In 1999 Oxford University Press published Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898, written by Edwin Burrows and myself. In it we addressed topics usually dealt with separately—poetry, sexuality, architecture, banking—and wove them together in an attempt to capture the interactivity that shaped the life of the city in its first centuries. I’ve often thought that by using the index and internet it would be possible for readers to reverse that process and disaggregate the individual threads—the history, say, of Irish New Yorkers, which is treated at many points in the 1,400-page text—and thereby produce a mini history of the selected topic. What I’ve done here is extract from Gotham some descriptions of epidemics unknown to anyone other than specialist historians and reproduce them in chronological sequence.—Mike Wallace

1793

An epidemic of yellow fever battered Philadelphia, and compassionate New Yorkers raised five thousand dollars for the suffering city. There was, however, no agreement on what caused the yellow fever (in fact, the agent was a virus transmitted by the Aedes aegypti mosquito), and in a politicized era the dispute quickly took on political overtones. Federalists tended to depict it as a foreign contagion—the biological counterpart, so to speak, of French Jacobinism. Republicans answered that it was the product of “nauseous stenches” rising up every summer from the city’s “abominably filthy” waterfront and other unsanitary conditions for which only the negligence and incompetence of Federalist magistrates were to blame. Yet etiological positions were not rigid. Many merchants, generally Federalist in their politics, preferred to fault the local environment rather than imported contagions, which could lead to trade-disrupting quarantines. Indeed, virtually every city body that addressed the problem chose to sidestep the controversy by advocating both quarantine and sanitation.

The predominantly Federalist municipal government established a semiautonomous Health Committee, composed of aldermen and citizen volunteers, which cut off communications with Philadelphia, presumed source of the pestilence. Committee inspectors patrolled the waterfront with full power to turn away or quarantine persons as well as goods arriving from that city. In close conjunction with these efforts, the committee also set out to track down “nuisances in this city,” such as the “dead horses, dogs, cats, and other dead animals lying about in such abundance, as if the inhabitants accounted the stench arising from putrid carcasses a delicious perfume,” as one letter to an editor put it sardonically.

Governor George Clinton officially instituted the Health Committee in 1794. The group in turn got the Common Council to lease Bellevue, a rustic estate owned by Quaker merchant Lindley Murray that overlooked the East River north of the settled city, for the use of fever victims.

In 1795 yellow fever was reported to be widespread in the West Indies. Early summer, while hot and humid, passed uneventfully, though Dr. Valentine Seaman noticed (without understanding the significance of his observation) that “mosquitoes were never before known, by the oldest inhabitants, to have been so numerous as at this season, especially in the southeastern part of the city.”

In mid-July, the health officer was summoned to attend three sick seamen aboard a vessel in the East River. He caught the disease and died eight days later. More cases surfaced on the waterfront. The Health Committee denied any occasion for alarm, but many wealthy men sent their families out of town in August. Then the number of cases shot upward, touching off a mass September exodus. Well-to-do residents shuttered their businesses and decamped for Greenwich, Harlem, and other nearby country villages, leaving thousands of unemployed mechanics and laborers to fend for themselves. Health Committee members made daily rounds, giving medical treatment, distributing relief, and sending victims up to Bellevue.

The fever burned on through October until cool weather brought a sharp reduction in mortality, but by then the epidemic had claimed a record 732 victims—and had proved, according to Mayor Richard Varick, “most fatal among the poor emigrants, who lived and died in filth and dirt.”

1798

Amid frantic preparations for war with France, the fever slammed into New York with greater fury than ever. The first cases came to light at the end of July, again in the dock areas by the East River. Within weeks every resident able to do so had fled. Left behind were the poor and dependent, many made destitute by the death or incapacity of the household wage-earner.

The doctors of New York remained on the job—twenty of them falling victim to the fever—while the new state health commissioners, aided by zealous watchmen, carted the sick up to Bellevue and established three “cook houses” where the poor were given soup, boiled meat, and bread. At the peak of the epidemic in September and October, sixteen hundred to two thousand were fed each day, and another eight hundred at the almshouse, the cost covered by Common Council appropriations and donations from wealthy merchants and other towns.

A Warren Street carpenter, trying to keep up with the demand for coffins, hired two little boys to hawk the pine boxes around town on a hand wagon. Stopping at intersections, they sang out, “Coffins! Coffins of all sizes!”

