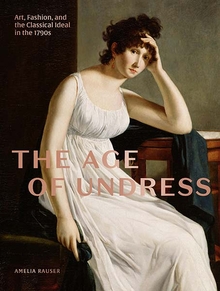

Portrait of a Young Woman, attributed to Jean Antoine Laurent, c. 1795. The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Gift of Mrs. Louis V. Bell, in memory of her husband, 1925.

A charming miniature attributed to Jean-Antoine Laurent, dated c. 1795, depicts a blond woman in a garden, wearing a simple neoclassical dress with a drawstring neckline and short sleeves. With a straw hat slung over her elbow, she presents herself as natural, authentic, and at ease. But this portrait represents her as not just a fashionable woman but as a fashionable white woman. The blond wig and madras-cloth sash were just two of many elements of neoclassical dress that specifically articulated the wearer’s racialized whiteness.

Blondness was a hair color associated with fair-skinned people, and pallor was already a marked characteristic in contemporary beauties. Blond wigs were a passionate fad in Paris immediately post-Thermidor, when fashion was resurgent after the repressions of the Terror. Such wigs were expensive since blond hair was scarce, and rumors flew that the new plethora of wigs was due to the abundant hair salvaged from the severed heads of guillotine victims. The fashion for blondness was likely connected to its long associations of youthfulness and eroticism; it also represented an artificially “natural” way to wear a light head, after powdered coiffures had become discredited by their association with the old regime.

The “whiteness” of blond hair might otherwise be unremarkable, except that it is paired, in Laurent’s miniature and elsewhere, with plaid madras cloth. The portrait includes two types of madras: a red and green check is used to sash the sitter’s waist, while a blue shawl with a striped border forms her backdrop. Madras cloth, still a part of traditional dress in the West Indies today, was used as slave currency. Woven in south India, the cloth was imported to England, where it was banned from wide sale by laws designed to protect the domestic textile industry. It was instead auctioned off to slave traders who used it to barter for enslaved people in West Africa and to clothe them in the Caribbean, one of the few markets within the British and French empires where it could be legally sold.

Neoclassicism’s pristinely white, smooth, and coherent bodies helped assuage the anxiety of abjection. The abject, in psychoanalytic theory, is the part of the self that must be disavowed and distanced, because it threatens the necessary fiction of a whole and cohesive subjectivity. It helps draw a bright borderline between “I” and “not I,” but as such it can never be permanently excluded, for it is always needed to define the self, in a structure of legitimation and subjectification. For example, heterosexuality cannot exist without the creation of an abject other, homosexuality, to constitute itself; whiteness requires blackness. Even as it is continually suppressed and disavowed, then, the abject is also continually represented, even reconstituted.

The abjection of the enslaved black body and the plantation culture it inhabited stalked neoclassical dress, which could not escape the material traces of its manufacture. Wool was not only widely produced in Europe but also had centuries of nationalistic meaning attached to it in Great Britain, while silk had long-standing national craft traditions in both England and France. By contrast, cotton muslin was a modern and imperial textile, the product of global networks and industrial innovation. Cotton fiber was grown in India, the West Indies, Asia Minor, Brazil, and parts of Africa. Indian-made fine muslins and printed calicoes began to enter the European market in the seventeenth century and were impossible for European producers to rival. Both Britain and France banned such imports in the early eighteenth century in order to protect their domestic textile industries, although these regulations were flouted to varying degrees. It was not until the 1770s that several key inventions changed the scale and quality of cotton spinning and weaving in Europe, allowing them to approach the quality of Indian textiles and inaugurating the Industrial Revolution. Cotton also played a vital role in the eighteenth-century slave trade. Finished cotton cloth was a desirable commodity in exchange for slaves in West Africa and found a ready local market in the West Indies. In turn, the enslaved were used not only for the much larger and more established sugar industry but also for the production of raw cotton that would then be exported to the emerging factories in Liverpool and Manchester. This triangular trade accelerated in the 1780s, as a previously small cotton textile industry struggled to meet growing global demand and the price for raw cotton rose sharply. The Ottoman Empire could not increase production sufficiently, despite dragooning thousands of Greek laborers to work on cotton farms; India’s rich harvest was protected by the East India Company for the use of their skilled Indian weavers. West Indian planters were the logical focus: they controlled suitable land and had long experience producing crops with enslaved labor.

