While making applications to the different medical colleges of Philadelphia for admission as a regular student, I enlisted the services of my friends in the search for an alma mater. The interviews with the various professors, though disappointing, were often amusing.

May 27

Called on Dr. Jackson (one of the oldest professors in Philadelphia), a small, bright-faced, gray-haired man, who looked up from his newspaper and saluted me with, “Well, what is it? What do you want?” I told him I wanted to study medicine. He began to laugh, and asked me why. Then I detailed my plans. He became interested, said he would not give me an answer then—that there were great difficulties, but he did not know that they were insurmountable; he would let me know on Monday. I came home with a lighter heart, though I can hardly say hope. On Monday, Dr. Jackson said he had done his best for me, but the professors were all opposed to my entrance. Dr. Horner advised me to try the Filbert Street and Franklin schools. A professor of Jefferson College thought it would be impossible to study there and advised the New England schools.

June 2

Felt gloomy as thunder, trudging round to Dr. Darrach. He is the most noncommittal man I ever saw. I harangued him, and he sat a full five minutes without a word. I asked at last if he could give me any encouragement.

“The subject is a novel one, madam, I have nothing to say either for or against it; you have awakened trains of thought upon which my mind is taking action, but I cannot express my opinion to you either one way or another.”

“Your opinion, I fear, is unfavorable.”

“I did not say so. I beg you, madam, distinctly to understand that I express no opinion one way or another; the way in which my mind acts in this matter I do not feel at liberty to unfold.”

“Shall I call on the other professors of your college?”

“I cannot take the responsibility of advising you to pursue such a course.”

“Can you not grant me admittance to your lectures, as you do not feel unfavorable to my scheme?”

“I have said no such thing; whether favorable or unfavorable, I have not expressed any opinion, and I beg leave to state clearly that the operation of my mind in regard to this matter I do not feel at liberty to unfold.” I got up in despair, leaving his mind to take action on the subject at his leisure.

The fear of successful rivalry which at that time often existed in the medical mind was expressed by the dean of one of the smaller schools, who frankly replied to the application, “You cannot expect us to furnish you with a stick to break our heads with,” so revolutionary seemed the attempt of a woman to leave a subordinate position and seek to obtain a complete medical education. A similarly mistaken notion of the rapid practical success which would attend a lady doctor was shown later by one of the professors of my medical college, who was desirous of entering into partnership with me on condition of sharing profits over five thousand dollars on my first year’s practice.

During these fruitless efforts my kindly Quaker adviser, whose private lectures I attended, said to me, “Elizabeth, it is of no use trying. You cannot gain admission to these schools. You must go to Paris and don masculine attire to gain the necessary knowledge.” Curiously enough, this suggestion of disguise made by good Dr. Warrington was also given to me by Dr. Pankhurst, the professor of surgery in the largest college in Philadelphia. He thoroughly approved of a woman’s gaining complete medical knowledge, told me that although my public entrance into the classes was out of the question, if I would assume masculine attire and enter the college, he could entirely rely on two or three of his students to whom he should communicate my disguise, who would watch the class and give me timely notice to withdraw should my disguise be suspected.

But neither the advice to go to Paris nor the suggestion of disguise tempted me for a moment. It was to my mind a moral crusade on which I had entered, a course of justice and common sense, and it must be pursued in the light of day, and with public sanction, in order to accomplish its end.

How perceptions and humors travel through the body, woodcut from René Descartes’ Treatise of Man, 1664.

The following letter to Mrs. Willard of Troy, the well-known educationalist, describes the difficulties through which the young student had to walk warily:

Philadelphia, May 24

I cannot refrain from expressing my obligations to you for directing me to the excellent Dr. Warrington. He has allowed me to visit his patients, attend his lectures, and make use of his library, and has spoken to more than one medical friend concerning my wishes; but with deep regret I am obliged to say that all the information hitherto obtained serves to show me the impossibility of accomplishing my purpose in America. I find myself rigidly excluded from the regular college routine, and there is no thorough course of lectures that can supply its place. The general sentiment of the physicians is strongly opposed to a woman’s intruding herself into the profession; consequently, it would be perhaps impossible to obtain private instruction, but if that were possible, the enormous expense would render it impracticable, and where the feelings of the profession are strongly enlisted against such a scheme, the museums, libraries, hospitals, and all similar aids would be closed against me. In view of these and numerous other difficulties, Dr. Warrington is discouraged and joins with his medical brethren in advising me to give up the scheme. But a strong idea, long-cherished till it has taken deep root in the soul and become an all-absorbing duty, cannot thus be laid aside. I must accomplish my end. I consider it the noblest and most useful path that I can tread, and, if one country rejects me, I will go to another.