When the crisis finally passed, the disease had claimed 2,086 lives—close to 5 percent of the population. While a number of prominent citizens lay dead, the great majority of victims, as in previous epidemics, were poor. Many were buried in the new potter’s field, just opened in 1797, to the north of town on the site of today’s Washington Square.

Shaken by this catastrophe, the Common Council established a committee to investigate its causes. Their report, made public in 1799, came down hard on unsanitary conditions, attributing the disease to “filthy sunken yards” filled with offal, putrefying matter in pools of stagnant water, damp cellars, foul slips, decayed docks, open sewers, and overflowing privies. The report called for sweeping reforms, which it admitted would inconvenience and abridge the property rights of citizens. But the public welfare came before individual rights, the committee concluded, and the Common Council should have “great and strong power, to clean up the city.”

The Common Council drafted a bill for the legislature embodying virtually all the recommendations. The legislature enacted it promptly, and in the next few years municipal authorities would embark on a series of unprecedented interventions in hitherto private affairs. (The state also passed a new quarantine act in 1799 and built a quarantine station on Staten Island, at Tompkinsville. By 1800 the first buildings of the new Marine Hospital were ready to receive fever victims and to accommodate sick passengers removed from incoming vessels.)

1803

While these initiatives were underway, fever flare-ups remained mild until the summer of 1803, when again, one physician wrote, “the wealthy early abandoned the city, and the poor are daily falling victims to its ravages.” The state-appointed Health Commission did excellent work, but in the wake of this latest epidemic the Common Council decided to establish its own Board of Health, to be headed by Mayor De Witt Clinton. The legislature agreed and ceded all powers to the new body, including the authority to order any vessel into quarantine.

The city supplemented the new Board of Health with an even more novel office, that of City Inspector. Its mission would be to gather information about public nuisances and propose ordinances to “remove or correct” them, in order to ensure “the future health of the City.”

After 1805 yellow fever disappeared from New York for fourteen years. While this probably had more to do with a parallel decline of the disease in the West Indies, it was due in part to the burst of municipal action triggered by the disaster of 1798, above all a drainage campaign that might have reduced, albeit inadvertently, breeding places for mosquitoes.

