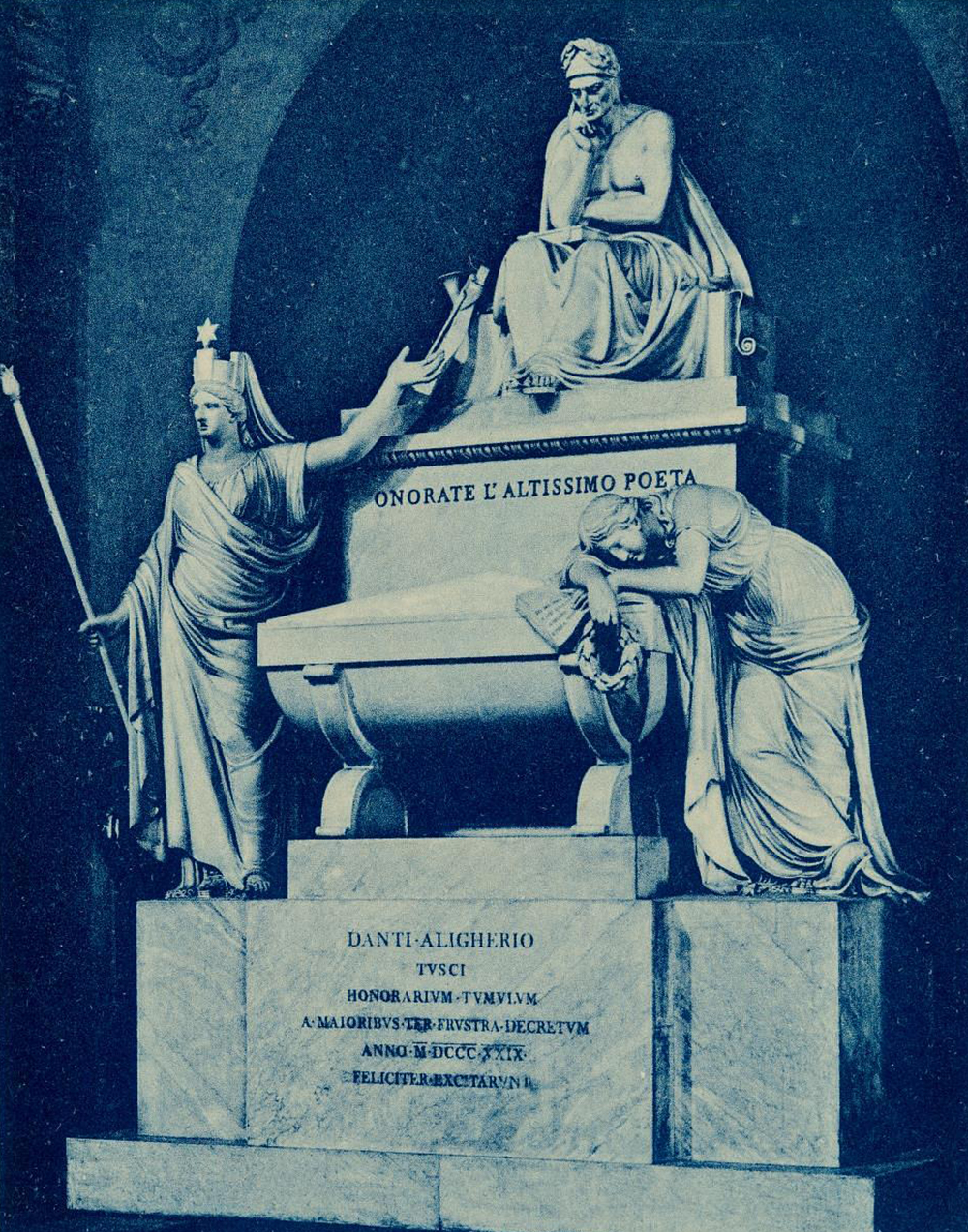

The Tomb of Dante at Ravenna, by Francis Dillon, 1865. Wikimedia Commons.

Quartan malaria, with its dreaded recurrence of chills and high fever every fourth day, claimed an untold number of lives in Italy during the Middle Ages. So familiar were its ominous signs that a fourteenth-century Italian poet seeking to fill readers with bone-quaking fear need only conjure the image of a man who “in a shivering fit of quartan fever, / so ill his nails have lost all color, / trembles all over at the sight of shade.” Dante identified with malaria victims—whose suffering he had seen with his own eyes—to convey his deathly fright at having to fly to a lower circle of hell on the back of Geryon, a monster with an honest-looking human face fronting a serpentine body with leonine paws and a scorpion’s tail. The writer of those words now experienced firsthand the sweats, chills, and aches of the debilitating illness.

He had contracted malaria for real, and it was a literal death sentence. Although early chroniclers and biographers say precious little about Dante’s final days, their accounts, supplemented by contextual documentation, allow for a plausible representation of his illness, death, and burial.

