The law looks at no one’s face.

—Gabriel Okara, 1964Separation of Power

To make a more perfect union, don’t look to the Founding Fathers.

By William Hogeland

U.S. Supreme Court building, 2011. Photograph by Joe Ravi (CC-BY-SA 3.0).

The rule of law is making news. Representative headlines include “Trump’s All-Out Attack on the Rule of Law” (The Nation), “An Open Door to Anarchy: President Trump Is a Threat to America’s Rule of Law and its National Security” (U.S. News & World Report), and “Trump’s Latest Attack on the Rule of Law” (Washington Post). The revived phrase usefully distills John Adams’ favorite definition of a republic, “a government of laws and not of men.” A government not, that is, arbitrary but regular, with benefits not personal but public, proceeding by written-down precept, not ad hoc impulse, thus sheltering rights from changes of party and whims of personality. Keeping the rule of law in mind can help cut through the Trump administration’s dizzying incoherence to arrive at an underlying fault: total disdain, sometimes barely covert, sometimes brazen, for the restraints legally imposed on the office. Using power to satisfy personal desires, enrich friends and family, put on shows for supporters, and punish enemies and critics sets this administration at odds with values that many Americans, of conflicting political persuasions, have long believed run deeper than political disagreement.

Not that our government has always or even often enough operated according to the rule of law. The current president has taken violation to a degree of heedlessness so grotesque that we can’t be sure he knows he’s violating anything. That degree, it turns out, puts us through the looking glass. We may never have known before how deeply rooted a sense of respect for the concept of the rule of law has been to everything we hope that our government can be. When calling a republic a government of laws and not of men, Adams was paraphrasing seventeenth-century writer James Harrington, whose thinking about tyranny and liberty in the context of England’s Puritan revolution had a powerful influence on the country’s founders. Harrington called the precept “ancient,” by which he meant something like “fundamental to legitimate order.” The American founders, adopting that view, did something Harrington couldn’t. They put the rule of law into practice, forming a new nation explicitly on its basis.

It’s not surprising, therefore, that the founders’ Constitution—the main body, ratified in 1788, and the first twelve amendments, ratified 1791–1804—has become a focus of optimism about the rule of law in the public discourse of resistance to Trump. It’s thanks to the founders’ regard for the rule of law that the Constitution gives us, for one thing, a process for impeaching the president for “high crimes and misdemeanors.” The founders even specified one such crime or misdemeanor, according to Laurence Tribe and other constitutional lawyers, in the emoluments clause. Most of us have had little reason for appreciating that clause before. Tribe accuses Trump of violating it by doing private business with foreign actors while holding office.

But the constitutional element receiving the most attention in this crisis has to do with how we govern law itself, a rule of law for the rule of law: the federal judicial branch’s independence from the executive and legislative branches. Judicial independence has enabled, for example, federal judges to block and to uphold execution of Trump’s ban on immigrants from a select list of countries, and to prevent the administration from rescinding wholesale the DACA program on which nearly 700,000 young immigrants rely. Reverberations of a clash between Trump and the federal judiciary go well beyond the ups and downs of those cases. In response to the judges’ decisions, Trump has attacked not just the decisions, and not just the judges, but judicial independence itself.

To the American founders, by stark contrast, there was no Constitution of the United States without that independence. Adams, explaining the structure of Massachusetts government in 1779, yoked judicial independence explicitly to his favored definition of a republic. “The legislative department,” he wrote, “shall never exercise the executive and judicial powers, or either of them: the executive shall never exercise the legislative and judicial powers, or either of them: the judicial shall never exercise the legislative and executive powers, or either of them: to the end it may be a government of laws and not of men.” The novel thing in Massachusetts’ separation of powers—imitated in the national Constitution eight years later—was to institute what Trump has declared “unfair”: the judiciary as an independent branch of government.

