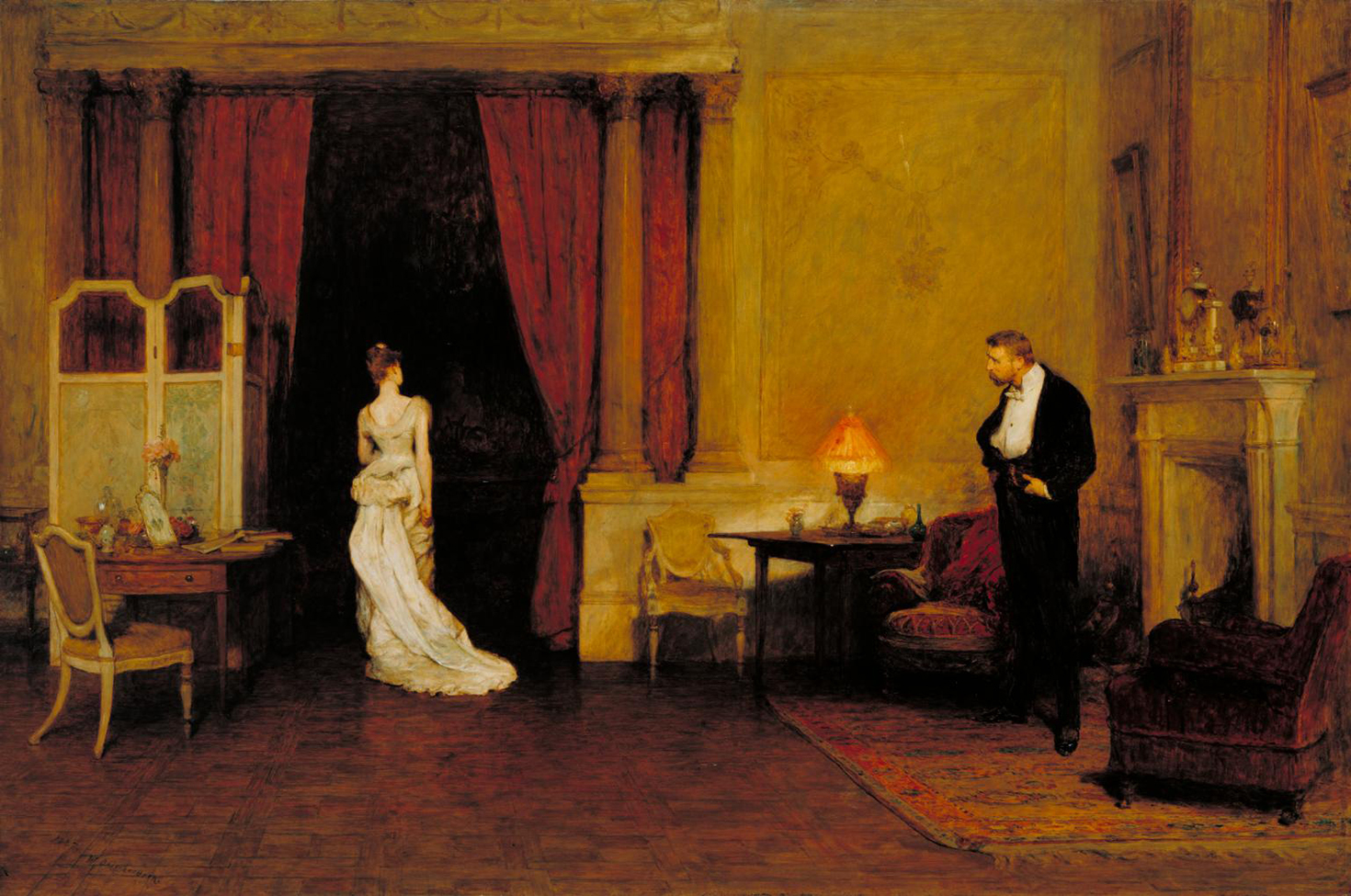

The First Cloud, by Sir William Quiller Orchardson, 1887. Photograph © Tate (CC-BY-NC-ND 3.0).

