When the Day’s Work is Done, by Henry Peach Robinson, 1877. Princeton University Art Museum, museum purchase.

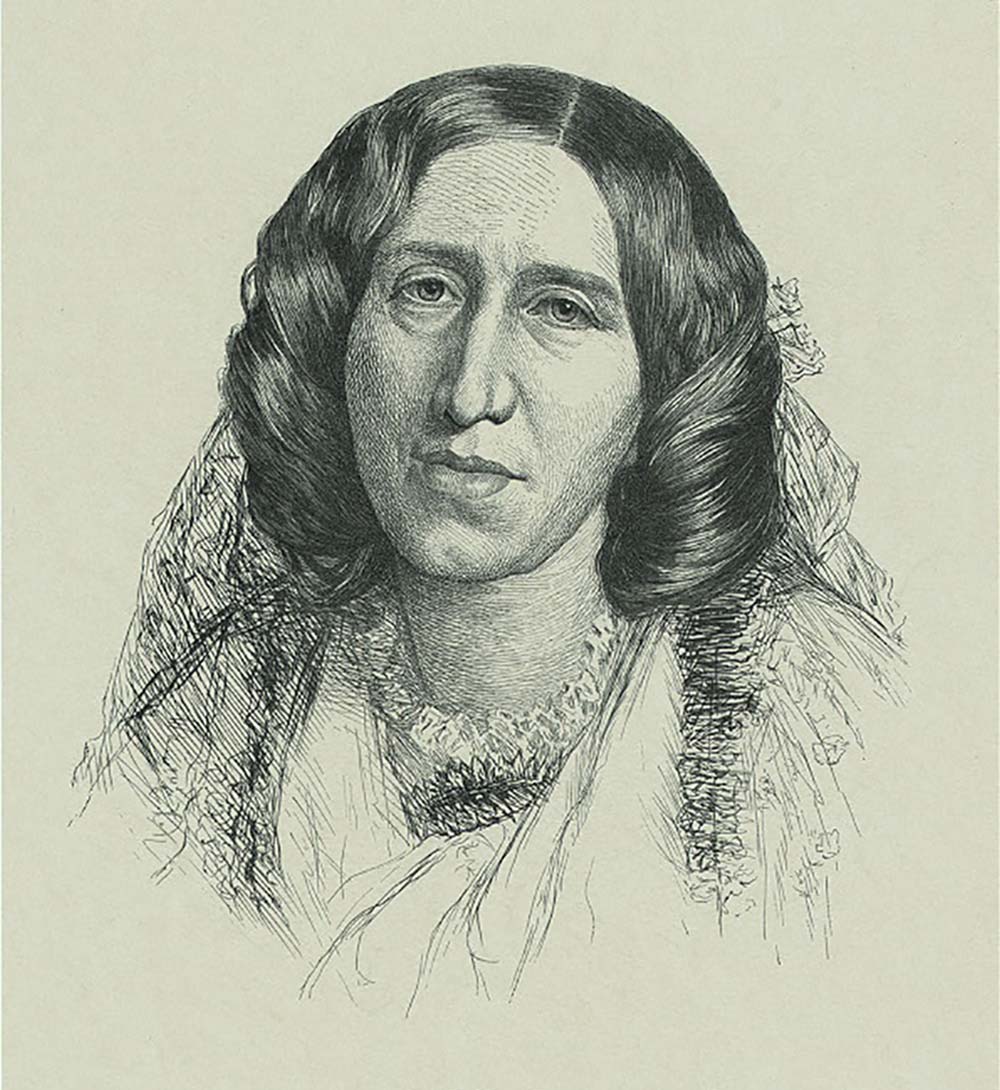

During the 1870s George Eliot’s thoughts often turned to the question of biography—some lasting portrait of herself that would be forever associated with her work. People were inevitably curious about her. She found this troubling. One shard of personal experience in Daniel Deronda is Gwendolen’s ambivalence about being looked at: she craves attention and admiration but finds herself painfully judged and controlled by other people’s eyes. Eliot shirked inquiries about the details of her life, had a “horror of being interviewed and written about.” Although it was many years since the connection between George Eliot and the scandalous “Mrs. Lewes” had been kept secret, the fear that judgements about her life might somehow contaminate her authorship still lingered. Indeed, this worry became more acute: now it was not the sales of her books that were at stake, but her enduring reputation as an artist. She had once feared she could not write her books; now that they were written and acclaimed, she was afraid of “spoiling” them.

