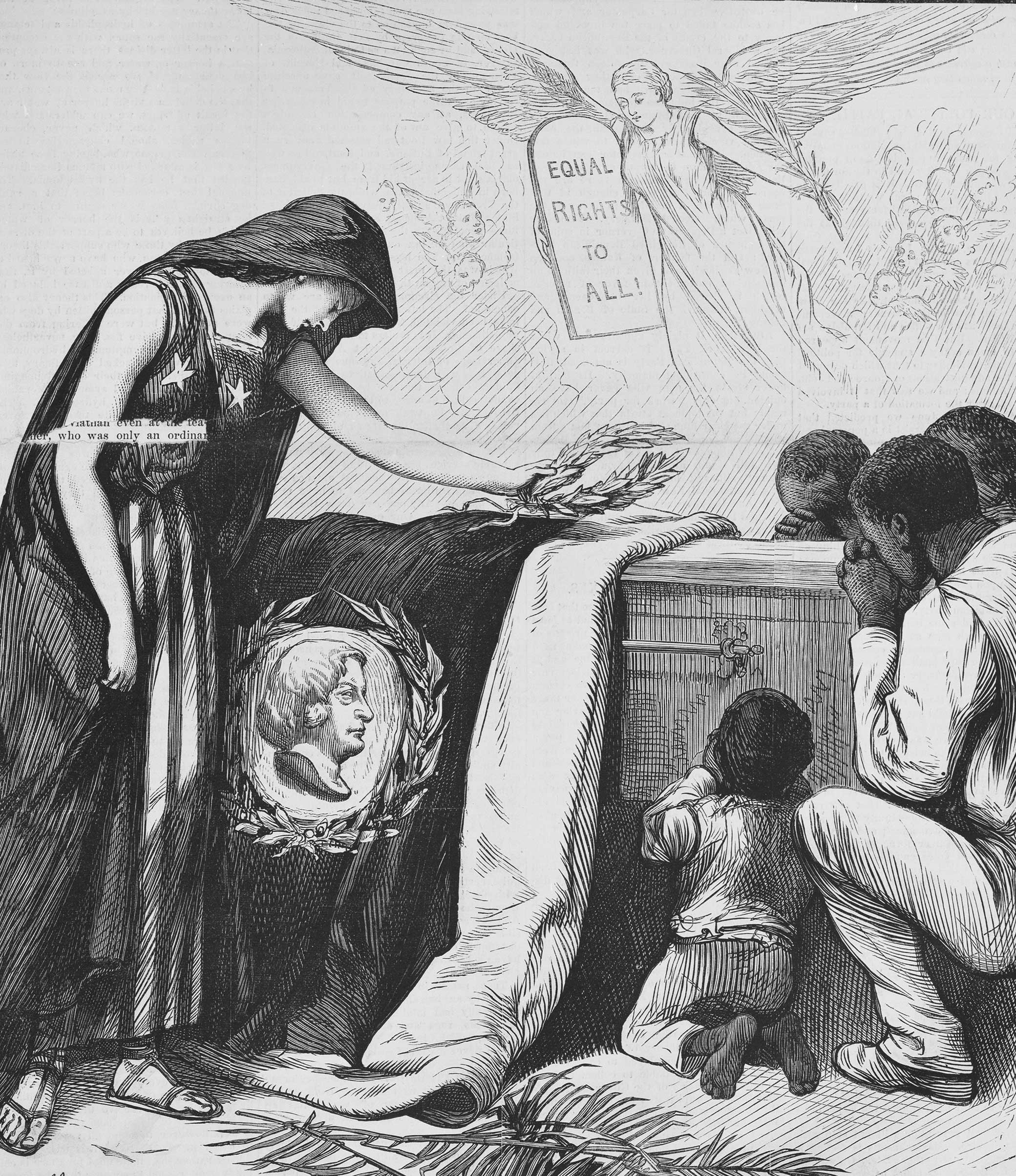

Illustration of Charles Sumner’s casket by Matt Morgan, from Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper, 1874. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

