Napoleonic Wars operations in Holland surveyed from a captive balloon, by Jan Anthonie Langendyk, 1805. © The Trustees of the British Museum.

On a November evening in 1782, Joseph Montgolfier contemplated the print of Gibraltar hanging above his fireplace. The middle son of a family of prominent bourgeoisie papermakers in the otherwise unimportant northern French city of Annonay, Joseph was an unlikely daydreamer. The drab environs might have sent his mind wandering elsewhere for excitement and possibility, a trait that occasionally landed him in debtors’ prisons over ambitious if ill-planned business ventures, including a brief foray into dye making and a paper mill that died from inattention.

As the embers flickered and the night air cooled, Joseph considered the means by which France might seize this tiny island and thereby control its strait—through which the majority of Europe’s trade passed into Mediterranean. No other acquisition of that size could compare with Gibraltar’s importance as France looked to rebuild its empire. But how to wrest this natural and nearly impenetrable fortress from its current Spanish occupants without a prolonged military campaign?

But just then, according to Charles Coulston Gillispie, the biographer of Joseph and his brother Étienne, Joseph noticed the vectors of heat rising from the fire. It occurred to him the answer might be: by air.

He fashioned a hollow sphere from taffeta and wood, placing at its base a small basket into which he twisted paper ends that he lit with a match. The miniature hot air balloon rose to the rafters—and with it man’s ambition for militaristic control of the skies.

Recognizing the larger implications of his idea even in this fledgling form, Joseph dashed off a note to his brother. Étienne expertly ran the family’s paper business while deftly modernizing its production methods. The two were very much each other’s opposite and as such ideally suited to collaborate on this fantastical invention of precision engineering.

After experimenting with different shapes, sizes, and materials for just under a year, they were ready to launch their first full-size craft. It resembled a contemporary air balloon, though about a third of the size. A small crowd gathered in Annonay’s town square on a rainy June day to watch the launch of the first Montgolfière, as the brothers’ balloon would come to be known. To their astonishment, it began to inflate. It rose to an estimated three thousand feet and flew a mile and a half before landing in a vineyard, where the grape pickers may well have thought the moon had fallen from the sky. By the following summer, news of the brothers’ invention reached Versailles, and King Louis XVI and Marie Antoinette requested an exhibition. The Montgolfiers happily obliged.