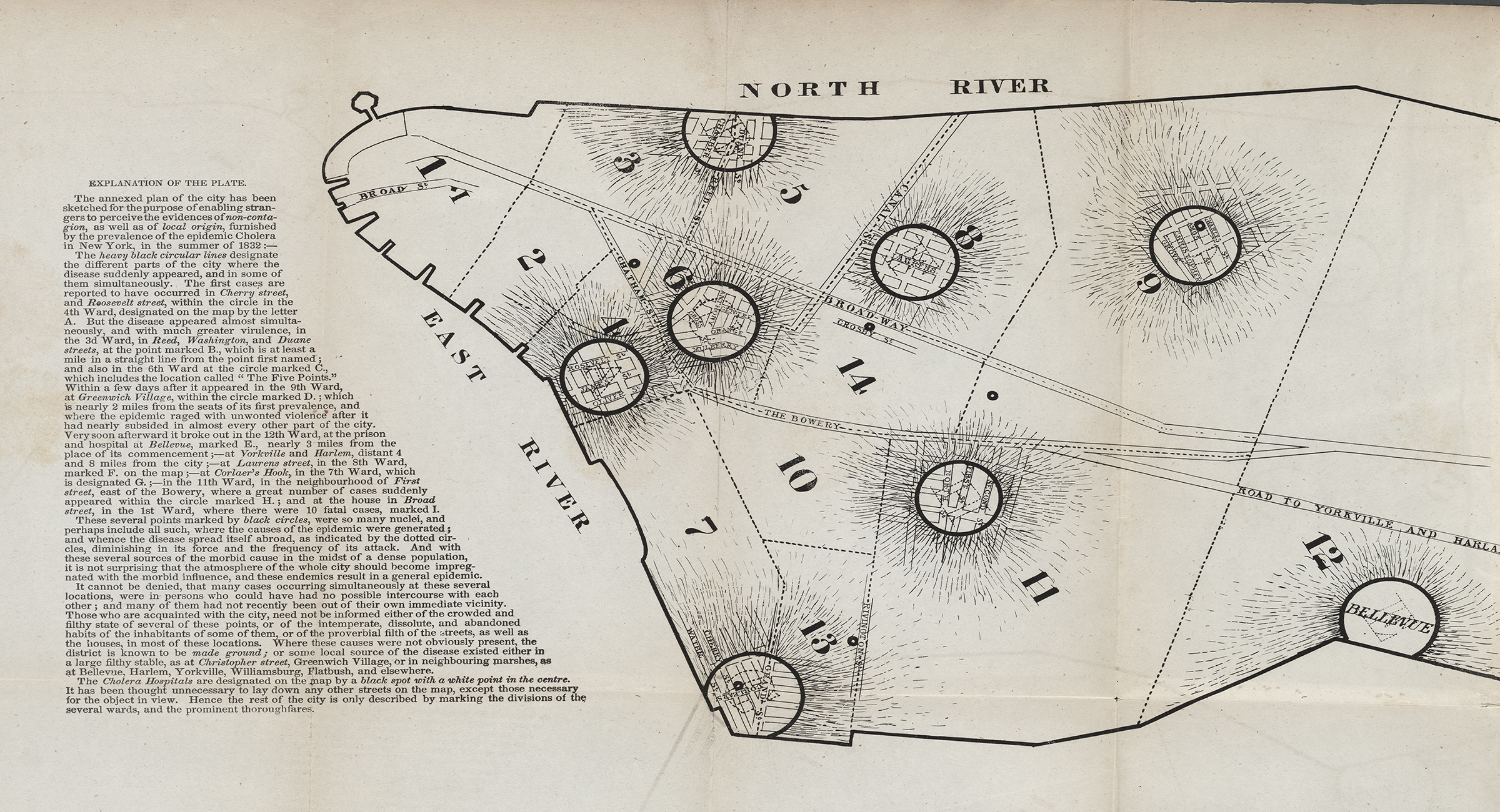

1832

The cholera roared into town. New Yorkers had seen it coming. They had read in their papers of its devastating march across Asia and the trade routes to Europe, reaching Poland, then France, then England. City authorities knew the plague might well ride the sea lanes to the Hudson but did next to nothing with this foreknowledge.

New York’s old Board of Health certainly had authority to act. Yet it had been lulled into quiescence in the ten years since the yellow fever epidemic of 1822. Its approach to disease prevention, moreover, now concentrated almost exclusively on quarantining ships from dangerous southern waters. Even there, it was under constant pressure not to render too hasty a diagnosis that would cut off the flow of trade and profit. The board, one critic noted caustically, was “more afraid of the merchants than of lying.”

As spring turned to summer, the Medical Society, which represented two-thirds of the city’s licensed physicians, urged immediate cleaning of streets, yards, and vacant lots; disinfection of privies and cesspools with quicklime; and establishment of a network of emergency hospitals. The city administration responded with an apathy partly rooted in the conviction—widely shared, but advanced most ardently by evangelical clergymen—that the plague, should it come, would pass over the virtuous parts of town and descend, like God’s wrath, on its sin-infested quarters. Ministers told the pious that the path of righteousness was the road to health. Temperance activists plastered Manhattan’s walls with notices like quit dram drinking if you would not have the cholera.

Physicians’ belief in “predisposing causes” also suggested the likeliest victims would be those who, through indulgence in vice, intemperance, and filthy living habits, had weakened and predisposed themselves to the disease. Science and religion thus sailed on parallel courses, with their essential interconnections drawn out most clearly by Sylvester Graham, who lectured that liquor, impure foods, and sexual dissipation undermined the body’s ability to resist the cholera. Bons vivants ridiculed the Grahamites and advised citizens to fortify themselves with a hearty diet of meat, spices, and brandy.

On June 15 the Albany steamboat brought word that the cholera had forded the Atlantic, wreaking havoc in Quebec and Montreal. By June 18 it was reported at Ogdensburg. New York City mayor Walter Bowne proclaimed a severe quarantine. No ship was to approach closer than three hundred yards to the city, no land-based vehicle to come within a mile and a half. The Courier and Enquirer printed a cholera extra of ten thousand copies. Apothecaries posted handbills advertising opium, camphor, and laudanum.

On June 20 a large group of clergy and prominent laymen met at the American Bible Society and called for a day of fasting and prayer. They were seconded by the Common Council, but workingmen’s advocate and freethinking editor George Henry Evans urged his readers to ignore the recommendation as an “insidious and dangerous encroachment” on the separation of church and state.

