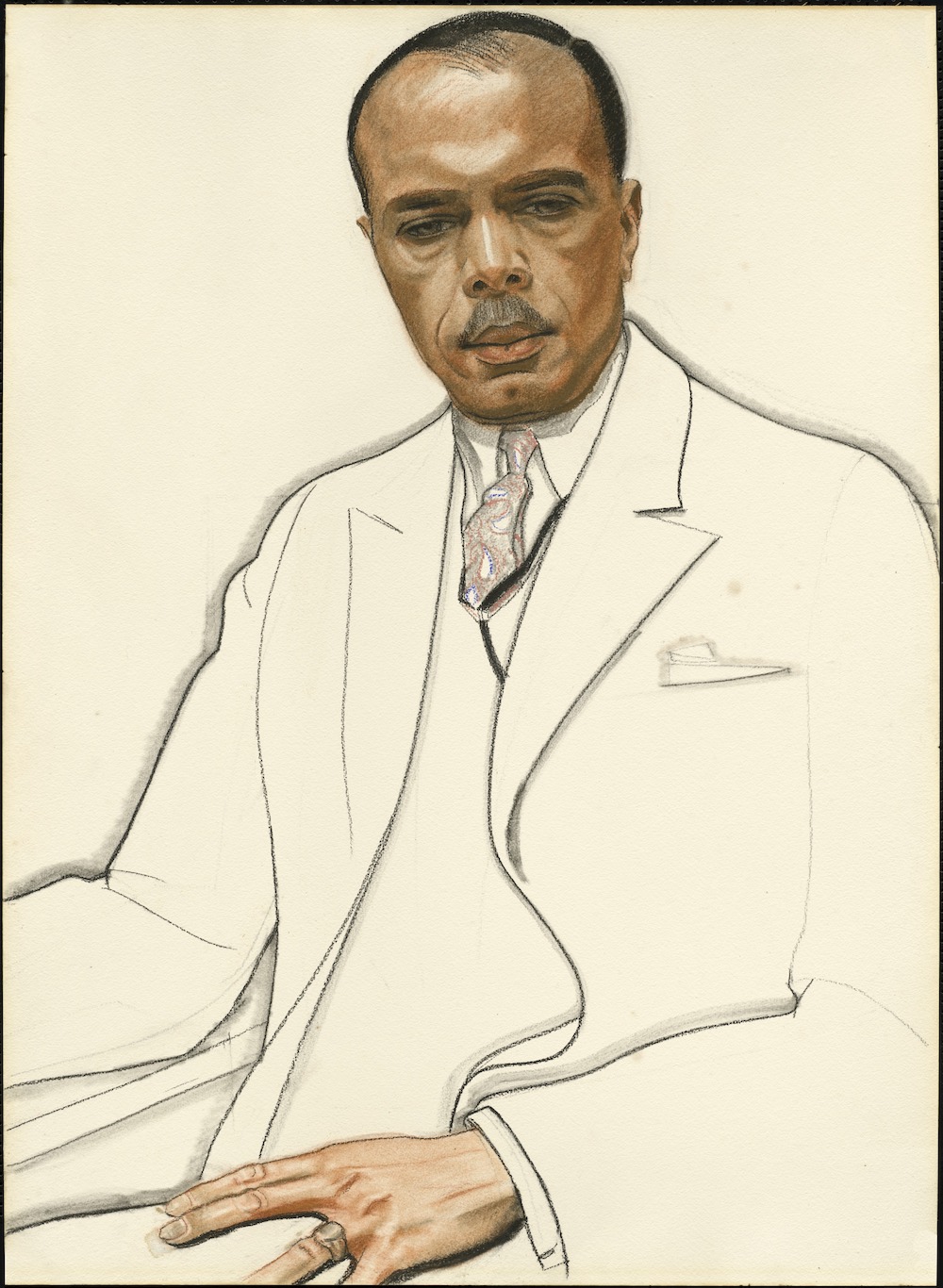

Silent Parade in New York City protesting the East St. Louis riots, 1917. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

As people continue to gather across the world to protest police brutality and anti-Black racism, Roundtable will feature voices from the past who rose up against injustice and told stories or witnessed moments that rhyme with the ones unfolding before us.

