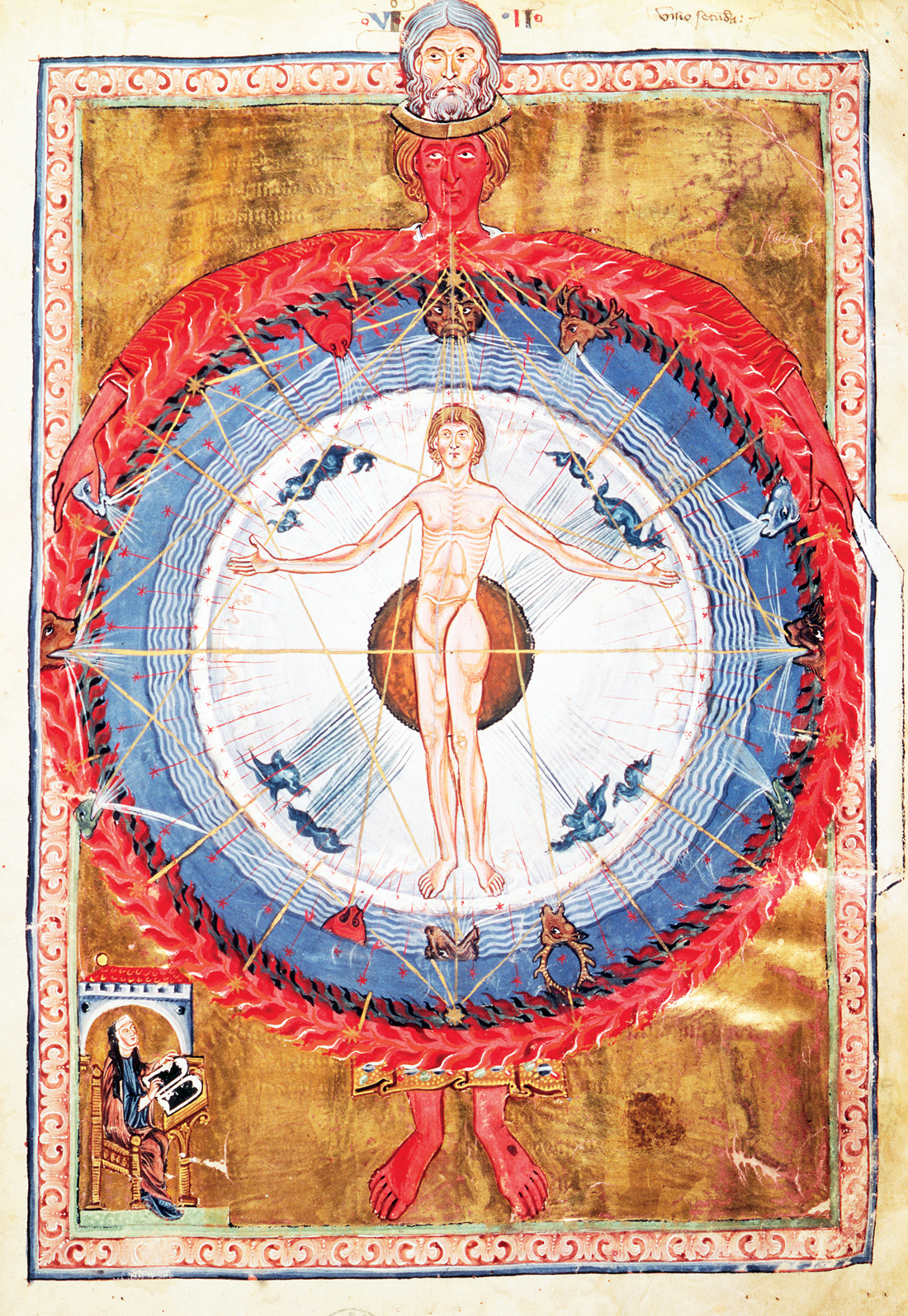

Man as the center of the universe, illustration from De Operatione Dei, by Saint Hildegard of Bingen, c. 1200. Biblioteca Statale, Lucca, Italy.

The texts in this issue of Lapham’s Quarterly go in search of an understanding of what we mean by nature, ask where to mark the boundaries between mind and matter, body and soul, the human and the nonhuman, between what’s out there in the woods and what’s in here with the endorphins and the organelles. Absent an answer to the questions, I don’t know how we call off the dogs of planetary ruin. The steadily multiplying world population (projected to increase from 6.5 billion to 9.1 billion people by 2050) is likely to impose unbearable burdens on increasingly scarce supplies of earth, air, fire, and water. The arithmetic suggests that we have no way of avoiding calamity without first giving up our belief that somehow there is an irreconcilable difference (substantive and spiritual as well as moral and aesthetic) between what is “natural” and what is “artificial.”

The separation of powers is one that I’ve never managed to recognize as immutable or divinely ordained, probably because my acquaintance with uncorrupted wilderness is for the most part second-hand, literary rather than operational. As a boy in California before World War II, I looked for the intimations of immortality in the novels of Joseph Conrad and Herman Melville instead of in the flight of birds and the flowering of trees. Once or twice I was sent on excursions to the Yosemite Valley, but “the divine manuscript” that John Muir found in its rocks and waterfalls might as well have been written in Egyptian hieroglyphs. The view of the headlands separating the entrance to San Francisco Bay I thought much improved by the intervention of the Golden Gate Bridge, the architecture of the city’s opera house more impressive than the giant redwood trees standing around in the fog three hundred miles to the north.