Poor John. Anti-Trump forces rallying round judicial independence are focusing not on Adams but on Alexander Hamilton. While Broadway may have something to do with that, it was Hamilton—in the essays that he, James Madison, and John Jay published in 1787 and 1788, collected as The Federalist—who set out perhaps the most thorough founding-era argument for making the judiciary an independent branch of the national government. Hamilton’s Federalist 78, the most detailed of those essays, is now receiving much public appreciation. In a Washington Post opinion piece criticizing Trump’s attack on federal judges, Randy Barnett recently appealed to 78, quoting the view Hamilton expressed there that an independent judiciary is “an indispensable ingredient” of the Constitution. The Economist has cited Hamilton on the matter, too. And in late 2017, the Georgetown University law professor William Michael Treanor published online “The Genius of Hamilton and the Birth of the Modern Theory of the Judiciary,” his chapter dedicated to Federalist 78, forthcoming in The Cambridge Companion to “The Federalist”. Treanor gives Hamilton’s essay credit for the near-solo creation of the modern judiciary.

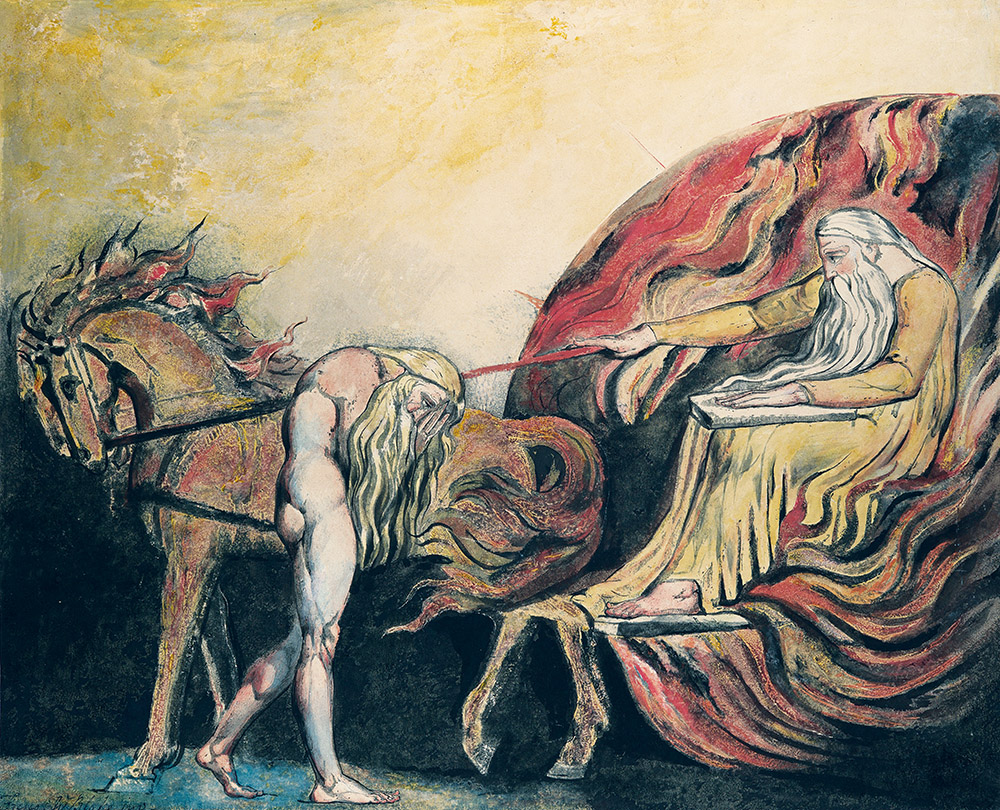

God Judging Adam, by William Blake, c. 1795. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Rogers Fund, 1916.