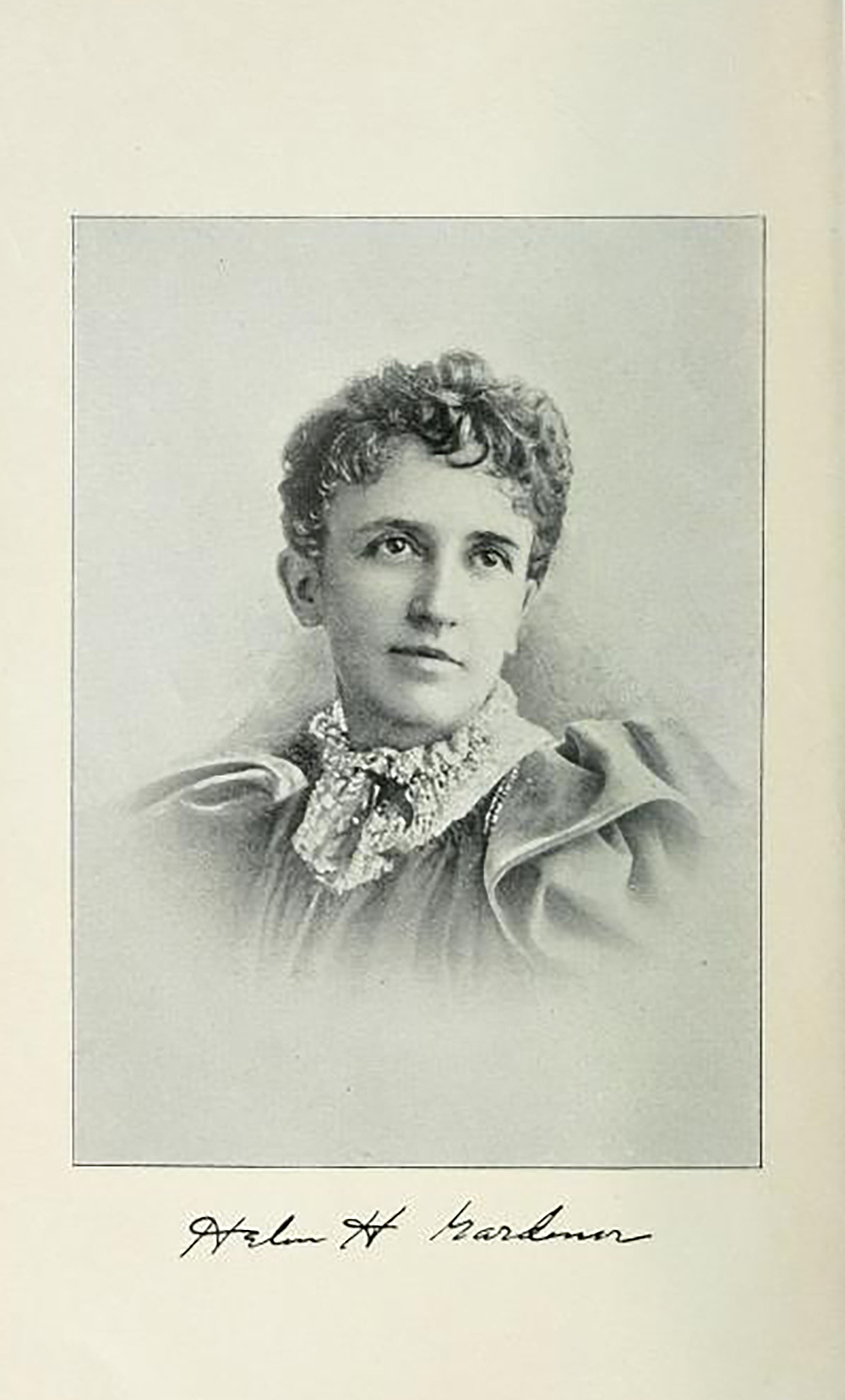

Kimberly A. Hamlin is an NEH Public Scholar; an associate professor of history at Miami University, Ohio; and a regular contributor to the Washington Post. She is the author of From Eve to Evolution: Darwin, Science and Women’s Rights in Gilded Age America. Her new book, Free Thinker, is a biography of Helen Hamilton Gardener. Hamlin introduces a classic essay by Gardener below.