Through Dr. Warrington and other sources, I am informed that my plan can be carried out in Paris, though the free government lectures delivered by the faculty are confined to men, and a diploma is strictly denied to a woman—even when (as in one instance, it is said) she has gone through the course in male attire. Yet every year, thorough courses of lectures are delivered by able physicians on every branch of medical knowledge, to which I should be admitted without hesitation and treated with becoming respect. The true place for study, then, seems open to me; but here again some friendly physicians raise stronger objections than ever. “You, a young, unmarried lady,” they say, “go to Paris, that city of fearful immorality, where every feeling will be outraged and insult attend you at every step—where vice is the natural atmosphere, and no young man can breathe it without being contaminated! Impossible. You are lost if you go!”

After a short, refreshing trip with my family to the seaside, the search was again renewed in Philadelphia. But applications made for admission to the medical schools both of Philadelphia and of New York were met with similarly unsuccessful results.

I therefore obtained a complete list of all the smaller schools of the northern states, “country schools,” as they were called. I examined their prospectuses and quite at a venture sent in applications for admission to twelve of the most promising institutions, where full courses of instruction were given under able professors. The result was awaited with much anxiety, as the time for the commencement of the winter sessions was rapidly approaching. No answer came for some time. At last, to my immense relief (though not surprise, for failure never seemed possible), I received the following letter from the medical department of a small university town in the western part of the state of New York:

Geneva, October 20

To Elizabeth Blackwell,

I am instructed by the faculty of the medical department of Geneva University to acknowledge receipt of yours of application. A quorum of the faculty assembled last evening for the first time during the session, and it was thought important to submit your proposal to the class (of students), who have had a meeting this day and acted entirely on their own behalf, without any interference on the part of the faculty. I send you the result of their deliberations—and need only add that there are no fears but that you can, by judicious management, not only disarm criticism, but elevate yourself without detracting in the least from the dignity of the profession.

Wishing you success in your undertaking, which some may deem bold in the present state of society, I subscribe myself,

Yours respectfully,

Charles A. Lee, Dean of the Faculty

This letter enclosed the following unique and manly letter, which I afterward copied on parchment, and esteem one of my most valued possessions:

At a meeting of the entire medical class of Geneva Medical College, held this day, October 20, 1847, the following resolutions were unanimously adopted:

1. Resolved—That one of the radical principles of a republican government is the universal education of both sexes; that to every branch of scientific education the door should be open equally to all; that the application of Elizabeth Blackwell to become a member of our class meets our entire approbation; and in extending our unanimous invitation, we pledge ourselves that no conduct of ours shall cause her to regret her attendance at this institution.