Late Monday night, June 26, an Irish immigrant named Fitzgerald came home violently ill; he recovered, only to have two of his children die after being struck by the identical agonizing stomach cramps. The city fathers pressured the Board of Health into declaring them the victims of nothing worse than diarrhea, a common summer complaint. But many physicians had seen and diagnosed cholera, and beneath the blanket of official silence, word spread fast.

Methodists began prayer meetings each morning. June 29, the Day of the Christian Martyr, spent in fasting and humiliation, was observed in scores of churches. The Medical Society, fed up with the dilatory Board of Health, stated publicly on July 2 that cholera had struck nine people and that only one had survived. John Pintard, founder of the New-York Historical Society, attacked this “impertinent interference” with the constituted authorities and asked if the doctors knew the disaster their announcement would wreak on the city’s business.

On July 3 the Evening Post reported that a great exodus had begun. For all the certainty about their moral and physiological invulnerability, the city’s comfortable classes weren’t about to stake their lives on it. The roads were lined with “well-filled stage coaches, livery coaches, private vehicles, and equestrians, all panic struck, fleeing from the city, as we may suppose the inhabitants of Pompeii or Reggio fled from those devoted places, when the red lava showered down upon their houses.”

Oceans of pedestrians trudged outward with packs on backs. Steamboats bore refugees up the Hudson. Every farmhouse and country home within a thirty-mile radius was soon filled with lodgers. By the end of the first week in July, almost all who could afford to flee had fled; by the Post’s estimate of August 6, that figure eventually reached 100,000, roughly half the city’s population.

Of the other half, 3,513 died, most of them horribly, the lucky ones swiftly. The young editor Henry Dana Ward wrote his parents that some “are taken like lightning from the midst of their families and daily work.” One paper reported smugly that a prostitute who had been adorning herself before her glass at one was in a hearse by half past three.

Cartloads of coffins rumbled through the streets but couldn’t keep up with demand. One day the Presbyterian evangelist Charles Grandison Finney noticed five hearses drawn up at five different houses, all at the same time, all within sight of his door. In other neighborhoods, dead bodies lay unburied in the gutters. At the potters’ field, putrefying corpses lay in shallow pits, the prey of rats.

As the city reeled, some sought to calm hysteria among the better-off still in town or camped nearby by noting that, as predicted, the plague was mainly scything the poor.

John Pintard, observing that the plague was “almost exclusively confined to the lower classes of intemperate dissolute & filthy people huddled together like swine in their polluted habitations,” drew the terrible conclusion that the sooner this “scum of the city” was dispatched, the sooner the fever, deprived of fodder, would pass. Most New Yorkers who stayed in town, however, sprang into action in an effort to succor or rescue plague victims, sinners or no. The Board of Health assumed governmental functions. Streets, lots, cellars, and docks were cleaned of a decade’s accumulation of filth and strewn with lime. The clothes and bedding of the sick were taken out and burned, the fumes filling the air.

With thousands of wage earners thrown out of work by the abrupt cessation of the city’s business, private citizens and churches established a Committee of the Benevolent. A July 16 meeting at the Merchants’ Exchange collected about seventeen hundred dollars for poor relief; thousands more dollars flowed from prominent merchants. The committee divided into fifteen subcommittees, one for each ward. These groups paid local residents for “cleansing and purifying their own dwellings,” established soup kitchens, and distributed food and clothing. This was hands-on charity.

For some, the poor swam into focus for the first time. At the height of the epidemic Mrs. P. Roosevelt noted that while ordinarily “no one notices the poor” who “frequently are to be found lying in the streets,” now they were being “picked up and taken to the hospitals.” “Only on occasions such as this,” she reflected, “is the true extent of the misery of the city known.”

