The men of today are born to criticize; of Achilles they see only the heel.

—Marie von Ebner-Eschenbach, 1880

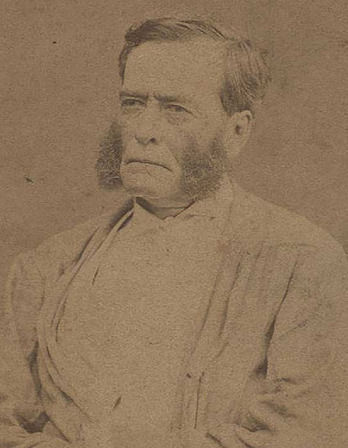

Members of the Hatfield clan posing with their weapons, West Virginia, c. 1897. © Pictures from History / Bridgeman Images.

Audio brought to you by Curio, a Lapham’s Quarterly partner

Feuds are pointless tragedies carried out for political, religious, or personal honor, thrust upon generation after generation, father to son (seldom mother to daughter, let us note). There are the Montagues and Capulets, and there are the Hatfields and McCoys: Shakespeare’s time in fair Verona, and post–Civil War in the verdant Appalachian Mountains. The meandering Tug Fork forms part of the West Virginia–Kentucky border in the Tug River Valley, an especially remote mountainous region. Real-life feuds, as opposed to those generated in the myriad minds of Shakespeare and company, are fueled by complex cultural and economic pressures. The story of the Hatfields and McCoys is one of endlessly conflicting details, but the tale is yet another condescending variation of Appalachia bashing: observe the ignorant hillbillies killing each other over the ownership of a hog. It’s (thankfully) no longer acceptable to be openly racist or sexist, to fat-shame or thin-exult, but it’s perfectly okay to bait Appalachia: no understanding of history necessary. But let us confine ourselves to the appropriated story of the Hatfields and McCoys (near as we can make out, as we say even in north-central West Virginia, an hour’s drive from Pittsburgh, where I grew up, a world away from Mingo or Logan Counties on the southern border of the state).

Like the Hasidim of today—among whom families of a dozen or more children are highly respected—Appalachian families in the mid-nineteenth century honored and needed large families. Hatfields, McCoys, and McCoy cousins the Clines were among the clans struggling to farm the rugged land. Devil Anse and Levisa Chafin “Vicey” Hatfield had thirteen children; Randall and first cousin Sally McCoy had sixteen or seventeen. Both the Hatfields and the McCoys were long established: Anderson “Devil Anse” Hatfield was descended from one William Hatfield, born about 1600 in England—first immigrant of his line, he was part of the Jamestown Colony, established in Virginia in 1607. Randall McCoy’s ancestors, several Scotch-Irish McCoy brothers who emigrated from Belfast in the early 1700s, traced their line to Kirkcudbright in Scotland. One of them was said to have accrued wealth as a mercenary for an English lord, but Randall McCoy brought no land to his marriage. Sally McCoy’s three hundred Kentucky acres became the McCoy homestead. Mountain families in the Tug Valley cleared their own land, built their own houses, raised their crops and livestock, delivered their own babies, and relied on herb-based medical care. They survived harsh mountain winters in an unspoiled Eden ruled by painter lion, bear, owl, and snake, and they lived unmolested by any but themselves for generations. Though Tug was originally a derivative of a Cherokee word, Native Americans saw what became West Virginia (the only state wholly within today’s Appalachia) as rugged lands reserved for spiritual ceremonies or hunting expeditions; they didn’t live in the steeply forested mountains in large groups. Land-hungry immigrants took what acreage they could. Most lived on isolated homesteads of a few hundred acres, with limited state or federal oversight, until the Civil War intervened.

America lost a generation in the War Between the States, a term that perhaps better describes the sovereign states of 1860s America. The Hatfield and McCoy men fought for the Confederacy, though neither owned slaves. Devil Anse may have earned his nickname in his early twenties when he was said to have single-handedly held off a company of Union soldiers from a stone pinnacle in the Battle of Devil’s Backbone. He was a first lieutenant and later a captain in the Virginia State Line, a unit that promised its soldiers they would complete their military service near their undefended homes. Charged with protecting the Kentucky-Virginia border against Union incursions, the VSL engaged in guerrilla warfare in mountains too forested and vast to admit opposing battalions. Tidewater and Piedmont Virginia regarded the western Virginia mountains as worthless frontier. West Virginia seceded from Virginia to defend the Union (a fact unknown to most Americans today), but loyalties to North and South were particularly mixed on the southern border. Union sympathizers attacked the Hatfield farm and forced the family to flee; Devil Anse requested leave to return home. Shortly after, along with dozens of other Confederate soldiers from what became the Forty-Fifth Battalion of the Virginia Infantry, he deserted the Confederacy but continued defending it in a Tug Valley partisan unit. Randall McCoy didn’t desert; he was captured on the Kentucky side of the river in July 1863, and suffered through the last two years of the war in Union prison camps.