As she and George Henry Lewes devoured biographies of great writers—Blake, Scott, Wordsworth, Keats, Byron—they could not help thinking about the biography of George Eliot. This prospect came into sharper focus after the death of Dickens, a writer of their own generation whom Lewes had known well. A three-volume Life of Charles Dickens soon appeared, written by his friend John Forster, prompting Lewes to publish his own assessment of Dickens in the Fortnightly Review. Without mentioning George Eliot, Lewes argued that Dickens’ novels lacked the intellectual power and philosophical insight that distinguished his wife’s writing: “The world of thought and passion lay beyond his horizon…I do not suppose a single thoughtful remark on life or character could be found throughout the twenty volumes…He never seems interested in general relations of things.” Dickens was not even well-read. Having been to his house and examined his unimpressive bookshelves, Lewes could pronounce him “completely outside philosophy, science, and the higher literature.” Dickens was merely a popular author, his vivid imagination perfectly suited to a mass readership “occupied with sensations rather than ideas.” More “cultivated minds,” of course, perceived the “pervading commonness” of books that were “wholly without glimpses of the nobler life.” Between the lines, Lewes was instructing the critics on how to assess George Eliot’s genius.

For Eliot, Forster’s Life of Charles Dickens conjured unsettling visions of some future biographer prying into her personal affairs, and diverting attention from her art. “Is it not odious that as soon as a man is dead his desk is raked, and every insignificant memorandum which he never meant for the public, is printed for the gossiping amusement of people too idle to re-read his books?” she wrote to her publisher, John Blackwood. This “fashion” for literary biography was “a disgrace to us all. It is something like the uncovering of the dead Byron’s club foot.” The intense ambition that had churned within her as a girl was still there, shifting its shape, generating fresh anxieties. Perhaps this ambition was Eliot’s club foot—a shameful and unseemly secret, as incongruous in an aging woman as a deformed limb in a virile young poet. Her gentle demeanor, her thoughtfulness for others, her reticence about herself, and the idea of artistic purity all helped to cover it up.

When an admiring reader of Daniel Deronda wanted to publish her reply to one of his letters in the Jewish Chronicle, she spelled out her fear: “Any influence I have as an author would be injured by the presentation of myself in print through any other medium than that of my books.” And when her friend Elma Stuart asked permission to mention her in an autobiographical essay, she replied: “My writings are public property: it is only myself apart from my writings that I hold private and claim a veto about as a topic.” In other words, Elma could refer only to George Eliot’s writing, and not to their friendship. Eliot refused to read what Elma wrote about her until the essay was published—and she especially insisted that Lewes should not be involved either. While she tended to retreat from public view, he was more inclined to curate her image.

