My dear friend,

This is not the republic I came to see. This is not the republic of my imagination. I infinitely prefer a liberal monarchy—even with its sickening accompaniments of court circulars and kings of Prussia—to such a government as this. In every respect but that of national education, the country disappoints me. The more I think of its youth and strength, the poorer and more trifling in a thousand respects it appears in my eyes. In everything of which it has made a boast—excepting its education of the people and its care for poor children—it sinks immeasurably below the level I had placed it upon. And England, even England, bad and faulty as the old land is, and miserable as millions of her people are, rises in the comparison. Strike down the established church, and I would take her to my heart for better or worse and reject this new love without a pang or moment’s hesitation.

You live here, Macready, as I have sometimes heard you imagining! You! Loving you with all my heart and soul and knowing what your disposition really is, I would not condemn you to a year’s residence on this side of the Atlantic for any money. Freedom of opinion! Where is it? I see a press more mean and paltry and silly and disgraceful than any country ever knew—if that be its standard, here it is. I speak of Bancroft and am advised to be silent on that subject, for he is “a black sheep—a democrat.” I speak of Bryant and am entreated to be more careful—for the same reason. I speak of international copyright and am implored not to ruin myself outright. I speak of Miss Martineau, and all parties—slave upholders and abolitionists; Whigs, Tyler Whigs, and Democrats—shower down upon her a perfect cataract of abuse. “But what has she done? Surely she praised America enough”—“Yes, but she told us of some of our faults, and Americans can’t bear to be told of their faults. Don’t split on that rock, Mr. Dickens, don’t write about America—we are so very suspicious.” Freedom of opinion! Macready, if I had been born here, and had written my books in this country—producing them with no stamp of approval from any other land—it is my solemn belief that I should have lived and died poor, unnoticed, and “a black sheep”—to boot. I never was more convinced of anything than I am of that.

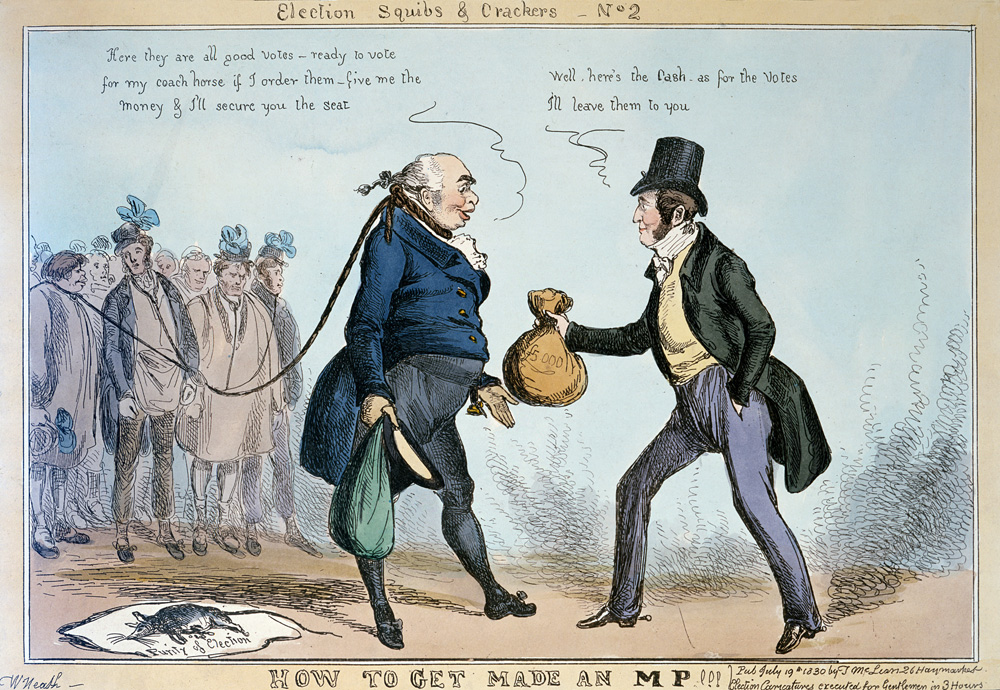

Election Squib & Crackers No. 2: How to Get Made an MP, by William Heath, 1830. © The Bridgeman Art Library.

The people are affectionate, generous, openhearted, hospitable, enthusiastic, good humored, polite to women, frank and cordial to all strangers; anxious to oblige, far less prejudiced than they have been described to be, frequently polished and refined, very seldom rude or disagreeable. I have made a great many friends here—even in public conveyances—whom I have been truly sorry to part from. In the towns, I have formed perfect attachments. I have seen none of that greediness and indecorum on which travelers have laid so much emphasis. I have returned frankness with frankness—met questions not intended to be rude with answers meant to be satisfactory—and have not spoken to one man, woman, or child of any degree, who has not grown positively affectionate before we parted. In the respects of not being left alone, and of being horribly disgusted by tobacco chewing and tobacco spittle, I have suffered considerably. The sight of slavery in Virginia, the hatred of British feeling upon that subject, and the miserable hints of the impotent indignation of the South have pained me very much—on the last head, of course, I have felt nothing but a mingled pity and amusement—on the others, sheer distress. But however much I like the ingredients of this great dish, I cannot but come back to the point from which I started and say that the dish itself goes against the grain with me and that I don’t like it.

You know that I am, truly, a liberal. I believe I have as little pride as most men, and I am conscious of not the smallest annoyance from being hail fellow well met with everybody. I have not had greater pleasure in the company of any set of men among the thousands whom I have received (I hold a regular levee every day, you know, which is duly heralded and proclaimed in the newspapers) than in that of the Carmen of Hertford, who presented themselves in a body in their blue frocks, among a crowd of well-dressed ladies and gentlemen, and bade me welcome through their spokesmen. They had all read my books and all perfectly understood them. It is not these things I have in my mind when I say that the man who comes to this country a radical and goes home again with his old opinions unchanged must be a radical on reason, sympathy, and reflection, and one who has so well considered the subject that he has no chance of wavering.

From a letter to William Macready. After publishing The Pickwick Papers and Oliver Twist, Dickens embarked on a reading tour of the U.S., telling the crowd at one banquet that he had “dreamed by day and night for years of setting foot upon this shore.” He met Henry Wadsworth Longfellow in Boston, Edgar Allan Poe in Baltimore, and President John Tyler in Washington, DC. His addressee in this letter was a well-known actor; while Macready was playing Macbeth in 1849 in New York City, supporters of his American acting rival, Edwin Forrest, stormed the theater in which Macready was performing and at least twenty people died.

Back to Issue