During and after Reconstruction the United States saw a series of riots where white mobs attacked, intimidated, and killed African Americans. Some of the earliest race riots took place in and around polling stations—attempts to prevent Black Americans from exercising their voting rights. Early twentieth-century race riots were more likely to result from white anger over Black wealth, and white mobs frequently engaged in the concerted destruction of Black-owned property. The East St. Louis riots, also called the East St. Louis massacres, were a series of labor- and race-related riots that took place in May and July 1917. White mobs marched through East St. Louis, attacking Black residents and burning their homes and businesses. Estimates suggest that rioters killed up to 250 African Americans and left thousands more homeless. In the aftermath, ten thousand Black Americans marched silently through New York City in a protest known as the Silent Parade.

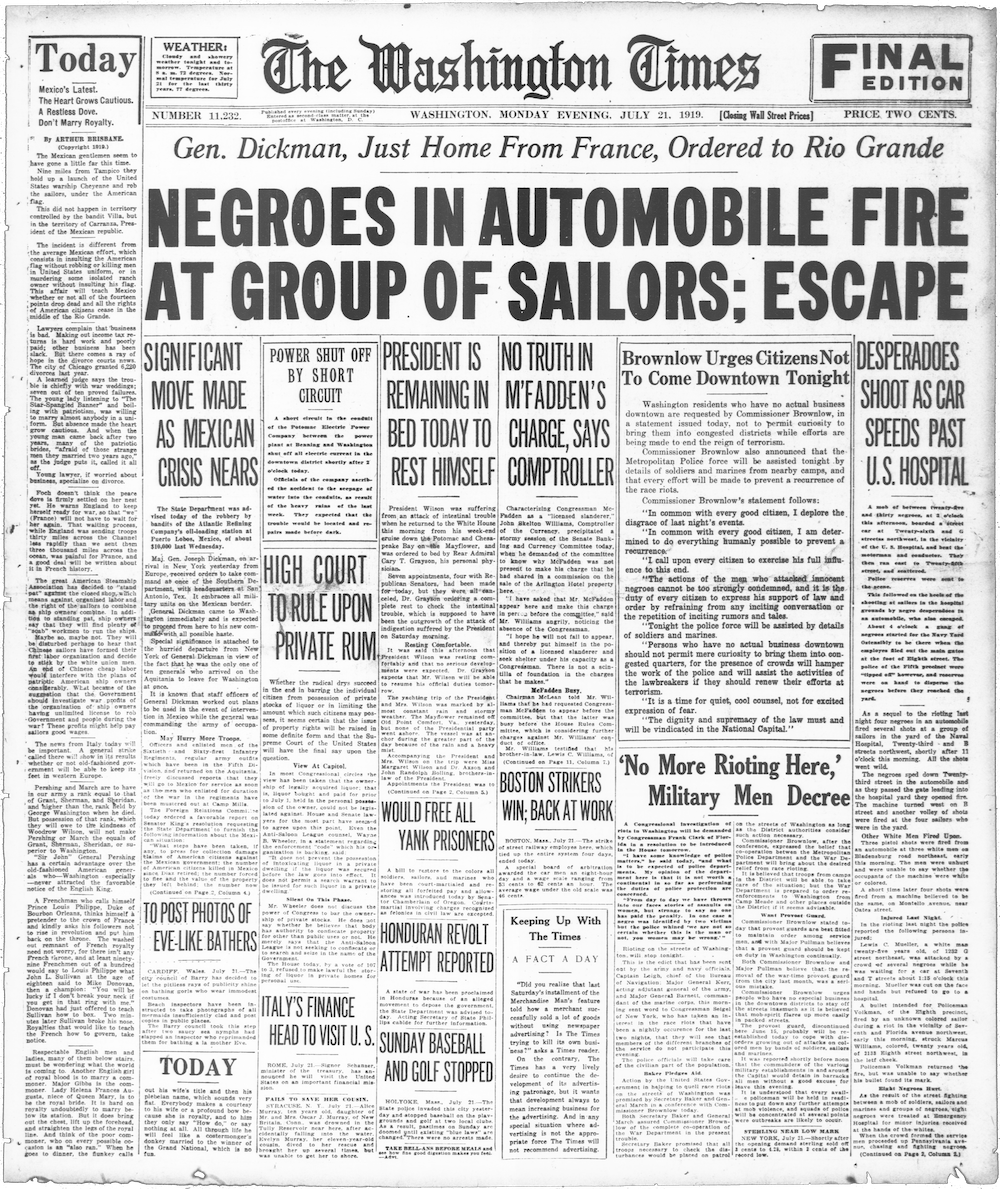

The spring and summer of 1919 saw so much racialized violence and civil unrest across the United States that it became known as the “Red Summer,” a term coined by the writer, civil rights activist, and NAACP leader James Weldon Johnson. Hundreds were killed and many more were injured in white supremacist attacks and race riots in dozens of locales across the country. The riots in Chicago and Washington, DC, stood out both for their high death tolls and because Black Americans rose up to fight back against the violence perpetrated against them. The DC riot, which began on July 19 and continued for five days, left fifteen people dead and over 150 wounded.

Johnson, who had served as U.S. consul to Nicaragua and Venezuela in the Roosevelt administration, traveled to the capital to talk with public officials and the media about how to solve the problems underpinning the violence. He wrote the following report on his trip for the September 1919 issue of The Crisis, the NAACP magazine.

I reached Washington early in the evening of July 22. As the train neared the capital I could feel the tenseness of the situation grow. It showed itself in the air of the passengers as they read the newspapers, with their glaring headlines telling of the awful night before and intimating that the worst was yet to come. As I passed through the cars on my way to the diner and back, men and women glanced up at me with what seemed to be a look of mild surprise; with a glance which seemed to say, “This man must indeed have very important business in Washington.”

The porters and waiters plainly showed the strain under which they were doing their work—the strain of suppressed excitement with, perhaps, an added sense of dread of going into something, they knew not what. They moved about quietly, in fact, grimly and entirely without their customary good humor and gaiety. One of the porters who knew who I was questioned the wisdom of my going through with the trip. I may have felt that his question was not absolutely without reason, but I did not admit it. When I left the car he said to me, “Take good care of yourself.” I assured him that I would spare no effort to do so.