Dante lived his final two decades in exile from Florence because he was a victim of the local and papal politics that roiled Tuscan cities. The factions of his day were the Black Guelphs and the White Guelphs—color-coded labels imported from Pistoia in 1301—headed by, respectively, the aristocrat Corso Donati and the banker Vieri dei Cerchi. Dante climbed the ladder of Florentine governance as a White Guelph, reaching its highest rung when he was elected to the city’s six-member Council of Priors for a two-month term beginning on June 15, 1300. His triumph could not have come at a worse time. “All my woes and all my misfortunes,” he reflected in a letter, “had their cause and origin in my ill-omened election to the priorate.”

Dante’s opposition to Pope Boniface VIII’s campaign to annex Tuscan lands led to troubles the following year. Boniface sent the French prince Charles of Valois to Florence ostensibly as a peacemaker, but really as a military occupier allowing pro-papal Black Guelphs to overthrow the White Guelph government. Dante was one of three Florentines dispatched to meet with Boniface, who flatly rejected their appeal to negotiate. The poet was still in Rome or on his way back to Florence when Charles entered the city on November 1, 1301. Black Guelph mobs soon unleashed a wave of terror against their White Guelph neighbors. Chief Magistrate Cante de’ Gabrielli issued two proclamations naming Dante among those accused of committing various crimes while in office. Because Dante failed to present himself to answer the initial charges, the second proclamation, dated March 10, 1302, sentenced him to death by fire should he “at any time come within the power of the commune.” The poet never set foot again in Florence.

As a political exile, Dante was excluded from a Florentine pardon in 1311, but another amnesty in 1315 would have allowed him to return. Unwilling to comply with terms of the offer—admission of guilt and payment of a fine—Dante was again sentenced to death, this time by beheading rather than fire, the penalty now also applying to his sons Pietro and Jacopo. An additional provision stated that anyone had permission “to harm them in property and person, freely and with impunity.” Dante’s refusal reflected not only his great pride but also better living conditions. He was now residing in Verona as a guest of the Ghibelline ruler Cangrande della Scala. Having cut ties with his native city, he declared himself “Florentine by birth, not by disposition.” Dante had learned how bread outside Florence “tastes of salt,” but by 1316 he could say that such bread “will surely not be lacking.”

Moving to Ravenna under the patronage of Guido Novello da Polenta in 1318—perhaps as late as 1320—improved life even more for the Alighieri family by providing a measure of stability and independence. The poet had his own house in Ravenna, the city in which he found the resources, inspiration, and ambiance conducive to writing the final cantos of the Divine Comedy. No longer a center of political and ecclesiastic power, Ravenna retained an aura of its past grandeur that appealed to Dante at this late stage of his life. Five centuries later, the Irish writer Oscar Wilde likewise imagined Ravenna, a “poet’s city,” as “like Proserpine, with poppy-laden head, / guarding the holy ashes of the dead.” The city’s “lone tombs where rest the Great of Time” inspire “hearts to dream of things sublime.” Ravenna’s deep invocation of the past—what the Dante scholar Giuseppe Mazzotta calls its “posthumous” nature and “dreamy immobility”—meshed perfectly with the medieval poet’s vision of the afterlife as a conversation between the living and the dead.

Dante also contributed to Ravenna’s welfare by participating in diplomatic negotiations, one of which cut short his life. With Ravenna on the brink of war with the Republic of Venice, its powerful neighbor on Italy’s northern Adriatic coast, Guido Novello sent Dante on a diplomatic mission to the Serenissima, hoping that the “eloquence and reputation of the poet might avert impending ruin from him” and bring the conflict to a peaceful resolution.

Venetian records show that the city was indeed preparing for military operations against Ravenna in August 1321, with negotiations to end the crisis beginning soon thereafter.

The casus belli was Ravenna’s capture of Venetian vessels and its killing of a captain and several crewmen (with others injured in the attack). Seeking revenge for the unjustified aggression, Venice called on Forlì to join in waging war as soon as possible against their common enemy and enlisted the support or at least neutrality of Rimini. Grasping the seriousness of this threat to Ravenna, Guido dispatched Dante and other ambassadors to Venice at the end of August.

The land route between Venice and Ravenna posed risks of its own, more so during the time of year when Dante traveled. With the first rains of the season wetting the marshlands, parched after the hot summer months, conditions were ripe for contracting malaria. The rivers, canals, swamps, and lagunas of the region have always made it a fertile haven for mosquito-borne illnesses. By the time Dante returned to Ravenna in early September, the recurring bouts of fever had so weakened him that he died within days.