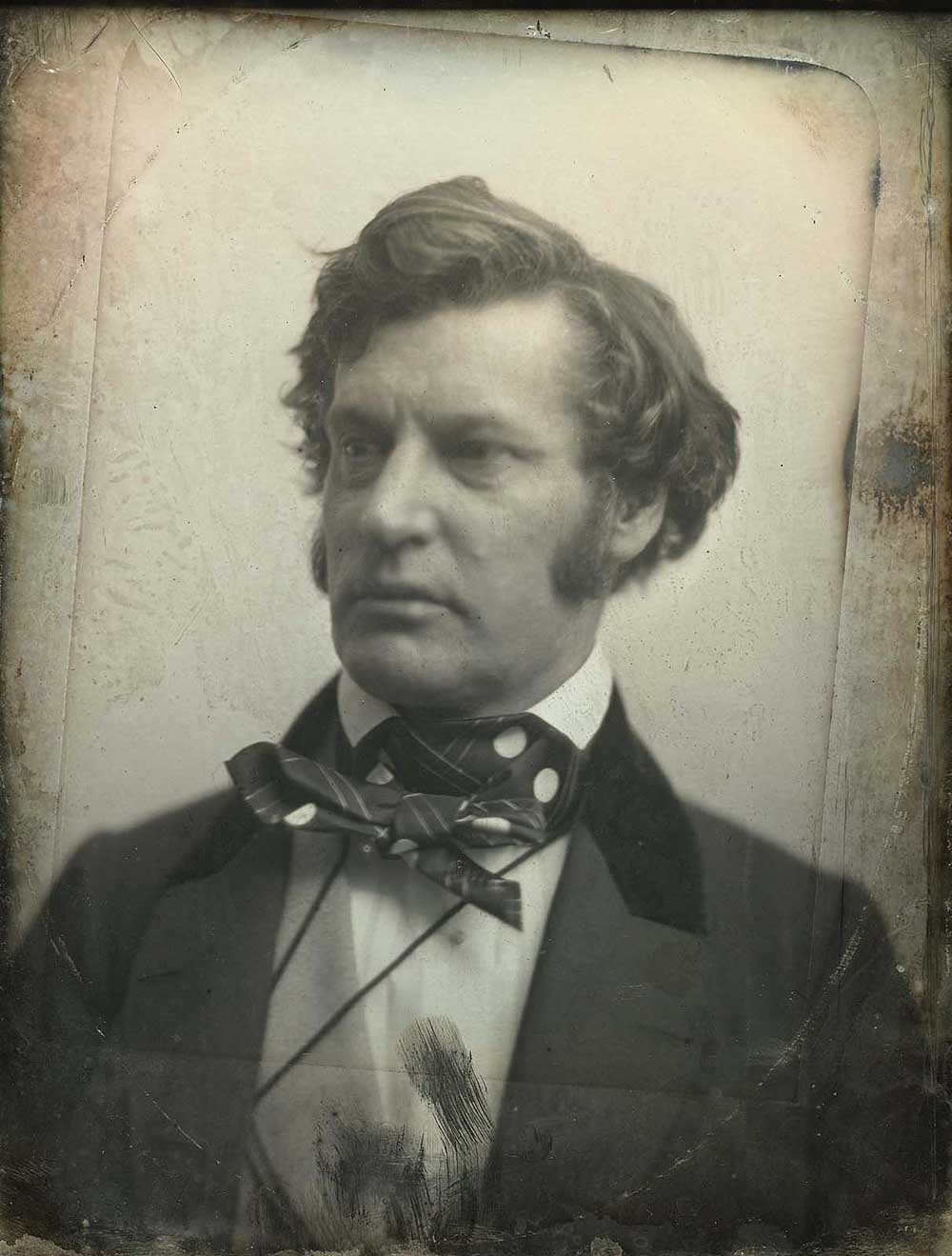

On December 2, 1872, the first day of the third session of the Forty-Second Congress, Massachusetts senator Charles Sumner introduced two bills on the floor of the U.S. Senate that were among his last. He expected the most important act he introduced that day to be the supplement to the Civil Rights Bill, which he had advocated since 1865. Although he expected little notice for the other bill he introduced that day, it caused a firestorm. Sumner sought to obliterate an aspect of the military memory of the U.S. Civil War.