I had made many trips to Washington—some as a mere visitor, some as a member of the government’s Foreign Service, some for the purpose of placing for the NAACP matters affecting the race before men high in authority and position; and so I had experienced varied emotions on making the trip to the nation’s capital, but none like the emotions experienced on this trip. I knew it to be true, but it was almost an impossibility for me to realize as a truth that men and women of my race were being mobbed, chased, dragged from street cars, beaten, and killed within the shadow of the dome of the Capitol, at the very front door of the White House. It was almost an impossibility for me to realize that, perhaps, my own life would not be safe on the public streets.

When we reached the Northwest section of the city, I found the whole atmosphere entirely different. I had expected to find the colored people excited and, perhaps, panicky; I found them calm and determined, unterrified and unafraid. Although on the night before shots had blazed all through the night at the corners of Seventh and T Streets and Fourteenth and U, I could detect no signs of nervousness on the part of the colored people living in the section. They had reached the determination that they would defend and protect themselves and their homes at the cost of their lives, if necessary, and that determination rendered them calm.

Still, under the outward calm, there was a tautness that could be sensed. Wild rumors had been circulating all day foreboding terrible things; and these things, whatever they might be, the colored people had made up their minds to meet. But as darkness came on, the rain began to fall, and later it fell in torrents; so it may be that the rain had something to do with the things that did not happen.

That evening I met with a half dozen of the influential colored men of the city. We talked over what had happened and discussed the steps already taken by the authorities and by the colored citizens and such steps as we thought it well to take on the following day.

The next morning Herbert J. Seligmann1 and I had a conference with Major Raymond W. Pullman, chief of police, regarding the protection of colored citizens. At this interview Mr. Seligmann secured for the information of the national office and for purposes of publicity data regarding all the alleged cases of attacks on women which had been put forward as the cause of the riots. Our conference with Major Pullman lasted an hour; he expressed a desire to have us talk with Commissioner Louis Brownlow and made an appointment with him for us at two o’clock in the afternoon. Before we left Major Pullman’s office a committee consisting of Dr. Austin M. Curtis, young Dr. Arthur Curtis,2 and Emmett J. Scott,3 accompanied by Captain Doyle of the 8th Police Precinct, came to ask that the police department swear in a number of colored men as special officers to aid in preserving law and order. Mr. Seligmann and I remained and gave our support to the committee. However, it was plain that Major Pullman was not favorable to the plan. He suggested that the committee take the matter up with his superior, Commissioner Brownlow. Mr. Seligmann and I then informed the committee of our appointment with the commissioner at two o’clock, and invited them to go.