In 1893 Helen Hamilton Gardener was one of the best-known women in the United States. She gave more speeches than any other American woman at the World’s Fair in Chicago that summer, where the New York Sun reported that, next to Susan B. Anthony, she created “the profoundest sensation.” What made Gardener so appealing was her combination of feminine charm and intellectual boldness. From the moment she entered public life on the free-thought lecture circuit in January 1884, Gardener prided herself on saying the things other women thought but dared not voice. First, she argued that “every injustice that has ever been fastened upon women in a Christian country has been ‘authorized by the Bible.’ ” Next, she turned her attention to the sexist science of her era. And by the time she got to Chicago in 1893, she violated not only social taboos but also anti-obscenity laws to openly critique the sexual double standard and the popular narratives that helped perpetuate it. In the early 1890s she published two novels dramatizing the common practice of grown men having sex with girls (in 1890 the age of sexual consent for girls was twelve or younger in thirty-eight states). For her efforts to raise the age of consent, Gardener became known as “The Harriet Beecher Stowe of Fallen Women.” The following essay, “The Fictions of Fiction,” appeared in her 1893 collection Facts and Fictions of Life, a compilation of Gardener’s speeches including several that she delivered at the World’s Fair in Chicago. To Gardener, the most harmful “fiction of fiction” was the idea that “woman was created for the benefit and pleasure of man, while man exists for and because of himself.”

I read—on a recent railway journey—a popular magazine. Its leading story was labeled as a “story for girls.” In it the traditional gentleman of reduced fortunes continued to still further deplete the family resources by speculation, and the three daughters who figure in most such stories went through the regular paces, so to speak.

One taught music, one painted well and sold her bits of canvas for ten dollars each, but the third girl had no talent except that of a cheerful temperament and the ability to drape curtains and arrange furniture attractively. These girls talked over the fact that they were now reduced to their last ten dollars and the pantry was empty, father ill, and mother—not counted. They joked a little, wept a few tears, and prayed devoutly. Then the talentless one received an invitation in the very nick of time to visit the richest lady in town (a cripple with a grand house). She went, she saw, and, of course, she conquered. She earned money by giving artistic touches to the houses of all the rich people in town, and eight months later married the nephew of the opulent cripple. No more mention is made of the empty pantry, the sick father, or the two talented girls whose labor did not previously keep the wolf from the door. But it is only fair to suppose that the new husband was to be henceforth the head of the entire establishment—surely a warning to most young men contemplating matrimony under such trying circumstances.

All is supposed to move on well, however, and every hapless girl who reads such a story is led to believe that she is the household fairy who will meet the prince and somehow (not stated) redeem her father’s family from want and despair. For it is the object of such stories to convey the impression that everything is quite comfortable and settled after the wedding. The young girl who reads these stories looks out upon life through the absurd spectacle thus furnished her. She sees nothing as it is. Such little plans as she can make are based upon wholly incorrect data. Her whole existence is unconsciously made to bend to the idea of matrimony as a means of salvation for herself and such persons as may be in any way objects of care to her.

What are commonly known as “safe stories for girls” are made up of just such rubbish, which if it were only rubbish might be tolerated. But the harm all this sort of thing does can hardly be estimated. I do not now refer to the harm of a more vicious sort that is sometimes spoken of as the result of story reading. I am not considering the deliberately scheming nor the consciously self-sacrificing girl who struts her day on the stage and in fiction marries to save the farm or her father or anyone else. I am thinking of the everyday girl, who is simply led to see life exactly as it is likely not to be, and is therefore disarmed at the outset. She is filled with all sorts of dreamy ideas of rescue by prayer or by means of some suddenly developed—previously undreamed-of—rich relation or lover or, I had almost said, fairy. And why not? Literature used to bristle with these intangible aids to the helpless or stranded author. The name is changed now, it is true, but the fairy business goes bravely on at the old stand, and the young are fed with views of life, and of what they will be called upon to meet, which are nonetheless harmful and visionary because of the changed nomenclature.

A gentleman of middle age said to me not long ago:

I grew up with the idea that people were like those I met in books. I went out into life with that belief. I measured myself by those standards, and I have spent much time in my later years readjusting myself to fit the facts. It placed me at a great disadvantage. I saw people and deeds as they were not—as they are never likely to be in this world—and I could not believe that my own case was not wholly exceptional. I began to look at myself as quite out of the ordinary. My experiences were such as belied my reading, and it was a very long time and after serious struggle that I discovered that it was my false standards, derived from reading popular fiction, that had deceived me and that, after all, life had to be met upon very different lines from the ones laid down by the ordinary writers of fiction. I really believe I was unfitted for life as I found it, more by the fictions of fiction than by any other one influence.

Another gentleman—a writer of renown—said to me: “We may not ‘hold the mirror up to nature’ as nature is. The critics will not have it. We must hold it up to what we are led to think nature ought to be.”