As West Indian planters stepped in to fill the growing demand for raw cotton, exports quadrupled between 1781 and 1791. This growth was fueled by the import of thousands of African slaves—during the height of the cotton boom, nearly thirty thousand slaves per year to Saint-Domingue (present-day Haiti) alone. Indeed, by the 1780s, the majority of cotton sold in markets around the world was produced by African slaves. Thus, the desire for cotton not only fueled the key innovations of the Industrial Revolution but also ingrained slavery in the emerging system of modern global capitalism. The same white muslin that glossed some bodies as natural and classical, whole and unfragmented, caused other bodies to be enslaved and endangered.

Although neoclassicism was the style associated with revolution in France and Enlightenment and liberal values elsewhere, neoclassical dress’ associations with slave culture were simultaneously openly cultivated. Several of the women most famous for wearing extreme versions of neoclassical dress in France—the so-called Merveilleuses—were themselves Creoles from the West Indies. These included Fortunée Hamelin, born to sugar planters in Saint-Domingue, and Joséphine de Beauharnais, future wife of Napoleon, raised on a sugar plantation in Martinique.

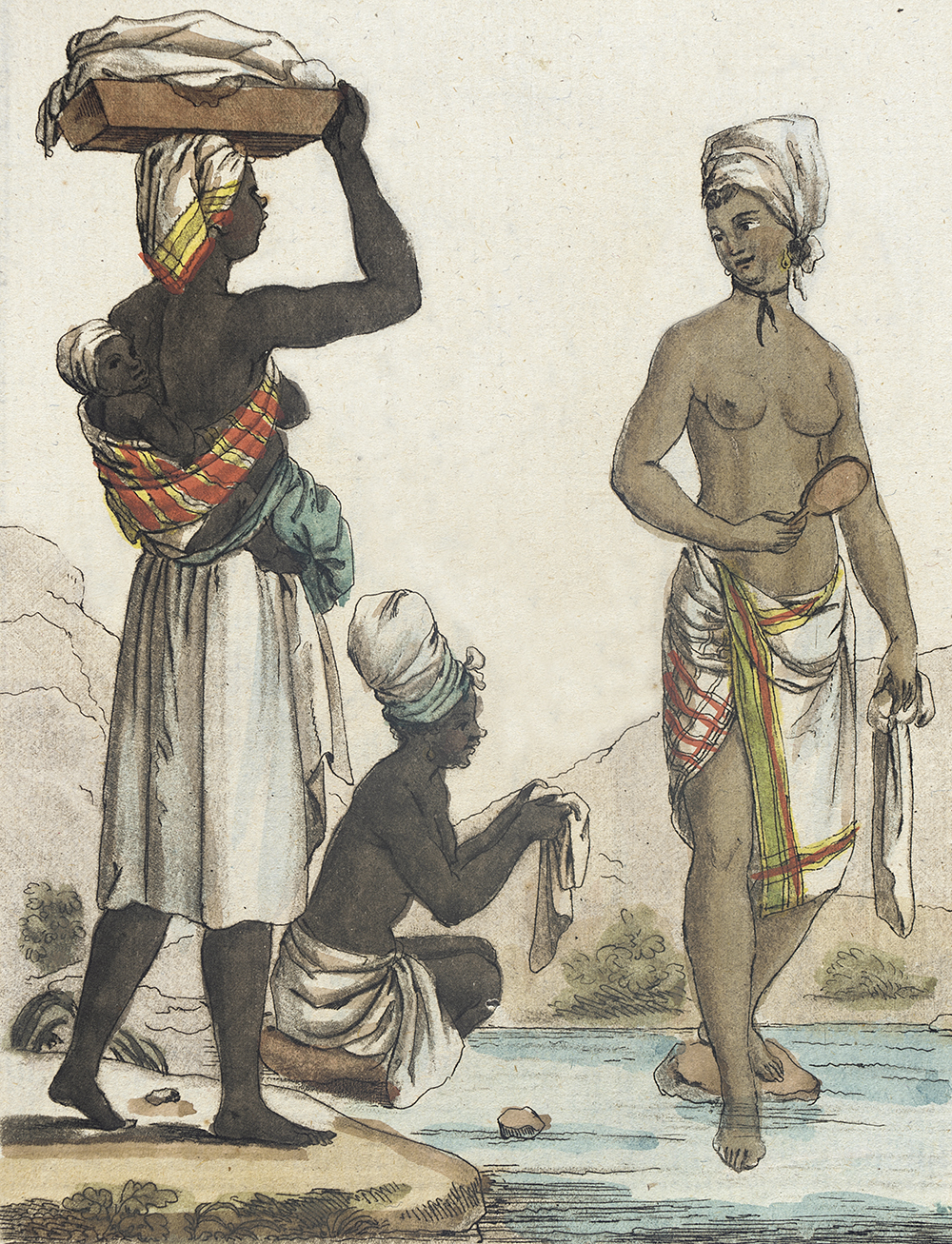

In fact, the simple round gown of white muslin was itself a West Indian invention, well documented in the paintings by Agostino Brunias of Caribbean life. The habit of caring for the textile by frequent washing with a “blueing” agent like indigo to accentuate its whiteness was also a West Indian practice. Indeed, the distinctive brilliance of white cotton blued and bleached in Saint-Domingue caught the eye of Marie Antoinette in 1782 and helped to inaugurate the fashion for the robe en chemise.

