Honesty, for me, is usually the worst policy imaginable.

—Patricia Highsmith, 1960Teaching Distrust

Herman Melville invents confidence.

In the middle of the gentleman’s cabin burned a solar lamp, swung from the ceiling, and whose shade of ground glass was all round fancifully variegated, in transparency, with the image of a horned altar, from which flames rose, alternate with the figure of a robed man, his head encircled by a halo. The light of this lamp, after dazzlingly striking on marble, snow-white and round—the slab of a center table beneath—on all sides went rippling off with ever-diminishing distinctness, till, like circles from a stone dropped in water, the rays died dimly away in the furthest nook of the place.

Here and there, true to their place, but not to their function, swung other lamps, barren planets, which had either gone out from exhaustion, or been extinguished by such occupants of berths as the light annoyed, or who wanted to sleep, not see.

By a perverse man, in a berth not remote, the remaining lamp would have been extinguished as well, had not a steward forbade, saying that the commands of the captain required it to be kept burning till the natural light of day should come to relieve it. So the lamp—last survivor of many—burned on, inwardly blessed by those in some berths, and inwardly execrated by those in others.

Keeping his lone vigils beneath his lone lamp, which lighted his book on the table, sat a clean, comely, old man, his head snowy as the marble, and a countenance like that which imagination ascribes to good Simeon, when, having at last beheld the master of faith, he blessed him and departed in peace. From his hale look of greenness in winter, and his hands ingrained with the tan, less, apparently, of the present summer, than of accumulated ones past, the old man seemed a well-to-do farmer, happily dismissed, after a thrifty life of activity, from the fields to the fireside—one of those who, at threescore and ten, are fresh hearted as at fifteen; to whom seclusion gives a boon more blessed than knowledge, and at last sends them to heaven untainted by the world, because ignorant of it.