Brother against brother was not unusual, though Asa Harmon McCoy, Randall McCoy’s brother, seems to have been a rare Unionist among the McCoys and Hatfields. He took part in an 1864 border raid on the farm of a friend of Devil Anse Hatfield, and Hatfield vowed revenge for the man’s murder. Harmon McCoy returned home from the war a year later and was likely killed by Devil Anse’s uncle Jim Vance, member of a Confederate home-guard unit called the Logan Wildcats. An eye-for-an-eye sense of justice seemingly prevailed, and no further violence erupted between the families for another thirteen years.

Despite battles won or lost, Appalachia and the entire South remained in economic decline for fifty years after Appomattox. Much of the Confederacy recovered, but the northeastern sons of wealthy capitalist families, who first saw the majestic forests of West Virginia during the war, wasted no time in acquiring timber rights to vast tracts of land. Rapid economic development, particularly in northeastern cities, exponentially increased demand for timber; pre–Big Coal, the forests were cut and shipped (mostly) north. Few West Virginians profited. Devil Anse was an exception. He established a successful timbering business, and five thousand acres of virgin timberland were the actual cause of the feud. Perry Cline, a McCoy relation living on the West Virginia side of the river, claimed that Devil Anse Hatfield was cutting trees on his land and threatened a lawsuit. Today the Cline family claims to have researched its title to the Grapevine lands near Grapevine Creek as far back as 1795, but Devil Anse prevailed in the dispute. In one version of the story, Anse filed a lawsuit of his own and was awarded the acreage. In yet another version, Perry Cline sold his half of the disputed West Virginia land to Anse in 1869. Two years later, yet to be paid the purchase price, Cline agreed to trade the original land and the “Old Home Place” Cline homestead property for Hatfield land along the Tug Fork near Pikeville, Kentucky. Anse expanded his timber operation and moved his family into the Cline homestead, known after as the Cline-Hatfield house. Cline moved to Kentucky, became a lawyer, bought more land, and began cultivating political connections he would later use against the Hatfields.

The so-called Hog Trial took place against a background of bitterness regarding Cline-McCoy loss of land in West Virginia. It’s hard not to recognize the hardships of the postwar decades in the mountains, particularly for the less affluent McCoys, for whom the butchering of a hog could mean the difference between eating or going hungry for some weeks. Fencing the steep land wasn’t practical, and livestock wandered between homesteads; farmers notched the ears of their animals as a form of branding. McCoy saw his notch on Floyd Hatfield’s hog and filed suit. Floyd, Anse’s cousin, lived on the Kentucky side of the river and was related to both families. Some say Randall McCoy’s actual motivation was anger that Floyd worked for Anse’s profitable timber operation. The local justice of the peace, “Preacher Anse” Hatfield, cousin to Devil Anse, impaneled a jury that was half Hatfield men, half McCoy men. McCoy juror Selkirk McCoy—son of Asa Harmon McCoy, the Union soldier murdered thirteen years before—worked, with two of his sons, among the thirty-five to forty men on the Hatfield timber crew. He apparently valued the present more than the past, and voted against Randall McCoy. No violence ensued, but the “betrayal” fueled resentment among the families. McCoy, a subsistence farmer and sometime ferryboat operator, was unable to provide economic stability or social or political status for his clan, while Hatfield’s success protected his family and employees from the economic decline endemic to the Tug Valley. The McCoy family was understandably frustrated, even furious, at the seemingly undefeated Hatfields.

Election days, on both sides of the river, were social gatherings that featured marksmanship contests, dancing, “best recipe” banquets, and the not so subtle trading and purchase of moonshine. The storied romance between Roseanna McCoy, Randall’s daughter, and Johnse Hatfield, Devil Anse’s eldest son, supposedly began at an Election Day celebration near Blackberry Creek in 1880. Roseanna was naive enough to believe the worldlier Johnse’s declarations of love; perhaps he believed them himself. They drifted away from the crowds like a couple in a Van Morrison song and literally lost track of time, returning after the polling place was closed. Nearly everyone had departed, including Roseanna’s brothers, whom Randall had charged with bringing Roseanna home. Instead, Johnse Hatfield took her to West Virginia, where she slept upstairs with his sisters. Randall McCoy had sent his sons back to the polling place in the dark, where they called for Roseanna in the woods and along the river.