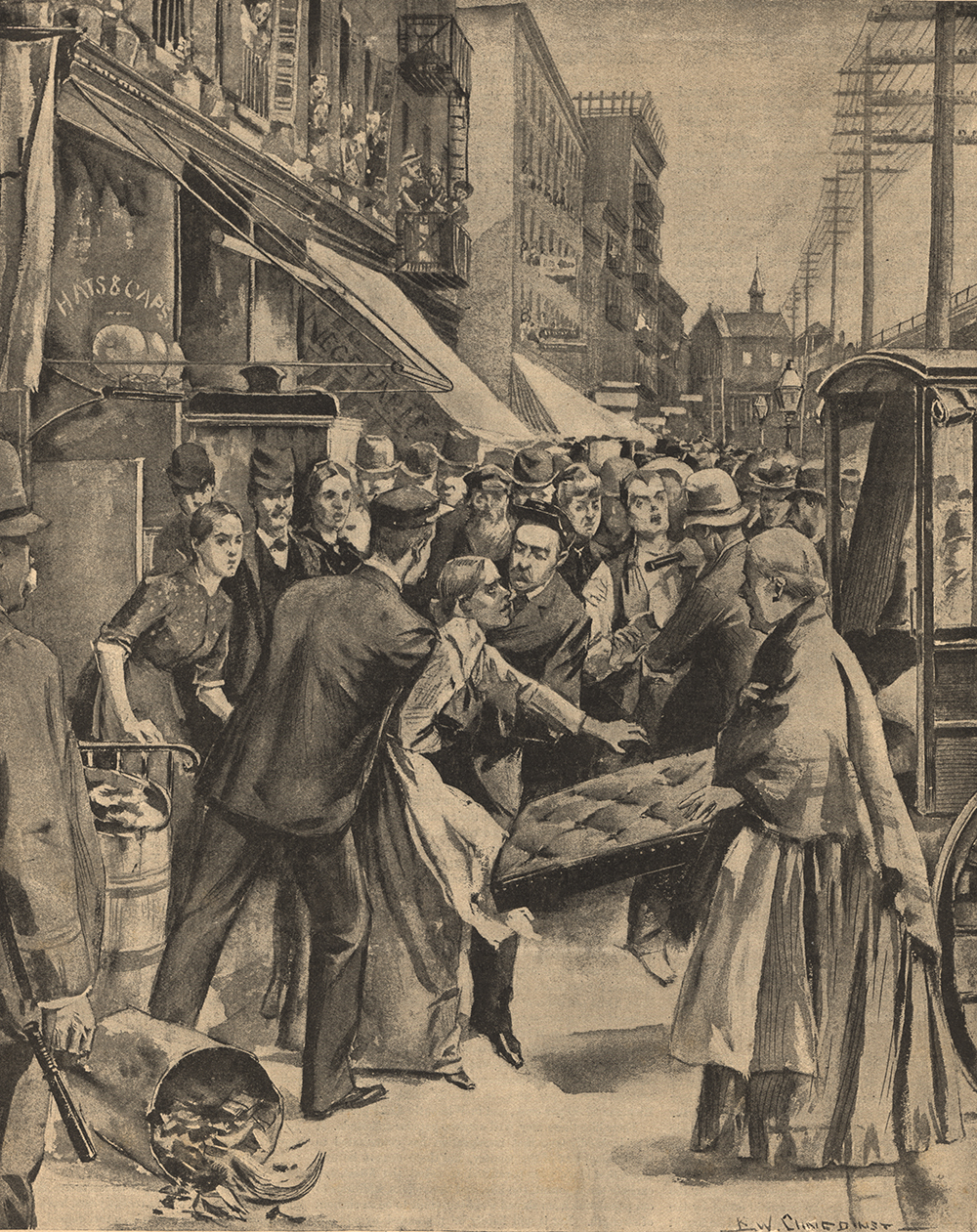

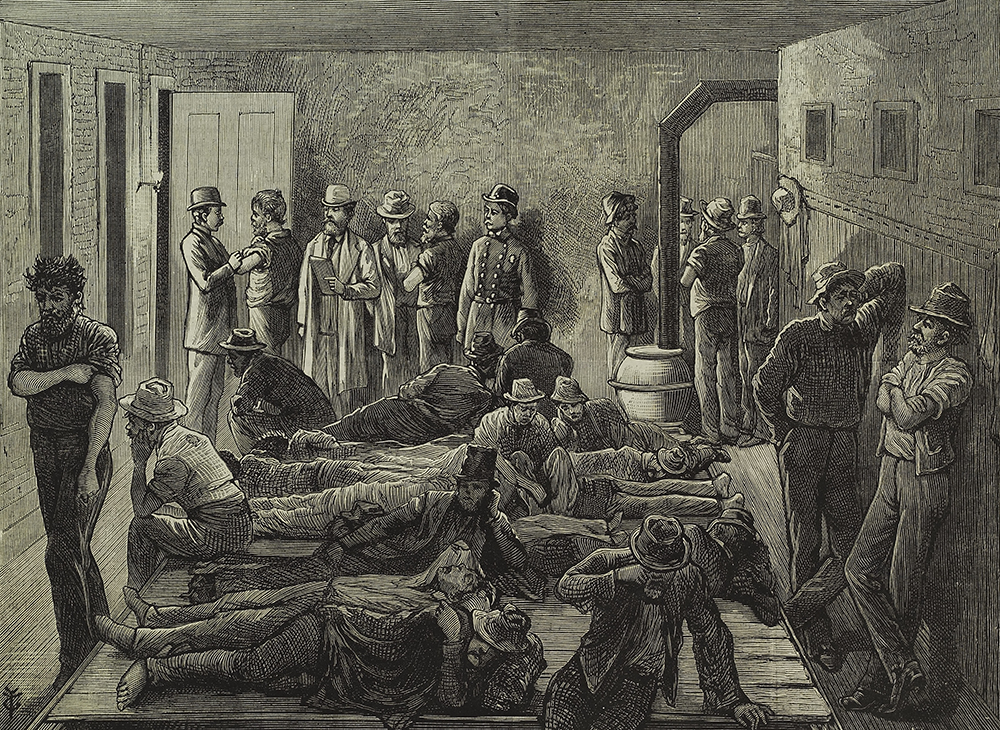

To supplement its work, the Board of Health established five cholera hospitals around the city—in the Hall of Records, a school, an old bank, an abandoned work shed, and a workshop at Corlear’s Hook (the arrival of the latter precipitating a mass exodus of workers from adjoining shipyards). Most poor people forcibly blocked efforts to remove their sick to these hospitals, regarding them as charnel houses run by incompetents. Doctors and city officials who insisted were attacked and brutally beaten.

Following precedents from earlier battles against yellow fever, the authorities set out to disperse the deadly concentrations in the slums. A Committee to Provide Suitable Accommodations for the Destitute Poor evacuated tenants, over the protests of anguished landlords. It moved them to buildings and shanties around town (including one at 10th Street and Avenue C for “colored people in health”), which they leased from other landlords, often at extortionate rents. It then arranged with the commissioners of the almshouse to supply food, medicines, and clothing. The Court of General Sessions discharged all prisoners convicted of misdemeanors and removed felons from the penitentiary and Bridewell to temporary shelter at Blackwell’s Island.

By the third week in July, with the epidemic at its height, great swaths of the city were deathly silent, their streets deserted. Then it ended. Moving on almost as rapidly as it had blown in, the cholera continued its journey along the trade routes, through the Erie Canal towns of western New York, down the Ohio Canal to the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers, tracing the pathways of the market economy with a finger of death.

In August the number of new cases began a steady decline. By the second half of the month, refugees began to trickle back. On August 29 medical authorities pronounced the city safe. Pintard was thrilled at the commercial resurrection. All was “life & bustle,” he rejoiced, with stores all open, sidewalks lined with bales and boxes, streets crowded with carts, and “clerks busy in making out bills.” Beneath his notice, hundreds of beggars, vast numbers of them newly orphaned children, plied the streets. Benevolent ladies started up a Brooklyn Orphan Asylum to deal with the youthful survivors.

