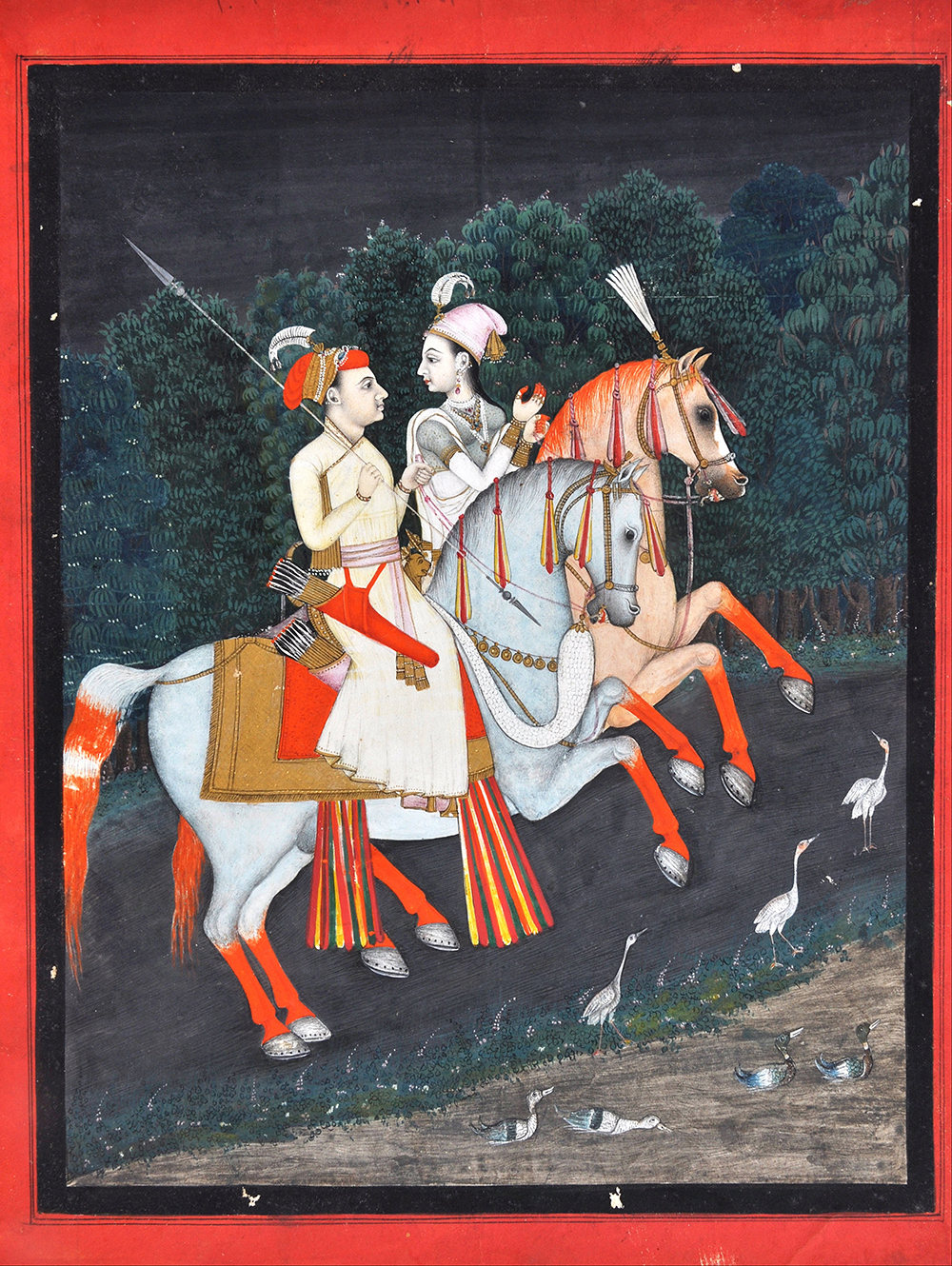

Nautch girls in Mumbai, by Taurines, c. 1880. Wikimedia Commons.

The court of the Mughal emperor Jahangir (1569–1627), who ruled India from 1605 until his death in 1627, gained a particular reputation for its licentiousness as a result of the activities of the “nautch girls.” As part of the entertainment for the royal family, these highly skilled dancers performed for the ruler and entertained his guests. They also formed part of everyday life for those outside the palaces, as people invited them to perform at celebrations, festivals, and fairs. These women were valued for their intelligence as well as their dancing skills and were at least partially educated. As a form of side employment they offered sexual services, and they would cover themselves in gold as an outward sign of their wealth.