The next morning Johnse and Roseanna declared they wanted to marry. Randall McCoy disowned his daughter, and the Hatfields also forbade the marriage. Devil Anse refused to defy Randall McCoy and warned Johnse that Roseanna’s brothers would kill him. “Vicey” Hatfield, mother to the thirteen Hatfield children, refused to relent as well, certain the marriage would not last and well aware that Roseanna and any children she might bear would risk starvation with no male provider. Her own family had turned her out, and hostilities would prevent the Hatfields from helping her. They allowed Roseanna to stay, though, at Johnse’s urging. The couple enjoyed an idyllic few weeks. Eventually, several McCoy brothers found them together, imprisoned Johnse in a Kentucky hunting cabin, and had him arrested on an outstanding bootlegging warrant. Roseanna, in a romantic gesture worthy of a Shakespearean heroine, defied her own family to ride through the night woods and summon Devil Anse. The Hatfields surrounded the McCoy brothers and rescued Johnse before he could be taken to jail in Pikeville the next morning. Johnse and Roseanna continued to live with the Hatfields, and Roseanna announced her pregnancy, but the Hatfields again forbade the marriage, certain their permission would provoke the McCoys. Roseanna left to live with an aunt in Stringtown, Kentucky, some two hours (on today’s paved roads) deeper into Kentucky from Pikeville, and gave birth to a daughter, Sarah Elizabeth. The baby lived less than a year. Johnse supposedly tried to send messages to Roseanna through her cousin Nancy McCoy. Nancy may have consoled Johnse in the wake of his ill-fated love affair or used him to plot revenge on the Hatfields. In any case, sometime the same year, Johnse Hatfield and Nancy McCoy married, no permission asked. The marriage was brief, but let us continue.

On Election Day 1882, on the Kentucky side of the river, a fight broke out between several McCoy brothers and Ellison Hatfield, Devil Anse’s brother. The McCoys shot the unarmed Ellison Hatfield in the back and stabbed him twenty-six times, all in sight of the festive crowd. Tolbert, Pharmer, and Bud McCoy were arrested by constables, but Devil Anse organized an interception and took the three back to West Virginia, where Ellison Hatfield died over three agonizing days: one day, it was said, for each of his murderers. The Hatfield men then tied the McCoy brothers to pawpaw trees just over the Kentucky line and riddled their bodies with bullets. Vigilante justice common to the area seemed to define their revenge as justified. Though Kentucky indicted up to twenty Hatfields—including Devil Anse—at Randall McCoy’s insistence, law enforcement made no attempt at extradition, which would have required deputizing an army and invading a sovereign state. Five years passed before Perry Cline convinced Kentucky governor Simon Bolivar Buckner to reissue the indictments. Even given lawyer Cline’s carefully encouraged political connections, the time lapse is puzzling until one considers a central fact: certain Kentucky business interests had proclaimed the wild and inaccessible Tug Valley so rich in coal that the Norfolk and Western Railway planned to build a railroad through it. Cline had continued title litigation, hoping to recover his (now suddenly much more valuable) land, while politics decreed the Hatfields disadvantageous to the region’s economic development. Kentucky announced a bounty on Hatfields in 1887. Scores of bounty hunters descended. One, a gunslinger named Frank Phillips (no relation, I hope), referred to himself as Bad Frank and was actually deputized; he hunted the Hatfields mercilessly and killed or jailed several. Devil Anse moved his clan higher into the mountains and planned an assault on Randall McCoy’s cabin, unaware that McCoy was no longer in control and that Perry Cline was orchestrating the bounty.