Sumner’s proposed legislation sought to influence the memory of the U.S. Civil War by regulating the Army Register, the official record of conflicts and casualties, and the regimental flags of the United States. The very brief bill read, in full:

Whereas the national unity and good will among fellow-citizens can be assured only through oblivion of past differences, and it is contrary to the usage of civilized nations to perpetuate the memory of civil war: Therefore Be it enacted, &c. That the names of battles with fellow-citizens shall not be continued in the Army Register or placed on the regimental colors of the United States.

On its face, Sumner’s bill seemed concerned with national unity and recognized that Civil War memory—or the suppression thereof—would play an important role in the future “civilization” of the United States alongside the politics of African American equality that his Civil Rights Bill would seek to ensure. Sumner’s move against military memory, however, turned out to be one of the worst political blunders of his entire career, one that threatened his own legacy. He was censured by the Massachusetts legislature, while old friends and supporters turned on him.

Sumner underestimated the importance of the military conflict itself as the center of Reconstruction-era memory, favoring a political rather than military vision of the nation that he did not view as at odds with retaining an emphasis on emancipation and Black freedom. Sumner underestimated the allure of Civil War memory. Even though during the war he had twice proposed similar restrictions on regimental flags, his 1872 bill was considered a disavowal of Union heroism. A bitter enemy of President Ulysses S. Grant, Sumner had been effectively ejected from the Senate Republican caucus following his support of the Liberal Republican Horace Greeley in the 1872 presidential election just a month earlier. Sumner claimed that he had never abandoned the fight for African American freedom when he opposed Grant and supported the Liberal Republicans, but the Republican break and the Liberal Republican “new departure” further opened him to charges of disloyalty, especially when other Republicans might question his commitment to honor military accomplishments.

For Sumner, Grant was always too associated with warfare and therefore prevented sectional healing. Sumner’s biographer David Herbert Donald explains the flag bill as part of Sumner’s anti-Grant maneuvering, pointing out that he had told a campaign-season crowd in Massachusetts that the president could never “promote true reconciliation” because Grant himself was “a regimental color with the forbidden inscription” that would “flaunt in the face of the vanquished” their defeat in the war. Sumner’s 1872 flag bill made little progress in Congress; it was defeated by a joint resolution introduced in the House, which argued that “the national unity cannot fail to be strengthened by the remembrance of the services of those who fought the battles of Union in the late war of the rebellion.”

Even before Sumner’s bill died in Congress, however, he faced stiff opposition back in his native state because his resolution violated the politics of strong Union memory. Massachusetts chapters of the Grand Army of the Republic (GAR), many of which had strong Radical Republican commitments, had for years pursued political action based on the belief that “we cannot forget the past with its privations and sacrifices, nor forgive the treason which caused them.” The Massachusetts GAR was gaining strength after opposing the Liberal Republican ticket, and therefore breaking with the senator, in the 1872 election.

In condemning the flag resolution, Sumner’s Republican opponents in the Massachusetts House hoped to gain traction in the upcoming senatorial elections and felt that they could mobilize support from outraged veterans. On December 18 they introduced a resolution of censure against Sumner, calling his bill “an insult to the loyal soldier of the nation.” The Massachusetts legislature, which happened to be meeting in special session, passed the resolution quickly in one day after a series of parliamentary maneuvers gave Sumner’s supporters little chance to object. It took a fourteen-month petition campaign and a series of heated hearings to get Massachusetts legislators to rescind the act against Sumner in February 1874, just one month before the senator’s death.