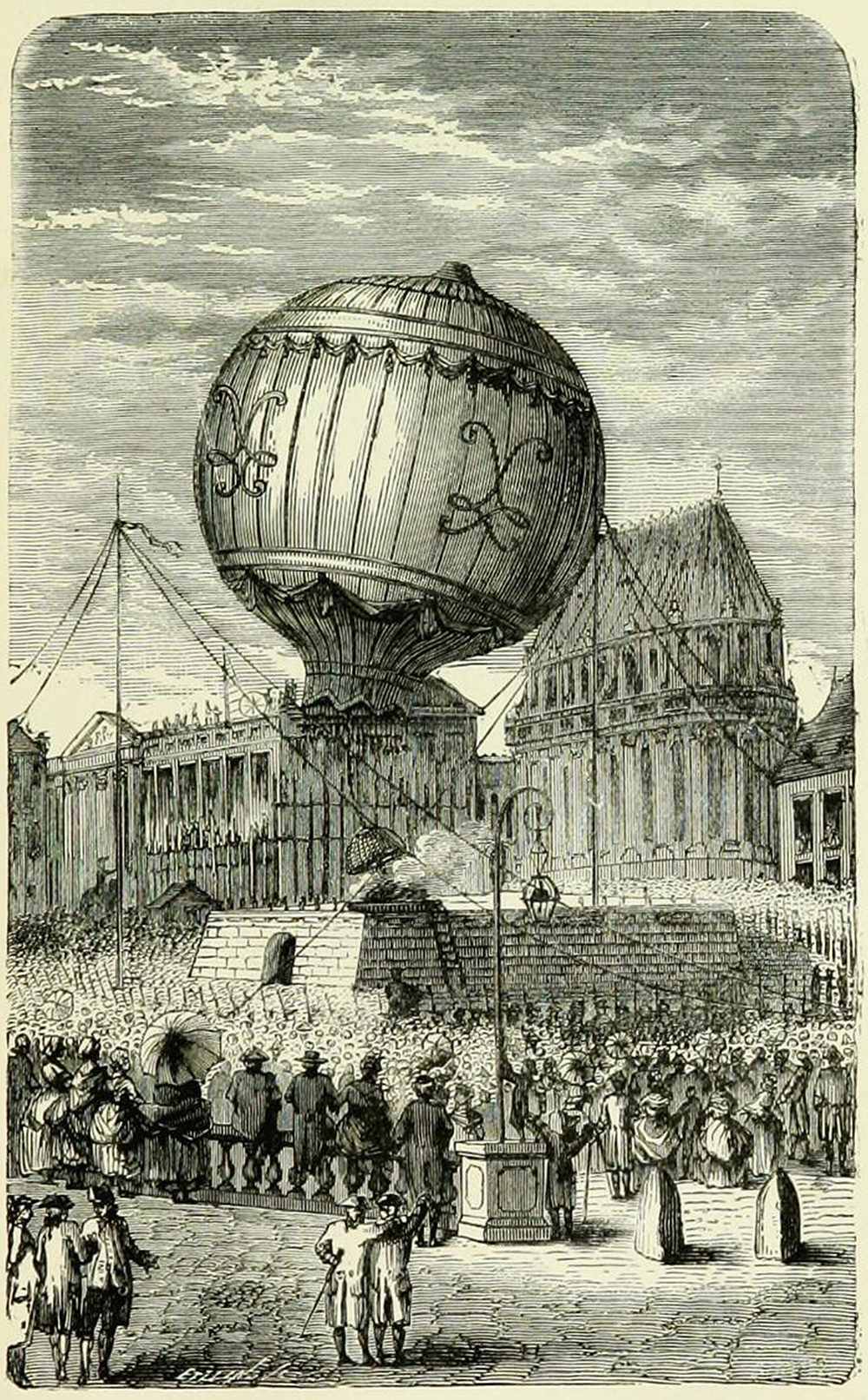

The royal reveal occurred on a sunny day in September 1783. The monarchs were perched in their box, looking down at the palace’s courtyard as an enormous expanse of cloth ornamented with zodiacal signs interspersed with flaming suns and gilded fleurs-de-lis seemed to stir and rise of its own accord. Meanwhile, the Montgolfiers furiously fed bale after bale of hay into the balloon’s furnace. The balloon soon took shape, then flight, gliding peacefully above Versailles’ opulent gardens. The crowd below was stunned, and more still stared agape at morning newspapers heralding the feat the next day. But some observers took a more sanguine stance toward this lighter-than-air orb, comprehending almost immediately its potential application in war.

Perhaps chief among them was Benjamin Franklin, who had been present at the royal launch. Not long after, he wrote a friend:

Five thousand balloons, capable of raising two men each, could not cost more than have ships of the line; and where is the prince who can afford so to cover his country with troops for its defense, as that ten thousand men descending from the clouds might not in many places do an infinite deal of mischief, before a force could be brought together to repel them?

He was not alone in fantasizing about airborne armadas. One English pamphlet published in 1783 argued hot-air balloon aeronauts could observe and report on enemy strength and positioning as well as monitor the movements of one’s own troops. Another the following year proposed “the construction of a grand naval balloon.”

France was not to be outdone by these lofty visions of aerial assaults. Just over one year after this Versailles display, the mathematician and engineer Jean-Baptiste Meusnier de la Place presented the French Academy of Sciences with schematics for a new kind of flying machine driven by an engine and steered by a propeller. In other words, he introduced the world to the idea of a dirigible.

Despite the fervor for militarized airpower, hot-air ballooning in the service of war wouldn’t progress beyond theory for the next ten years. Then the French Revolution changed that.

By 1793 the newly minted French Republic faced the First Coalition, an international alliance composed of Great Britain, Austria, Prussia, Russia, and a number of smaller monarchies that didn’t like the idea of a heretical republic. At home, France’s de facto governing body, the Committee of Public Safety, had been co-opted by Maximilien Robespierre, who was busy hoisting his egalitarian machine of death above the heads of some 16,600 supposed political opponents. Turmoil churned within the civilian population. Desertions in the military spiked. If the Republic was going to prevail, it needed a secret weapon. The revolution’s political leaders in Paris hoped the hot-air balloon would fit the bill.

Numerous aspects of the Montgolfiers’ balloon made it unsuitable for battle. It would be difficult to transport the hundreds of pounds of fuel required to fill the balloons and keep them afloat. The inflation process could take hours—longer still if it rained. If this invention was to have any practical application in war, the revolutionary forces needed a way to produce the fuel on site and inflate balloons beforehand.