The history of the nautch girl goes back as far as the seventh century to the temple dancers witnessed by Chinese Buddhist monk Xuanzang, who had admired the movements of the dancers at the Sun Temple of Multan. The name nautch derives from the Prakrit natcha, meaning “dance,” but the girls had a reputation for connecting sex with their music and dance. Most of them were trained to dance as children; some were slaves, others had been sold by their parents. When a nautch girl lost her virginity, a celebration known as a misi or nath utarwai (nose opening) took place. Every Hindu temple of any importance possessed a troupe of nautch girls: some acted as priestesses, married in childhood to the idols and obliged by their vocation to prostitute themselves to men of every caste; others acted as mistresses to the temple priests. Such prostitution was not looked down on, and even distinguished families were proud to have daughters dedicated to the temple’s service. At one time it was estimated that twelve thousand such temple prostitutes existed in Madras alone.

For the Western travelers, the nautch girls were the embodiment of sexuality, highly erotic seductresses who had the ability to charm all males. Indeed, seventeenth-century travelers frequently portrayed India as a hotbed of vice and full of prostitutes. Other foreign visitors, chaplain of the East India Company John Ovington among them, were more tolerant and appreciative of the dancing girls. He commented admiringly, “The Dancing Wenches, or Quenchenies, entertain you…with their sprightly Motions, and soft charming Aspects, with such amorous Glances, and so taking irresistible a Mien, that…[they] gain an Admiration from all.” Female travelers were less appreciative and castigated the nautch girls for their beguiling ways and their apparent ability to bedazzle men: with rings on their fingers and bells on their anklets, they stomped and gyrated their way into men’s affections. Eighteenth-century visitor Jemima Kindersley complained, “Their languishing glances, wanton smiles, and attitudes [are] not quite consistent with decency.” Their kohled eyes, red-painted nails, and hennaed hands and feet were all considered provocative.

A few decades later, on visiting India, children’s writer Mary Martha Sherwood expressed similar sentiments when she discovered the profound erotic effect these Indian women had on English men. In her memoirs she wrote, “The influence of these Nautch girls over the other sex, even over men who have been bred in England, and who have been known, admired, and respected by their own countrywomen, is not to be accounted for.” The only explanation, it seemed, was that the nautch girls held some mystical spell over the men: “This influence steals upon the senses of those who come within its charmed circle not unlike that of an intoxicating drug, or that of what is written in the wiles of witchcraft, being the more dangerous to the young Europeans because they seldom fear it.” For Sherwood, the nautch girls were veritable temptresses, their advances impossible for men to refuse, writing: “The women had a way with music which drew the enchanted lovers to their lair.” Their singing had a mesmeric effect on the men as they sang night after night, “the song of the unhappy dancing girls, accompanied by the sweet yet melancholy music of the cithera…All these Englishmen who were beguiled by this sweet music…slowly sacrificing themselves to drinking, smoking, want of rest, and the witcheries of the unhappy daughters of heathens and infidels.” There was little doubt: the nautch girls had become a sexual threat to the tight-laced colonial women.

By the end of the nineteenth century, complaints about the nautch girls reached a fever pitch as various newspapers and evangelical pamphlets attacked them for their sexual debauchery. Subodh Patrika, a Bombay journal, carped, “Stripped of all their acquirements, these women are a class of prostitutes, pure and simple. Their profession is immoral and they live by vice.” The Indian Messenger went further, complaining,

We have seen with our own eyes these women introduced into respectable circles in open daylight, and men freely associating with them, while the ladies of the house were watching the scene from a distance as spectators and not taking part in the social pleasures going on before them, in which the dancing girls were the only female participators.

In the northwestern provinces, one author objected that dancing girls were treated with as much courtesy as princesses, and that some of their songs were objectionable and lewd; that precious jewels were given to them and large sums of money squandered on them. Even the governor of Madras had four groups of dancing girls at his garden party. Wives living in the cities complained that they were often forsaken at night for the “cosity of nautch women, trained in all the accomplishments which can effect the ruin of their victims.” The Indian Social Reformer rued, “In large cities, like Madras, I am afraid the general opinion is that a man is not worth his position if he does not attach himself to a dancing girl.”

Meanwhile, the erotic allure of the nautch girl was completely lost on a few solitary folk. Walter Ryland, who was traveling on a tour across the East in 1882 with the aim of improving his health, saw very little to enamor him when he stopped off in Delhi and was invited to watch a nautch girl dancing. At the event, he found himself in the middle of about six or seven hundred men and boys sat four or five deep, with no other women present. Ryland claimed that he found the experience all rather oppressive and dull.

Over time, the dancing girls who had been so admired and celebrated for their skills and attributes in precolonial India saw a decline in their status. During the British colonization of India, the nautch girls fell from their exalted position of esteemed artist to the role of common prostitute; their movements, previously appreciated as high culture, were now seen as merely sexually provocative. This shift in attitude towards the nautch girls is sometimes blamed on the influx of British soldiers of the East India Company, as they took the women as mistresses and gave them little in return.

Reprinted with permission from Licentious Worlds: Sex and Exploitation in Global Empires by Julie Peakman, published by Reaktion Books Ltd. Copyright © 2019 by Julie Peakman. All rights reserved.