To be too conscious is an illness—a real thoroughgoing illness.

—Fyodor Dostoevsky, 1864When the Spirit Moves You

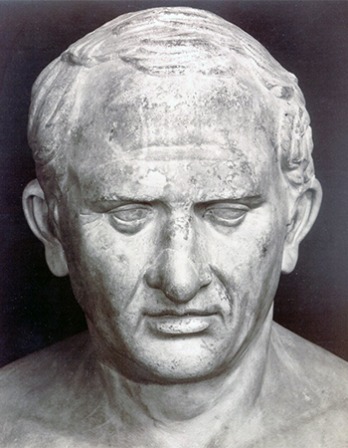

Socrates delivers a muse you can use.

Ion: I am conscious in my own self, Socrates, and the world agrees with me in thinking that I speak better and have more to say about Homer than any other man. But I do not speak equally well about other subjects—tell me why.

Socrates: The gift you possess of speaking excellently about Homer is not a skill but an inspiration. There is a divinity moving you like the force contained in the stone Euripides calls a magnet. This stone not only attracts iron rings but also imbues them with the power of attracting other rings. Sometimes you may see a number of pieces of iron and rings suspended from one another, forming quite a long chain—and all of them derive their power of suspension from the original stone. This is like how the Muse first of all inspires men herself, and from these inspired ones is suspended a chain of other people who take inspiration. For all good poets, epic as well as lyric, compose their beautiful poems not by skill but because they are inspired and possessed.

Like ecstatic dancers who are not in their right mind, the lyric poets are not in their right mind when they are composing their beautiful strains. Falling under the power of music and meter, they are inspired and possessed, like bacchic maidens who draw milk and honey from the rivers when they are under the influence of Dionysus but not when they are in their right mind. The soul of the lyric poet does the same, as they themselves say—they tell us that they bring songs from honeyed fountains, culling them out of the gardens and dells of the Muses, like bees winging their way from flower to flower. And this is true. For the poet is a light, winged, holy thing, and there is no invention in him until he has been inspired and is out of his senses, and the mind is no longer in him. When he has not attained this state, he is powerless and is unable to utter his oracles.

Into the New World, by Jamie Baldridge, 2009–11. © Jamie Baldridge, courtesy the artist.

A god takes away the minds of poets and uses them as his ministers just as he uses diviners and holy prophets—in order that we who hear them know that they who utter these priceless words in a state of unconsciousness are speaking not of themselves but that the god himself is the speaker, and that through them he is conversing with us. Tynnichus the Chalcidian affords a striking instance of what I am saying. He wrote nothing that anyone would care to remember except the famous poem that is in everyone’s mouth, one of the finest poems ever written. It is simply an invention of the Muses, as he himself says. The god would seem to indicate to us and not allow us to doubt that these beautiful poems are not human or the work of man but divine and the work of a god, and that the poets are only the interpreters of the gods by whom they are severally possessed. Was not this the lesson the god intended to teach when he sang the best of songs through the mouth of the worst of poets?

Ion: Yes, indeed, Socrates.

Socrates: And you rhapsodes are the interpreters of the poets?

Ion: Again, you are right.

Socrates: Then you are the interpreters of interpreters?

Ion: Precisely.

Socrates: And when you produce the greatest effect on the audience in the recitation of some striking passage, such as the apparition of Odysseus leaping forth on the floor, recognized by the suitors and casting his arrows at his feet, or the description of Achilles rushing at Hector, or the sorrows of Andromache, Hecuba, or Priam, are you in your right mind? Are you not carried out of yourself, and does not your soul in an ecstasy seem to be among the persons or places of which you are speaking, whether they are in Ithaca or in Troy or whatever may be the scene of the poem?

Ion: That is clear to me, Socrates. I must frankly confess that at the tale of pity, my eyes are filled with tears, and when I speak of horrors, my hair stands on end and my heart throbs.

Socrates: Well, Ion, and what are we to say of a man who at a sacrifice or festival, when he is dressed in holiday attire and has golden crowns on his head, appears weeping or panic-stricken in the presence of more than twenty thousand friendly faces when there is no one doing him any wrong—is he in his right mind or not?

Ion: No, indeed, Socrates, I must say that, strictly speaking, he is not in his right mind.