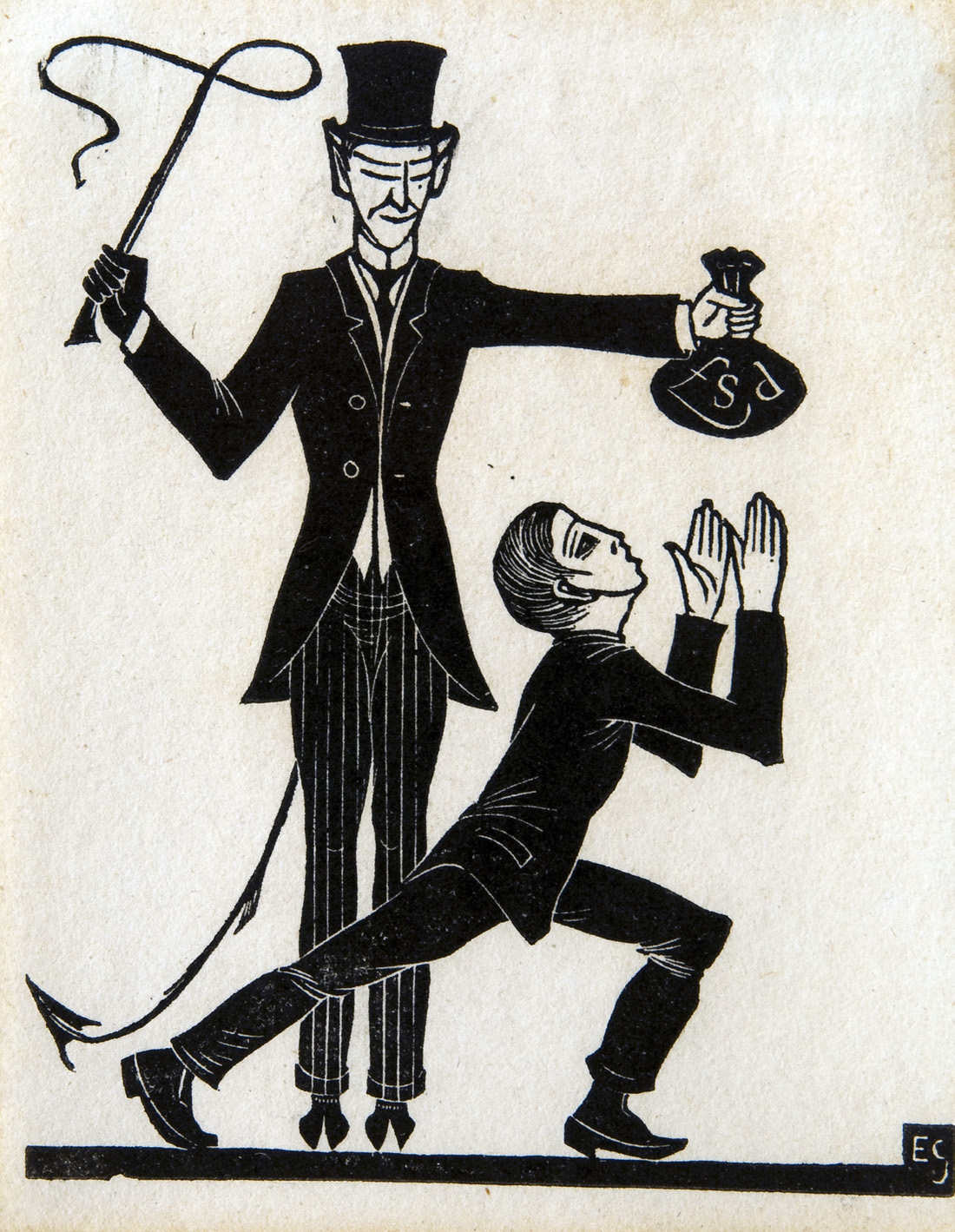

The Money Bag and the Whip, by Eric Gill, 1915. © Private Collection, Bridgeman Images.

Redolent from the barbershop, as any bridegroom tripping to the bridal chamber might come, and by his look of cheeriness seeming to dispense a sort of morning through the night, in came the cosmopolitan; but marking the old man, and how he was occupied, he toned himself down, and trod softly, and took a seat on the other side of the table, and said nothing. Still, there was a kind of waiting expression about him.

“Sir,” said the old man, after looking up puzzled at him a moment, “sir,” said he, “one would think this was a coffeehouse, and it was wartime, and I had a newspaper here with great news, and the only copy to be had, you sit there looking at me so eager.”

“And so you have good news there, sir—the very best of good news.”

“Too good to be true,” here came from one of the curtained berths.

“Hark!” said the cosmopolitan. “Someone talks in his sleep.”

“Yes,” said the old man, “and you—you seem to be talking in a dream. Why speak you, sir, of news, and all that, when you must see this is a book I have here—the Bible, not a newspaper?”

“I know that; and when you are through with it—but not a moment sooner—I will thank you for it. It belongs to the boat, I believe—a present from a society.”

“Oh, take it, take it!”

“Nay, sir, I did not mean to touch you at all. I simply stated the fact in explanation of my waiting here—nothing more. Read on, sir, or you will distress me.”

This courtesy was not without effect. Removing his spectacles, and saying he had about finished his chapter, the old man kindly presented the volume, which was received with thanks equally kind. After reading for some minutes, until his expression merged from attentiveness into seriousness, and from that into a kind of pain, the cosmopolitan slowly laid down the book, and turning to the old man, who thus far had been watching him with benign curiosity, said: “Can you, my aged friend, resolve me a doubt—a disturbing doubt?”

“There are doubts, sir,” replied the old man, with a changed countenance, “there are doubts, sir, which, if man have them, it is not man that can solve them.”

“True; but look, now, what my doubt is. I am one who thinks well of man. I love man. I have confidence in man. But what was told me not a half hour since? I was told that I would find it written—‘Believe not his many words—an enemy speaketh sweetly with his lips’—and also I was told that I would find a good deal more to the same effect, and all in this book. I could not think it; and, coming here to look for myself, what do I read? Not only just what was quoted, but also, as was engaged, more to the same purpose, such as this: ‘With much communication he will tempt thee; he will smile upon thee, and speak thee fair, and say, What wantest thou? If thou be for his profit he will use thee; he will make thee bear, and will not be sorry for it. Observe and take good heed. When thou hearest these things, awake in thy sleep.’ ”

“Who’s that describing the confidence man?” here came from the berth again.