At school and college in Connecticut, I was introduced to Thoreau’s journals and Emerson’s essays, the canonical American scriptures that clothe the wilderness in the vestments of sacred shrine and store of virtue. What I thought wonderful was the play and force of the authors’ imaginations; the transcendence tended to go missing on the forced marches through the autumn woods in company with a faculty representative who, pausing from time to time on a windswept promontory or beside a stagnant pond, invited us to stand quietly and behold the awe. I never doubted that it was there, in plain sight and as big as Mexico, but usually I was scraping mud off my shoes, and before I could get myself turned in the right direction, the great god Pan had come and gone.

Which isn’t to say that I stand unmoved before the sight of the rising or the setting sun, indifferent to the crying of a loon or the mystery of sand, only that the wonders of nature I find no more or less miraculous than the products of civilization and its discontents. Whitman expresses the thought in

Drum-Taps, appreciative of the messages to be found in “serene-moving animals” and the “trellis’d grape” but adding to his list of marvels “shores and wharves heavy-fringed with black ships!…The life of the theater, barroom, huge hotel…”

Whitman’s willingness to see the beauty in a city street runs counter to the sermons of our own more zealous preachers of the environmental gospel. Appalled by the immense damage done to God’s green earth by mankind’s invasions of its privacy, they draw so severe a distinction between what is “natural” (the good, the true, and the beautiful) and what is “artificial” (wicked, man-made, false) that when inflamed by sentiments of a match with those of Robinson Jeffers and George Marsh, they equate humanity with vermin, civilization with disease. Fond thoughts of the purifying fire soon to descend from heaven blind them to the only hope of saving Tuvalu and the whales. Attribute to mankind the sins of pride, envy, gluttony, and sloth, as well as limitless reserves of farm-fresh stupidity and virgin greed, and it’s no trouble to make a long list of horrific consequences both intended and unintended—carbon dioxide degrading the atmosphere, mercury in the rivers, acid in the rain, disintegrating coral reefs and drowning polar bears. All true and not so beautiful, but how do we come to count the costs, much less learn to correct the mistakes, if not by means both man-made and corruptible?

Last winter’s reports of illegal drugs enhancing the performance of high-priced baseball players so stimulated the sale of tabloid scandal that it prompted a letter to the New York Times from a reader henceforth unwilling to let his children participate in competitive sports for fear of exposing them to an environment disgraced with unnatural additives. I admired the parent’s resolve but wondered where in the society he could find it safe to take the kids. Not to a local supermarket stocked with chemically preserved popcorn; not to a nearby hospital or to the neighborhood movie theater presenting computer-generated animations programmed to act like movie stars and movie stars made up to look like robots; not into an Internet chat room frequented by jaded algorithms and naked avatars.

In one way or another and to greater or lesser extents, the whole of our environment—peach orchards, oil wells, iPods, terrorists, tomatoes organic and inorganic, Barack Obama and Osama bin Laden, aquatic plants, downtown Shanghai, Russian oligarchs and Turkish racing pigeons, James Bond, anabolic steroids, Colorado mountain dew, National Geographic, and the cave paintings at Lascaux—is a virtual reality, fabricated by the hand and mind of man. If it is in the nature of beavers to build dams, and of glaciers to cast off icebergs, so it is in the nature of man to compose operas, design cows, and set in motion the beating of Vice President Dick Cheney’s cybernetic heart. We shape our tools, and our tools shape us, our technologies embarked on a voyage of evolution by accelerated means, reconfiguring their sense and sensibilities in ways similar to those by which amphibians become apes, apes change into Mormon choirs.

“In wildness,” said Thoreau, “is the preservation of the world,” which is no doubt true if by wildness, together with the caverns measureless to man through which ran the sacred river Alph, we also mean the uncharted deeps of the human mind from which spring, as naturally as does a chicken from an egg, genetically modified apple seeds, the USS Abraham Lincoln, the recombinations of chromosomes, home-grown and laboratory-tested.

The readings from the book of nature in this issue of Lapham’s Quarterly don’t lend themselves to executive summary. The messages in the bottle drift ashore at too many points of the compass (a beach on Cape Cod in 1928, a garden in seventeenth-century Japan, under a volcano in first-century Pompeii, under a microscope in Cambridge in 1953) to allow for their arrangement into anything other than broad categories reflecting the sight lines in the eye of the beholder. The contributors to the pages in “Howling Wilderness” discover in nature the colossal power that commands worship and instills fear; those in “Gardens of Earthly Delight” cultivate the notion, proposed in the Book of Genesis and seconded by Cicero, that nature is man’s servant. The notes and observations in “Terra Incognita” suggest, as does Annie Dillard in Virginia contemplating the abrupt disappearance of a hapless frog, that “we don’t know what’s going on here.”

Under all the three headings, the writing bears out the truth of

Goethe’s observation that nature is the only artist, dwelling in man and “she in them,” the wonder of her collected works formed by their reflections in the mirrors of the human imagination. Nature is what we do for a living, a work in progress as subject to revision in our states of consciousness as in our nucleic acids and somatic cells. The more beautiful questions demand the more beautiful answers, and if we can learn to ask them, we stand a chance of steering clear of shipwreck on our jury-rigged and not so distant star.