By the age of twenty, Alice Liddell had perfected the art of becoming a photograph. In 1872 she patiently posed for Julia Margaret Cameron, enacting roles from mythology and literature as Alethea, Ceres, John Keats’ Saint Agnes, and Alfred Lord Tennyson’s Enid. The most compelling of these thirteen images is one of Alice staged as Pomona, the Roman goddess of fruitfulness. Alice appears half-length against a garden wall, framed by foliage and punctuated by Cameron’s hazy technique, one hand on hip, the other cupped in a gesture of offering.

There is a striking similarity between Cameron’s photograph of Alice as Pomona and one taken of her in 1858, when she was six years old. In Alice Liddell as “The Beggar Maid,” she poses as the title character from an 1842 Tennyson poem, set against a garden wall, foliage at her feet, right hand cupped while the left rests on her hip. In both, Alice’s blunt bangs frame her blankly direct address to the camera. The same pose and setting represent Alice as a child and adult, though she wears a new costume for her latest role.

By the time she stood in front of Cameron’s camera, Alice had years of practice transforming herself into a photograph, enacting fictions for the camera since she was only four years old. That’s when Alice met Charles Dodgson, then a stuttering, twenty-four-year-old math lecturer at Christ Church, Oxford, where her father, Henry Liddell, was dean. The meeting was life-changing for him, his niece later observed; one of “four notable things that happened to him” in 1856.

The same year Dodgson met Alice and the Liddells, he also “went to the theater for the first time, took up photography, and began to write.” It’s hardly a coincidence that Dodgson’s relationship with Alice was interwoven with a number of fictional narratives: the book, the stage, and the photograph. He would emerge from that year with a pen name far more recognizable than Dodgson: Lewis Carroll (an alias he eschewed in real life). Alice, too, would be transformed by the relationship, subsumed into Carroll’s many fictional creations of her, first into photographs. The literary Alice is undoubtedly the most famous of the many fictional Alices he conjured. In both Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland (1865) and Through the Looking Glass (1871), Alice’s identity is always in flux, always unstable. The shifts are so constant that when a denizen of Wonderland demands to know what she is, Alice can hardly answer:

“But I’m not a serpent, I tell you!” said Alice. “I’m a—I’m a…”

“Well! What are you?” said the Pigeon. “I can see you’re trying to invent something!”

“I—I’m a little girl,” said Alice, rather doubtfully, as she remembered the number of changes she had gone through that day.

“A likely story indeed!” said the Pigeon.

There is a confluence between the literary Alice and the Alice who stood before Carroll’s camera. The photographic Alice is also a production of imagination. In the enduring wonderland of Carroll’s photographs—where fiction abounds and the natural is made surreal—Alice is changed into an image. And like her literary counterpart, the photographic Alice raises a series of questions about identity, not only how it’s constructed, but also how one’s identity is understood by others. What kind of knowledge does photography provide about a person, if any at all? The most poignant question is perhaps the hardest to answer: What does it mean to become a photograph?

Those questions, central to photography itself, were especially pressing in the nineteenth century, as the medium’s practitioners explored the contours of what it was and what it could be, including its intrinsic potential as both a commodity and a tool of commodification. In Carroll’s images of Alice, produced a few decades after fellow Englishman William Henry Fox Talbot introduced reproducible photography, one senses a projective play in which Carroll is the sole author of the girls he photographed. The real Alice is the original, but as a fiction created and captured by Carroll, she is endlessly reproducible, his still pictures forever punctuated by her frozen look.

Although Carroll’s photography is often considered the lesser of his creative output, he was an avid photographer, producing around three thousand images during the two and a half decades he practiced. (Only roughly forty percent of his photographs survive.) He was likely introduced to photography by his comically named maternal uncle, Skeffington Lutwidge, who bought Carroll his first camera. Carroll had written to his uncle the previous year, imploring him to “get me some photographic apparatus, as I want some occupation here other than mere reading and writing.” In his catalogue, Dreaming in Pictures: The Photography of Lewis Carroll, Douglas Nickel suggests Carroll used photography as a distraction from the demands of Oxford life as well as a “passport” into the homes and social circles of Victorian tastemakers. And, indeed, outside of the Christ Church set, Carroll would photograph a number of contemporary luminaries, including the painter John Everett Millais and Tennyson.