Stocktaking in the aftermath generally followed the lines of prior opinion. The Reverend Gardiner Spring saw in the pestilence “the hand of God,” with His sanitary and salutary purpose apparently having been “to drain off the filth and scum which contaminate and defile human society.” Sabbatarians declared the disease “owing to vices which a proper regard to the Sabbath would check more effectually than anything else.” Others blamed drink and slovenliness, including the governor of New York, who opined that “an infinitely wise and just God has seen fit to employ pestilence as one means of scourging the human race for their sins, and it seems to be an appropriate one for the sins of uncleanliness and intemperance.”

The immigrant poor, who had fared worst, came in for the greatest opprobrium. The Board of Health reported that “the low Irish suffered the most, being exceedingly dirty in their habits, much addicted to intemperance and crowded together into the worst portions of the city.” They were poor—due, of course, to their own idleness and fondness for drink—and poverty was the “natural parent of disease.” Philip Hone brought a more succinctly brutal indictment: “They have brought the cholera this year, and they will always bring wretchedness and want.”

Radicals insisted cholera was the result not of divine intervention but of human injustice. “It may be heretical,” said George Henry Evans, “but we firmly believe that the cholera so far from being a scourge of the Almighty is a scourge which mankind have brought upon themselves by their own bad arrangements which produce poverty among many, while abundance is in existence for all.” Certainly there was a correlation between poverty and mortality. But poverty was not a moral failing, Evans wrote that August in the Workingman’s Advocate; it was “occasioned by unjust remuneration of labor.” He urged New Yorkers to impose a graduated income tax that would secure funds from the wealthy to make recurrence of the disease impossible.

