Escape, by Jacob Lawrence, 1967. Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of the Sara Roby Foundation.

“My name is Fountain Hughes. I was born in Charlottesville, Virginia. My grandfather belonged to Thomas Jefferson.” Hermond Norwood recorded his interview with “Uncle Fountain,” as he calls him, in Baltimore, Maryland, in 1949 as part of the Works Progress Administration (WPA) program. There’s a pause after he introduces himself and you can hear the sound of dishes clinking together over the soft hiss of the recording. There’s an occasional car horn and squeak of a chair. Hughes lectures him about the dangers of debt and how at the age of 101 he doesn’t owe anyone anything. “Don’t spend your money before you get it. So many colored people head over heels in debt.” Norwood asks him how far back he can remember, and he says, “Things come to me in spells. I remember things more when I’m laying down than when I’m walking around.” He begins another train of thought about children’s shoes and how he didn’t have a pair of until he was twelve years old. Norwood asks him who he worked for and he responds, “You mean when I was a slave?” He talks about the slaves on the auction block being bought and sold like cattle, about his master not being too bad. He talks about trying to survive after they were freed, sleeping wherever they could, let loose into the world with no money, no education, and no home. His voice is softer, sadder, and while I want to know more, I miss the passion and vigor he had when was talking about fiscal responsibility. The recording is clear, the voice loud, the fidelity is better than the last conference call I had on my cell phone. While he may be long dead, Fountain Hughes sounds like he was right here, right now, and I’m reminded again that there are only few generations between me and Monticello.

Thomas Jefferson inherited his first thirty slaves from his father (he’d own 607 over his lifetime), the same year Horace Walpole published The Castle of Otranto. In 1764 the rumblings of the Revolution were just beginning, but America and England were still about forty years away from ending the slave trade (it lingered longer in Brazil and Cuba). In 1818 Mary Shelley released her modern Prometheus to the world, John Polidori was about to introduce us to our first gentleman vampire, and Frederick Douglass was born into slavery. The narratives that inform our language of terror were beginning to take shape while the seeds of a homegrown American gothic were beginning to take root.

In the discourse about the slave trade there are few words that encapsulate the origins of America better than “horror.” According to Ann Radcliffe, the defining attribute of horror is the “unambiguous display of atrocity.” She was making a critique on the literary works of her gothic contemporaries, but I can’t think of a better way to express the slave trade.

