Music today is nothing more than the art of performing difficult pieces.

—Voltaire, 1759Battle of the Bands

Ivan Turgenev in the village tavern.

Few of my readers have probably had an opportunity of getting a good view of any village taverns, but we sportsmen go everywhere.

They are constructed on an exceedingly simple plan. They usually consist of a dark outer shed, and an inner room with a chimney, divided in two by a partition, behind which none of the customers have a right to go. In this partition there is a wide opening cut above a broad oak table. At this table or bar the spirits are served. Sealed-up bottles of various sizes stand on the shelves, right opposite the opening. In the front part of the room, devoted to customers, there are benches, two or three empty barrels, and a corner table.

When I went into the Welcome Resort, a fairly large party was already assembled there.

In his usual place behind the bar, almost filling up the entire opening in the partition, stood Nikolai Ivanitch in a striped print shirt; with a lazy smile on his full face, he poured out with his plump white hand two glasses of spirits for the Blinkard and the Gabbler as they came in. Behind him, in a corner near the window, could be seen his sharp-eyed wife. In the middle of the room was standing Yashka the Turk, a thin, graceful fellow of twenty-three, dressed in a long skirted coat of blue nankeen. Near him stood a man of about forty, with broad shoulders and broad jaws, with a low forehead, narrow Tartar eyes, a short flat nose, a square chin, and shining black hair coarse as bristles. He was called the Wild Master. Right opposite him, on a bench under the holy pictures, was sitting Yashka’s rival, the booth keeper from Zhizdry. He was a short, stoutly built man about thirty, pockmarked and curly headed, with a blunt, turned-up nose, lively brown eyes, and a scanty beard.

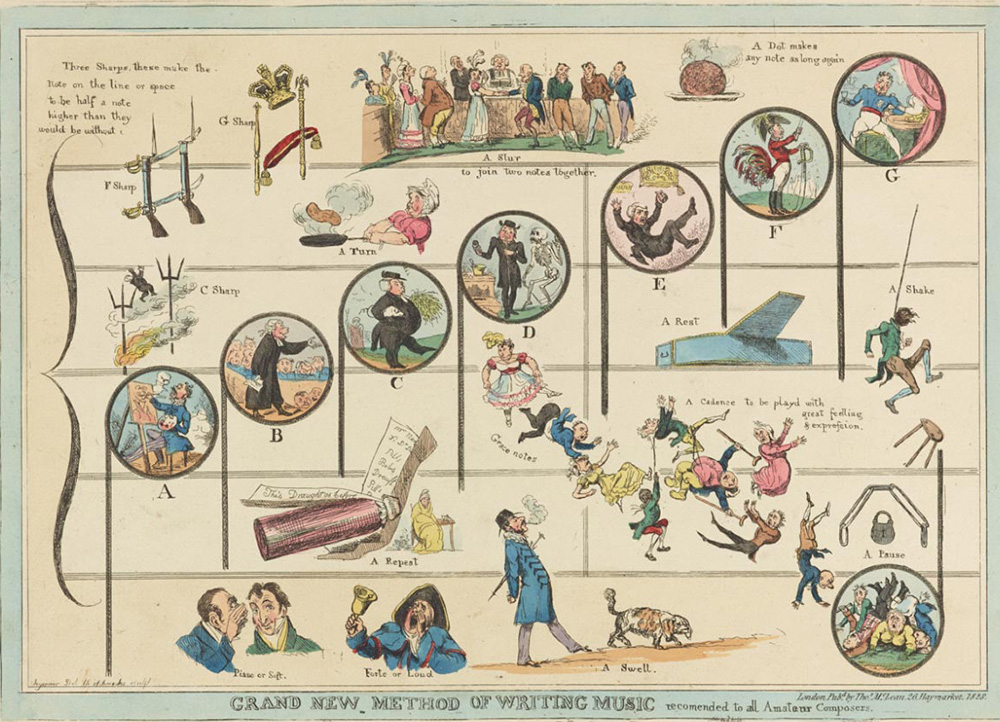

Grand New Method of Writing Music Recommended to All Amateur Composers, by Robert Seymour, 1828. © Philadelphia Museum of Art, William H. Helfand Collection, 2012.

My entrance, I could see, was at first somewhat disconcerting to Nikolai Ivanitch’s customers; but observing that he greeted me as a friend, they were reassured, and took no more notice of me. I asked for some beer and sat down in the corner, near a peasant in a ragged smock.

“Well, well,” piped the Gabbler, suddenly draining a glass of spirits at one gulp, accompanying his exclamation with strange gesticulations, without which he seemed unable to utter a single word. “What are we waiting for? If we’re going to begin, then begin. Hey, Yashka?”

“Begin, begin,” chimed in Nikolai Ivanitch approvingly.

“Let’s begin, by all means,” observed the booth keeper coolly, with a self-confident smile. “I’m ready.”

“And I’m ready,” Yakov pronounced in a voice thrilled with excitement.

The booth keeper pulled down his girdle and cleared his throat. “But who’s to begin?” he inquired in a slightly changed voice.

“You, you, booth keeper,” stammered the Gabbler. “You, to be sure, brother.”

The Wild Master looked at him from under his brows. The Gabbler gave a faint squeak, in confusion looked away at the ceiling, twitched his shoulder, and said no more.

“Begin,” the Wild Master said, with a nod to the booth keeper.

“What song am I to sing?” asked the booth keeper, beginning to be nervous.

“What you choose,” answered the Blinkard. “Sing what you think best.”