1842

John H. Griscom, a learned and pious Quaker physician who served on the Association for Improving the Condition of the Poor’s first executive committee, issued a scorching report on sanitary conditions in the city. Griscom had seen the effects of living in cellars and tenements close up during his years of service at the New York Dispensary and New York Hospital, and after he was appointed to John Pintard’s old post of city inspector in 1842, he embarked on a comprehensive survey of city health.

Griscom concluded that a good deal of metropolitan mortality was avoidable. To his mind, “first among the most serious causes of disordered general health” was the city’s crowded and poorly ventilated housing, especially its rear courts and cellars (he found some that housed as many as forty-eight persons), and he bitterly condemned the cupidity of those who had taken advantage of abject destitution to convert their basements “into living graves for human beings.” Griscom’s second-ranked killer was the omnipresent filth, which resulted from obscenely overused facilities (often fifty people shared a single privy) and from abysmal drainage and sewerage.

After carefully demonstrating the connection between unsanitary living conditions and poor health, Griscom argued for preventive action. Like his predecessors, he wanted common nuisances eliminated. But he went farther, citing studies of Edwin Chadwick and other English health reformers, and urged construction of a comprehensive sewage and drainage system and free provision of Croton water to the entire population.

Griscom also sought public regulation of housing. Going far beyond the existing fire-related statutes, he asked for legislation to protect residents “from the pernicious influence of badly arranged houses and apartments.” Griscom wanted to require landlords to provide tenants with adequate space and fresh air (at least ten cubic feet per minute per adult). He urged banning the use of cellars, limiting the number of residents per building, and holding landlords accountable for keeping buildings clean. To ensure compliance, he proposed replacing politically appointed health wardens with nonpolitical medical experts—a Health Police, authorized to make routine inspections and, if necessary, close down places found unfit for human habitation.

The aldermen did not take kindly to Griscom’s proposals, which among other things would lop off lots of patronage positions, and the doctor was not reappointed as city inspector. But a group of reformers, including Peter Cooper, put together a fund to publish an expanded version of his 1842 study, and The Sanitary Condition of the Laboring Population of New York—a landmark in the history of public health—came out in 1845.

