When Paddington Bear set out for London in 1958, equipped with only a small brown suitcase and a tag around his neck imploring strangers to “Please look after this bear,” he claimed his homeland as “darkest Africa.” Of course, Africa is filled with all sorts of magnificent beasts, but bears, unfortunately, are not one of them.

Michael Bond, the creator of Paddington, was blithely unaware of this fact when he sent his manuscript to literary agent Harvey Unna, who swiftly responded enthusiastically, but with an important correction:

I have now read your novel, A Bear Called Paddington, and I think it’s quite a publishable tale and I like it well. My spies tell me, however, that you have slipped up in that there are no bears in Africa, darkest or otherwise…Children either know this or should know this and I suggest you make suitable amends for which purpose I am returning herewith the script. There are plenty of bears in Asia, Europe, and America, and quite a few on the Stock Exchange.

Unna was right. Africa is decidedly bear-free, though this wasn’t always the case. The Atlas bear (Ursus arctos crowtheri), a subspecies of brown bear, could be found in North Africa’s Atlas Mountains until around the seventeenth century, when hunting—likely following centuries of capture and trade for Rome’s arena games—pushed them to extinction in the wild. One source alleges that the king of Morocco still had an Atlas bear living in captivity as late as 1830 and even supplied another bear to the Zoological Garden of Marseille that same year, but those claims have never been substantiated. Certainly, by the time Paddington arrived at the railway station in the twentieth century, the African bear was a beast lost to time.

It was an embarrassing gaffe. To correct it, Bond set out for the Westminster Public Library to investigate other ursine candidates for the starring role in his story. A visit to the London Zoo in Regent’s Park followed. He passed through the park’s gilded iron gates and wandered down the paved path that took him past the penguin pool with its concrete waddle-ways and the zoo’s most famous resident, Guy, the western lowland gorilla. He saw fat grizzlies and Brumas the polar bear, but decided they would not do. They lacked the intrigue and exoticism he sought. After much deliberation, Bond settled on an enigmatic bear he had encountered in the library’s zoology collection: the spectacled bear (Tremarctos ornatus). Its small population in the jungles of South America seemed just right, and, though it was the only bear species found on the continent, not much was known about the animal. This would lend an air of mystery to his fictional stowaway, Bond thought, and so he returned home where he put pen to paper once more.

“You’re a very small bear,” said Mrs Brown. “Where are you from?” The bear looked around carefully before replying.

“Darkest Peru.”

There is an old temple at Chavín de Huántar. The archaeological site lies halfway between Peru’s tropical lowlands and the coast, near the confluence of the Mosna and Huanchesca Rivers, tucked between jagged mountain cordilleras. Inside the temple, a U-shaped flat-topped pyramid, intricate carvings of animals exotic to the highlands cover the stone passageways that form a labyrinth between chambers. Jaguars. Harpy eagles. Caimans. Anacondas. Devotees once came here to consult oracles and perform bloodletting rituals. In the middle of the central cruciform room, illuminated by a beam of sunlight, stands a fifteen-foot-tall, triangular granite monolith that connects the floor to the ceiling. A figure has been etched into the rock. Googly eyes sit above a broad snout with round nostrils. Curly hair ending in snake heads, like Medusa, frames a snarling face. One hand is raised in the air, palm forward, as if permitting passage to another world. The other lays down at its side. Five curving claws protrude from its feet, where worshippers once laid lavish gifts of food and ceramics. This is El Lanzón.

El Lanzón is the supreme deity of the ancient Chavín civilization, which flourished in this part of Peru between 900 bc and 200 bc. Scholars consider Chavín to be not only the mother culture of the Andes, but one of six pristine civilizations in world history deemed to be unique and not derivative of civilizations that came before. El Lanzón, its central figure, is purported to represent a key motif within Chavín art: the jaguar. Some anthropologists believe that the Chavín were even the founders of a jaguar cult and that those who visited the temple revered the ferocious characteristics of the big cat. But when conservation biologist Susanna Paisley looks at El Lanzón, she doesn’t see a jaguar. She sees a bear.