Now that would be all very well, no doubt, if the picture were labeled to fit the facts. If it were distinctly understood by the reader that in ninety-nine cases out of a hundred the outcome of real life would be wholly different, that the right man would not turn up, in the nick of time, to point out to the defenseless widow that there was a flaw in the deed. If the reader was warned that honest effort often precedes failure, that virtue and vice not only may, but do, walk hand in hand down many a lifelong path and sometimes get the boundary lines quite obliterated between them. If he understood that in life the biggest scoundrel often wears the most benign countenance and does not go about with a leer and a scowl that labels him, all might be well.

A prominent woman, an authority on social topics who is also a writer, a short time ago announced to her audience of ladies, who gave the smiling response of a thoughtless yes, that “no one ever committed a despicable act with the head erect and the chest well out.” “A dishonest man, a criminal, a mean woman,” she said, always carry themselves so-and-so!

If that were true—if it bore only the relationship of probability to truth—courts of law to determine upon questions of guilt or innocence would be quite unnecessary. A photograph and an anatomical expert would do the business. The doing of a wrong act would become impossible to a gymnast, and the graceful “bareback lady” in the circus would be farther removed from all meanness of soul than any other woman living.

Yet some such idea—stated a little less absurdly—runs through fiction, drama, and poetry.

Ferdinand Ward or Carlyle Harris would figure in orthodox fiction with “furtive eyes,” “a hunted look,” and with very hard and repellent features. Yet those who knew them well never discovered any such expressions. Jesse James would look like a ruffian and treat his old mother like a brute. But in life he was a mild, quiet, fair-appearing man who adored his mother, and was shot in the back (while tenderly wiping the dust from her picture) by a despicable wretch who was living upon his bounty at the time and accepted a bribe to murder him. Young girls do not need to be warned against “mother Frochards.” No girl of fair sense would require such warning, but the plausible, good-looking, and often nobly acting man or woman who lapses from rectitude in one path while carefully treading the straight and narrow way in all earnestness and with honest intent in others are the ones for whom the fictions of fiction leave us unprepared.

In short the people who do not exist—the villain who is consistently and invariably villainous, the woman who is an angel, the people who never make mistakes or who are able and wise enough to rectify them nobly, and all the endless brood are familiar enough. We know all of them and are prepared for them when we meet them—which we never do. But for the real people we are not prepared.

For the exigencies of life that come, for the decisions and judgments we are called upon to make, the fictions of fiction have contributed to disarm us. We are hampered. There is no precedent. We feel ourselves imposed upon. We are face-to-face, so we believe, with a condition that no one ever met before. We are dazed; we wait for the orthodox denouement. It does not come. We pray. There is no angel visitant who cools our fevered brow with gentle wings and lulls our fears with promise of help from other than human agencies—which promises are straightway fulfilled, of course, in fiction. We sit down and wait, but no rich relation dies and leaves us a legacy, nor does the prince appear and wed us. Nothing is orthodox, but we have lost much valuable time, and strength, and hope in waiting for it to be so. We have failed to adjust ourselves to life as it is. We do not measure ourselves nor others by standards that have a par value. We are discouraged and we are at sea.

A short time ago I read a story of the late war. The burden of it was that, if a soldier had been brave and loyal, he could also be depended upon to be honest. I happened to read the story while under the same roof with an old soldier who was at that time a judge on the bench. He had served faithfully while in the army; he was brave and he, no doubt, deserved the honorable discharge he received, and yet while he sat on the bench, he applied for a pension on the ground of incurable disease “contracted in active service.” While those papers were being investigated and one doctor was examining him for his pension, he also applied and was examined for life insurance as a perfectly sound man and healthy risk, and he got both.

The fact is human nature is very much mixed. Good and bad is not divided by classes but is pretty well distributed in the same individual. Weakness and strength, wisdom and ignorance, impulse and reason, play their part in the same life with all the other attributes, passions, and conditions, and the literature which makes any individual the personification of good or of evil leads astray its confiding readers. Woman has been represented in literature as emotion culminating in self-sacrifice and matrimony. That was all. And even unto this day many persons can conceive of her in no other light. The idea has always been productive of infinite misery to woman whose whole book of life was read by these pages only, as well as to man who had carefully to spell out the other pages in the characters of wife or daughter when it was too late for him to learn new lessons or to develop a taste for an unknown language.