Whether or not that was the case with the Liddell family is unclear, since Carroll’s personal journals from this period were largely destroyed after his death. (The period from April 1858 to May 1862 is missing, and other journals written during his relationship with the Liddells are missing pages or heavily edited.) Regardless of Carroll’s intentions, the surviving photographs of Alice and her sisters reveal an entirely modern sense of what photography does to a person, rendering them as a fictional object even while asserting meaningful knowledge about the sitter.

The earliest photographs of Alice, taken when she was four or five years old, do not pretend to sort through photography’s contradictions. Carroll’s first depiction of her from 1857 is an astonishingly plain image. She slouches in a chair, hands clasped in front of her, looking impatient before the camera. The photograph oscillates between light and dark, out-of-focus to sharp focus; the clarity of her hands contrasts with her round facial features, simultaneously both blurred and distinct. This particular Alice would be cropped and cut up into squares or ovals and pasted in many of the photo albums that Carroll created as gifts.

The early portrait shows Alice and Carroll’s parallel education in its infancy. He is learning to take a photograph—to render a clear image from wet collodion. Alice is learning that absolute stillness and total submission to the camera’s lens is pivotal to becoming a photograph. In the later pictures, their respective mastery of making and transforming into an image is clear.

Approximately fourteen of Carroll’s photographs of Alice survive. In some, she is captured in her daily costume while others captured her in states of undress or donning theatrical costumes. But whether wearing her own or other people’s clothes, in all the later photographs Alice was in masquerade—turned into photographic fiction. She plays a prescribed role, adopting poses from poetry and literature, and from the history of art. Instead of preserving Alice’s appearance, the camera fragments and refracts her, transforming her over and over, suggesting that photographic identity is infinitely variable.

In 1858 Carroll took three pictures of Alice, then six years old. The first of these, Alice Liddell in Profile, demonstrates not only Carroll’s increasing mastery of the medium but also his heightened awareness of photography’s potential as fine art. Moreover, it shows Alice’s increasing knowledge of how to become a photographic object. Her profile and the spatial effects, which throw her into relief, suggest the intaglio of a cameo or the inversion of her silhouette; this is the beginning of the slippage between the real Alice and her photographic counterpart.

Nowhere is this unstable identity more evident than in Carroll’s next two photographs of Alice—both full-length portraits that are visually linked. In the first of these, Alice Liddell Dressed in Her Best Outfit, Alice appears in clothes that belong to her, a costume appropriate to the creative class of which she was part. Alice is recognizable as Alice. And yet those characteristics that render her more herself are made uncanny by Carroll’s photographic scrutiny.

If Alice Liddell in Profile emphasized the play between fabric and camera, then Alice Liddell Dressed in Her Best Outfit introduces a greater mixture by opting for a full-length image and suggesting something of a context. Now, the texture extending from Alice’s dress interacts with the stone wall behind her and the vines creeping up that wall, which intermingle with the folds of her dress. The reflective surface of her patent leather shoes interacts with her lacy socks and with the garden plants upon which she stands. The technology of photography makes thoroughly ambiguous the difference between natural and artificial. Pushed into the photograph’s compositional corner, Alice is geometrically hemmed in by the photographic space given to her. In her book, The Politics of Focus: Women, Children, and Nineteenth-Century Photography, Lindsay Smith suggests Carroll’s propensity to place his child-subjects into these awkward spaces signifies his “geometric mastery” of space and “the encroachment of the point of view, of the photographer’s vantage-point.” In his photographs of Alice, one senses less a resistance to Carroll’s direction and rather a total capitulation to his terms. He is making Alice while also making her into a photograph.

The other full-length photograph from 1858, Alice Liddell as “The Beggar Maid,” offers a continuation on the themes of Alice Liddell Dressed in Her Best Outfit. She stands in the same location, once again framed by foliage and pinned into the corner of its walls. In both, there is almost a literal blurring between Alice’s body and the organic world, as if it were a natural act to stand perfectly still before Carroll’s camera. The provocative play between the natural and artificial resonates throughout each photograph. Add to that the likelihood that they were taken the same day. As a pair, the photographs speak to the mutability of Alice’s identity—her selfhood is, as in Wonderland, a mutable fiction.