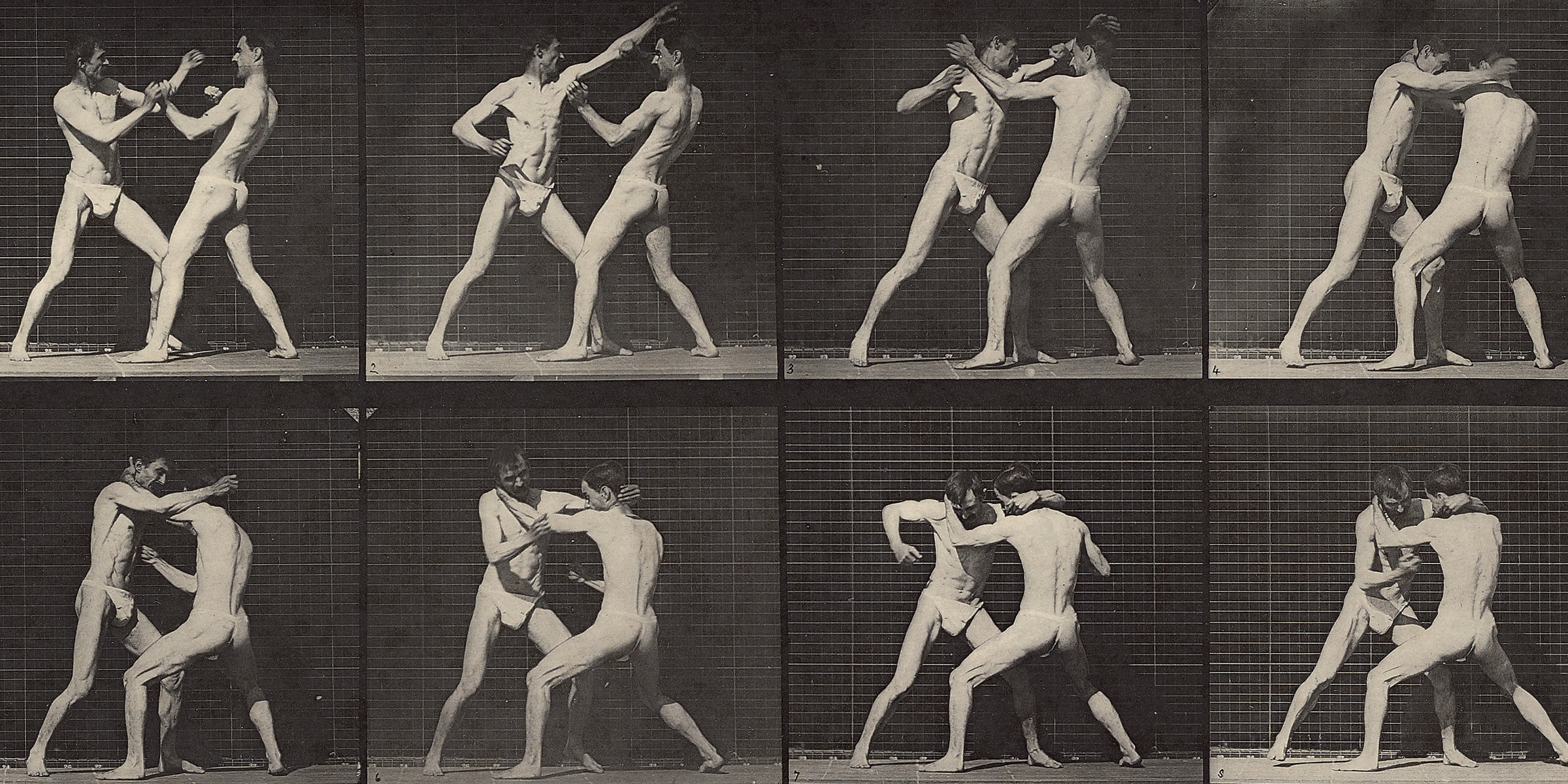

Men wrestling, from the series Animal Locomotion, by Eadweard Muybridge, 1887. The J. Paul Getty Museum, Los Angeles. Digital image courtesy the Getty’s Open Content Program.

Eight Hatfields surrounded Randall McCoy’s cabin on the first night of 1888, led by Jim Vance, who was so impulsively violent that he was known as Crazy Jim. Devil Anse was not among the group, which included his two sons Johnse and Cap, his eldest brother, Valentine “Wall” Hatfield, two of Wall’s brothers-in-law, Doc and Pliant Mahon, and the murdered Ellison Hatfield’s illegitimate son, Ellison “Cottontop” Mounts. Cottontop was a mentally challenged albino, hence his nickname, which referred not only to his white blond hair but also to the cottony vacuousness of his perceptions. The Hatfields surrounded the McCoy cabin, sending Cottontop and Johnse to cover the back, and called out Randall McCoy at dawn. They threatened to fire the house if he didn’t surrender. Most of the adult McCoy children were elsewhere. Three daughters were home: spinster Alifair, age twenty-nine, who had suffered polio as a child and was somewhat disabled, and teenagers Adelaide and Fanny. One grown son, Calvin, shouted that Randall wasn’t home, aiming his rifle through the chinks of the cabin as he spoke. The house went up in flames as Randall escaped out the back. Some accounts say he was carrying an infant grandchild, others that his wife, Sally, urged him to leave, hoping the McCoys would spare the rest of the family. The Hatfields shot Calvin as he ran, armed, out the front. Cottontop, unfortunately a good shot, killed Alifair as she tried to get to the well for water: one impaired child shot another. The younger girls disappeared into the woods. Various accounts maintain that the frantic Sally McCoy charged Jim Vance; he clubbed her to the ground with his rifle butt. She never fully recovered. The Hatfields fled back across the river.

