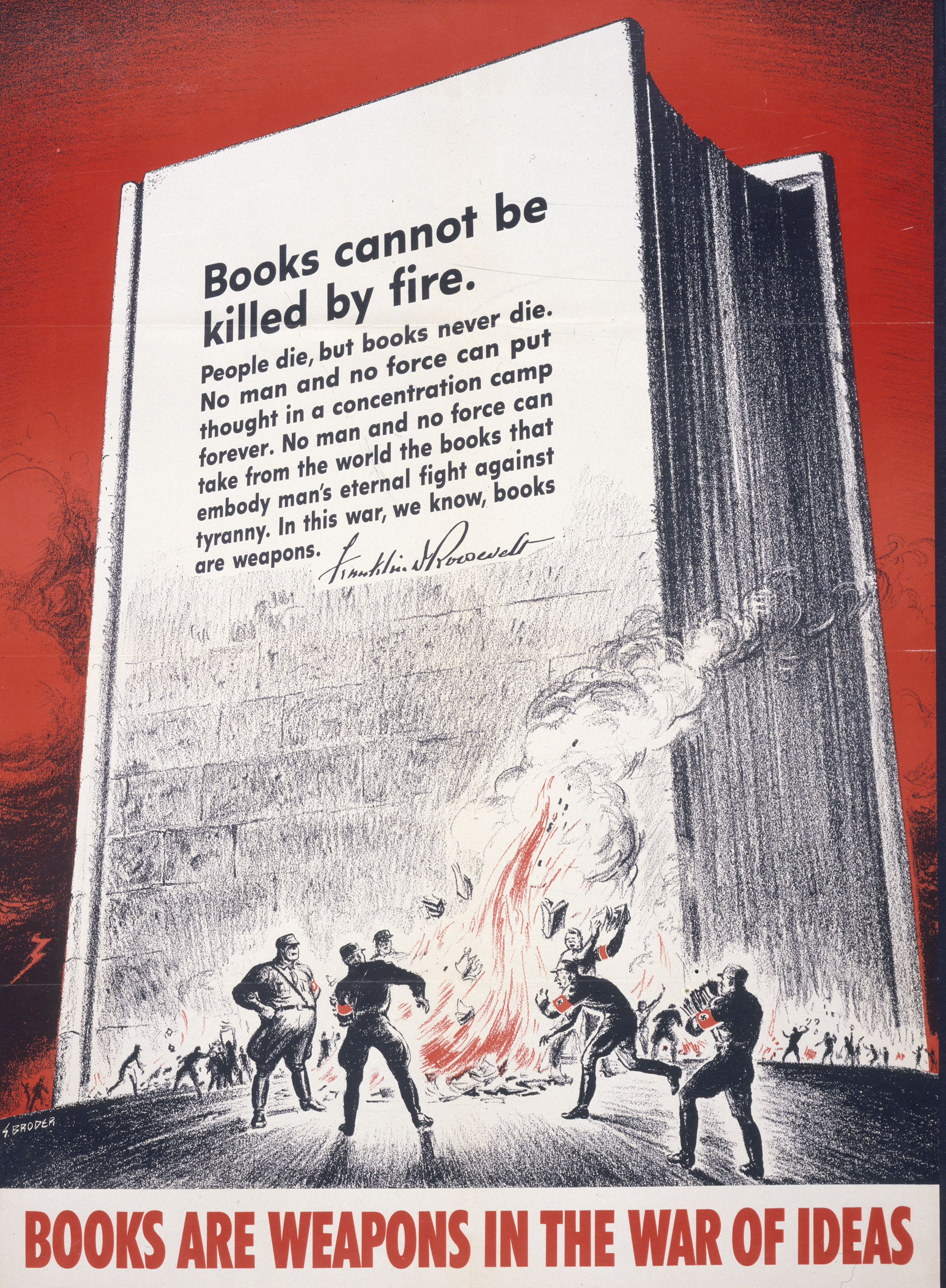

Poster showing Nazis burning books, by the Government Printing Office, 1942. Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division.