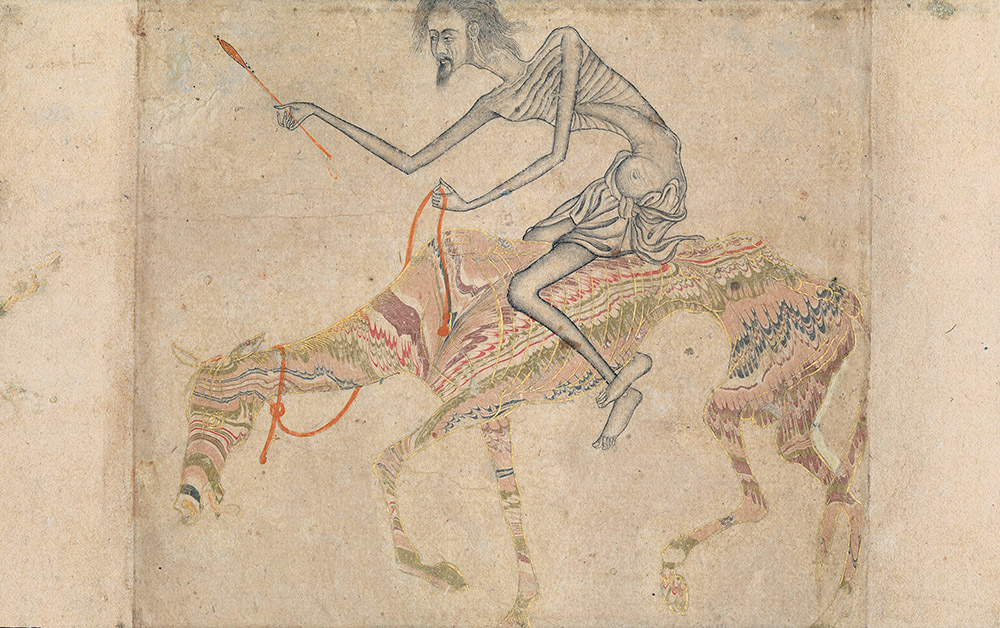

Emaciated Horse and Rider, India, c. 1625. © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund, 1944. Symbols of bodily desire in Sufi imagery, horses are often shown starved and beaten.

Socrates: And are you aware that you produce similar effects on most of the spectators?

Ion: Only too well. I look down on them from the stage and behold the various emotions of pity, wonder, sternness, stamped on their faces when I am speaking.

Socrates: And do you know that the spectator is the last of the rings that, as I am saying, receive the power of the original magnet from one another? The rhapsode like yourself and the actor are intermediate links, and the poet himself is the first of them. Through all of these, the god sways the souls of men in any direction he pleases and makes one man hang down from another. Thus there is a vast chain of dancers and masters and undermasters of choruses suspended—as if from a magnet—at the side of the rings that hang down from the Muse. And every poet has some Muse from whom he is suspended, and by whom he is said to be possessed, which is nearly the same thing, for he is taken hold of. And from these first rings, which are the poets, depend others. Some derive their inspiration from Orpheus, others from Musaeus, but the greater number are possessed and held by Homer.

It is far, far better and much safer to have a firm anchor in nonsense than to put out on the troubled seas of thought.

—John Kenneth Galbraith, 1958You are one of these, Ion, and are possessed by Homer. When anyone repeats the words of another poet, you go to sleep and know not what to say, but when anyone recites a strain of Homer, you wake up in a moment, and your soul leaps within you, and you have plenty to say. It is not by skill or knowledge about Homer that you say what you say but by divine inspiration and by possession—just as ecstatic dancers, too, have a quick perception of only that strain which is appropriated to the god by whom they are possessed, and have plenty of dances and words for that but take no heed of any other. And you, Ion, when the name of Homer is mentioned have plenty to say, and have nothing to say of others. You ask, “Why is this?” The answer is that you praise Homer not by skill but by divine inspiration.

Plato

From Ion. On the road back home from winning a rhapsode competition in the city of Epidaurus, Ion runs into Socrates, who engages him in this philosophical discussion. “On what part of Homer do you speak well?” Socrates asks Ion later in the dialogue. “Surely not about every part.” Ion bristles in response: “There is no part, Socrates, about which I do not speak well, of that I can assure you.” Born into a distinguished family, Plato founded the Academy on the outskirts of Athens in 387 BC.