Tennyson’s poem depicts an unnamed maid coming before the king and his court, all of whom admire her appearance through conventional praises of feminine beauty. The narrative is static and contemplative; it is a poem of description rather than of action, leading to resolution in the final two lines.

Her arms across her breast she laid;

She was more fair than words can say:

Bare-footed came the beggar maid

Before the king Cophetua.

In robe and crown the king stept down,

To meet and greet her on her way;

“It is no wonder,” said the lords,

“She is more beautiful than day.”

As shines the moon in clouded skies,

She in her poor attire was seen:

One praised her ancles, one her eyes,

One her dark hair and lovesome mien.

So sweet a face, such angel grace,

In all that land had never been:

Cophetua sware a royal oath:

“This beggar maid shall be my queen!”

Not surprisingly, the artists who had previously treated the subject matter chose to depict the crowning of the anonymous beggar maid. Carroll’s “The Beggar Maid” dissects the narrative, rupturing it photographically. He has removed any reference to Tennyson’s arc, relaying instead just the descriptive aspects of the poem: bare feet, ragged clothes, and the praised ankles. Alice as “The Beggar Maid” references only the role she plays and not a scene unfolding—Carroll’s photograph denies the mobility of the body. Alice is necessarily inert; the camera is lively. The clothes are a reminder that this is a wealthy girl playing at poverty.

In this respect, “The Beggar Maid” is not unlike a carte-de-visite of an actress posed in her signature role, photographs that married photography with the enduring fiction of celebrity. Isa Bowman, the actress who originated the role of Alice in the stage adaption of Alice in Wonderland, included in her 1899 biography of Carroll an account by one of the writer’s later models, Beatrice Hatch, of his costume closet: “He kept various costumes and ‘properties’ with which to dress us up, and, of course, that added to the fun. What child would not thoroughly enjoy personating a Japanese or a beggar child, or a gipsy or an Indian?” Though Hatch’s description suggests that other girls might have posed for Carroll as beggar children—a common subject for Victorian artists—only Alice’s theatrics have survived.

As early as 1860 Carroll began photographing Alice with her two sisters, Lorina and Edith. The photographs of Alice with her sisters open where “The Beggar Maid” concluded: meditating on what it means to be turned into a photograph and how it allows Alice to assume an array of different characters. In the first of these photographs, Lorina and Alice Liddell in Chinese Dress, the eldest Liddell sister, Lorina (known as Ina), and Alice wear similar costumes that Carroll maintained himself. Ina’s tentative stance is determined by the unfamiliar shoes on her feet; the propping-up of her left foot suggests an awkward balancing act. Once again Alice is dressed in clothing clearly not her own, but now she shares the transformation with her sister. Hatch was struck by the elaborate process of being dressed by Carroll, recalling the “rather awe-inspiring ceremony of being posed, with fastidious care.”

If the photographs of Alice by herself suggest a continual fragmenting and refraction by the camera’s glass, then the presence of her sister literalizes the allegory. By partnering Alice and Ina, Carroll proposes a doubling of photographic identity. The counterpart of the sisters’ appearances, their shared costumes and identical hairstyles, conflate one with the other, such that Alice’s identity is now intimately, if not incestuously, shared by Ina. The Chinese characters on the lower frame of the photograph are supposedly the girls’ names—Carroll has so thoroughly created their identities that the girls themselves are illegible to the people to which they refer.

In Carroll’s photographic fictions, identity was fungible—it could be shared between sisters or any of the girls who followed Alice, adopting her stillness and deadpan stare. In 1873, Carroll used her Chinese costume again, posing Xie Kitchin as both a Tea Merchant on Duty and a Tea Merchant Off Duty. Like Alice, Kitchin was the daughter of one of Carroll’s Christ Church colleagues; she appeared regularly in his photographs throughout the 1870s. Though Carroll had acquired more props and moved the setting inside, traces of the photographic Alice linger: her “Chinese” costume hat reappears in the images of Kitchin, and Alice’s vacant stare—no doubt learned to accommodate the long exposure time—also remains. (Notably, Carroll continued to use the wet collodion process in the 1870s, long after most photographers began using the dry-plate process, which had a significantly shorter exposure time.)