“Awake in his sleep, sure enough, ain’t he?” said the cosmopolitan, again looking off in surprise. “Same voice as before, ain’t it? Strange sort of dreamy man, that. Which is his berth, pray?”

“Never mind him, sir,” said the old man anxiously, “but tell me truly, did you, indeed, read from the book just now?”

“I did,” with changed air, “and gall and wormwood it is to me, a truster in man; to me, a philanthropist.”

“Why,” moved, “you don’t mean to say, that what you repeated is really down there? Man and boy, I have read the good book this seventy years, and don’t remember seeing anything like that. Let me see it,” rising earnestly, and going round to him.

“There it is; and there—and there”—turning over the leaves, and pointing to the sentences one by one; “there—all down in the ‘Wisdom of Jesus, the Son of Sirach.’ ”

“Ah!” cried the old man, brightening up, “now I know. Look,” turning the leaves forward and back, till all the Old Testament lay flat on one side, and all the New Testament flat on the other, while in his fingers he supported vertically the portion between, “look, sir, all this to the right is certain truth, and all this to the left is certain truth, but all I hold in my hand here is apocrypha.”

“Apocrypha?”

“Yes; and there’s the word in black and white,” pointing to it. “And what says the word? It says as much as ‘not warranted’; for what do college men say of anything of that sort? They say it is apocryphal. The word itself, I’ve heard from the pulpit, implies something of uncertain credit. So if your disturbance be raised from aught in this apocrypha,” again taking up the pages, “in that case, think no more of it, for it’s apocrypha.”