And so the booth keeper stepped forward and, half shutting his eyes, began singing in high falsetto. He had a fairly sweet and pleasant voice, though rather hoarse. He played with his voice like a woodlark, twisting and turning it in incessant roulades and trills up and down the scale. His modulations were at times rather bold, at times rather comical. He seemed to feel that he was among really musical people, and therefore was exerting himself to do his best. The booth keeper sang for a long while without evoking much enthusiasm in his audience; but at last, after one particularly bold flourish, which set even the Wild Master smiling, the Gabbler could not refrain from a shout of delight. Everyone was roused. The Gabbler and the Blinkard began joining in in an undertone, and exclaiming, “Bravely done!…Take it, you rogue!…Sing it out, you serpent!” and so on. Emboldened by the signs of general approbation, the booth keeper went off in a whirl of flourishes, and began to round off such trills, to turn such shakes off his tongue, and to make such furious play with his throat that when at last, pale, exhausted, and bathed in hot perspiration, he uttered the last dying note, his whole body flung back, a general united shout greeted him in a violent outburst.

“Well, brother, you’ve given us a treat!” bawled the Gabbler, not releasing the exhausted booth keeper from his embraces. “You’ve given us a treat, there’s no denying! You’ve won, brother, you’ve won! I congratulate you—the quart’s yours! Yashka’s miles behind you.”

“You sing beautifully, brother, beautifully,” Nikolai Ivanitch observed caressingly. “And now it’s your turn, Yashka. Mind, now, don’t be afraid. We shall see who’s who. We shall see. The booth keeper sings beautifully, though, ’pon my soul, he does.”

“Yakov, begin!” said the Wild Master.

Yakov took himself by his throat: “Well, really, brothers…something…Hmm, I don’t know, on my word, what…”

“Come, that’s enough. Don’t be timid. For shame!…why go back?…Sing the best you can, by God’s gift.”

The Enraged Musician, by William Hogarth, 1741. Courtesy of the National Gallery of Art, Washington, Rosenwald Collection.

Yakov was silent for a minute; he glanced around and covered his face with his hand. All had their eyes simply fastened on him, especially the booth keeper, on whose face a faint, involuntary uneasiness could be seen through his habitual expression of self-confidence and the triumph of his success. When at last Yakov uncovered his face, it was pale as a dead man’s. He gave a deep sigh and began to sing…The first sound of his voice was faint and unequal, and seemed not to come from his chest but to be wafted from somewhere far off, as though it had floated by chance into the room. A strange effect was produced on all of us by this trembling, resonant note. We glanced at one another, and Nikolai Ivanitch’s wife seemed to draw herself up. This first note was followed by another, bolder and prolonged, but still obviously quivering, like a harp string when suddenly struck by a stray finger it throbs in a last, swiftly dying tremble; the second was followed by a third, and gradually gaining fire and breadth, the strains swelled into a pathetic melody. “Not one little path ran into the field,” he sang, and sweet and mournful it was in our ears. I have seldom, I must confess, heard a voice like it; it was slightly hoarse, and not perfectly true; there was even something morbid about it at first; but it had genuine depth of passion, and youth and sweetness and a sort of fascinating, careless, pathetic melancholy. A spirit of truth and fire, a Russian spirit, was sounding and breathing in that voice, and it seemed to go straight to your heart, to go straight to all that was Russian in it. The song swelled and flowed. Yakov was clearly carried away by enthusiasm. He was not timid now; he surrendered himself wholly to the rapture of his art; his voice no longer trembled; it quivered, but with the scarce perceptible inward quiver of passion, which pierces like an arrow to the very soul of the listeners, and he steadily gained strength and firmness and breadth. He sang, utterly forgetful of his rival and all of us. He seemed supported, as a bold swimmer by the waves, by our silent, passionate sympathy. He sang, and in every sound of his voice, one seemed to feel something dear and akin to us, something of breadth and space, as though the familiar steppes were unfolding before our eyes and stretching away into endless distance. I felt the tears gathering in my bosom and rising to my eyes; suddenly I was struck by dull, smothered sobs…I looked around—the innkeeper’s wife was weeping, her bosom pressed close to the window. Yakov threw a quick glance at her, and he sang more sweetly, more melodiously than ever. Nikolai Ivanitch looked down; the Blinkard turned away; the Gabbler, quite touched, stood, his gaping mouth stupidly open; the humble peasant was sobbing softly in the corner and shaking his head with a plaintive murmur; and on the iron visage of the Wild Master, from under his overhanging brows there slowly rolled a heavy tear; the booth keeper raised his clenched fist to his brow and did not stir…I don’t know how the general emotion would have ended if Yakov had not suddenly come to a full stop on a high, exceptionally shrill note—as though his voice had broken. No one called out, or even stirred. Everyone seemed to be waiting to see whether he was not going to sing more; but he opened his eyes as though wondering at our silence, looked around at all of us with a face of inquiry, and saw that the victory was his…

“Yashka,” said the Wild Master, laying his hand on his shoulder, and he could say no more.

We all stood, as it were, petrified. The booth keeper softly rose and went up to Yakov.

“You…yours…you’ve won,” he articulated at last with an effort and rushed out of the room.

Ivan Turgenev

From Sketches from a Hunter’s Album. Originally published in the Russian journal The Contemporary between 1847 and 1851, these sketches—the first of Turgenev’s major writings to gain lasting recognition—portrayed Russian country life prior to the emancipation of serfs in 1861. After they appeared as a book in 1852, Turgenev was arrested and sentenced to eighteen months’ enforced residence at his family’s rural estate. Sherwood Anderson called the work “the sweetest thing in all literature.”