If you have any soul worth expressing, it will show itself in your singing.

—John Ruskin, 1865

Page from Dave Brubeck’s score for “The Duke,” reproduction after Edward Colker, 1963. © Philadelphia Museum of Art, gift of the artist, 1964.

Audio brought to you by Curio, a Lapham’s Quarterly partner

The first time I heard The Queen’s Suite, I was at work, listening to a collection of piano music to drown out the sounds of the office. I hadn’t been paying particular attention to the music until a solo piano—Duke Ellington—began to play a phrase, a single figure of just a few lilting notes, repeated slowly at first, then more quickly, finally building into a kind of berceuse.

The song, “The Single Petal of a Rose,” was among the most beautiful and personal melodies Ellington ever wrote. It was the centerpiece of The Queen’s Suite, six songs he and his collaborator Billy Strayhorn composed for Queen Elizabeth II in 1958. Five of the six songs represent different musical landscapes—a grove full of fireflies, or a mockingbird singing at sunset—seen by Ellington in his travels around the world. Several of these, he wrote in his autobiography, represented some of the most moving moments of his life. It is a remarkable artistic achievement, even by the standards of such a prolific composer. But after recording it, he gave to the queen what he claimed was the only copy, refusing to release the album in his lifetime.

Music—A Sequence of Ten Cloud Photographs, No. 1, by Alfred Stieglitz, 1922. © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, gift of David A. Schulte, 1928.

It’s hard to think of anything else quite like this act of musical secrecy. The Wu-Tang Clan seems to have tried something similar with its recent album, Once Upon a Time in Shaolin, released only in a single-copy pressing—though rather than being given freely to a benign monarch, it was sold for $2 million to a more or less universally reviled pharmaceutical executive, Martin Shkreli. Not quite the same. Of unreleased and unperformed works and works in progress there are, of course, many. Countless composers have cast aside unfinished drafts or burned finished pieces they didn’t think were up to snuff. Tchaikovsky, for instance, destroyed his opera Undine in 1873, reusing bits of it in subsequent works (perhaps most famously the pas de deux from Swan Lake). Others have tried withholding pieces from general performance in order to keep creative control (Wagner wanted Parsifal performed only at Bayreuth) or for personal safety (Shostakovich prudently withheld his song cycle From Jewish Folk Poetry until after Stalin’s death). At least one, Kaikhosru Sorabji, banned the performance of his own work because of its technical difficulty (“No performance at all is preferable to an obscene travesty”). Then there are the many works that simply weren’t recorded: untold numbers of blues artists playing roadside dives, or jazz musicians like Buddy Bolden unfurling genius improvisations that were lost the moment they left the horn. But what Ellington did with The Queen’s Suite—wishing to limit so drastically the exposure of such a complete and unimpeachably lovely work—seems almost inexplicable.

In 1958 Ellington made his way to the Leeds Festival for a command performance for the royal family. It was two years into the midcareer renaissance he and his band experienced after the 1956 Newport Jazz Festival, when saxophonist Paul Gonsalves’ seemingly endless choruses on “Diminuendo and Crescendo in Blue” had Newport’s subdued WASPs dancing so hard that the authorities feared a riot. Not long after, Ellington was on the cover of Time. It was also one year after Governor Orval Faubus and the Little Rock Nine, and Louis Armstrong’s interview in which he called Faubus a no-good motherfucker. Big bands had mostly died off by then, victims of inflation, television, the decline of dance halls, and the rise of rock. But Ellington’s persisted.

When he met the queen he seems to have been taken with her. Harvey G. Cohen, in his excellent book Duke Ellington’s America, describes the meeting:

Various reports confirm that they charmed each other. She asked when he first visited her country, and Ellington diplomatically replied, “1933, your Majesty, years before you were born.” She expressed regret concerning her inability to attend his concerts on the tour, at which point, according to Melody Maker, Ellington’s “face puckered into a huge smile.” “In that case, your Majesty, I’d like to write a very special composition for you—a real royal suite.”