Man has been known as pure reason touched with chivalry and devotion or else as a dangerous animal who preys upon his kind. There may be—in some other life or world—representatives of both of these classes, but they are not the men with whom we live and, therefore, whose acquaintance it is desirable we should make as early as possible.

That a large family is a crown of glory to the parents and an inestimable boon to the state is an idea running through literature. Is it a fact or is it one of the fictions of fiction which it were well to stimulate and galvanize into life less persistently? What is the answer from reform schools and penal institutions, filled by ignorance and passion held in bondage by poverty; from cemeteries where mothers and babies of the poor and ill-nurtured are strewn like leaves; from the homes of the educated and well-to-do where small families are the rule (large ones the deplored exception)? What is the logical reply in countries whose sociological students sigh over the struggle for existence and a scarcity of supplies: “overpopulation” and desperate emigration? Misery and vice bearing strict proportion to density of population and poverty surely offer a hint that at least one of the fictions of fiction has gone far to do a serious injury to man.

But the fiction of fictions which has done more real harm to the human race than any other, perhaps, is the one which dominates it: the idea that woman was created for the benefit and pleasure of man, while man exists for and because of himself.

Fiction has utilized even her hours of leisure and amusement to sap the self-respect of womanhood while it helped very greatly to brutalize and lower man by keeping—in this insidious form—the thought ever before him that woman is a function only and not a person, and that even in this limited sphere she is and should be proud to be man’s subject. “He for God only, she for God in him.”

It is true that since the advent of women writers fiction has shown a tendency to modify, to a limited extent, this previously universal dictum, but the thought still dominates literature greatly to the detriment of morals and of the dignity of both men and women.

“The woman who has no history is the woman to be envied,” says literature, and yet people do not envy her any more than they do the man of like inconspicuous position. No one wishes that she might go down to history, if one may so express it, as history-less. No one points with pride to Jane Smith as his illustrious ancestor any more than if Jane had chanced to be John. To have been a Mary Somerville, or an Elizabeth Barrett Browning, or a George Eliot, most historyless women would be willing to change places even now, and as for “those who come after,” can there be a question as to which would give more pride or pleasure to man or woman, to say, “I am the son, or the brother, or the niece of Mrs. Browning,” or to say, “Jane Smith, of Amityville, is my most famous relative?”

I have my suspicions that even Mr. FitzGerald would waver in favor of Elizabeth in case both women were his cousins.1 In public, at least, he would mention Jane less frequently and with less of a touch of pride. Personally he might like her quite as well. That is aside from the question. I have no doubt that he might like John Smith as well as Shakespeare personally, too, and John may have led a happier life than William, but is a man with no history to be envied for that reason? The application is obvious.

One of the most insidious fictions of fiction—which it seems to me is harmful—is the theory that the good are so because they resist temptation, while the bad are vicious because they yield easily.

Leaving out heredity and its tremendous power, it is likely that you would have yielded under as strong pressure as it took to carry your neighbor down. I say as strong pressure—not the same pressure—for your tastes not being the same, your temptations will take different forms.2

If you had been born of similar parents and on Cherry Hill, if you had been one of a family of ten, if you had been stunted in mind and in body by want of nourishment, if you had been given little or no education, if you had helped to get bread for the family almost from the time you could remember—your record in the police court would not differ very greatly from that of those about you. In nine cases out of ten you would be where you sent that convict last year. Your pretty daughter would be the associate of toughs. She might be pure—in the sense in which the word is applied to women—but she would have a mind muddy and foul with the murk and odors of a life fit only for swine. She would marry a brute who honestly believes that so soon as the words of a priest or a magistrate are said over them, she belongs to him to abuse if he sees fit, to impose upon, lie to, or to let down into the valley of death for his pleasure whenever he sees fit, and quite without regard to her opinions or desires in the matter. She would be an old and broken woman at thirty, ugly, misshapen, and hopeless, with hungry-faced children about her, whose next meal would be a piece of bread, whose next word would be too foul to repeat, whose next act would disgrace a wolf.

In turn they would perpetuate their kind in much the same fashion, and some of your grandchildren would be in the poorhouse, some in prison, some in houses of ill repute, and perchance some doing honest work—sweeping the streets or making shirts for forty cents a dozen for the patrons of a literature that goes on promoting the theory that the chief duty of the poor is to irresponsibly bring more children into the world to work for them as cheaply as possible. To the end that they may restrict their own families to smaller limits and—by means of cheaper labor caused largely by overpopulation from below—clothe their loved ones in purple and build untaxed temples of worship, where poverty and crime is taught to believe in that other fiction of fictions—the “providence” that places us where we deserve to be and where a loving God wishes us to be content.