Charles Sumner worried that the memory of Civil War battles would continue sectional division and overshadow the efforts to win African American rights, so he wanted to forget one and remember the other. He thought that to guarantee the passage of the Civil Rights Bill and finally protect Blacks would require sectional reconciliation that sidestepped the memory of Southern military defeat, which could stir up bitter hatred. Sumner fretted that military memory would eclipse emancipation and correctly anticipated what, in fact, would happen over the next several decades, as dominant strains of Civil War military memory both inspired continued Southern hatred of the North (enshrined in the Lost Cause) and created an image of sectional reconciliation based on the shared sacrifices of white Union and Confederate soldiers in battle that frequently drowned out Black contributions and emancipation struggles. He argued for a different kind of sectional reconciliation, one that suppressed the war and was cemented by political power.

Sumner was wrong, however, to believe that legislation could suppress military memory, let alone to think that Congress would be willing to try. He was shocked at the public outcry against his bill and against him, writing to Willard P. Phillips, “I cannot comprehend this tempest.” The press excoriated him; one paper called his resolution “an insult to every soldier and patriot who fought to save this government.” Thomas Nast caricatured Sumner in the December 28, 1872, issue of Harper’s Weekly as haughtily ignoring an amputee veteran, a soldier’s widow, and a war orphan who beg for congressional relief. The cartoon portrayed Sumner as manipulating Civil War memory: a paper in front of him read, “The only record of the rebellion shall be Charles Sumner and his speeches,” even as plans for “monuments and burying grounds for Union dead” and “U.S. History” lie in the wastebasket at his feet. Ironically, Sumner’s own reputation was the main thing threatened by his move to forget the war.

Political will to enforce issues of African American rights and equality, the great causes of Sumner’s political career, was already waning as Reconstruction showed signs of expiring in 1873 and 1874. In fact, many felt that Sumner’s Civil Rights Bill, passed by the Senate less than a year after his death, passed mainly out of deference to the dead senator (still nationally respected by Republicans even as he caused some controversy). In the following years the House of Representatives gutted the legislation, which it had never fully supported, and the Supreme Court declared it unconstitutional in 1883. Some African American leaders worried that with Sumner’s death their last strong legislative advocate had expired.

By taking on the politics of Civil War memory and trying to obliterate military accomplishments Charles Sumner threatened his own legacy and actually hurt his prospects of being useful as an object of public memory after his death. Sumner was well accustomed to being cast as a political symbol, having been considered a martyr to the cause of liberty ever since his 1856 caning. When he passed away in 1874, a great outpouring of public mourning issued forth—stretching from congressional obsequies in Washington, DC, to his burial in Massachusetts. But the memorials for Sumner were imbued with some of the same controversy that the senator himself had sought to prevent, in particular concerning what Americans should remember about the great issues of the Civil War.

Charles Sumner died early in the morning on March 11, 1874. He had endured poor health since his 1856 beating on the U.S. Senate floor, and his death was preceded by severe bouts of chest pain. Congress, already preparing to adjourn because of the death a few days earlier of former president Millard Fillmore, took immediate notice of Sumner’s passing. As national newspapers filled with notices of the senator’s death, Congress planned a grand funeral in the nation’s capital. On March 13 Sumner’s remains were brought from his DC home to the U.S. Capitol in a procession led by prominent African American men, including Frederick Douglass and P.B.S. Pinchback, who had defended Sumner when other Republicans had excoriated him for opposing Grant in 1872. Sumner’s body lay in state in the Capitol rotunda, attended by thousands of mourners, and spectators packed the Senate chamber—draped in black crepe for the occasion—to witness his funeral there. Congressional representatives, the president and vice president, members of the diplomatic corps, and other government officials also attended the rites. After the ceremony, Congress adjourned; a Massachusetts committee accompanied Sumner’s remains on a special train to New York and then on to Boston. After the funeral train arrived on March 14, Sumner’s remains lay in state in the Doric Hall of the Massachusetts State House, where tens of thousands of disorderly and sometimes rowdy men and women paid their last respects.