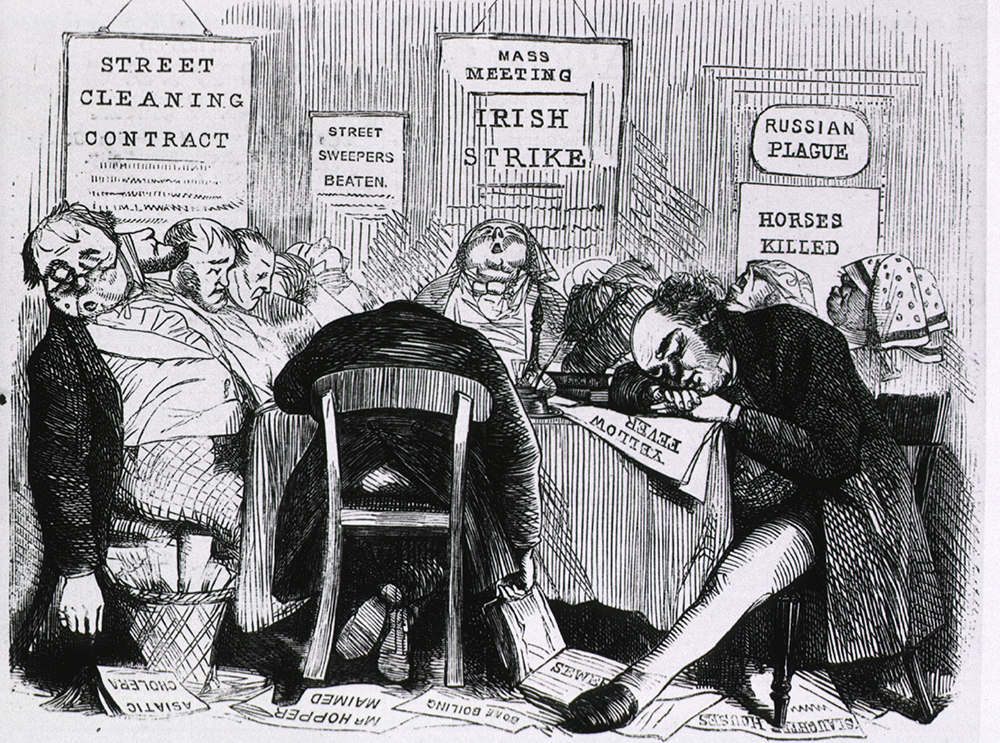

1885

Dr. Hermann Biggs, who had studied at Bellevue Hospital Medical College and in German laboratories, was running Bellevue’s new Carnegie Lab, working as the hospital’s (and city’s) pathologist, and serving as visiting physician at the workhouse and almshouse while maintaining a sizable private practice.

In 1889, after reviewing the work of German bacteriologist Robert Koch, Biggs wrote a landmark report for the Health Department concluding that tuberculosis was communicable and thus preventable. As the disease was acquired by direct transmission of bacilli, usually by dried and pulverized sputum floating dustlike in air, regular disinfection of wards and houses with tubercular patients, as well as rigorous inspections of the city’s meat and milk supply, might make serious inroads against a disease that killed more than six thousand New Yorkers each year but was largely ignored because it was endemic rather than epidemic. Many doctors resisted this view, however, and by the early 1890s virtually the only health workers acting on the theory were the women at the Nurses’ Settlement.

Biggs hammered away at the idea that given Koch’s and French chemist Louis Pasteur’s breakthroughs in microbiology, and the new ability to isolate infectious organisms, “public health is purchasable.” The city could, within natural limits, determine its own death rate.

New York authorities were slow to react until the summer of 1892, when cholera again stalked its way westward from Persia and Russia to the ports of Europe. By August it reached Hamburg, killing thousands. On August 30 the steamship Moravia arrived in New York. Twenty-two passengers had died en route. Ten days later another steamer reported thirty-two deaths at sea.

Now—in addition to imposing a rigorous quarantine, readying a floating hospital, and placing a corps of physicians and nurses on alert—the Health Department established a Division of Pathology, Bacteriology, and Disinfection under the direction of Dr. Biggs. When the disease struck, his laboratory examined the feces of suspected infectees for traces of the cholera spirillum, confirming or denying questionable diagnoses.

Once a case was confirmed in the lab, Health Department crews were dispatched to the lodgings of the stricken, which were scrubbed and fumigated, and the patient’s clothes and bedding treated or burned. The department also marched a small army into the tenement districts to clean streets and vacant lots, scour 39,000 tenements, flush water pipes with disinfectant, and pass out circulars on prevention and treatment in English, German, French, Spanish, Italian, and Yiddish.

Only nine people died. The epidemic—which had killed 2,500 a day in Russia for weeks at a time—had been completely defeated. Never again would this particular scourge gain a foothold in New York City.

But the mobilization was even more significant for what it kicked off: a series of pioneering municipal efforts at preventive medicine. Biggs declared war on diphtheria, a massive child killer whose victims often died a lingering death from suffocation. Using new methods of diagnosis he proved that nearly half the cases thought to be diphtheria weren’t—a crucial discovery, because quarantining such patients with the really diseased could kill them. Biggs now established a system of mass diagnosis. The division supplied culture tubes free and picked them up by messenger each evening; doctors could phone the lab next day for results.

Biggs, while in Europe in 1894, learned of a new diphtheria antitoxin. Using first his own money, then proceeds from a Herald fund drive, and finally a substantial appropriation from the Board of Estimate, Biggs began producing the antitoxin from horses; he was the first to do so outside Europe. The antitoxin halted an epidemic at the New York Infant Asylum in 1895. Biggs began giving it away free to doctors for use with poor patients and sold the surplus to drugstores to fund continued research. The serum brought an immediate and sharp decline in mortality rates, gaining an international reputation for New York City’s Health Department.

Biggs also won acceptance for a more aggressive campaign against tuberculosis. The Health Department put out multilingual educational leaflets. It launched an anti-spitting campaign, instituted inspections for tubercular meat, and required dispensaries and public institutions to report the names of patients with TB, and requested doctors do so voluntarily. It was the beginning of a drive that in ensuing years would eliminate the “great white plague” as a major cause of death in New York City.

Adapted from Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898 by Edwin G. Burrows and Mike Wallace. Copyright © 1998 by Edwin G. Burrows and Mike Wallace and published by Oxford University Press. All rights reserved.