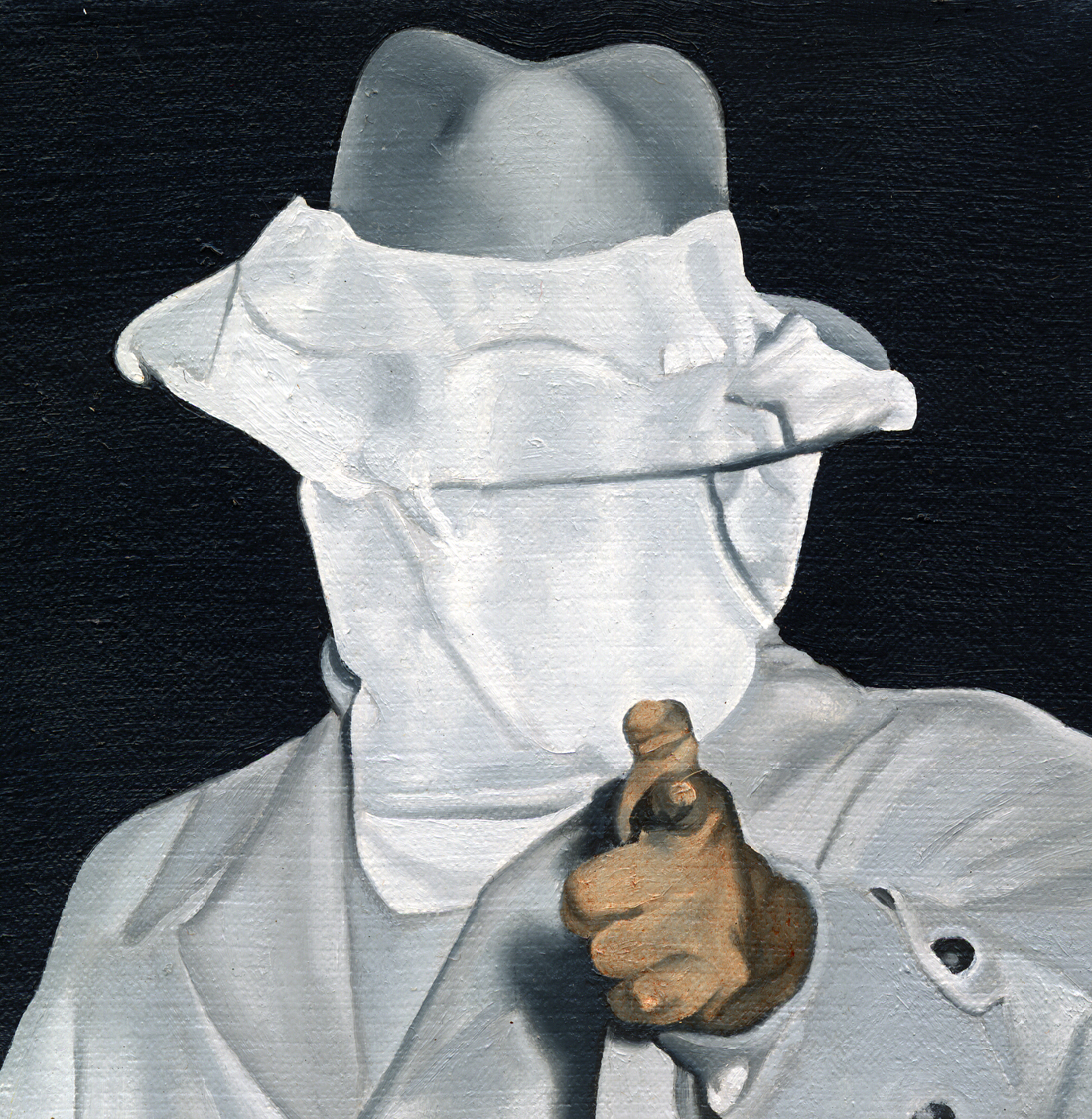

Worst Case Scenario (VII), by Dotty Attie, 2013. © Dotty Attie, courtesy the artist and P.P.O.W Gallery, New York.

“But, sir,” resuming, “I cannot tell you how thankful I am for your reminding me about the apocrypha here. For the moment, its being such escaped me. Fact is, when all is bound up together, it’s sometimes confusing. The uncanonical part should be bound distinct. And, now that I think of it, how well did those learned doctors who rejected for us this whole book of Sirach. I never read anything so calculated to destroy man’s confidence in man. This son of Sirach even says—I saw it but just now: ‘Take heed of thy friends’; not, observe, thy seeming friends, thy hypocritical friends, thy false friends, but thy friends, thy real friends—that is to say, not the truest friend in the world is to be implicitly trusted. Can Rochefoucauld equal that? I should not wonder if his view of human nature, like Machiavelli’s, was taken from this Son of Sirach. And to call it wisdom—the Wisdom of the Son of Sirach! Wisdom, indeed! What an ugly thing wisdom must be! Give me the folly that dimples the cheek, say I, rather than the wisdom that curdles the blood. But no, no; it ain’t wisdom; it’s apocrypha, as you say, sir. For how can that be trustworthy that teaches distrust?”

“I tell you what it is,” here cried the same voice as before, only more in less of mockery, “if you two don’t know enough to sleep, don’t be keeping wiser men awake. And if you want to know what wisdom is, go find it under your blankets.”

“Wisdom?” cried another voice with a brogue; “arrah and is’t wisdom the two geese are gabbling about all this while? To bed with ye, ye divils, and don’t be after burning your fingers with the likes of wisdom.”

“We must talk lower,” said the old man; “I fear we have annoyed these good people.”

Herman Melville

From The Confidence Man. With money from his father-in-law, Melville purchased a Massachusetts farmhouse called Arrowhead, where, in a room with a view of Mount Greylock, he completed Moby Dick in 1851, dedicating it to his friend and neighbor Nathaniel Hawthorne. For the mise en scène of The Confidence Man—the term had first appeared, in reference to a New York City criminal, in 1849—Melville relied on secondhand accounts, for it is believed he only once, in 1840, traveled on the Mississippi River. The book was published on April Fool’s Day in 1857.