Indeed, this supernatural finger in literature has gone farther, perhaps, to place and keep fiction where it is, as a misleading picture of life and reality, than has any other influence. It has dominated talent and either starved or broken the pen of genius. “Oh, if I might be allowed to draw a man as he is!” exclaims Thackeray, as he leaves the office of his publisher, with downcast eyes and bowed head. He goes home and “cuts out most of his facts,” and returns the manuscript, which is acceptable now because it is not true to life!

Because it is now fiction based upon other fiction and has eliminated from it the elements of probability which might have been educative or stimulating or prophetic. Now, Thackeray was not a man who would have mistaken preachments for novels if he had been left to his own judgment; neither would he have painted vice with a hand that made it attractive, but he chafed under the dictum that he must not hold the mirror up to the face of nature but must adjust it carefully so as to reflect a steel engraving of a watercolor from a copy of the “old masters.”

It might be well if silver dollars grew on trees and if each person could step out and gather them at his pleasure. Since they do not, what good purpose could it serve if fiction were to iterate and reiterate that such is the case, until people believed that it was their trees which were at fault and not their fiction?

It might be a good idea, too, if babies were born with a knowledge of Latin and mathematics, but to convince young people that such is the case and that they are pitiful exceptions to a general rule is to place them at a humiliating disadvantage from the outset.

It is one of the most firmly rooted of these fictions of fiction that such tales as I have mentioned above are “good reading—safe, clean literature” for girls. Nothing could be farther from the facts. Indeed, the outcry about girls not being allowed to read this or that, because it deals with some topic “unfit” for the girls’ ears, is another fiction of fiction which robs the girl of her most important armor—the armor of truth and the ability to adjust it to life.

A famous man once said in my presence:

The theory that to keep a girl pure you must keep her ignorant of life—of real life—is based upon a belief degrading to her and false as to facts. Some people appear to believe that if they keep girls entirely ignorant of all truth, they will necessarily become devotees of truth, and if you could succeed in finding a girl who is a perfect idiot, you would find one who is also a perfect angel.

“We are a variegated lot at best and worst,” said a lady to me the other day, when discussing the character of a man who is in the public eye. “I know a different side of his character. The side I know I like. The side the public knows is so different.” But in fiction he would be all one way. He would be a scamp and know it, or he would be a saint and know that too. The fact is he is neither, and we are a variegated set at best and worst. Why not out with it in fiction and be armed and equipped for character and life as it is?

There is a school of critics who will say this is not the province of fiction. Fiction is to entertain, not to instruct. With this I do not agree—only in part. But accepting the standard for the moment, I am sure that a picture of life as it is is far more entertaining than is that shadowy and vague photograph of ghosts taken by moonlight, which “safe stories for the young” generally present.

But to enumerate the fictions of fiction would be to undertake an arduous task; to comment upon them all would be impossible.

How much remorse—how many heartbreaks—have been caused by the one of these which may be indicated briefly in a sentence thus: “Stolen pleasures are always the sweetest.”

“She sullied his honor,” “He avenged his sullied honor,” and all the brood of ideas that follows in this line have built up theories and caused more useless bloodshed and sorrow than most others. No wife can stain the honor of her husband. He, only, can do that, and it is interesting to note the fact that he who struts through fiction with a broken heart and a drawn sword “avenging” said honor (in the sense in which the word is used) seldom had any to avenge, having quite effectively divested himself of it before his wife had the chance.

“She begged him to make an honest woman of her.” What fiction of fiction (and, alas, of law) could be more degrading to womanhood—and hence to humanity—than the thought here presented? The whole chain of ideas linked here is vicious and vicious only. Why sustain the fiction that a woman can be elevated by making her the permanent victim of one who has already abused her confidence, and now holds himself—because of his own perfidy—as in a position to confer honor upon his victim? He who is not possessed of honor cannot confer it upon another. “The purity of family life” is another fiction of fiction which never did and never can exist, while based upon a double standard of morals. That there ever was or ever will be a “union of souls” in a family where a double standard holds sway, or that women are truthful or frank with men upon whom they are dependent, are fictions which it were time to face and controvert with facts. Dependence and frankness never coexisted in this world in an adult brain—whether it were the dependence of the serf or of the wife or daughter, the result is ever the same. The elements of character which tend to self-respect and hence to open and truthful natures are not possible in a dependent or in a social or political inferior. Do the peasants tell the lord exactly what they think of him, or do they tell him what they know he wishes them to think?