The solution, improbable as it might seem given that the calendar had not yet turned to the eighteenth century, was hydrogen.

While hydrogen balloons known as aerostats had been flown before, the contemporary methods of producing the lighter-than-air gas made them unfeasible for the purposes of war. The first scientists to experiment with such balloons manufactured the hydrogen by combining sulfuric acid with iron filings in a corked wine barrel. The reacting contents slowly escaped the barrel through a glass tube that transported the gas into a balloon. This method was obviously dangerous and could literally blow up in an experimenter’s face. The process was also slow and arduous and didn’t produce a tenth of the hydrogen the military would need. On top of that, sulfuric acid was a key component in manufacturing gunpowder, which was already in short supply thanks to France’s multifront war.

Luckily, another method of hydrogen extraction had been tried, though not entirely proven, by Antoine-Laurent Lavoisier. The French noblemen and chemist had discovered the fuel could be extracted by passing water over incandescent iron, which oxidized the iron and freed the hydrogen. (His experiments also happened to be the first to yield the composition of water.)

The Committee of Public Safety tasked Lavoisier and a team of fellow scientists to explore this potential avenue of hydrogen production. The researchers quickly showed promising results. Despite his contributions to the cause, Lavoisier was convicted of unrevolutionary activities and guillotined one month after his method proved suitable for the military’s needs.

In his place, Nicolas-Jacques Conté, a self-taught inventor, and Jean-Marie-Joseph Coutelle, a brilliant chemist, stepped in to solve the problem of how to scale production. In a matter of months the pair developed a furnace capable of filling an aerostat balloon at an unprecedented rate of forty-eight hours. These balloons could be inflated months before they were needed.

Demonstrating their achievement to the increasingly powerful Committee of Public Safety, Conté and Coutelle took its members up for rides in pairs. Upon returning to earth duly impressed, the politicians voted to establish compagnie d’aérostiers, or the Company of Aeronauts, the world’s first air force.

The timing was propitious. The war was not going well.

The Committee dispatched its newly formed company of aeronauts to join General Jean-Baptiste Jourdan in the Low Countries during the summer of 1794, hoping for a French comeback. Though one of the revolution’s most celebrated figures, Jourdan was coming off a string of minor defeats and had just been driven south by an inferior Austrian-Dutch army. When the aeronauts arrived, he was preparing to face Friedrich Josias, prince of Saxe-Coburg, for an engagement that would come to be called the Battle of Fleurus.