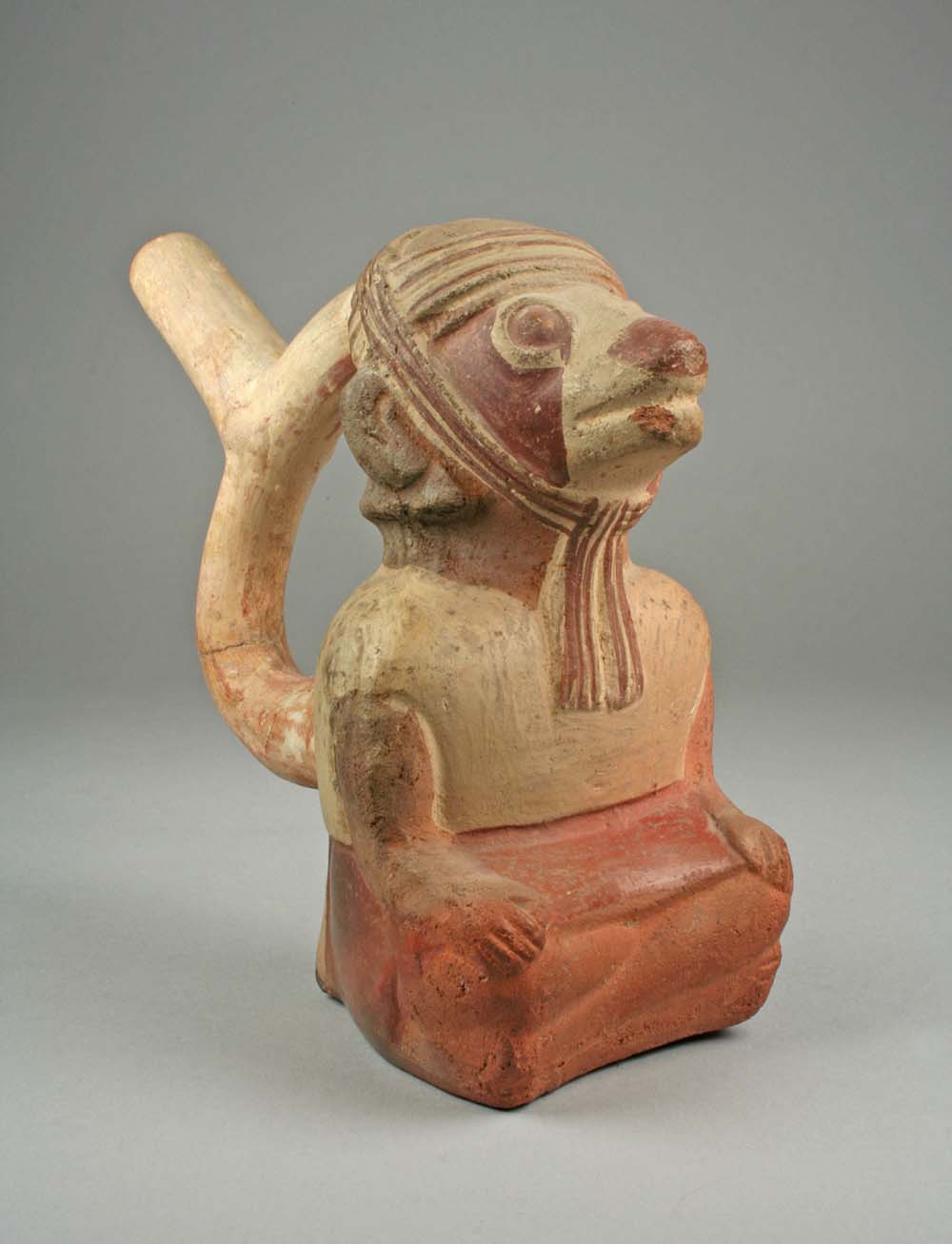

Despite England’s affinity for the marmalade-spattered Paddington, there’s a surprising dearth of spectacled bears in the ancient iconography of South America. The bear is noticeably absent in material artifacts from Incan and Amazonian cultures; there are no carvings, no pottery shards, no basket weavings created in the bear’s likeness. It was an absence that frustrated me as I strolled through the halls of the Pre-Columbian Art Museum in Quito—their animal exhibit had just opened—the Museum of Aboriginal Cultures in Cuenca, and the Museum of Pre-Columbian Art in Cusco. There were golden serpents and jaguar pipes and clay jugs shaped like fat monkeys, but not a single bear was to be found in the collections.