2. Resolved—That a copy of these proceedings be signed by the chairman and transmitted to Elizabeth Blackwell.

—T. J. Stration, Chairman

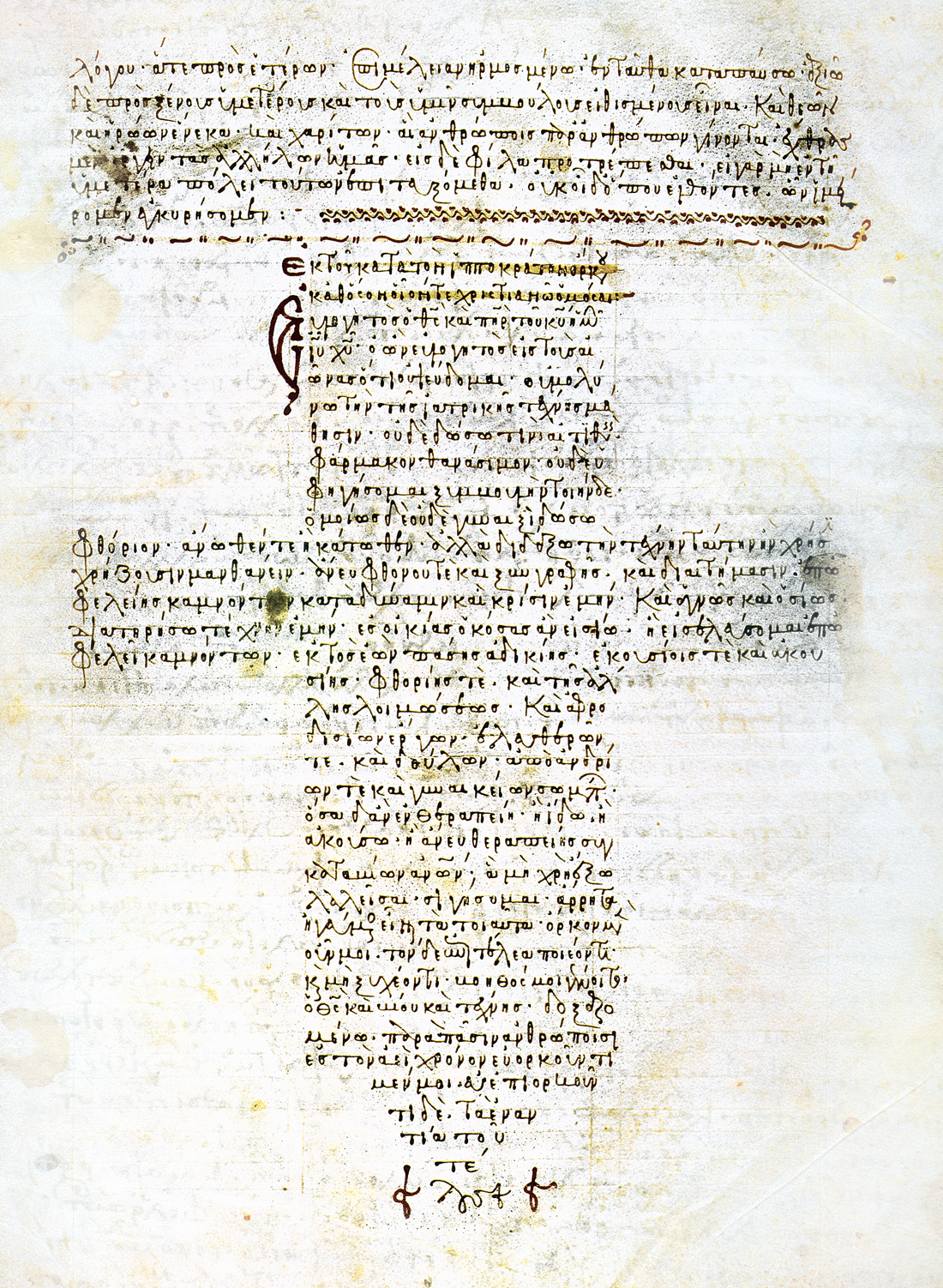

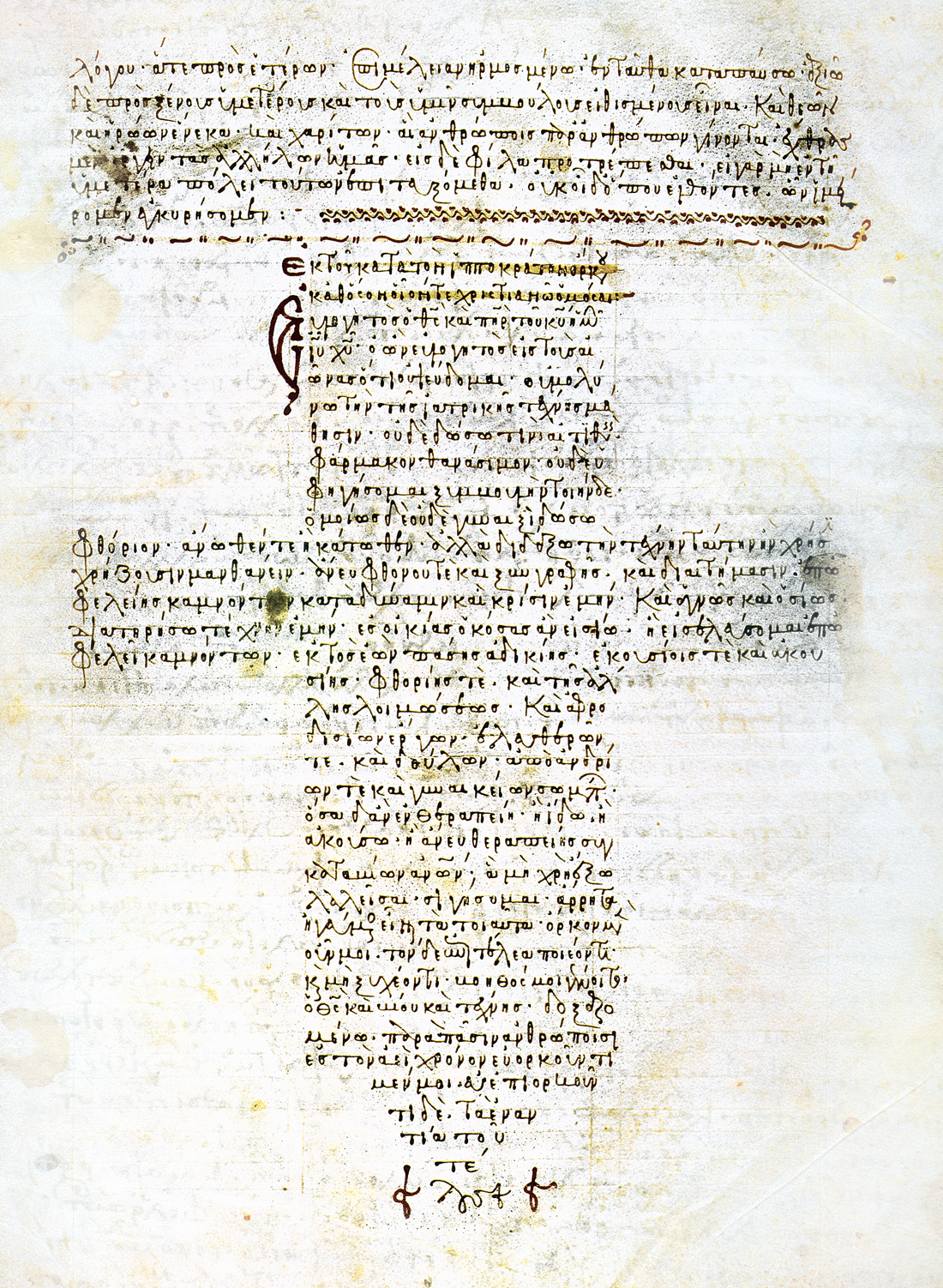

The Hippocratic Oath, Byzantine manuscript, twelfth century

With an immense sigh of relief and aspiration of profound gratitude to Providence, I instantly accepted the invitation, and prepared for the journey to western New York.

Leaving Philadelphia on November 4, I hastened through New York, traveled all night, and reached the little town of Geneva at 11 P.M. on November 6.

The next day, after a refreshing sleep, I sallied forth for an interview with the dean of the college, enjoying the view of the beautiful lake on which Geneva is situated, notwithstanding the cold, drizzling, windy day. After an interview with the authorities of the college I was duly inscribed on the list as student No. 130 in the medical department of the Geneva University.

From Pioneer Work in Opening the Medical Profession to Women. Blackwell graduated from the Geneva Medical College at the top of her class in 1849. She helped form the New York Infirmary for Women and Children in 1857, trained nurses during the Civil War, and after consulting Florence Nightingale, opened the Woman’s Medical College in 1868. She died in her native England in 1910 at the age of eighty-nine.

Back to Issue