Following medieval Christian practice, a priest would have administered last rites—confession, communion, and extreme unction—to the dying man at home. Bringing consecrated oil and hosts, he would have heard Dante’s last confession, absolved him of sins, administered last communion food for passage to the afterlife (viaticum)—and anointed his body. The poet’s earthly life ended “in the month of September in the year of Christ 1321, on the day on which the exaltation of the holy cross is celebrated by the Church,” meaning on September 14. Scholars commonly date Dante’s death to the night of September 13–14, 1321. Giovanni Boccaccio gave his illustrious forebear an appropriately literary farewell, writing about his death, “He rendered up to his Creator his toil-worn spirit, which I have no doubt was received into the arms of his most noble Beatrice, with whom, in the sight of Him who is the supreme Good, the miseries of this present life left behind, he now lives most joyously in that life the happiness of which has no end.”

Mourners typically carried the dead body to the church for recitation of the office of the dead and a requiem mass before proceeding to the cemetery for burial. Dante’s funeral probably conformed to this late medieval Christian model but with a few differences in keeping with the poet’s exalted status. Piero Giardino, a friend who said he had been at Dante’s deathbed, was probably also Boccaccio’s source for information on the funeral. Guido Novello da Polenta, who had felt “the greatest grief” at Dante’s death, placed his body, “adorned with poetic insignia, upon a funeral bier, and had it borne on the shoulders of his most distinguished citizens to the place of the Minor Friars in Ravenna, with such honor as he deemed worthy of such a corpse.” After the procession, which was accompanied by “public lamentations,” Guido had Dante’s body “placed in a stone chest, in which he still lies.” He then returned to the poet’s house, where, following Ravennese custom, he “delivered an ornate and long discourse both in commendation of the profound knowledge and virtue of the deceased, and in consolation to his friends, whom he had left in bitterest grief.”

Chronicler Giovanni Villani reiterated the high tribute paid to Dante on his death, noting that he was interred close to the main church “with great honor, in the attire of a poet and of a great philosopher.” One of Dante’s earliest commentators went much further, opining in 1333 that “he received the sort of singular honors not given since the death of Octavian Caesar.” Observing that Dante “still lies” in the simple stone tomb several decades after his death, Boccaccio reported that this was not inevitable. On the contrary, Guido Novello had promised—“if his estate and his life endured”—to honor the poet “with such an excellent tomb that if never another merit of his had made him memorable to those to come, this tomb would have accomplished it.” The Florentine humanist Giannozzo Manetti described Dante’s original tomb in far more generous terms, calling it “a splendid and imposing tomb built of finely hewn square stones,” but the fact remains that over a century after his death, Dante’s bones lay in the same plain sarcophagus in which they had been placed in 1321.

The sort of political conflict that had vexed Dante in life was likewise responsible for Guido’s failure to provide the “excellent tomb” he had said would keep the poet’s memory alive for future generations. The noble ruler’s good intentions came to naught when, during a stay in Bologna soon after Dante’s burial, political enemies (led by a cousin) staged a coup back in Ravenna and Guido was never again able to return to the city. As if intuiting that a physical structure worthy of holding Dante’s bones would be a long time coming (if at all), Boccaccio therefore took it upon himself to build—with words, not stone—the magnificent tomb that Guido had promised, a “monument to Dante,” as one scholar labels the younger writer’s work as editor, biographer, apologist, and commentator on behalf of his illustrious predecessor. “Not indeed a material tomb,” Boccaccio commented on his verbal homage to the poet, it “is nonetheless—as that was to have been—a perpetual preserver of his memory.”

But if words are building blocks, Dante is ultimately his own best tomb maker. Stone—even marble—can seem a flimsy medium in which to memorialize a man whose monumental house of the afterlife immortalizes himself and his characters in verse. Giuseppe Verdi, the renowned composer of opera, drove home this point when asked to contribute to a fund for the construction of a new mausoleum for Dante in the 1890s, a project that never materialized.

“Sir!” Verdi indignantly responded, “put right this unseemly situation, you say? But what situation? Unseemly because I haven’t sent in my offering for the monument to Dante? Dante raised by and for himself a monument so great—and so high—that no one can reach it. Let’s not lower it with displays that place him on the same level as so many others, even the most mediocre. To that name I don’t dare raise hymns: I bow my head and worship in silence.”

In Italian Hours, a collection of astute commentary on Italian locales and monuments, the novelist Henry James expressed similar reverence for Dante at the expense of any monument built to honor him. Underwhelmed by the poet’s tomb in Ravenna—a sight “anything but Dantesque”—James decided that in this case the physical structure mattered little. “Fortunately of all poets he least needs a monument,” the novelist reflected, “as he was preeminently an architect in diction and built himself his temple of fame in verses more solid than Cyclopean block.”

Excerpt adapted from Dante’s Bones: How a Poet Invented Italy by Guy P. Raffa, published by Harvard University Press. Copyright © 2020 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College. Used by permission. All rights reserved.