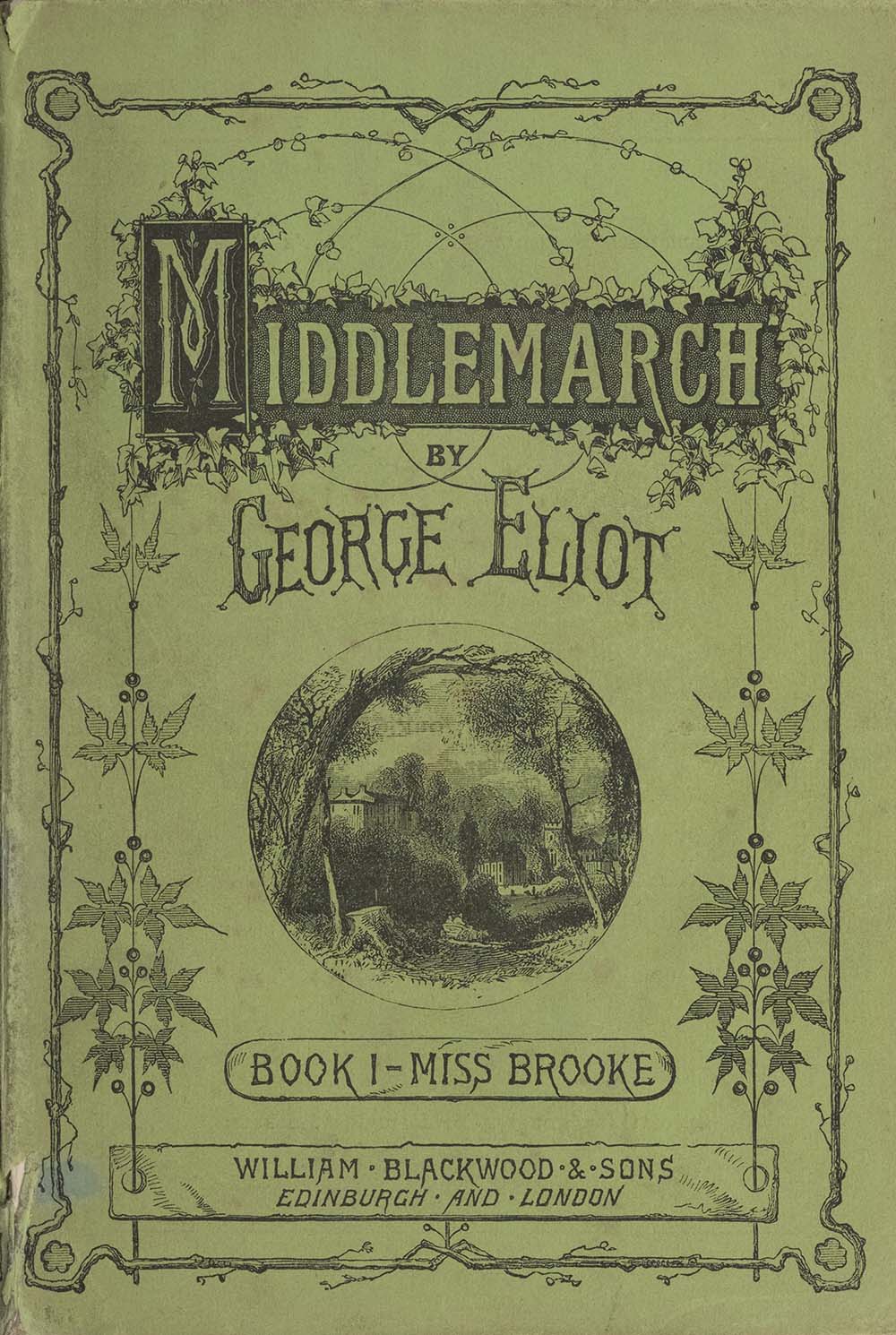

As the Leweses felt their lives fading, George Eliot was becoming immortal. “Hardly anything could have happened to me which I could regard as a greater blessing than this growth of my spiritual existence while my bodily existence is decaying,” she wrote in her journal after Middlemarch was published. Daniel Deronda crowned an artistic legacy that critics and scholars would take more than a century to reckon with.

She worried that if she wrote more, or revealed her personal life, or tethered her “spiritual existence” as an author to any specific political cause, she might diminish George Eliot’s legacy. At times she hesitated even to state her own opinions, as if she had created something so exquisite that she dared not breathe on it. She found herself becoming “more and more timid—with less daring to adopt any formula which does not get itself clothed…in some human figure and individual experience.” Yet this reticence was not merely a symptom of anxiety about her reputation. It was also a “sign” of her moral destiny: “If I help others to see at all it must be through that medium of art.” Here Eliot seems to sense that what she ascribes to timidity, as if it were a personal quirk, could be a philosophical imperative. Her need to keep thought clothed in human form was a need to integrate intellect and emotion, ideas and experience—to inhabit and convey feeling, not simply analyze it.

On her birthday in 1870 Lewes had given her “a lock-up book for her autobiography.” Eliot contemplated writing her own life, with mixed feelings and a sense of complexity. She told her friend Emily Davies that it was “impossible for her to write an autobiography, but she wished that someone else could do it, it might be useful—or, that she could do it herself.”

That was in 1869, on the verge of writing Middlemarch; perhaps an autobiography seemed impossible just because her time and energies were needed for the next novel. Did she hope that Lewes would write it for her? No one was better qualified: his biography of Goethe was his most successful work, and of course he had privileged access to her life story. But she seemed to have some qualms about this, which made her determined to prevent Lewes from influencing Elma Stuart’s essay about her. An autobiography of George Eliot should, she believed, be edifying; it should augment the influence of her art. She could write her history “better than anyone else,” she told Davies, “because she could do it impartially, judging herself and showing how wrong she was.” It is difficult to imagine Lewes, high priest of her shrine, dwelling on her faults and mistakes.

He got into the habit of recording her daily reading in his own diary; perhaps these notes would be useful if either of them came to write her life. They began to hear that old acquaintances—John Stuart Mill, Harriet Martineau, Herbert Spencer—were writing autobiographies. Martineau’s was published posthumously in 1877, and they read it together. The book provoked Eliot’s ambivalence: she told her friend Sara Hennell that it deepened her “repugnance to autobiography, unless it can be so written as to involve neither self-glorification nor impeachment of others.” When she cringed at Martineau’s willingness to discuss reviews of her books, she was thinking about herself—wishing she had never “said a word to anybody about either compliments or injuries in relation to my own doings.” She would certainly not be writing “such things down” to be published after her death.