The pretend play-acting of Lorina and Alice Liddell in Chinese Dress found its counterpart in deceptively natural images of the sisters. Alice and Lorina Liddell in “See-Saw” (1860), likely inspired by Margaret Gatty’s 1855 story of the same name, depicts Alice on a seesaw while Lorina looks on. The youngest of the Liddell sisters, Edith, has been cropped out of the photograph but ostensibly is the weight that allows Alice to be suspended in the air. The picture shares peculiar similarities to Carroll’s posing of the sisters in Lorina and Alice Liddell in Chinese Dress. In this photograph, as in the other, Alice makes eye contact with the camera while Lorina, standing next to her, gazes outside the photograph’s visual field. The sisters’ matching hats, the similarity of their costuming, and Lorina’s stance (her right foot resting on the base of the seesaw) work together to create photographic fiction. This is further compounded by Alice’s position on the seesaw as she sits too close to the center of the object to allow for movement, a persistent reminder of the long exposure times demanded by wet collodion. (Plus, as Roland Barthes argued, the photograph “cannot say what it lets us see.”)

The second of Carroll’s staged constructions, Edith, Lorina, and Alice Liddell in “Open Your Mouth and Shut Your Eyes” (1860), presents all three Liddell sisters. Edith sits demurely on a table holding a plate of cherries as Lorina tempts Alice with fruit that she dangles above her upturned mouth. Based on the children’s nursery rhyme, “Open your mouth, shut your eyes, and see what Providence will send you,” this type of subject matter was popular among British visual artists in the mid-nineteenth century. It is a deceitfully skillful composition, as Alice’s hand braces against Lorina’s to hold the girls’ bodies absolutely motionless. But yet again one is confronted with numerous details that disrupt the photograph’s cohesion. Namely, the noticeable posedness of the sisters; especially that of Alice. Visible beneath Alice’s hemline and again at her waist is a headrest—a support commonly used to keep subjects from moving. The constructed stillness of the photograph rests on this artificial device that renders Alice motionless.

In Camera Lucida, Roland Barthes argues that the headrest is the “corset” itself: part of the clothing a sitter dons in order to be “transformed…into object.” The headrest is a “surgical prosthesis invisible to the lens, which supported and maintained the body in its passage to immobility.” The visibility of the headrest transforms it into a vital part of the scene, surgically attaches it, and conflates it with Alice herself. The headrest, like Alice’s costume and bodily fragmentation, is what constitutes her role in this photograph. It is a blatant acknowledgment of the act of being transformed into a photographic object, of becoming a photograph (in this case, both the photograph and its structure).