A photo of the scene seems to have captured that very smile. Ellington beams, incandescent, perhaps an indication of a special moment in the life of a musician who had played for his share of grandees. In an interview some years later, he said, “I told her that she was so inspiring and that something musical would surely come of it. She said she would be listening, so I wrote an album for her.”

Shortly thereafter, he set himself (and Strayhorn, who composed “Northern Lights,” one of the songs from the suite) to writing. In early 1959 he took his compositions to the band, which turned in an impressive performance—better than average for the period. According to Gary Marmorstein, author of The Label: The Story of Columbia Records, “a master was prepared, a gold disc issued privately to the royal family—according to an agreement between Ellington and his producer, Irving Townsend—with Ellington retaining rights to release the entire Suite at a later date. Eventually Ellington reimbursed Columbia $2,500 in production costs to buy it back.” Jazz historian Gary Giddins has written that probably no one outside Ellington’s inner circle knew of The Queen’s Suite until two years after his death in 1974. It was released posthumously by Norman Granz. In 1976 it won a Grammy, along with two other suites.

Even for Ellington, this was unusual behavior. He was famous for constantly writing and recording music—it’s estimated he wrote anywhere between two thousand and five thousand pieces—and he kept a stockpile of unreleased recordings (many from the last decade of his life) so large that it dwarfed the output of many major artists. Much of the unreleased material was variously made up of experiments in new styles and general overflow, music that record labels wouldn’t take a chance on, whether because he had simply published too much or the work was deemed too artistically ambitious. Yet The Queen’s Suite seems to have been different. Though the album was never released in his lifetime, he did perform selections from it in concerts, and one of its songs, “The Single Petal of a Rose,” was widely requested. The connection to the queen likely would have made the album quite marketable. Ellington himself even seems to have had a particular personal investment in the work. According to Townsend, the composer worked harder on the piece than anything else he’d ever seen.

There is something almost devotional about the way Ellington dedicated this album. In many respects, the closest historical analogue was the Albumblätt, or “album leaf,” a kind of composition originally written in the album of a friend or patron and often dedicated to that person. Initially these works—the form was never really defined—were slight, but over time Albumblätter became more ambitious and substantial. Beethoven’s “Für Elise” may be the best-known example, composed in 1810 but not published until 1867, after it was discovered among the papers of a former student.

A Masked Ball in Bohemia (detail), attributed to Andreas Altomonte, c. 1748. © The Metropolitan Museum of Art, bequest of Mariana Griswold Van Rensselaer, 1934.

As an intimate offering, it is reminiscent of prayer. In fact, it shares similarities with certain works of sacred music. For centuries the Catholic Church was said to have kept a piece of music to be performed only during Holy Week, and only in the Sistine Chapel. The song, “Miserere,” was a choral work sung during the Tenebrae, a service in which fifteen candles were gradually extinguished, one after each psalm, until only one was left and the service proceeded in tenebris—in darkness.

Stendhal, who witnessed the service and heard the “Miserere,” described it in his biography of Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart:

When the “Miserere” starts, the pope and the cardinals prostrate themselves: the tapers cast their light on the Last Judgment that Michelangelo painted on the wall behind the altar. As the “Miserere” proceeds, the tapers are extinguished one by one; the faces of all the wretched figures that Michelangelo painted with such terrible energy become even more dramatic in the pale glow of the last remaining tapers. When the “Miserere” is about to finish, the kapellmeister, who is conducting, slows the tempo imperceptibly, and the singers lower the volume of their voices so the music slowly fades away; the sinner, overwhelmed by the majesty of his God and prostrate before his throne, seems to be waiting silently for the voice of his judge to be heard.

“The sublime effect of this music,” Stendhal continued, “seems to me to be dependent on the manner in which it is sung and on the place where it is executed.” So much so that the church refused general publication of the composition or its performance elsewhere. (Several copies of the piece made their way to various potentates, but one of them, the Holy Roman emperor, was said to be so livid on hearing his version that his complaints to the pope caused the choirmaster to be fired. It was only after the choirmaster sent a letter to the emperor explaining why it had to be performed in the special manner of the Sistine choir—which made use of embellishments not included in the written score—that he was reinstated.)