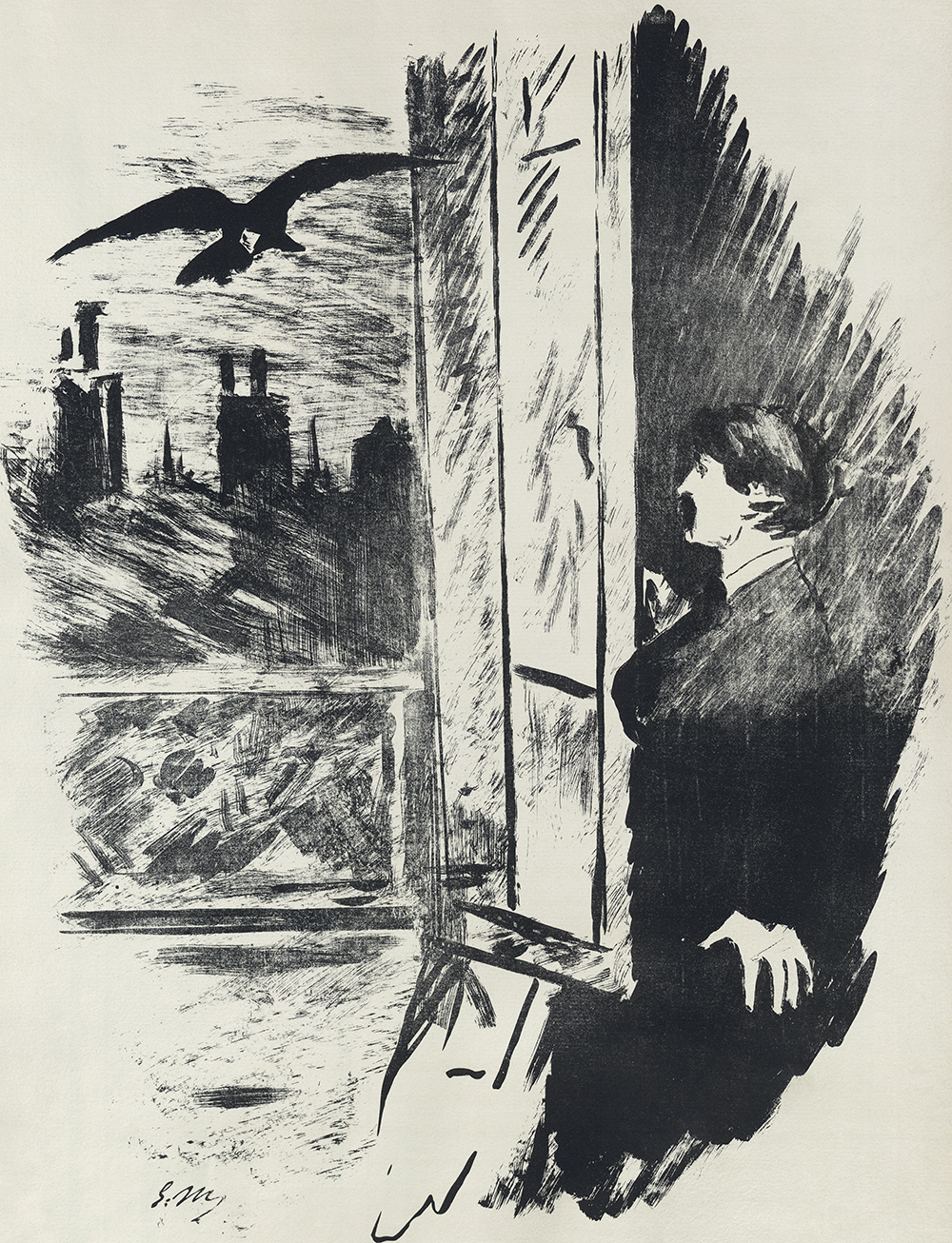

Blackness in America is still in the middle, residing in the place between opposites: living in the present while carrying the past, being human but perceived as other, considered both a person and a product, both American and foreign, neither here nor there. Most gothic tales start with a journey: Shelley’s Frankenstein is an epistolary tale that begins with a journey at sea. There is something almost bureaucratic about Stoker’s Dracula as Harker details the minutiae of his business trip abroad. Portions of Radcliffe’s The Mysteries of Udolpho read like a travel blog as the heroine describes the scenic view from her carriage of the hills of Italy. Whether it is crossing the threshold into a haunted house or crossing the Atlantic, all horror stories starts with a lacuna, the nothingness of the space between places.

In these stories characters are taken out of the comfort and control of their environment (usually voluntarily) and inserted into an alien atmosphere with unfamiliar customs, locations, and languages. It’s a powerlessness that parallels the forced displacement of captive Africans caught in a psychic Bermuda triangle between Africa, the Caribbean, and America. For those who survived, it must have felt like a living purgatory, something in between life and death, here and there, the known and the unknown. Limbo is supposed to be a space of waiting, something in between heaven and hell. But limbo also represents a state of oblivion and nothingness. It’s both a transition and a place of imprisonment, a home for the disappeared.

The Middle Passage was a “non-place,” a space of dread, not only in between land and languages, but between perceptions of the world and states of being. It was a dislocation from one’s history, culture, identity, and autonomy, a horrifying liminality between the familiar old to the terrifying new. The journey through the trade route from Europe to Africa to the Americas and West Indies could last anywhere from one to three months, during which hundreds of Africans were packed into the hull of ships, chained next to people whose language they didn’t speak, sitting in their own waste in sweltering heat and stifling air. Some succumbed to dysentery, dehydration, malnutrition, some refused to eat in despair, some threw themselves overboard, risking the chance of a punishing afterlife for the possibility of returning home to their ancestors.

At the United Nations headquarters in New York City, a memorial was installed marking the (less than elegantly named) International Day of Remembrance of the Victims of Slavery and the Transatlantic Slave Trade. The memorial The Ark of Return is designed by Rodney Leon, an American architect of Haitian descent, and part of the memorial features a figure of a man lying on his back carved from black Zimbabwean granite, wrapped in cloth of white marble. He’s not reclining comfortably, his right arm is stretched out, his neck straining to keep his head raised, a position suggesting that of a slave pressed into in the hold of a ship, barely able to move but still reaching upward. Unlike the still flat figure of the memorialized dead carved into funeral tombs, this figure is either refusing to succumb or is attempting to rise. The intent of the sculpture is to “to psychologically and spiritually transport visitors to a place where acknowledgment, education, reflection, and healing can take place,” but there is something tragic about this figure. He lies in a tomb-like angular structure evocative of a ship, he is reaching up just slightly, his head is lifted but is frozen solid to the marble. The posture suggests a state of paralysis, trying to wake from a dream but unable to rise. He is not yet dead but trapped in memoriam.

Part of the horror of these deaths along the Middle Passage is the lack of memorialization; these are the unknown, the unnamed, lives that are disappeared under duress, deaths destined for haunting. Theirs are stories we will never hear from, people we will never know lost in the Tomb of the Unknown that is the Atlantic Ocean. When we think of haunted spaces, we think of structures or defined areas with clear borders. Can the sea be haunted? How does a ghost inhabit that which has no borders, something formless that ebbs and flows?