In the afternoon we had a long conference with Commissioner Brownlow. The whole situation was gone over, and the plan of commissioning colored men as special officers was brought up. The commissioner was stronger in his opposition than the chief of police.

In the evening I attended a meeting of the executive committee of the Washington branch of the NAACP to learn what the branch had done and was doing, and to offer such suggestions as I might. I found that the branch had been active as far back as July 9, when it sent a strong letter to all four of the Washington daily papers, calling their attention to the fact that they were sowing the seeds of a race riot by their inflammatory headlines and sensational news articles; after the outbreak of the riots a committee had been appointed that went before Commissioners Brownlow and Gardiner and before Major Pullman to urge that effective action be taken to prevent assaults upon defenseless colored people who were the victims of the attacks. Members of the legal committee had spent considerable time in court in connection with the trials of the men who had been arrested for carrying weapons for their protection. A committee was set at work obtaining affidavits from victims of the riot who had been wounded or injured. And at this meeting the legal committee was authorized to interview all colored persons charged with rioting and offer them legal assistance.

On the following morning I went to the Capitol and talked at length with three influential senators. I went over the whole situation, not only local but national, with these senators, and did my best to show them what I considered to be the principal causes of the trouble. I also spoke to each one of them regarding a congressional investigation of the whole question of mob violence. I was able to secure from one of these senators, who has been in Congress for twenty-five years and is a member with experience and prestige, and who is also a strong advocate of justice for the Negro, the promise that he would father a resolution calling for such an investigation and a printed report on the same.

In the afternoon I went to the office of the Washington Post and talked with the city editor. It was the Post that on Monday morning had published the “Mobilization for Tonight” call to the idle servicemen in Washington to meet near the Knights of Columbus hut, on Pennsylvania Avenue, and organize a “cleanup.” When I handed the city editor my card, he appeared glad to see me. He seemed to be under the impression that I had come down from New York for the express purpose of telling the colored people in Washington to be “good.” He called a reporter and asked me to tell him what the NAACP was doing and proposed to do in the matter.

I lost no time in telling him that the organization I represented stood for law and order, that all the fights it had made on behalf of the colored people had been made through and under the law, but that my reason for calling on him was not to discuss that phase of the situation. I then proceeded to tell him frankly and directly how responsible were the Washington Post and the other Washington dailies for what had taken place.

I talked with him for perhaps half an hour. During the whole time he stood as one struck dumb; at least he answered not a word. I realized that the man was scared through and through. He asked me before I left if I thought the riots were over. I told him I thought they were, unless the whites again took the aggressive. I was surprised to see the next morning that the Post published some of the things I had said.

The next day, accompanied by Mr. R.C. Bruce,4 I made similar visits to the offices of the Washington Times and the Washington Star. In the afternoon I talked again with one of my senators. At night I left for New York.

I returned disquieted but not depressed over the Washington riot; it might have been worse. It might have been a riot in which the Negroes, unprotected by the law, would not have had the spirit to protect themselves. The Negroes saved themselves and saved Washington by their determination not to run but to fight—fight in defense of their lives and their homes. If the white mob had gone on unchecked—and it was only the determined effort of Black men that checked it—Washington would have been another and worse East St. Louis.

As regrettable as are the Washington and the Chicago riots, I feel that they mark the turning point in the psychology of the whole nation regarding the Negro problem.

1 A writer and civil rights activist, Seligmann was the author of The Negro Faces America, Race Against Man, Alfred Stieglitz Talking, and other books. He served as publicity director for the NAACP from 1919 to 1932. ↩

2 Austin M. Curtis was a well-respected Black surgeon. His son Arthur, also a surgeon, had served in World War I. ↩

3 Scott served as special assistant for Negro affairs to the secretary of war and was the highest-ranking African American official in the Wilson administration. ↩

3 R.C. Bruce served as assistant superintendent of Black schools in Washington, DC. ↩

Read the other entries in this series: Anna Julia Cooper, Claude McKay, Walter F. White, and a Haitian hymn.