Yet in lauding Federalist 78, resistance to Trump stumbles into divots, even potholes, in the landscape of an American civics on which any effective resistance would have to rely. The anti-Trump intelligentsia is reading Hamilton’s essay out of historical and political contexts, the founders’ and ours. Confusion begins in misconstruing the essay’s purpose. Hamilton was writing neither a meditation on judiciaries nor a guide to ours. While generations of judges have treated The Federalist as scholarship, precedent, even transcendent truth, the essays are works of persuasion, cranked out in hopes of convincing the delegates of New York to support ratification of the proposed Constitution. There was no federal judiciary when Hamilton wrote essay 78, no high or low courts, no specified number of Supreme Court justices, no federal case law, nothing but a few sentences stating that such a system should exist and—the kicker—making it independent of the other two branches. Hamilton’s goal in 78 was to demolish recently published arguments on the dangers of making the judiciary independent. He wanted to get the Constitution ratified, with the judicial branch a covalent part of government.

Context for that effort involves Hamilton’s and his colleagues’ perception that in judicial independence lay a mechanism not for promoting democracy but for the reverse: checking what seemed to be potential dangers posed by the lower house of the proposed national legislature. Hamilton’s persistent concern was to defeat what he and others of his class called the “leveling” impulse: efforts by lower orders to equalize society economically by undermining the value of property and investment, and thus, went the prevailing line of elite thought, destroying liberty itself. Where modern liberal thinking tends to equate freedom with a high degree of social equality, to Adams, Hamilton, Washington, Madison, and others, equality already seemed, in 1789, to be shattering traditional norms, devaluing elite holdings, and paving the way for the despotism that, in their reading of history, inevitably follows from attacks on property. The 1780s had seen populist agitation for debt relief, price controls, progressive taxation, access to credit, and the abolition of property qualifications for the voting franchise. Under pressure from working-class populists, state legislatures had been passing monetary laws that gave advantage to debtors, artisans, small farmers, and laborers. In Pennsylvania, there had even been talk of capping by law the amount of property anyone could own. A desire to put an end to what elites saw as state-legislative abuse of that kind spurred the formation of a national government. Such abuse must certainly be prevented from infecting the proposed national legislature. Hence the pitch for judicial independence that Hamilton made in Federalist 78.

Making the judiciary so powerful was bound to be scary. Whig liberty types, reacting in the Harrington mode, feared any power that might defeat representation, traditionally the legal means of resisting sovereign encroachment on rights. What if a federal judge, for example, appointed for life by the executive, were to set aside a law passed by Congress on the basis that it was somehow “unconstitutional”? That scenario brought on nightmares of classic tyranny. These same men, however, were the elites of New York—that’s why Hamilton was addressing them. As creditors of their poorer neighbors, they harbored a fear of the leveling instinct as great as their fear of authoritarianism. Such a fear was bolstered ideologically by their certainty that the former always leads to the latter anyway. Republican gentlemen of the founding generation loved the tradition of representation. They hated the democratic results of representation going on in some of the states. Hence their bind.

A functioning police state needs no police.

—William S. Burroughs, 1959Hamilton offered a way out. Federalist 78 is characteristic of his brilliance not as a theoretician—he could take the most abstruse theory in a single bite and chew it any way he liked—but as a master of building paths to usher readers inevitably toward his conclusions. The historian Peter Charles Hoffer, reading Hamilton’s essays on the judiciary as an adroit walking-in of the novel power of judges to set aside laws, shows how the founder widely considered the least politic was capable here of concealment, cushioning, and timely revealing for maximum effect. The essay is marked by classic Hamiltonian tactics, by no means consistent with the notion prevailing among liberal admirers today, that the essay offers protection for hard-won democratic progress now under threat.

The central argument in 78 begins with an insistence that the might of an independent judiciary, supposedly so scary, is chimerical. The judicial branch won’t really be equal to the other two, Hamilton assures his readers; unlike Congress, it can’t create laws, and it has to rely on the presidency to enforce rulings. If the branch can become fearsome only in collaboration with another branch, all the more reason for separating it. A court this weak can never make itself superior to the legislature. Having tiptoed up to the land mine—the court’s controversial power to set aside legislative acts—Hamilton tells his readers there’s nothing to see there. He conjures a hypothetical scenario in which Congress passes an act undermining due process of law itself: an ex post facto law or bill of attainder, old legal tricks of arbitrary power loathed axiomatically by readers of the liberty literature. Who but the federal courts, Hamilton asks, would be in a position to push Congress back within constitutional bounds? Such a role would in no way set the court above Congress: “The power of the people”—the Constitution itself—“is superior to both.” So even in instances where this weakling court must flex its muscles, it can act only as an intermediary.