There exists a particularly American unease, a lingering creepy aura from the darkness of its foundation. There’s a reason why horror movies keep using the old tired trope of haunted houses built on “ancient Indian burial ground.” America is built over the bones of brown people who were here first and built by black people brought here against their will, and the fear of retaliation is real. But more than that, there is the persistent self-delusion that our gains are not ill-gotten. No one is denying that slavery existed—it just wasn’t that bad, and it was so long ago and we should be over it by now.

The gothic is a retrograde form of romanticism, but America is a forward-looking country, a Manifest Destiny projection to some idealized point in the horizon, and we do not like to be reminded of the sordid path we’ve taken on the way there. I wish there was a word or phrase that named this particularly American anxiety, the unsettled unease of knowing that at any moment the jig may be up.

We need a phrase of our own for the muffled heartbeat under the floorboards, the fetid goo oozing from the walls, the screams coming from behind the wall, the festering guilt that comes with getting away with murder. What is the word then for the fear of exposure, a phrase that represents a fear of accountability? The colloquialism “skeleton in the closet” is the closest I have come, and it has a telling origin going back to 1816 in a British journal on hereditary diseases:

Men seem afraid of enquiring after truth; cautions on cautions are multiplied, to conceal the skeleton in the closet or to prevent its escape.

We use it to describe a secret, a hidden fact that if exposed could have damaging repercussions, the dirty truth that stains something perceived as clean and good. It has a pastiche of horror, a corpse stashed away and left to rot until there’s nothing left but bones. Another version of “skeleton in the closet” used in the late nineteenth century was “a nigger in the woodpile.” It was originally meant as a reference to the Underground Railroad and the practice of hiding fugitive slaves under piles of firewood. The source of that festering corruption was the slave, the original skeleton.