When I had bemoaned the bear’s absence to the biologist Russ Van Horn, he told me I should get in touch with Paisley, who had spent years in the forests of South America studying bears. She had since returned to the United Kingdom and was now creating stunning textiles drawn from a career spent in wild places. One pattern even featured the spectacled bear reclining in a tree whilst chewing on a bromeliad.

Paisley believes that the scarcity of South American bear iconography is no coincidence. Bears, much like jaguars, inhabited a large expanse of the vertical world in primitive times, she told me. Even now, spectacled bears are sometimes seen wandering among the ruins at Machu Picchu. The people of the Andes, she said, would undoubtedly have noticed the spectacled bear traversing the canopy or raiding their crops. She argues that bears aren’t lacking in representation because our ancestors deemed them irrelevant compared with big cats, but because they were so important to the early Chavín civilization that a taboo emerged around depicting bears in any tangible form that wasn’t El Lanzón.

Part of the blame for the bias toward the jaguar narrative, she thinks, lies with the circumpolar bear cult tradition, which holds that veneration of the boreal species of bears is a defining characteristic of cultures in the Northern Hemisphere, from the Sami in Scandinavia to the Inuit in Canada. As anthropologist Lydia T. Black put it, “Since Paleolithic times, most ursids have been a source of potent ritual symbols,” often offered as a sacrifice so that humans may communicate with the spirit world. Bears in the tropics, however, have been left wanting for attention. The attitude in South America, Paisley relayed, is along the lines of, “ ‘Bears are what the Gringos have. We have cats.’ ” She questioned whether this had led to a cultural blind spot. Were archaeologists failing to see the bears right in front of them?

While pondering the invisible bear, Paisley had a eureka moment: “All this time I’d been wondering if there were any early representations of bears, and then I looked down at the book I had on Indigenous South Americans. There was a picture of El Lanzón on the cover. I went ‘Holy shit! This is a bear.’ ” She wasn’t alone in such an interpretation. Van Horn had told me that nearly every other bear biologist who had seen a photo of the sculpture agreed with Paisley that it bore much closer resemblance to a bear than a jaguar. But the big-cat enthusiasts had already deemed the case closed.

Paisley eventually traveled to Chavín de Huántar to inspect the central deity. She took note of its erect posture—bears are fairly unique among the large mammals in being able to walk on their hind legs. Cats can only move through the forest on all fours, and most jaguar art reflects this quadrupedalism. Moreover, as Paisley observed, the monolith was reminiscent of the bear totems made by Indigenous tribes in the Northern Hemisphere. One paw up. One paw down. Archaeologists note that this position symbolizes a duality revered by ancient cultures—but it’s also oddly similar to the waving bear motif. And yes, the deity did have two protruding fangs that might indicate a jaguar. But plenty of circumpolar bear cult art pieces also depict bears with two gleaming canines. When I reviewed photos and drawings of the sculpture, I could see the bear’s likeness, too. The gravitas of such interpretation couldn’t be ignored. As Paisley wrote in the journal World Archaeology, “El Lanzón dwells at the center of the center” of Chavín culture. If her hypothesis is correct, the spectacled bear is not a forgotten beast of the tropical forest, but rather the singular most important animal in pre-Columbian Andean culture.

Russ Van Horn and I didn’t go to Chavín de Huántar. But we did stop in the small town of Paucartambo in the south of Peru on our way back from Wayqecha. The town, bisected by a rushing river draining the Andes’ melting glaciers, appeared unremarkable from the road. We crossed a worn cobblestone bridge to arrive in a plaza fringed by pale stucco buildings with cobalt-blue shutters and doors. In the center stood a large golden figure.

The statue’s face was covered in a ski mask. Its eye slits were pointed toward the heavens. Bent legs straddled a decorative pile of rocks and cacti. A shapeless, shaggy tunic cloaked its body. Muscular arms and a vascular neck protruded from the unseemly frock, clutching a smaller figure slung over its back: a young girl with sculpted curls. Her dress was hoisted up to midthigh and her sandaled feet flailed out behind her. Her fist was raised high in the air, as if about to beat down on her emotionless captor: the Ukuku.