Sumner’s service and burial on March 16 became one of the largest civic funerals in Boston’s history. Even in the midst of all the public mourning that celebrated Sumner’s long political career, the flag bill controversy and the Massachusetts censure occupied a prominent place in the public memory of the senator. The Democratic New York World cast doubt on the sincerity of many of the accolades, noting that Sumner had died with a shattered reputation: “The generous American instinct which forgets all political differences on the brink of the grave insures to Mr. Sumner the usual pomp of eulogy, but the encomiums which will come from the lips rather than the heart cannot disguise the fact that, like poor Mr. Greeley, he died a brokenhearted man.” Sumner’s battles on behalf of African American rights and his caning by Preston Brooks occupied important space in his obituaries, but his more recent break with the Republican Party and the controversy over war memory clouded an unalloyed heroic picture of him in both Republican and Democratic papers. The World raged that public eulogies of Sumner were an “empty mockery” because he “was isolated and estranged from the party which owed him a great debt of gratitude.” The editors sought to use Sumner’s partial disgrace to score points against the Republican Party, even though party leaders denounced him for the flag bill, on the basis that “a party which thus casts aside its honored leaders has outlived its original principles.” Even as senators honored his dying words—“You must take care of the Civil Rights Bill…don’t let it fail!”—Sumner himself seemed to symbolize something of the disarray and partisanship of Reconstruction.

The timing of the censure’s removal gave Americans ample opportunity to be reminded of the flag resolution and to ponder and debate anew what Sumner’s attitude toward the Civil War’s legacy had really been. Newspaper reports of Sumner’s death were not able to heap praise on him without also refreshing the public memory of his censure. The day before his death, while on the U.S. Senate floor, Sumner had received the news from Massachusetts that the censure had been lifted. The Chicago Daily Tribune reported, “It is a rather singular fact that, on this last day in the Senate, and the last day that he was alive on earth and in the discharge of his duties, the resolution expunging the censure voted by the Massachusetts Legislature on account of his battle-flag resolutions were presented by his colleague Mr. Boutwell and read in his presence.”

Sumner’s political missteps in 1872 allowed him to be used as a symbol for a form of reconciliation that he did not actually support. Democrats and Southerners exaggerated Sumner’s political transformation by the end of his life; he opposed Grant, but he was still a strong advocate of Black rights and wished to be affiliated with the Republican Party. But his flag resolution had created a rhetorical opening to paint him as an advocate of total Southern forgiveness: it was framed as similar to Horace Greeley’s 1872 campaign plea that the North and South should “clasp hands across the bloody chasm”—an expression of unconditional absolution. Sumner wanted to continue using state power to enforce racial equality and Reconstruction policies, but most other Liberal Republicans wanted to end Reconstruction and supported Greeley’s notion that forgetting the war was the best path to reconciliation. By supporting the Liberal Republicans in 1872 and then proposing the flag bill, Sumner endorsed a form of forgetting the past that could be used to argue for the end of Reconstruction—even though he himself never went that far.

Some newspapers used Sumner as a symbol of a remarkably new national reconciliation. One Connecticut obituary exaggerated Sumner’s emphasis on Southern forgiveness, noting his achievements as a legislator and abolitionist and concluding, “Among his later efforts may be mentioned…his proposition to remove from public buildings the war flags captured from the confederate states during the rebellion.” The New Orleans Picayune pleaded, “Let the grave cover all that was inimical to Southern ideas and sentiments in the deceased senator, and let us only remember that he would have put away from the federal archives all show and sign of the triumph of countrymen over countrymen.” The Louisville Courier Journal editorialized, “Fifteen years ago the news that Charles Sumner was dead would have been received with something like rejoicing by the people of the South. Today they will read it regretfully, and their comment will be: ‘He was a great man. He was an honest man. As he has forgiven us, so have we long ago forgiven him.’ ”

From Spectacle of Grief: Public Funerals and Memory in the Civil War Era by Sarah J. Purcell. Copyright © 2022 by Sarah J Purcell. Published by the University of North Carolina Press.