Did the black men, while yet slaves, give to the master their own unbiased opinion of the institution of slavery? Not with any degree of frequency. The application is obvious.

Another of the fictions of fiction upon which the vicious build, and which has disarmed thousands before the battle, is the insistency with which the idea is presented that a man (or woman) who is honestly and truly and conscientiously religious is therefore necessarily moral or honorable: that he is a hypocrite in his religion if he is a knave in his life. Observation and history and logic are all against the theory. Some of the most exaltedly religious men have been the most wholly immoral. It was honest religion that burned Servetus and Bruno. They were not hypocrites who hunted witches. It is not hypocrisy that draws its skirts aside from a “fallen” sister and immorally marries her companion in illicit love to purity and innocence. Do you know any religious father (or many mothers) in this world who would refuse to allow their son, whom they know to be of bad character, to marry a girl who is as pure and spotless and suspicionless as a flower? “She will reform him,” they say. “It will be good for him to marry such a girl.” And how will it be for her? Does the religious man or woman not take this view of morals? Has right and wrong sex? Is honor and truthfulness toward others limited in application? Have you a right to deceive certain people for the pleasure or benefit of other people? If so, where is the boundary line? Would the girl marry you or your son if she knew the exact truth, if she were to see with her own and not with your eyes all of your life? Would you be willing to take her with you, or for her to go unknown to you, through all the experiences of your past and present? No? Would you be willing to marry her if she had exactly your record? No? You truly believe then that she is worthy of less than you are? Honor does not demand as much of you for her as it does of her for you? You would think she had a right. You would not resent it if her life had been exactly what yours was and is and if she had deceived you? Is that which is coarse or low for women not so for men? Why is it that men will not submit to, if it comes from women, that which they impose upon women whom they “adore” and “truly respect?”

Would women accept this sort of respect and adoration if they were not dependents? Does literature throw a true or a fictitious light on such questions as these?

To whose advantage is it to sustain such fictitious standard of morals, of justice, of love, of right, of manliness, of honor, of womanly dignity and worth? To whose advantage is it to teach by all the arts of fiction that contentment with one’s lot—whatever the lot may be—is a virtue? Yet it is one of the fictions of fiction that the contented man or woman is the admirable person. All progress proves the contrary. To whose advantage is it to insist that virtue is always rewarded and vice punished? We know it is not true. Is it not bad enough to have been virtuous and still have failed, without having also the stigma which this failure implies under such a code? We all know that vicious success is common, that often vice and success are partners for life and that in death they are not divided, that the wicked flourish like a green bay tree. Why blink it in fiction? Why add suspicion to failure and misfortune, and gloss success with the added glory that it is necessarily the result of virtue? To those who know how false the theory is, it is a bad lesson—to those who do not know it, it is a disarmament against imposition.

Some of the fictions of fiction have their droll side in their naive contradictions of each other. These examples occur to me:

“Women are timid and secretive.”

“They can’t keep a secret.”

“They are the custodians of virtue.”

“They are the ‘frailer’ sex.”

“Frailty, thy name is woman.”

“With the passionate purity of woman.”

“Abstract justice is an attribute of the masculine mind.”

“Man’s inhumanity to man makes countless thousands mourn.”

“No class was ever able to be just to—to do justly by another class—hence the need of popular representation.”

“Women should take no part in politics.”

“Women are harder upon women than men are.”

“He disgraced his honored name by actually marrying his paramour.”

“We are happy if we are good.”

“He was one of the best and therefore one of the saddest of men.”

But why multiply examples. Many—and different ones—will occur to every thinking mind, while illustrations of the particular fictions of fiction, which have gone farthest to cripple you or your neighbor, will present themselves without more suggestions.

1 FitzGerald “thanked God” when Mrs. Browning died. See reply by Robert Browning in Athenaeum. ↩

2 “Our lives progress on the lines of least resistance.”—Van Der Warker, MD ↩

Kimberly A. Hamlin’s Free Thinker: Sex, Suffrage, and the Extraordinary Life of Helen Hamilton Gardener is out now from W.W. Norton.