The Ukuku is a mythical creature said to be half man, half spectacled bear that falls outside of whatever taboo exists around physical ursine artifacts in South America. These bear-men travel the Andean highlands in Bolivia and Peru as mediators of social life. They link highland with lowland, human with animal, sickness with health, and order with chaos. That’s the benign definition, anyway. The Ukuku—the Indigenous Quechua word for bear—is best known for another defining trait: stealing and raping women. In Incan mythology, the bear is “strongly associated with human fertility and sexuality, notoriously running off with shepherd girls,” Paisley wrote in World Archaeology. Many highland sagas tell of the arrival of a bear-man, or bear disguised as a man, who kidnaps young women and hauls them off to a cave where he rapes them. Other versions feature wanton women offering up their virginity to the bear-man, believing him to be God incarnate. Sometimes this unnatural coupling yields a hybrid offspring of immeasurable strength.

I learned that many young women in the Andes fear the real spectacled bear, conflating the animal with the Ukuku. In childhood, parents tell their daughters terrifying tales of bear abductions and sexual assault. Karina Vargas, a machete-wielding biologist I encountered in Peru, often worked in Indigenous Q’ero communities in the highlands around Paucartambo, and she told me that some women refused to go into the forest alone because of the legend of the bear. I suspected the creepy sculpture in Paucartambo’s plaza probably didn’t help matters.

“Yeah…it is a rather troubling statue,” Van Horn acknowledged as we appraised the Ukuku in all its lecherous glory. Rain pounded down.

“Mhm.” I nodded. “It looks like a serial killer.”

The Ukuku, despite its proclivity for sexual assault, isn’t considered all bad. Every June during Qoyllur Rit’i, the largest native pilgrimage in the Peruvian Andes, tens of thousands of revelers travel to Sinakara Valley, about 30 miles southeast of the Wayqecha field station in the high mountains. Here they celebrate the Snow Star Festival, a colorful mishmash of Catholic, Incan, and Indigenous beliefs, honoring not only the return of the Pleiades star cluster at the start of the harvest, but also Jesus Christ and the apus, mountain gods.

At the festival’s riotous base camp, a special group of men don tubular fringed robes and pull knitted masks over their faces to become Ukukus. (Previous incarnations saw them drape spectacled bear pelts across their shoulders.) The Ukukus then hike 5 miles up the valley—more than sixteen thousand feet above sea level—with the other pilgrims to the Qullqip’unqu glacier. At the edge of the ice, only the potent bear-men are allowed to continue on the path, traversing the perilous glacier to hold an all-night vigil where they pray to gods and fight condemned souls. When dawn breaks, the Ukukus chip blocks out of the ice and race down the mountain with the frozen cargo strapped to their backs. Waiting pilgrims greet the ice with untempered joy. They mix it into healing elixirs and pay homage to the ice to ensure a good harvest.

Yet even the mythical bear-man cannot escape the ravages of climate change. Peru’s glaciers shrank by nearly a third in the last two decades, forcing the Ukukus to hike much farther to reach the retreating Qullqip’unqu terminus. And where once each Ukuku carried his own block of ice down from the mountain, the government began curtailing the collection in 2000 by permitting only a few of the Ukukus to set foot on the glacier. A few years later, the Ukukus announced they would no longer carry ice down from the glacier, expressing concern about the future of the fragile landscape and wishing to play no part in its demise. After all, they were destined to protect the mountain gods; if the glaciers were ailing, removing ice would only hurt the deities. Now the Ukukus return empty-handed.

I pictured Paddington standing in his neat blue duffle coat and floppy red hat on the railway platform. Before his death in 2017, Michael Bond told the Guardian that he was inspired to create the bear after seeing evacuated children trudging through Reading Station during World War II as bombs battered Europe. Each carried only a small suitcase of their most treasured possessions. The children had permanently left behind one world and would soon enter another. “I do think that there’s no sadder sight than refugees,” Bond had said. I thought of the spectacled bear resting on an untidy shelf of sticks up in the cloud forest canopy. I thought of the vanishing clouds. I thought of the mining explosions ricocheting through the bear’s home. In Bond’s hands, the spectacled bear was a parable for the plight of thousands of human refugees and the cost of war. Now the animal was fulfilling Paddington’s fiction. If deforestation continues unabated, the spectacled bear, too, would become a refugee, pushed away from its homeland, never to return.

Excerpted from Eight Bears: Mythic Past and Imperiled Future by Gloria Dickie. Copyright © 2023 by Gloria Dickie. Used with permission of the publisher, W.W. Norton & Company, Inc. All rights reserved.