Gold hoops had long been connected with black bodies and New World marine discovery. By the eighteenth century they were associated with Creole culture, both enslaved and free, and were taken up by white women as fashionable accessories in the 1790s.

The headwrap was another distinctively West Indian garment that became absorbed into neoclassical fashion. First mandated by sumptuary laws as a way to mark the free colored woman, the headwrap was appropriated by women of all colors and classes in the West Indies and worn in a variety of forms and folds, both in madras plaid and plain muslin. As cropped curls and natural hair supplanted the frizzed, padded, and powdered headdresses of the 1780s, turbans and headwraps were widely adopted by fashionable European women in the 1790s.

But the most distinctive element of slave-inspired neoclassical fashion was madras. A 1795 illustration in the London-based Heideloff’s Gallery of Fashion shows a woman wearing a madras handkerchief as a fichu, while an 1801 plate from Paris-based Journal des dames et des modes depicts a woman in a dress made entirely of madras cloth. White women also wore madras as headwraps.

Clearly these sartorial gestures—the muslin round gown, the hoop earrings, the madras cloth, the headwrap—added up to a deliberate reference to the visual and material culture of the West Indies. This cultural appropriation is in many ways a familiar story: a mainstream culture borrows symbols from a marginalized culture to enjoy the edgy cool of its significations without the consequences of its lived reality. But what exactly did Creole culture signify to Europeans in the 1790s?

The term Creole was itself equivocal. Some used it to refer to the white plantation owners alone, while others intended the term to describe the entire multiracial mix of inhabitants of the West Indies. White Creole ladies were admired for a chic that paralleled that of consumptives in its sickly glamour; they were especially pale and gothically beautiful, with a listlessness caused by the hot climate and their austere diet. Jamaican planter Bryan Edwards wrote in 1801:

In their diet, the Creole women are, I think, abstemious even to a fault. Simple water, or lemonade, in which they indulge, and vegetable mess at noon, seasoned with cayenne pepper, constitutes their principal repast. The effect of this mode of life, in a hot or oppressive atmosphere, is a lax fiber, and a complexion in which the lily predominates rather than the rose. To a stranger newly arrived, the ladies appear as just risen from the bed of sickness. Their voice is soft and spiritless, and every step betrays languor and lassitude…they have, in general, the finest eyes in the world; large, languishing, and expressive.

The Creole woman’s desirable slightness and pallid beauty were accentuated by contrast with the black bodies that surrounded her. But Creole women also had a reputation for lustiness; as a saying went: “Creole misses, when scarcely ten / Cock their eyes and long for men.” J.B. Moreton attributed the immodest hedonism of white Creole women to their frequent fraternization with black and brown people:

If you surprise them [at home], as I have often done, you will be convinced of the truth of this assertion, that Ovid, with all his metamorphoses, could not match such transformations: instead of the well-shaped, mild, angelic-looking creature you beheld abroad, you will find, perhaps, a clumsy, greasy tomboy, or a paper-faced skeleton, romping, or stretching and lolling, from sofa to sofa, in a dirty confused hall, or piazza, with a parcel of black wenches, learning and singing obscene and filthy songs, and dancing to the tunes.

In addition, the women’s own mutability and shallowness inflamed their lust:

Their little hearts are a sort of tinder, that catch fire from every spark who flatters their vanity, and whispers them soft nonsense: they are pliable as wax, and melt like butter; and though naturally delicate in their texture, they are fondest of strong, stout-backed men.

Moreton’s account unmasked the Creole as a sham. Although she may appear like a properly “mild” English girl, with her companion “black wenches” she is greasy, romping and singing obscene songs in a “dirty confused hall.” Everything about her is unstable and unfixed; she is a “paper-faced skeleton” whose heart catches fire like tinder, is as pliable as wax, and melts like butter.

Excerpted from The Age of Undress: Art, Fashion, and the Classical Ideal in the 1790s by Amelia Rauser, just published by Yale University Press. Copyright © 2020 by Amelia Rauser. Reprinted by permission of Yale University Press.