Hamilton has deftly dispelled fears. His judiciary is gasping for life in those areas where readers would be hypersensitive to arbitrary power and no more than an intermediary whenever invigorated temporarily for the sole purpose of preserving constitutionality. He now dangles before his audience certain potencies that he says have nothing to do with constitutionality. He notes, first, that an independent judiciary would stifle “legislative encroachments.” His audience would read that term as referring to legislation benefiting debtors, artisans, and poor farmers at the expense of property.

Employing the favored language of his class for describing social agitation, Hamilton asserts that an independent judiciary will mitigate:

those ill humors, which the arts of designing men, or the influence of particular conjunctures, sometimes disseminate among the people themselves, and which, though they speedily give place to better information, and more deliberate reflection, have a tendency, in the meantime, to occasion dangerous innovations in the government, and serious oppressions of the minor party in the community.

By dangerous innovations and serious oppressions he means populist fiscal laws; by the minor party he means the well-propertied. And he casts this judicial power to keep a stirred-up people down as the gift that keeps on giving. A legislature whose populist laws are repeatedly voided, Hamilton predicts, will give up even trying to pass them. That’s a vision the elites of New York could get behind. Hamilton reminds them that all virtuous, disinterested, considerate people—them—are aware of the deleterious effects on stability and virtue of the bad spirit irresponsibly aroused by demagogues in an otherwise reasonable people. An independent judiciary can obstruct that spirit—elites called it both “the mob” and “the democracy”—and even crush it altogether via the rule of law.

Everybody knows, at least on reflection, that Hamilton, Adams, and their colleagues weren’t democrats and egalitarians. The question is why today’s embattled liberalism, seeking protection for essential American institutions promoting equality and democracy, lauds Hamilton’s arguments for the legal suppression of equality and democracy. Just technically, most of 78 is immaterial at best to liberal hope and success. Blocking the attempted Muslim ban and the rescinding of DACA rely on a judicial power to check not Congress but the executive; in 78, Hamilton, a promoter of executive strength, only barely alludes to that power. Expanding equality came about in the twentieth century through the federal courts’ power to set aside oppressive state laws. In 78, Hamilton didn’t mention that power, referring only to potential excesses of Congress.

The Lawyer’s Last Circuit, by Thomas Rowlandson, 1802. Courtesy National Gallery of Art, Washington, Rosenwald Collection.

And the federal courts’ supposed weakness, emphasized to such reassuring effect by Hamilton, has played no role in the history of democratic progress. On the contrary, it’s possible to see twentieth-century democratic liberalism as having pinned all hopes on a superpowered judiciary, the court not so much intermediary but head umpire, knocking down undemocratic state laws and presidential overreach.

The rule of law that we’re now desperate to protect is stranger than we seem to want to know. Those praising the founders’ Constitution in opposition to Trump are leaving out something at once all-important and constitutionally weird: the far-reaching impact of the post–Civil War amendments—the Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth—written and ratified in hopes of ensuring racial equality before the law in a postslavery world. While that hope was defeated for many years, the amendments’ type was revolutionary. For the first time, individuals possessed constitutionally enforceable protections against their state governments. That shift, critical to the most elementary advances in democracy and equality—a protected right to vote, for example—reversed what had been the founders’ understanding of the Constitution’s purport.

A familiar brand of liberal civics disagrees, advancing an argument something like this: of course the founders, being human, couldn’t see democracy and equality coming, or even endorse them; they provided the structures enabling democracy and equality to emerge. In that story our national development is organic, if difficult, like the development of everything else living, the republic a tight blossom opening to full bloom only with time and struggle. Democracy and equality were invisible at first because they were coded in a seed, the founders’ premium on the rule of law. The Civil War, a trial by fire that ushered the nation into maturity, caused no fundamental constitutional disruption. The founding is alive, the letter of founding law now better conforming to the best in its spirit.