Championing the death of innocent Alifair McCoy, Perry Cline had little difficulty convincing Kentucky to authorize a posse. Bad Frank Phillips led dozens of men across the mountainous border to kill Jim Vance in the woods after he refused arrest. Phillips arrested and jailed others. Issues of due process and illegal extradition resulted in threats; the governors of West Virginia and Kentucky considered ordering their respective militias to invade each other’s states. Instead, litigation proceeded all the way to the Supreme Court. Frank Phillips was determined to wipe out the Hatfields completely before any ruling could intervene. He stormed across Grapevine Creek and found a force of Hatfields arrayed against his posse on the very land whose disputed possession had ignited the feud sixteen years before. The January 19 battle of Grapevine Creek was the only organized battle of armed opposing forces in the feud; Phillips’ posse killed two Hatfields and executed a West Virginia deputy who had surrendered. Devil Anse and many of his kin retreated, but Bad Frank arrested eight Hatfields, who would stand trial in Kentucky. In 1888 the Supreme Court ruled 7–2 in Kentucky’s favor (Mahon v. Justice, 127 U.S. 700) that even if a fugitive is returned from the asylum state illegally, no federal law prevents a trial. Seven Hatfields were sentenced to life in prison. Cottontop Mounts was so mentally challenged at his trial that he struggled to repeat the confession that prosecuting attorney Perry Cline had tried to teach him. Stories circulated that Johnse Hatfield had actually shot Alifair; other stories held that Johnse, still heartsick over Roseanna, had aimed into the air and refused to shoot any of the McCoys. By this time Nancy McCoy had divorced him and married Bad Frank Phillips, whom she may have assisted by spying on the Hatfields. Roseanna “had died of a broken heart,” a euphemism for suicide. Cottontop was hanged in Pikeville before an audience of thousands, and the press duly recorded his last words: “The Hatfields made me do it.”

Devil Anse refused to engage in more feuding. Wall Hatfield died in prison within two years. Doc and Pliant Mahon were paroled after fourteen years. Johnse Hatfield lit out for British Columbia, where he timbered for several years, constantly fleeing bounty hunters and detectives until he decided he was safer evading arrest in West Virginia. He succeeded until 1898, when he was sentenced to life for his part in the New Year’s Day massacre. Six years into his sentence, Johnse saved the life of a prison warden, killing another inmate in a knife fight. He was paroled and resumed his timbering business in West Virginia. Randall McCoy perished at eighty-eight when he fell into a cooking fire. Devil Anse Hatfield outlived Randall and died of natural causes at eighty-one. His descendants honored him with a life-size statue of Italian marble at the Hatfield Cemetery near Newtown, West Virginia; the sculpture lists his thirteen children on its granite base.

From here the Hatfield-McCoy feud breaks down into commodified vagaries, reaching a low point on the TV show Family Feud in 1979. Certain descendants played each other for a cash prize in the presence of an embarrassed pig. The Hatfields won $11,272, the McCoys, $8,459, but the show made a point of raising the McCoy’s winnings to $11,273, thereby crowning a victor and insulting all involved.

How can we bear misfortune most easily? If we see our enemies faring worse.

—Thales of Miletus, 585 BCToday there’s a Hatfield-McCoy historic site, funded by a federal grant and informed by the work of local historians. A compact disc is available; a six-hundred-mile trail system—the Hatfield-McCoy Trails—caters to ATV enthusiasts. A Hatfield-McCoy Festival attracts hundreds and includes marathons, motorcycle rides, a cornbread contest, pancake breakfasts, arts-and-crafts fairs. Sixty Hatfield-McCoy descendants declared an official truce, a proclamation of peace between the families, on June 14, 2003, to show that “if the two families could reach an accord, others could also.” Reo Hatfield, of Waynesboro, Virginia, tailored his message to a post-9/11 world: “When national security is at risk, Americans put their differences aside…We’re not saying you don’t have to fight, because sometimes you do have to fight. But you don’t have to fight forever.” The Hatfields and McCoys might “symbolize violence and feuding and fighting,” added Ron McCoy. “Hopefully people will realize that’s not the final chapter.”

Sadly, the final chapter seems overwhelmed by the human tendency to simplify another dark story of American economic exploitation and deprivation. The Hatfield-McCoy feud is still used nationally as a shameful Appalachian joke that blames centuries of exploitation on those who were exploited. Yes, the local economy of the Tug River Valley, blessed and isolated by its mountains, profits by festivals, but history should be more than a tourist destination.