The Allies signed Order No. 4, on the “Confiscation of Literature and Material of a Nazi and Militarist Nature” on May 13, 1946. It prohibited works that promoted Nazism, fascism, militarism, racism, völkisch ideas, antidemocratic views, and civil disorder. It required schools, universities, and public libraries, as well as booksellers and publishers, to remove these works from their shelves and deliver them to Allied authorities; they would then be “placed at the disposal of the Military Zone commanders for destruction.” American officials must have assumed that Order No. 4, as an extension of earlier policies, would attract little notice when they announced it in Berlin that day. Instead, reporters clamored for explanation and demanded a second briefing. In a hastily organized press conference that night, Vivian Cox, an ex-WAC and a low-level assistant in the Armed Forces Division, was called in to address the skeptical crowd. She told them that a single passage could condemn a book and “billions” of volumes might be seized. “Was the order different in principle from Nazi book burnings?” they asked. “No, not in Miss Cox’s opinion,” reported Time. This was a front-page story: Americans were burning books.

There were numerous practical and philosophical challenges in executing the principles of occupation and reconstruction, manifested in the handling of Nazi and militaristic literature. What would it take to transform the defeated nation from tyranny to democracy? As Feliks Gross, a Polish émigré and sociologist involved in educational reconstruction, put it, “Under what conditions do the character and ideals of a nation change?” That question might have applied as well to the Americans: How would they navigate the contradictions of being a “democratic occupier,” using coercive and repressive means to achieve democratic ends? There were no easy answers where books were concerned.

American and British experts began to tackle the problem of how to deal with German publications as early as 1943. Books fell under the purview of different military and civilian governmental agencies that sometimes worked at cross-purposes. Educational materials were handled separately from publishing and the book trade, with libraries falling somewhat in both camps.

The policy toward German textbooks emerged in the collaboration of two groups in wartime London, the informal Working Party on German Re-Education, led by Oxford scholar E.R. Dodds, and the Education and Religious Affairs (ERA) section of the German Country Unit, which planned the military occupation. Seemingly unaware of the shifting political winds in Washington, the ERA imagined a reconstructed Germany that would be like the Weimar Republic. After their first handbook was criticized “for being too ‘soft’ in its policy toward the Germans,” they stiffened their approach to denazification.

The policy called for the elimination of all schoolbooks that had indoctrinated youths with the malign tenets of Nazism and militarism. Few changes had been made to textbooks in the early years of Hitler’s regime, except for the inclusion of new prefaces and introductions touting National Socialism, which could be excised or pasted over. By 1937, however, Nazi ideology permeated students’ daily lessons: physics books applied “scientific principles to war uses, biology and nursing texts had long chapters on racialist theories, while algebra texts were filled with examples and problems based upon the use of artillery, the throwing of hand grenades, the movement of military convoys, and so on,” the ERA reported. History and geography had been rewritten to highlight the losses caused by the Versailles Treaty; Latin readers glorified strong leaders and individual sacrifice to the state. Allied education planners wanted such textbooks impounded and replaced. They decided initially to reproduce Weimar-era texts as a stopgap measure and planned to publish new works authored by non-Nazi German educators.