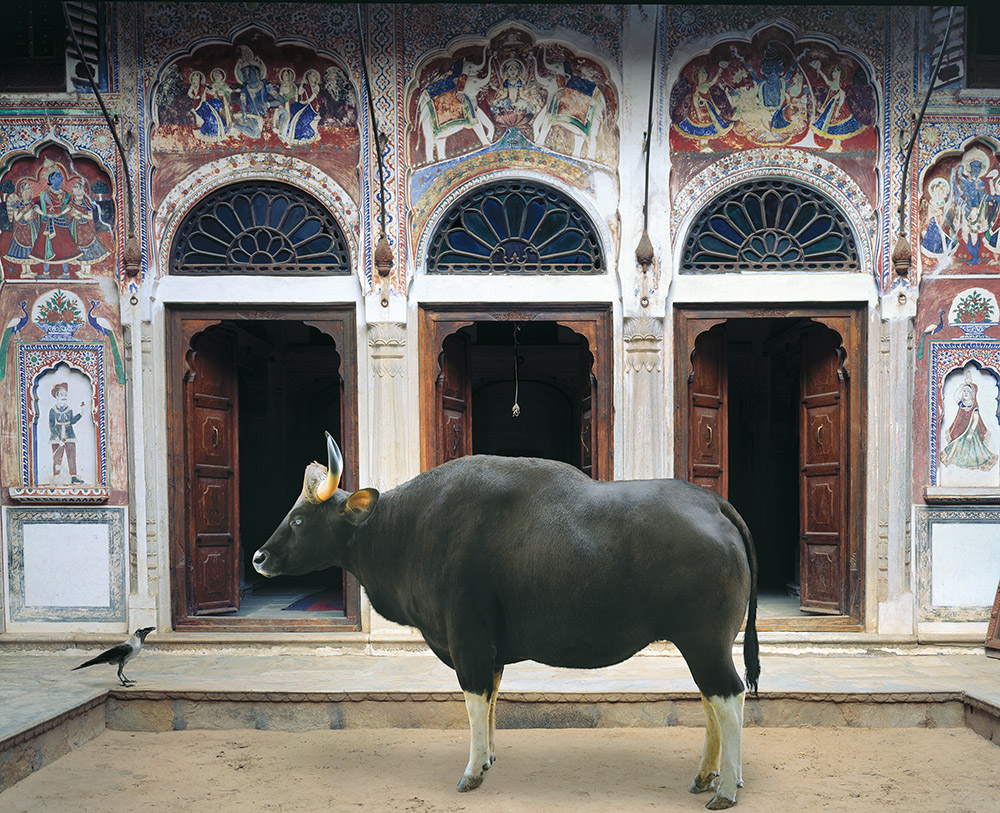

The Law of Dharma, by Karen Knorr, 2008–15. Print on Hahnemühle FineArt Pearl paper. © Karen Knorr, courtesy of the artist.

It’s fairly well-known that from the 1950s through the 1970s, Supreme Court decisions applied the Fourteenth Amendment’s due process and equal protection clauses to bring about a thoroughgoing renovation of American society, famously in Brown v. Board of Education, Loving v. Virginia, and Roe v. Wade, as well as in decisions upholding acts of Congress that promoted voting rights. While those decisions enforced equality in rights that the founders explicitly did not define as constitutionally protected, lesser-known and even stranger explosions set off by the post–Civil War amendments had already blown up important parts of the founders’ Constitution. Beginning in the 1920s, the meaning of some of the founders’ amendments—the first ten, which we call the Bill of Rights—changed not via the amendment process that the founders set out but by a judicial reading of the Fourteenth Amendment as embracing the first ten. Lawyers and scholars call the doctrine “incorporation,” connoting a smoothness belied by the havoc that incorporation has wreaked not only on the founders’ amendments but also on public understanding of American government. The belief that the founders’ Constitution goes on living is maintained only by ignoring how thoroughly incorporation demolished the spirit of certain elements of founding law, even while leaving the letter bewilderingly intact.