Things persisted this way for decades until a young Mozart, then about fourteen years old, heard the performance, went home, and wrote it out. According to some sources, he went a second time, smuggling his transcription into the Sistine Chapel in his hat in order to double-check his work.

Mozart’s father, Leopold, described the episode in a letter to his wife, written in the spring of 1770:

You have often heard of the famous “Miserere” in Rome, which is so greatly prized that the performers in the chapel are forbidden on pain of excommunication to take away a single part of it, to copy it, or to give it to anyone. But we have it already. Wolfgang has written it down, and we would have sent it to Salzburg in this letter if it were not necessary for us to be there to perform it. But the manner of performance contributes more to its effect than the composition itself. So we shall bring it home with us. Moreover, as it is one of the secrets of Rome, we do not wish to let it fall into other hands, ut non incurramus mediate vel immediate in censuram Ecclesiae [so that we shall not incur the censure of the church now or later].

Music is a beautiful opiate, if you don’t take it too seriously.

—Henry Miller, 1945In part, as Stendhal and Leopold wrote, there seem to have been two practical reasons for confining the music to the chapel: only its choir knew the embellishments that gave the otherwise simple song its special qualities, and it drew some of its power from its interplay with Michelangelo’s frescoes. But the refusal to allow it out into the world conferred dignity on the piece and on the proceedings of which it was such an integral part.

In his autobiography, Music Is My Mistress, Ellington recalled one of the scenes that inspired part of the album:

One evening we were a little late leaving Tampa, en route to West Palm Beach to make a gig. The weather was wonderful, and it was just about sunset when, halfway across Florida, we passed a bird. We didn’t see it, but we heard its beautiful call. I asked Harry Carney if he heard it and he said, “Yeah.” We were a little too pushed for time, and going too fast to stop or go back and thank the bird, so I pulled out my pencil and paper and wrote that lovely phrase down. I spent the next two or three days whistling it to the natives and inquiring what kind of bird it could have been that sang such a beautiful melody. Finally, I was convinced it had to be a mockingbird. I made an orchestration around that melody, titled it “Sunset and the Mockingbird,” and included it in The Queen’s Suite as one of the “beauty” experiences of my life.

Another one of the songs was drawn from a separate road trip:

We came out of Cincinnati late one night, took a road to the east on the south shore of the Ohio River, and got lost while searching for the country club we were supposed to play. We ran into an area where the sultry moon was half-hidden by the trees it silhouetted. We stopped short, for there, in this huge arena, with the trees as a backdrop, were, it seemed, millions of lightning bugs, dancing in the air. It was a perfect ballet setting, and down below in a gully, like an orchestra pit, could be heard the croaking of frogs. The number this inspired was called “Lightning Bugs and Frogs.”

These passages seem to indicate a deep investment in the music, a distillation of some of the most quietly awe-inspiring moments in the life of a man who had seen a great deal that inspired awe. But Ellington’s own accounts of his life can be unreliable. One of his biographers, Terry Teachout, wrote, “He talked not to explain himself but to conceal himself. Even Ruth, his adoring younger sister, said that he ‘definitely wasn’t direct. He wasn’t direct with anybody about anything.’ ” Pointing to a similar example, Teachout mentions Ellington’s description of his song “Harlem Air Shaft.” “You hear fights,” Ellington said, “you smell dinner, you hear people making love. You hear intimate gossip floating down. You hear the radio. An air shaft is one great big loudspeaker.” Unfortunately, the song was first called “Once Over Lightly,” a title, as Teachout notes, “that has nothing to do with life in a Harlem apartment house.”