On its face, the military government’s perspective was simple: Nazi books were akin to a virus or infestation that required quarantine and elimination. If this seemed self-evident to many, underlying this view was an array of social science research. To a remarkable degree, the American military developed its media policy by seeking the counsel of psychologists, public-opinion researchers, sociologists, and German émigré intellectuals. For decades, communications experts had warned of the power of media to influence a mass audience. Some had specifically investigated state control and media indoctrination in totalitarian countries, while others considered how Americans could fend off such influences and build morale through effective propaganda. Émigré social theorists, such as Franz Neumann and Herbert Marcuse, also shaped perceptions of Germans’ psychological state under Nazism and reinforced the need for thorough cultural change. The OSS even interviewed Thomas Mann and other prominent German writers, who thought that “Nazi education and literature must be stamped out,” yet “placed little confidence in teaching democracy from books.” Although contradictory, their suggestions leaned toward using the methods of totalitarian propaganda and indoctrination in the service of democratic values. “We had much advice from those who professed to know the so-called German mind,” commented General Lucius Clay sardonically. “If it did exist, we never found it.” Nevertheless, transforming the “Nazi mind,” as it was often called—and thus the German reader—became a problem of postwar reconstruction.

Not everyone agreed that banning books with Nazi or militaristic content was the solution, and they questioned the psychological and political impact of such a policy. An unnamed official argued that the experience of defeat had exposed Nazi propaganda for what it was. “To any but the impressionable juvenile mind, ‘objectionable’ literature in print has been largely if not wholly debunked by the catastrophe which the war has brought upon the German race,” he wrote. “From a psychological point of view,” he mused, “it might be a good thing to require every German adult to reread Mein Kampf and its derivative literature following our occupation!” Others recognized the attraction of the forbidden: Would Germans resurrect and reread works that otherwise would have gathered dust? They discussed previous instances of book prohibition, including efforts to restrict pornographic literature in England and the United States. Above all, they wanted to avoid accusations that the Allied policy was a “repetition in reverse” of Nazi practices of book burnings.

Public libraries and universities were initially seen in a different light. The Handbook for Military Government, issued in December 1944, had ruled that books in these libraries “not be removed, impounded, or destroyed.” Education and Religious Affairs in particular favored unrestricted access to any library material, drawing a distinction between adult reading and required school textbooks. Through the spring, however, the policy hardened. Local army commanders closed libraries and ordered librarians to halt the circulation of objectionable works, although this effort was haphazard. New guidelines hammered out in June made clear that public libraries were to be brought into line with publishers and booksellers. They required that all forbidden materials be removed from open shelves and placed in secure rooms, available only with the express permission of the military government. Staff members filled out Fragebogen, detailed questionnaires intended to reveal Nazi affiliation or beliefs. Library directors were required to sign a certificate stating, “I fully understand that it is my responsibility to see that the library is completely denazified.” Applications to reopen a library certified that “no ardent Nazi will be employed” and no literature circulated that supported Nazi doctrines, militarism, or discrimination on the basis of race, nationality, creed or political opinion. Once approved, military government officers had the authority to reopen noncommercial libraries. Similar rules applied to university libraries. Academic librarians segregated objectionable volumes in rooms that could be used only by authorized researchers. Into the fall of 1945, these materials were largely works by prominent Nazi authors or those with explicit militaristic ideology, such as Clausewitz’s On War or biographies of Bismarck.

Removing Nazi literature from German homes proved to be a red line. Although a committee drafted a directive to this effect, it aroused strong opposition in the U.S. Control Council. To accomplish this goal, one general objected, they would need not only a vast index expurgatorius of “tens of thousands of titles” but also armies of inspectors to search every home and bookshelf. “The ease with which printed matter can be concealed is obvious,” he said. Even more than these practical matters, however, the Control Council balked at an action reminiscent of Nazi book burning: American public opinion would be outraged, and Germans would perceive this as a hypocritical and punitive measure. Even the Nazis had not gone on house-to-house searches for banned books. A counterproposal recommended a publicity campaign to encourage Germans to voluntarily give up their Nazi books as “an act of personal cleansing or expiation” that would convert tainted works into paper pulp and new reading matter. This idea was repeatedly raised, especially by the British, as an alternative to coercive measures.

From Information Hunters: When Librarians, Soldiers, and Spies Banded Together in World War II Europe by Kathy Peiss. Copyright © 2020 by Kathy Peiss and published by Oxford University Press. All rights reserved.