I behold among you Alexandrians not merely Greeks and Italians and people from neighboring Syria, Libya, Cilicia, nor yet Ethiopians and Arabs from more distant regions, but even Bactrians and Scythians and Persians and a few Indians—and all these help to make up the audience in your stadium and sit beside you on each occasion. Therefore, while you are watching three or four charioteers, you yourselves are being watched by countless Greeks and barbarians as well.

What then do you suppose those people say when they have returned to their homes at the ends of the earth? Do they not say, “We have seen a city that in most respects is admirable and a spectacle that surpasses all human spectacles, and yet,” they will add, “it is a city that is mad over music and horse races and in these matters behaves in a manner entirely unworthy of itself. For the Alexandrians are moderate enough when they offer sacrifice or stroll by themselves or engage in their other pursuits, but when they enter the theater or the stadium, just as if drugs that would madden them lay buried there, they lose all consciousness of their former state and are not ashamed to say or do anything that occurs to them. And what is most distressing of all is that, despite their interest in the show, they do not really see, and, though they wish to hear, they do not hear, being evidently out of their senses and deranged—not only men but even women and children. And when the dreadful exhibition is over and they are dismissed, although the more violent aspect of their disorder has been extinguished, still at street corners and in alleyways, the malady continues throughout the entire city for several days; just as when a mighty conflagration has died down, you can see for a long time not only the smoke but also some portions of the buildings still aflame.” Moreover, some Persian or Bactrian is likely to say, “We ourselves know how to ride horses and are held to be just about the best in horsemanship”—for they cultivate that art for the defense of their empire and independence—“but for all that, we have never behaved that way or anything like it.”

And take heed lest these people prove to have spoken more truthfully about you than Anacharsis the Scythian is said to have spoken about the Greeks—for he was held to be one of the sages, and he came to Greece, I suppose, to observe the customs and the people. Anacharsis said that in each city of the Greeks there is a place set apart in which they act insanely day after day—meaning the gymnasium—for when they go there and strip off their clothes, they smear themselves with a drug. “And this,” said he, “arouses the madness in them; for immediately some run, others throw each other down, others put up their hands and fight an imaginary foe, and others submit to blows. And when they have behaved in that fashion,” said he, “they scrape off the drug and straightaway are sane again, and now on friendly terms with one another, they walk with downcast glance, being ashamed at what has occurred.”

Anacharsis was jesting and making sport about no trifling matter, it seems to me, when he said these things, but what might a visitor say about yourselves? For as soon as you get together, you set to work to box and shout and hurl and dance—smeared with what drug? Evidently with the drug of folly, as if you could not watch the spectacle sensibly! For I would not have you think I mean that even such performances should not take place in cities—for perhaps they should, and it may be necessary, because of the frailty of the masses and their idle habits. But as things are now, if one of the charioteers falls from his chariot, you think it terrible and the greatest of all disasters, whereas when you yourselves fall from the decorum that befits you and from the esteem you should enjoy, you are unconcerned.

©1932 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College. Used with permission of the publishers and the Trustees of the Loeb Classical Library.

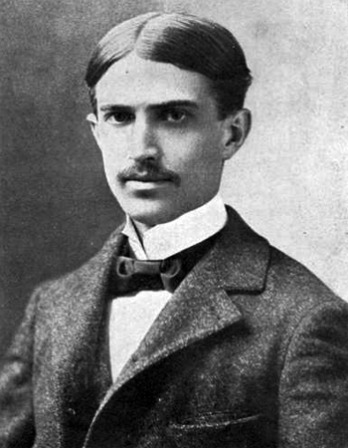

From “Discourse 32.” Banished for political reasons from both Bithynia and Italy by Domitian in 82, Dion wandered around the Black Sea region for fourteen years. Upon the emperor’s death, he returned to Rome, where he became a successful rhetorician.

Back to Issue