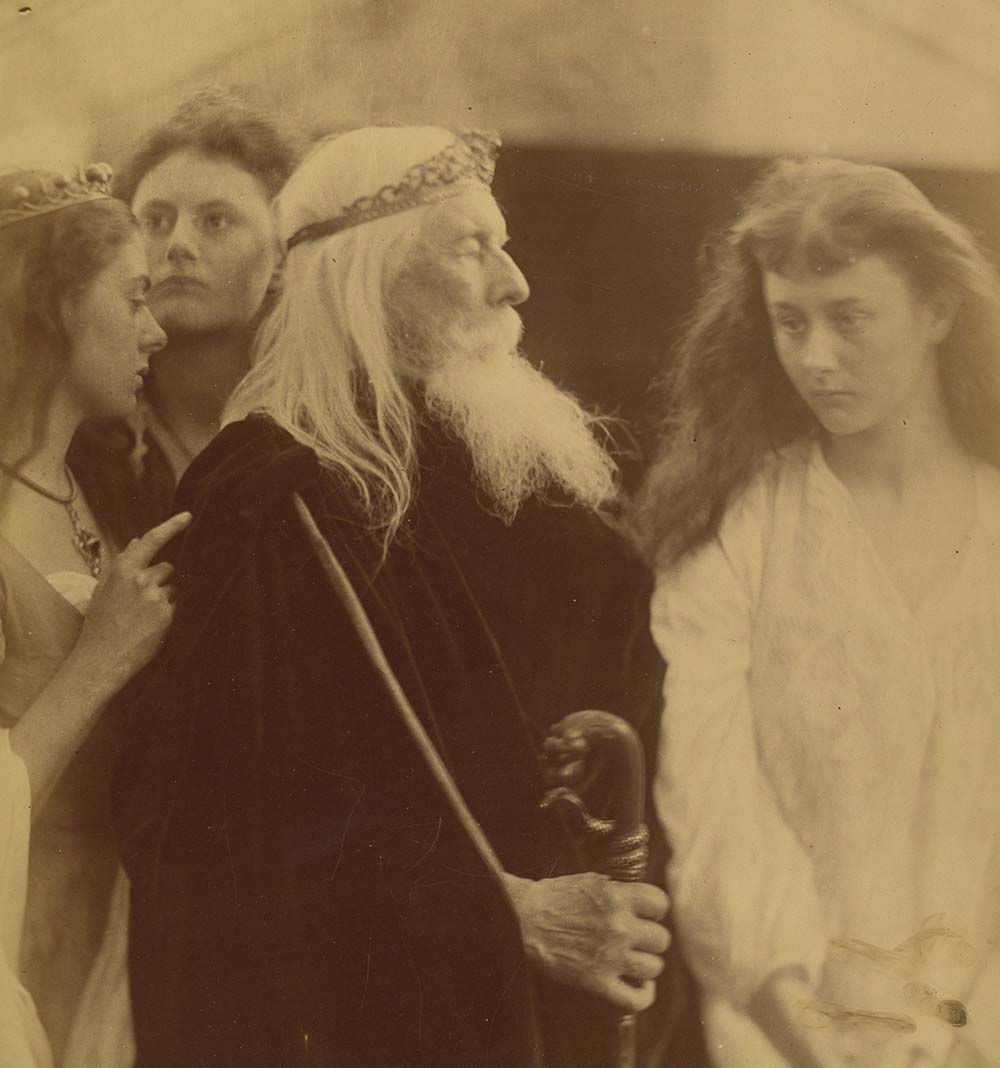

Carroll’s relationship with the Liddells abruptly ended in the summer of 1863. The reason is unclear—though it has been much speculated on. The diary pages covering this period were destroyed, leaving only a sentence fragment in which Carroll noted that he wrote to Alice’s mother, “urging her either to send the children to be photographed.” (The purpose “either” serves in the sentence remains ambiguous because the next page was removed. It also appears that someone attempted to erase the word “either,” since it’s been crossed out with different ink.) The Liddells never returned to be photographed by Carroll, but the sisters reappeared a decade later before Julia Cameron’s camera. Alice, Ina, and Edith posed for Cameron’s complicated tableaux vivants as Roman goddesses, literary heroines, and Shakespearean stories. In one photograph that typifies Cameron’s work, Alice and her sisters pose with her husband, Charles Hay Cameron, enacting a scene from King Lear. Charles plays the role of King Lear while the Liddells pose as his three ill-fated daughters, Ina’s index finger poignantly laid on his shoulder while Alice, hair down, fixes her gaze outside of the photograph’s frame, a look echoed by her younger sister Edith.

Alice seems to have faded from Victorian photographer’s lens, at least as a model. There are extant photographs of her practicing another role, Mrs. Reginald Hargreaves, becoming, as expected, an upper-class wife and mother. She would forever occupy an outsized place in Carroll’s imagination. In 1885, Carroll wrote to Alice:

My mental picture is as vivid as ever of one who was, through so many years, my ideal child-friend. I have had scores of child friends since your time, but they have been quite a different thing.

Alice proved to be the model for Carroll’s photographic direction; the original for countless reproductions of an enduring fantasy. Girls costumed in Alice’s guises, dressed as beggars and in Chinese costume, abound throughout the rest of his work. Like Alice, they have all been serially transformed into a photograph—an object that awaits a narrative to speak for it. In his photographs, she is little more than a “likely story indeed.”