The home plantation of Colonel Lloyd wore the appearance of a country village. All the mechanical operations for all the farms were performed here. The shoe making and mending, the blacksmithing, cartwrighting, coopering, weaving, and grain grinding were all performed by the slaves on the home plantation.

The whole place wore a businesslike aspect, very unlike the neighboring farms. The number of houses, too, conspired to give it advantage over the neighboring farms. It was called by the slaves the Great House Farm. Few privileges were esteemed higher by the slaves of the out-farms than that of being selected to do errands at the Great House Farm. It was associated in their minds with greatness. A representative could not be prouder of his election to a seat in the American Congress than a slave on one of the out-farms would be of his election to do errands at the Great House Farm. They regarded it as evidence of great confidence reposed in them by their overseers; and it was on this account, as well as a constant desire to be out of the field from under the driver’s lash, that they esteemed it a high privilege, one worth careful living for. He was called the smartest and most trusty fellow who had this honor conferred upon him the most frequently. The competitors for this office sought as diligently to please their overseers as the office seekers in the political parties seek to please and deceive the people. The same traits of character might be seen in Colonel Lloyd’s slaves as are seen in the slaves of the political parties.

The slaves selected to go to the Great House Farm, for the monthly allowance for themselves and their fellow slaves, were peculiarly enthusiastic. While on their way, they would make the dense old woods, for miles around, reverberate with their wild songs, revealing at once the highest joy and the deepest sadness. They would compose and sing as they went along, consulting neither time nor tune. The thought that came up came out—if not in the word, in the sound—and as frequently in the one as in the other. They would sometimes sing the most pathetic sentiment in the most rapturous tone, and the most rapturous sentiment in the most pathetic tone. Into all of their songs they would manage to weave something of the Great House Farm. Especially would they do this when leaving home. They would then sing most exultingly the following words:

I am going away to the Great House Farm!

O yea! O yea! O!

This they would sing, as a chorus, to words which to many would seem unmeaning jargon, but which, nevertheless, were full of meaning to themselves. I have sometimes thought that the mere hearing of those songs would do more to impress some minds with the horrible character of slavery than the reading of whole volumes of philosophy on the subject could do.

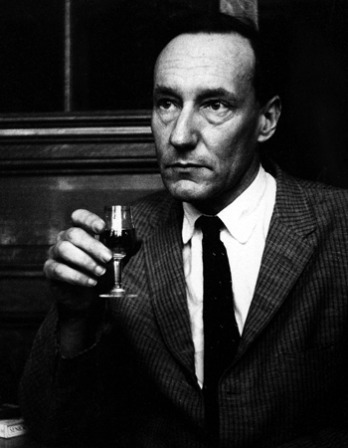

Ella, by Max Ferguson, 1989. © Private Collection / Bridgeman Images.

I did not, when a slave, understand the deep meaning of those rude and apparently incoherent songs. I was myself within the circle, so that I neither saw nor heard as those without might see and hear. They told a tale of woe which was then altogether beyond my feeble comprehension; they were tones loud, long, and deep; they breathed the prayer and complaint of souls boiling over with the bitterest anguish. Every tone was a testimony against slavery, and a prayer to God for deliverance from chains. The hearing of those wild notes always depressed my spirit and filled me with ineffable sadness. I have frequently found myself in tears while hearing them. The mere recurrence to those songs, even now, afflicts me; and while I am writing these lines, an expression of feeling has already found its way down my cheek. To those songs I trace my first glimmering conception of the dehumanizing character of slavery. I can never get rid of that conception. Those songs still follow me, to deepen my hatred of slavery, and quicken my sympathies for my brethren in bonds. If anyone wishes to be impressed with the soul-killing effects of slavery, let him go to Colonel Lloyd’s plantation and, on allowance day, place himself in the deep pinewoods, and there let him, in silence, analyze the sounds that shall pass through the chambers of his soul—and if he is not thus impressed, it will only be because “there is no flesh in his obdurate heart.”

I have often been utterly astonished, since I came to the north, to find persons who could speak of the singing among slaves as evidence of their contentment and happiness. It is impossible to conceive of a greater mistake. Slaves sing most when they are most unhappy. The songs of the slave represent the sorrows of his heart; and he is relieved by them only as an aching heart is relieved by its tears. At least, such is my experience. I have often sung to drown my sorrow, but seldom to express my happiness. Crying for joy and singing for joy were alike uncommon to me while in the jaws of slavery. The singing of a man cast away upon a desolate island might be as appropriately considered as evidence of contentment and happiness as the singing of a slave; the songs of the one and of the other are prompted by the same emotion.

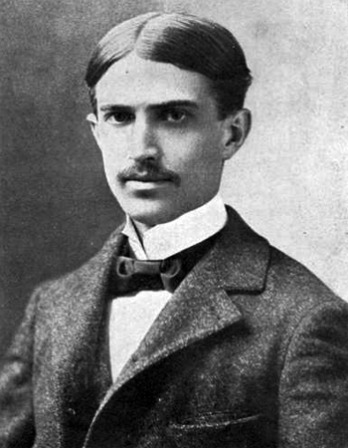

From Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass. At the age of seven or eight, Frederick Bailey was sent away from Wye House to be a servant in Baltimore, where the mistress of the household defied law to teach him how to read. After several years back at the plantation, Douglass attempted to escape in 1836 but was caught. Two years later he successfully fled to New York City, then settled in New Bedford, Massachusetts, where he changed his last name to Douglass to avoid detection. He published his autobiography in 1845.

Back to Issue