What was I to do? Where to go? Oh, intolerable questions, when I could do nothing and go nowhere! When a long way must yet be measured by my weary, trembling limbs before I could reach human habitation—when cold charity must be entreated before I could get a lodging: reluctant sympathy importuned, almost certain repulse incurred, before my tale could be listened to or one of my wants relieved!

I touched the heath: it was dry, and yet warm with the heat of the summer day. I looked at the sky; it was pure: a kindly star twinkled just above the chasm ridge. The dew fell, but with propitious softness; no breeze whispered. Nature seemed to me benign and good; I thought she loved me, outcast as I was; and I, who from man could anticipate only mistrust, rejection, insult, clung to her with filial fondness. Tonight, at least, I would be her guest, as I was her child: my mother would lodge me without money and without price. I had one morsel of bread yet: the remnant of a roll I had bought in a town we passed through at noon with a stray penny—my last coin. I saw ripe bilberries gleaming here and there, like jet beads in the heath. I gathered a handful and ate them with the bread. My hunger, sharp before, was, if not satisfied, appeased by this hermit’s meal. I said my evening prayers at its conclusion and then chose my couch.

Beside the crag the heath was very deep: when I lay down, my feet were buried in it; rising high on each side, it left only a narrow space for the night air to invade. I folded my shawl double and spread it over me for a coverlet; a low, mossy swell was my pillow. Thus lodged, I was not, at least at the commencement of the night, cold.

My rest might have been blissful enough, only a sad heart broke it. It plained of its gaping wounds, its inward bleeding, its riven chords. It trembled for Mr. Rochester and his doom; it bemoaned him with bitter pity; it demanded him with ceaseless longing; and, impotent as a bird with both wings broken, it still quivered its shattered pinions in vain attempts to seek him.

Worn out with this torture of thought, I rose to my knees. Night was come, and her planets were risen: a safe, still night: too serene for the companionship of fear. We know that God is everywhere; but certainly we feel his presence most when his works are on the grandest scale spread before us; and it is in the unclouded night sky, where his worlds wheel their silent course, that we read clearest his infinitude, his omnipotence, his omnipresence. I had risen to my knees to pray for Mr. Rochester. Looking up, I, with tear-dimmed eyes, saw the mighty Milky Way. Remembering what it was—what countless systems there swept space like a soft trace of light—I felt the might and strength of God. Sure was I of his efficiency to save what he had made: convinced I grew that neither earth should perish, nor one of the souls it treasured. I turned my prayer to thanksgiving: the Source of Life was also the Savior of spirits. Mr. Rochester was safe; he was God’s, and by God would he be guarded. I again nestled to the breast of the hill, and ere long in sleep forgot sorrow.

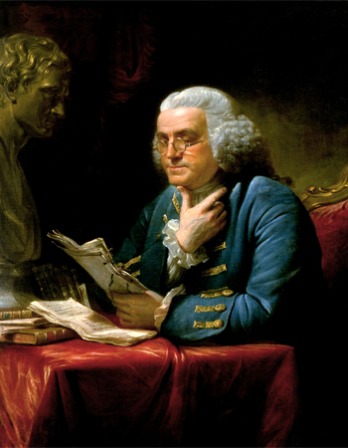

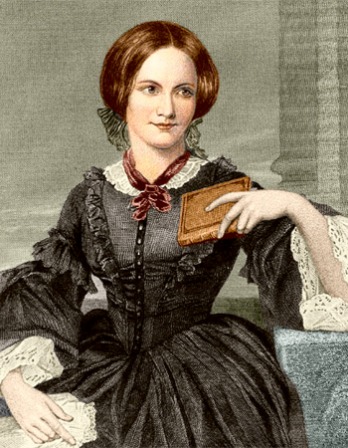

From Jane Eyre. Having fled Thornfield Hall and her love, Edward Rochester, Jane finds herself experiencing a dark night of the soul. Although Rochester had stood between Jane “and every thought of religion, as an eclipse,” scholar Muireann O’Cinneide writes that, away from him, Jane can now finally see the sky and reflect on a spiritual order on his behalf. It “is a curious mixture,” says O’Cinneide, “of intense self-subordination and intense self-aggrandizement.” Published under the pseudonym Currer Bell, Jane Eyre was a runaway success.

Back to Issue