Eliot expressed her uncertainties about life-writing in a new semifictional, knowingly genre-bending work, neither a novel nor an autobiography. For the first time since The Lifted Veil she wrote in the first person. Her narrator, Theophrastus Such, is an uncanny mixture of features identical to and different from her own—like a photographic negative, a likeness in which certain elements are inverted. He was born in the rural Midlands to a Tory father who, like Robert Evans, was a contemporary of Scott and Wordsworth—men born around 1770, just over a hundred years previously. Theophrastus is, in other words, a child of both Romanticism and conservative Middle England. Now he lives in London, and his “consciousness is chiefly of the busy, anxious metropolitan sort.” He is bookish and an author, with a special interest in moral philosophy. He feels “a permanent longing for approbation, sympathy, and love.” Yet he is a man, lives alone, has remained a bachelor, and has failed as an author, having written only one book, which “nobody is likely to have read.” He is “not rich,” and has “no very high connections.” Perhaps he resembles the person Marian Evans might have become if she had not met Lewes.

The new work, initially titled Characters and Characteristics of Theophrastus Such, was a series of short satirical essays. They explored various aspects of authorship—research, originality, plagiarism, productivity, reputation, self-importance—as well as the intertwined themes of moral character and national character, returning to questions about Jewishness and Englishness investigated in Daniel Deronda. The first essay, “Looking Inward,” muses on the problems of autobiography, which Theophrastus finds to be fraught with the twin perils of “self-ignorance” and “self-betrayal.” He is a keen observer of the “characters” he meets—but can he give a true account of his own character? While he harbors “secrets unguessed by others,” other people can perceive secrets unguessed by him. “Is it then possible,” he asks, “to describe oneself at once faithfully and fully?” It seems not. Any autobiography, like any biography, must be incomplete, studded with secrets, and even somewhat untrue.

Theophrastus Such is named after the ancient Greek philosopher Theophrastus, Aristotle’s pupil, friend, and collaborator: together they studied ethics and metaphysics, plants and animals, logic and poetry, and stars and stones. In his most enduring work, the Characters, Theophrastus applied Aristotle’s method of close observation to social life. His humorous character sketches embody vices in human types—the Flatterer, the Complacent Man, the Surly Man, the Coward, and so on. Theophrastus’ Characters created a new genre for moral philosophy.

Rather than considering abstract definitions of right and wrong, or formulating rules and maxims, or constructing theories of utilitarianism and deontology, Theophrastus put the question of what kind of people we want to be—and what kind of people we want to be with—at the heart of ethical thinking. Eliot had followed his lead when she refused to adopt any philosophical formula that was not “clothed in some human figure and individual experience.” Through the seventeenth-century salonistes they inspired, Theophrastus’ character sketches shaped a literary tradition that she had drawn on as she experimented with fiction writing during her honeymoon months with Lewes. As George Eliot she, too, had pioneered a new genre for moral philosophy.

Eliot worked steadily on her Theophrastus essays through 1878. During the summer Lewes and Eliot took turns being unwell. “My little man is sadly out of health, racked with cramps from suppressed gout and feeling his inward economy all wrong,” Eliot told Elma at the end of June. “Madonna I grieve to say is and has been much out of sorts, but nothing serious,” Lewes reported a few days later. “I get up at six and before breakfast take a solitary ramble, which I greatly enjoy but which I can’t get Madonna to share. Instead of this, she sits up in bed and buries herself in Dante or Homer. When the weather is cooler I hope to get her into regular practice of lawn tennis, but at present except our drives in the afternoon she gets but little of the sunshine and breezes to put color into her cheeks.”

By August, Eliot was feeling better and Lewes had relapsed. Theophrastus Such was finished by November, and on November 21—the day before Eliot’s fifty-ninth birthday—Lewes summoned himself from sickness to send the manuscript to John Blackwood. That afternoon he “imprudently drove out…with his usual eagerness to get through numerous details of business,” and returned home exhausted. Doctors came and went; Lewes seemed better, then worse.

As Lewes lay in bed and Eliot sat beside him, they talked about her new book: how it should be printed, how it should be advertised. Blackwood sent a specimen page, and they looked at it together on November 28. “O how nice!” said Lewes, after examining it closely. The next day seemed like it might be his last; Lewes died at dusk the following evening.

Suddenly their double life had been transfigured into awful grief. It was never Eliot’s way to flee from suffering, and now she stayed close to its source. Grief is a mode of love; she withdrew into it and felt its pain intensely. Often sadness and fear overwhelmed her: when she was a girl she had hysterical fits, especially at night, and these returned now. She did not attend Lewes’ funeral at Highgate Cemetery. As soon as he died she resolved to “carry out his wishes” by finishing his last book. She immersed herself in his manuscript, his published work, his letters and journals. She also set up a Cambridge studentship in science in his name, endowed with £5,000, a huge sum. When she was not working on Lewes’ book she read poetry about death and loss and copied out fragments that spoke of being merged with sorrow, possessed by grief.

Excerpted from The Marriage Question: George Eliot’s Double Life by Clare Carlisle. Published by Farrar, Straus and Giroux. Copyright © 2023 by Clare Carlisle. All rights reserved.