Everybody more or less accepts, for example, that state legislatures can’t pass laws violating freedom of the press. Because that freedom is protected by the First Amendment, such a law would exemplify what most people nowadays mean by unconstitutional. That’s the reverse of what the founders meant by unconstitutional, as underscored by a remark made by Thomas Jefferson in an 1804 letter to Abigail Adams. “While we deny that Congress have a right to control the freedom of the press,” Jefferson wrote, “we have ever asserted the right of the states, and their exclusive right, to do so.” A somewhat jarring assertion coming from our founding apostle of free speech.

Was he right? Did the First Amendment’s most famous language protect from Congress both an individual freedom to publish and a state power to censor? The Supreme Court said it did until 1925, when in considering matters that Jefferson couldn’t have envisioned, the justices realized that enforcing the Fourteenth Amendment’s due process clause requires extending First Amendment protections to citizens against their states. A good thing, too, many of us would say. But if Jefferson’s view reflected an understanding of the First Amendment’s scope, the effect of the 1925 ruling represents not a development but a cancellation of founding purpose. By the same token, thanks to judicial decisions of the 1940s, the First Amendment’s opening words, “Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion,” which used to mean “Congress shall neither establish a religion nor interfere with the states’ establishing religions,” now mean “Neither Congress nor the states shall establish religions,” an even starker reversal of the original meaning than extending protection of an individual right like speech. A note in the Harvard Law Review argues persuasively that the establishment clause in the First Amendment, when ratified, didn’t protect, even partially, an individual right; the clause’s sole focus was on protecting the states from federal interference in religious matters. Yet that protection was removed by federal action in a procedure not based on the founders’ process for amending the Constitution but invented by the independent judiciary. That’s a far cry from what Hamilton was talking about.

An unjust law is no law at all.

—Saint Augustine, 395Conservatives who complain about “activist judges” and “legislating from the bench” blame outcomes they don’t like on judicial misbehavior. Acknowledging the power of the Fourteenth Amendment to demolish big parts of the founders’ Constitution—both by incorporating the founders’ amendments and by protecting a host of individual rights from state lawmaking—would place conservatism in the position of objecting to the outcome of the Civil War itself. Racist extremists do that; mainstream conservatism has largely learned not to. Liberals, by contrast, celebrate outcomes of the Fourteenth’s wide-roaming might. Yet in construing the Constitution as a living development of the founders’ work, liberalism must pretend the branches have remained equal even while praising the judiciary’s cancellation of founding purposes.

We go on in a state of innocence more than a century out of date and a major cause of the crisis we’re in: if Adams was correct in thinking that a republic depends on an informed citizenry, he’d be all the more correct about a democracy. Our crisis makes clear that lacking a civics based in reality causes systems to break down. Such a civics would have to take into account the unsettling fact that we who recoil from regressive ideas like states’ rights to censor speech, establish religions, impose racial segregation, levy poll taxes, and prohibit abortions are recoiling not only from the founders’ antidemocratic thinking but also from the mechanics they deemed indispensable to liberty and believed they had hardwired, in part via the independent judiciary, into the nation’s rule of law. They were wrong. By rewiring the machine, we’ve made it at least potentially an American democracy.

But it has never been as operational as we’d like, and it’s been threatening to fail. It’s time to outgrow the fetish for founding philosophies of government and to accept how necessary it’s been to the emergence of democratic institutions to make a hash of the founders’ Constitution. We can be grateful for judicial independence and the impeachment process. We should know that presidents stopped doing private business, including with foreign powers, not because they feared the emoluments clause but because ethical standards have improved, not degraded, since the founding; actions we deem improper looked just fine to George Washington. It’s very late to renounce innocence, very late to begin building the clear-eyed civics that, had it ever existed, might have immunized this country from the most brazen threat so far to its rule of law.