Ellington’s unpublished writing may give a more accurate idea of his mind. In Duke Ellington’s America, Cohen quotes long passages from Ellington’s unpublished outline for Black, Brown, and Beige, perhaps the work that meant the most to him and one that he never quite finished. The text indicates a rare moment of insecurity, doubt about himself and his work:

And so your song has stirred the souls

Of men in strange and distant places…

But did it ever speak to them

Of what you really are?…

How could they ever fail to hear

The hurt and pain and anguish

Of those who travel dark, lone ways

The soul in them to languish?

And was the picture true

Of you? The camera eye in focus…

Or was it all a sorry bit

Of ofay hocus-pocus?

In spite of his celebrity and success, Ellington still faced racism his entire career, from the early days of the Cotton Club, done up like a plantation, to the less overt racism of critics sniffing that his later, larger, more ambitious works were beyond his ken and that he should confine himself to miniatures, the three-minute forms of his early career. The dedication of The Queen’s Suite may certainly have been a gesture of respect and admiration for the queen, but for someone like Ellington, who composed so much of such genius but wasn’t always treated accordingly, the act of a single dedication may have been intended to confer legitimacy and dignity not just on the queen but on the music itself.

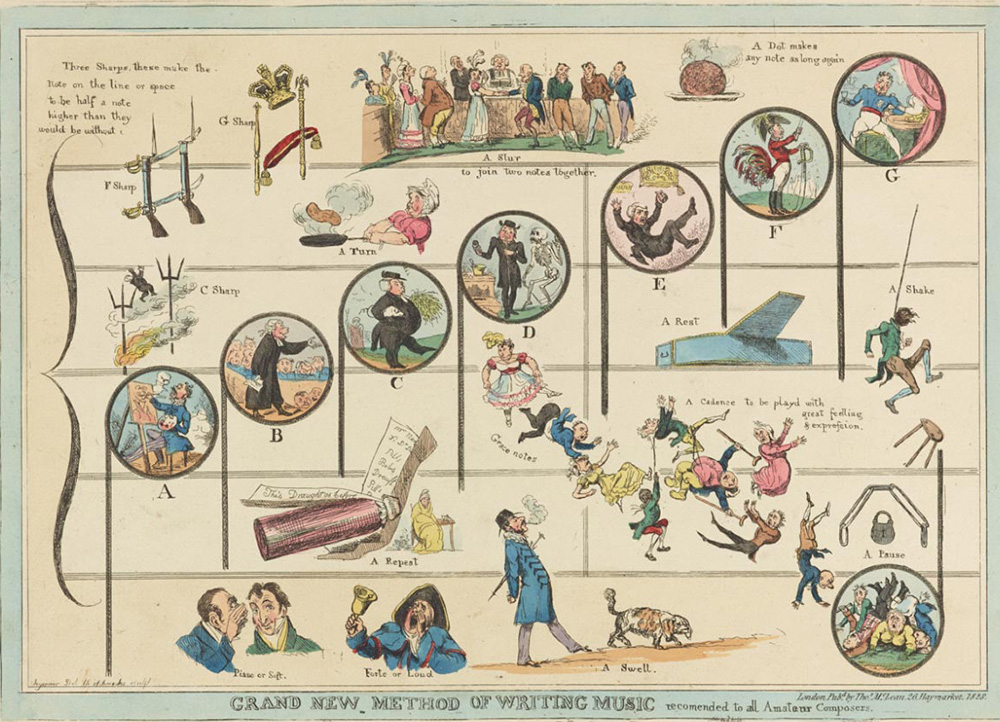

Grand New Method of Writing Music Recommended to All Amateur Composers, by Robert Seymour, 1828. © Philadelphia Museum of Art, William H. Helfand Collection, 2012.

“What we could not say openly, we expressed in music,” Ellington once wrote, emphasizing that black American music was “forged from the very white heat of our sorrows.” Whether his account of The Queen’s Suite’s origins is to be believed, the music itself is still there and among the loveliest of his works. His own description of it seems the most apt: “‘The Single Petal of a Rose,’ so delicate, fragile, gentle, luminous. Only God could make one, and like love, it should be admired but not analyzed.”