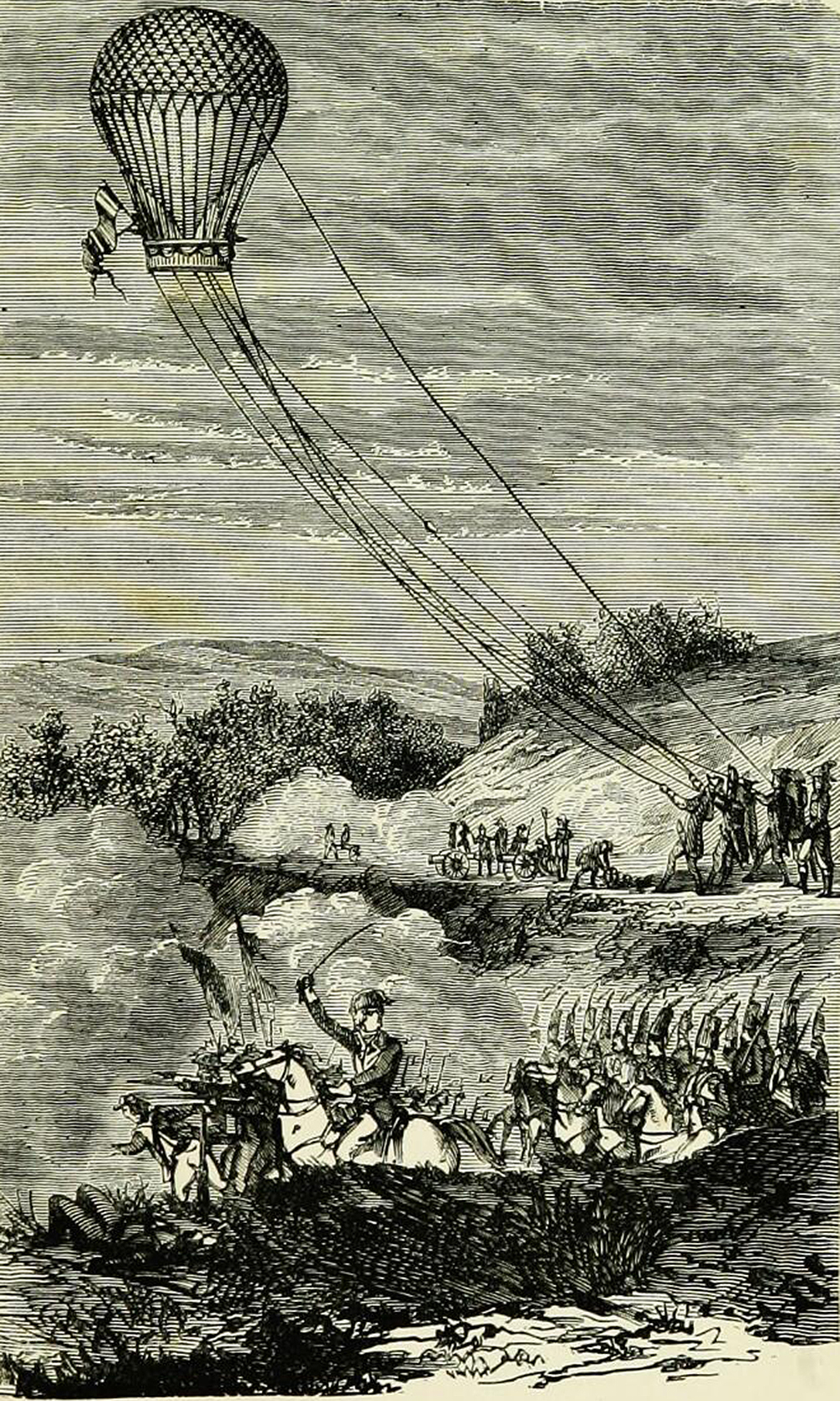

As the opposing forces gathered, the compagnie d’aérostiers constructed a mobile version of Conté and Coutelle’s furnace with cast-iron pipes measuring approximately eight feet in length. Once up and running, they began to inflate L’Entreprenant, a purpose-built spherical balloon with an enormous diameter of twenty-seven feet. While the armies marched toward each other on the morning of June 26, two aeronauts ascended in L’Entreprenant while sixteen soldiers held them fast in place, in effect forming a mobile watchtower.

From their elevated view, they watched Friedrich Josias split his battalions into five columns, a strategy that allowed each to react more quickly to the developing battle conditions. This preflight maneuver worked at first, and the Austrians broke through France’s left and right wing, concentrating their assault on the army’s center column.

Despite being fired on and almost shot down, the airmen of L’Entreprenant reported on the enemy’s movements through flag semaphore and written messages tossed to their compatriots below from ballast-filled bags attached to the balloon. As the battle raged for five, ten, and then fifteen hours, the aeronauts’ observations allowed commanders to adjust their tactics with an accuracy of information previously unknown on the battlefield. This new instrument of war reportedly terrified the Austrians, whose advantage slipped away. When the smoke cleared, the French proved to be the victors.

More than an isolated skirmish, the engagement was a crucial turning point in the war, and the world took note of the aerostat’s contribution. As one commentator in the British Register wrote of France’s employment of an aerostat in battle, “the assembled armies of her enemies have witnessed those advantages, and the gaining of the battle of Fleurus was the consequence.”

Soon after this crucial victory by the republican army the coalition of monarchies withdrew across the Rhine. The French pursued, floating their airborne watchtowers above the battles at Maubeuge, Charleroi, and Gosselins, as well as the 1795 campaign along the Rhine.

But the evolving realities of revolution soon interfered with the progress of state-controlled airpower.

Fueled by fear of international invasion, the Terror lost its raison d’être after the Ancien Régime’s coalition was driven back to whence they came. Robespierre lost his head, and the cooler ones that prevailed had little use for the revolution’s more radical aspects, including its thirst for experiments in military ballooning. By the time Napoleon was crowned first Emperor and France, for all intents and purposes, reverted to its prerevolutionary ways, the compagnie d’aérostiers had been disbanded and the exploits of L’Entreprenant relegated to the history books.

Yet the idea of an air force did not dissipate so easily. In 1803 John Money, one of England’s first aeronauts, urged the British Army to adopt balloons into their field operations. In his widely circulated pamphlet A Short Treatise on the Use of Balloons and Field Observators in Military Operations, he often rendered his arguments in verse.