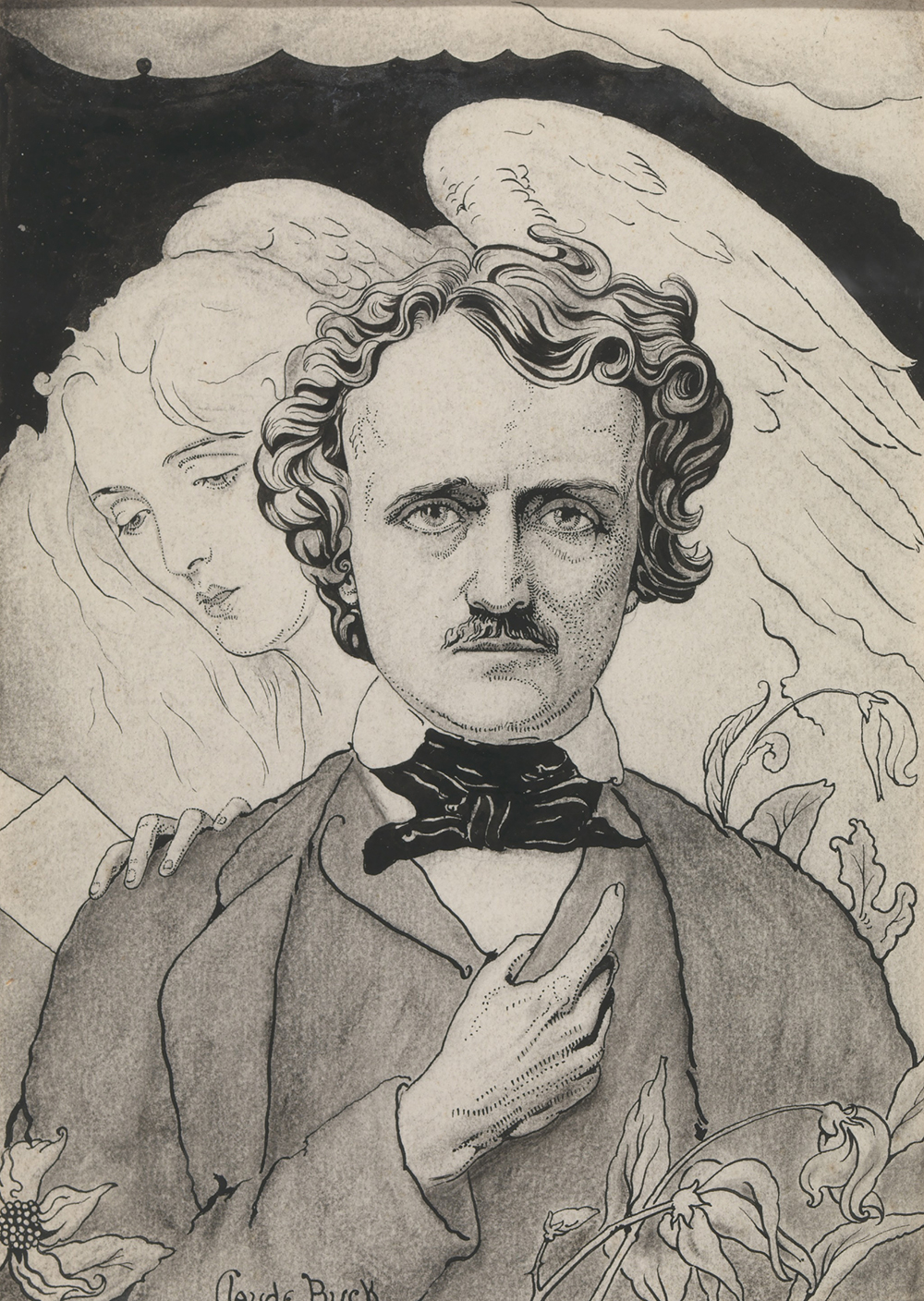

If there was a patron saint for the American gothic, it would be Edgar Allan Poe. “The Pit and the Pendulum,” “The Tell-Tale Heart,” “The Fall of the House of Usher,” and of course “The Raven” are standards of the American literary genre as much as Mark Twain or Walt Whitman. Poe’s floppy black hair, broad forehead, and sunken eyes have graced T-shirts, posters, tote bags, coffee mugs, and greeting cards, and I myself have a Poe action figure on my desk.

In the South Park episode “Dawn of the Posers,” the Goth kids create an unlikely alliance with the Vampire kids against the growing proliferation of Emos. In an ultimate act of desperation, they summon the ghost of Edgar Allan Poe for help. Poe’s apparition floats above the Goths, Emos, and Vampires, takes a drag from a cigarette, and declares all of them “posers.”

Poe was a white man born in the 1820s. He was both Northern and Southern; born in Boston, raised in Virginia, he lived, worked, and died in the Northeast. But one’s affiliation with either the north or the south doesn’t automatically exonerate one or condemn the other. We know his family owned at least one slave because he sold one slave on their behalf.

In his only novel, The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket, black and Native American characters are described as ferocious, bloodthirsty savages. His stories “The Black Cat” and “Gold Bug” have been seen as metaphors for the fear of slave insurgencies, and he consistently codes the color white to imply purity and black as monstrous. Then there’s that cocky, big black bird. He doesn’t have H.P. Lovecraft’s blatant xenophobia but a more liquid unease wrought with guilt that seems more appropriate for American horror. Poe’s anxiety is an American anxiety, wary of this sleeping giant and its ramifications, the blackness we brought to our shores and the darkness we fostered.

America reveals what haunts it most in its romantic and gothic literature, Toni Morrison writes in Playing in the Dark:

Romance, an exploration of anxiety imported from the shadows of European culture, made possible the sometimes safe and other times risky embrace of quite specific, understandably human, fears: Americans’ fear of being outcast, of failings of powerlessness; their fear of boundarylessness, of Nature unbridled and crouched for attack; their fear of the absence of so-called civilization; their fear of loneliness, of aggression both external and internal. In short, the terror of human freedom—the thing they coveted most of all: [Romance] offered platforms for moralizing and fabulation, and for the imaginative entertainment of violence, sublime incredibility, and terror—and terror’s most significant, overweening ingredient: darkness, with all the connotative value it awakened.

“The Tell-Tale Heart,” “The Black Cat,” and “The Fall of the House of Usher” all have a similar theme: an attempt to get away with murder and the effort to deny it. Guilt haunts these protagonists, drives them mad, and that madness leads to their downfall. The black cat that was brought into the home and domesticated, becomes the focus of wrath:

I slipped a noose about its neck and hung it to the limb of a tree, —hung it with the tears of remorse at my heart; —hung it because I knew that it had loved me, and because I felt it had given me no reason of offense; —hung it because I knew that in doing I was committing a sin.

Walls were Poe’s go-to place for hiding corpses, he keeps the bodies close, he keeps them in the structure of the home, in the place where we think we are the most safe and secure, but the evidence is right on the other side of the plaster and the brink just inches away from the head of the bed. They live with their victims, stash them away, and try to go about their daily lives in an attempt to forget what they had done. The narrator in “The Black Cat” “soundly and tranquilly slept; aye slept even with the burden upon my soul.” In both “The Tell-Tale Heart” and “The Black Cat” the narrators are confident with the police, allow them in with the self-assured presumption of camaraderie with the authorities that only the privileged can afford. But they are tormented by their guilt, by “the beating of the hideous heart” and the “wailing shriek, half of horror and half of triumph.” In Poe’s America they don’t get away with it.

Adapted from Darkly: Black History and America’s Gothic Soul by Leila Taylor, published on November 12 by Repeater Books. Copyright © 2019 by Leila Taylor.