Great use, he thought, there might be made

Of these machines in his own trade

Now o’er a fortress he might soar

And its condition thence explore;

Or when by mountains, woods, or bog

An enemy might lie incog

Our friend would o’er their station hover

Their strength, their route, and views discover

Five years later, on the other side of the channel, one of the original members of the compagnie d’aérostiers put a new twist on that age-old French fantasy of invading England by suggesting they do so aboard a fleet of a hundred balloons.

Hot-air balloons and aerostats did not disappear from battle entirely. In 1807 the Danes endeavored to break an English blockade by attempting to bomb their ships from hot-air balloons. In 1849 the Austrians attempted to lay siege to Venice by way of incendiary bombs strapped to hundreds of unmanned hot-air balloons.

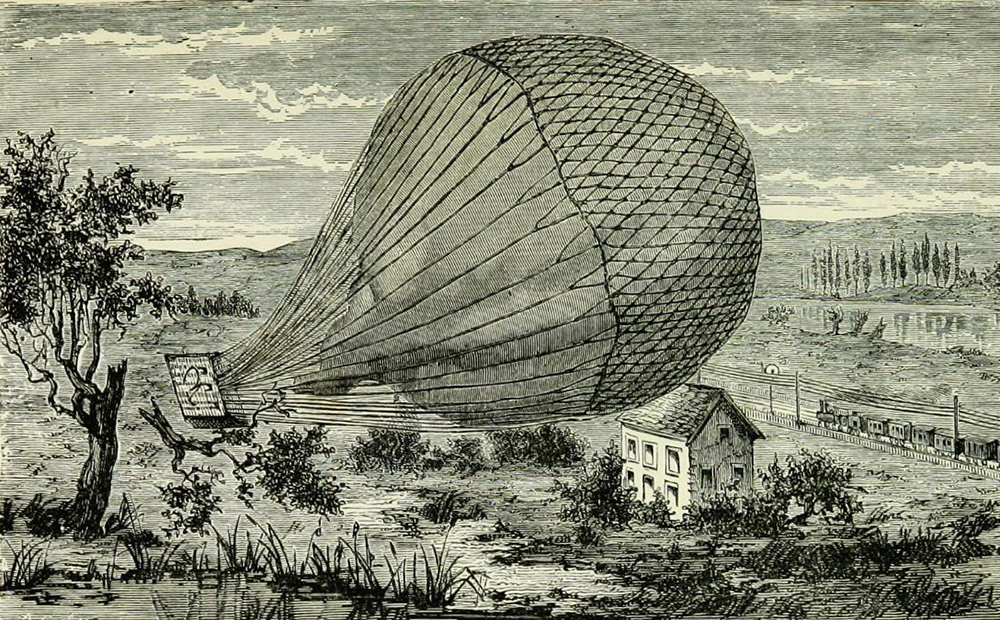

Besieged during the First Italian War of Independence in 1848–49, the defenders of Milan floated pamphlets, proclamations, and general propaganda to the surrounding areas in the baskets of miniature hot-air balloons. Balloons and aerostats were also used for reconnaissance during the American Civil War as well as the First Boer War, just to name two of many instances.

But even though the basic tenets of airpower—reconnaissance, communication, and combat—had been seeded during the French Revolution and established well before the calendar rolled over to a new century, few truly recognized just how significant those initial forays into airborne combat really were.

Not until Kaiser Wilhelm II’s zeppelin bombing raids of London did the world begin to recognize airpower as the future of warfare. Twenty-two years later the Luftwaffe, Royal Air Force, and the U.S. Air Force ended any debate that remained. With astounding rapidity British Spitfires, German Heinkels, and American Wildcats were followed by Sputnik, the Space Age, and the nearly nine thousand satellites that were subsequently launched—some for peaceful purposes, others to guide ICBMs to targets the size of single-car garages.

Below them, spy planes now proliferate in the upper levels of our stratosphere while ever more sophisticated fighter jets fly a thousand feet down. Closer still to the ground are remotely piloted combat drones armed with payloads of the world’s most advanced weaponry. Together these machines form concentric circles of war that we now take to be as intrinsic to Earth as rings are to Saturn.

Though man’s timeless infatuation with the gods of war may well have made the weaponization of the heavens inevitable, one wonders when and by what path were it not for these early instruments of flight. Arriving in the midst of a revolutionary age and right before history became modern, balloons seem to have silently ushered in a new age of global warfare without anyone really noticing that these rudderless aircraft had a definite direction after all.